The Wizard of Uz: Job’s Theology

by David P. Gontar (December 2020)

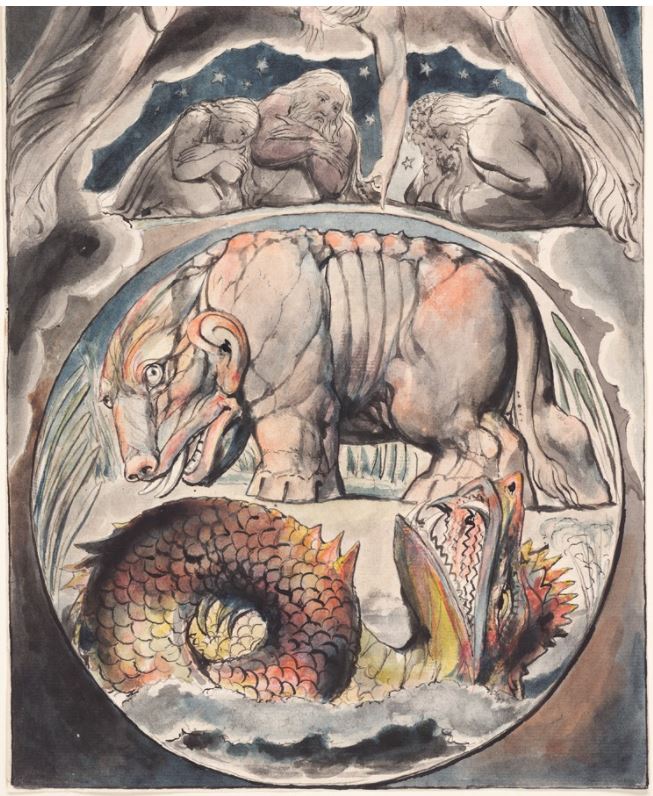

Behold Now Behemoth, Which I Made With Thee (The Book of Job), William Blake, 1821

I form the light, and create darkness: I make peace, and create evil: I the Lord do all these things. —Isaiah 45:7

At a moment when many are turning to their faith to comprehend a gathering gloom, it may be apropos to glance at the Old Testament’s Book of Job. There in the ancient “Land of Uz” presides an impulsive and unruly spirit, far more unsettled than the compassionate shepherd (e.g., Psalm 23) to whom we have grown accustomed. We recognize our present Savior as the fountainhead of caritas, brotherhood, and moral strictures, the object of praise and heartfelt petitions. But because our Redeemer liveth as largely affirmative, He is predominantly homogeneous. The God featured in the Book of Job is more variegated, an impassioned, conflicted Zauberer, celestial and chthonic, capricious and given to pranks. Usually the Book of Job is consulted to draw the fangs of the “problem of evil,” a philosophical effort to explain how it is that our world, supervised by a strong and caring Agency, should be filled with pain and sorrows: Like Job we must suffer, but in the end we meet our Maker and prosper. QED. The divine character and personality per se are not taken up in that Biblical application. When we do finally read its verses we are startled to see that the God of Job seems to dwell nearly as close to vice as to virtue. For popular theologians the precise make-up of God in Job is not of great interest. Their theodicies recycle the same intellectual gambits aimed at defeating the Gnostic heresy deeming creation itself evil. Yet the narrative of Job is fundamentally a vivid personal drama in which our Master lives, moves, and often exhibits himself in abrasive act and speech. Job’s supreme being is no humdrum hero but a restless prince whose manifold foibles make our interactions with Him as fraught with risk as with rewards. This gives new and powerful sense to the locution “the fear of the Lord.” In what follows we will briefly sojourn with the God who stars in the Book of Job and ruminate upon His idiosyncrasies and indiscretions. Detailed treatment of the dialogue of Job and his three friends is set aside to focus on sacred character.

1. The Prologue

Following the acknowledgement of Job as a servant of the Lord, flawless in all respects (1:1), we find ourselves beyond the firmament where God holds court. [Note that the first description of Job as “perfect” comes from the scriptural writer and is echoed by God (1:8; 2:3). No doubt is left about this.]

Here is the first of two often-neglected verses. Let us take it as seriously as it was intended.

Now there was a day when the sons of God came to present themselves before the Lord, and Satan came also among them. And the Lord said unto Satan, Whence comest thou? Then Satan answered the Lord, and said, From going to and fro in the earth, and from walking up and down in it. And the Lord said unto Satan, Hast thou considered my servant Job, that there is none like him in the earth, a perfect and an upright man, one that feareth God, and escheweth evil? Then Satan answered the Lord, and said, Doth Job fear God for nought? Hast not thou made an hedge about him, and about his house, and about all that he hath on every side? Thou hast blessed the work of his hands, and his substance is increased in the land. But put forth thine hand now, and touch all that he hath, and he will curse thee to thy face. And the Lord said unto Satan, Behold, all that he hath is in thy power; only upon himself put not forth thy hand. So Satan went forth from the presence of the Lord. Job (1:6-12)

2. Commentary

Here Satan is evidently one of the “sons of God” also mentioned in Genesis 6:2. Even though he is technically an Adversary, he appears at a social gathering up Yonder. He is queried as to his recent whereabouts, implying he is not confined to Hell. In fact, Satan is something of a foot-loose dandy, having just returned from an earthly or earthy vacation where he observed the qualities of people. (Cp. Antony and Cleopatra, 1.1.55) There is no indication that Satan crashes the party. Rather we witness a warm exchange of father and son in which the devil, as kin to God Himself, is not anathematized. On the contrary. The two strike up an intimate chat in which God boasts to his son, Satan, of Job’s probity and fidelity. It seems that God is inordinately proud of Job’s devotion and mentions no rivals. Satan then cleverly turns the tables on his father by teasingly observing that Job’s obedience is nothing but a function of favors and blessings. Remove those gratuities and your “perfect” servant will curse you to your face, says he. (Job 1:11) God accepts Satan’s implicit wager or experiment, giving him actual authority to oppress Job in every way but physical outrage. Here God stumbles into a trap, for even if Job should prove loyal to Him during the proposed cruelties, Satan will have prevailed in having ruined this noble man and stolen his bliss. Do we care? Ironically, this wager is designed to measure Job’s fidelity—with Job picking up the tab.

Put in the balance we behold:

- God’s pride prompts him to boast of Job’s perfection;

- God does not resist Satan’s temptation

- Rather than content himself with what he knows full well, God enters a wager with his son, betting on Job;

- The price of the wager will be borne by the hapless mortal

- God’s grant of nearly complete freedom to Satan to ruin Job is not passive but part of a lethal conspiracy against his own erstwhile servant, a perfidious blow against a patient and helpless man admitted by God to be flawless in belief and behavior. Note the grant is not merely permissive, it empowers Satan. God’s role in harming Job is thus altogether causative

- The wager flies in the face of God’s omniscience inasmuch as we presume he knows full well that Job will remain steadfast. The painful experiment, playing with Job’s security and well-deserved satisfaction, is completely careless and unnecessary

- Finally, the bond of God and Satan is telling. Though the former favors Job’s moral worth as a good bet, He does Job no favors as a guardian. In fact, what we see is that God, the very quintessence of goodness, in assailing his most outstanding follower, sanctions and performs evil. Whose side is He on? This should come as no surprise to readers of Isaiah 45:7. God is seemingly more concerned to triumph over his son Satan than to shield the sinless mortal from harm. Though he cherishes the innocent man Job, God, like a hyperactive child with a fragile toy, is willing to team up with Satan to hurl this man to the wall just to see if he breaks.

There follow a series of blows which rain upon Job with a bizarre fury.

- His servants are slain by the Sabeans. (1:18)

- A “fire from God” (or holocaust) incinerates his flocks and other servants (1:16) We would see such an event today as “genocide.”

- The Chaldeans kill off Job’s camels and murder the remaining servants by the sword. (1:17)

- Job’s remaining offspring are executed by a “great wind from the wilderness.” (1:19)

Somehow Job himself survives this unspeakable onslaught. There is then convened a second summit meeting of God and Satan. This time God notes that “still [Job] holdeth fast his integrity, though thou movedst me against him, to destroy him without cause.” (2:3) This is an astonishing statement against interest. It confirms that God does indeed yield to Satan’s provocation, that He takes an active part in the undoing of Job (e.g., “fire from God”), and that there is nothing in this man meriting such gross mistreatment. When Satan lets on that Job’s bodily health has been preserved, implying that undermining it would bring forth blasphemy, God loses not a moment in consenting to Job’s debility: “And the Lord said unto Satan, Behold, he is in thy hand, but save his life.” (2.6) “So went Satan forth from the presence of the Lord, and smote Job with sore boils from the sole of his foot unto his crown.” (2.7) At this point we detect comical overtones in the unfolding tragedy, which evinces the three-part structure of a common joke.

Now languishing on a heap of ashes, Job ignores his wife’s choice imprecation to “curse God and die.” “But he said unto her, thou speakest as one of the foolish women speaketh. What? Shall we receive good at the hand of God, and shall we not receive evil?” Here is a fine specimen of Job’s sturdy but useless realism. And the biblical scribe adds, “in all this did not Job sin with his lips.” (2:10) Nevertheless, neither God nor the three friends of Job are content. His guests, who are supposed to console him, cannot tolerate his lamentations, which appear premised on an unshakable sense of his own inherent righteousness. Bodily injuries now compound his losses. Surely there must be a secret sin in Job’s bosom that attracts the coals heaped on his head, and it is precisely this supposition Job strenuously denies. Here lies the moral crux, for: “If I justify myself, mine own mouth shall condemn me: if I say I am perfect, it shall also prove me perverse,” (9:20) a deep insight that captures the poignance of the human predicament. Job’s hunch about who is behind his miseries tallies with what we ourselves have seen.

Now there is one more overriding consideration to take into account in order to appreciate the monstrous lot of Job and the abominable character of his Lord. Throughout the entire Book of Job, beginning with the debate between Satan and his Father and concluding with Elihu’s speech (beginning in Chapter 32), God’s harangue (beginning in Chapter 38), and Job’s penitent reconciliation and restoration, we find zero mention from God concerning the vendetta against Job conceived and implemented by Him and Satan. Even after the restoration (42:10-17) God never discloses what generated Job’s fate. And as we make our way through the competing arguments of Job and his three accusers, we find him supposing that his misery is indeed the handiwork of God, though there be no confirmation of this fact. It is plain that this beatific reticence is meant to invoke the ignorance of the human condition. As we shall see, even though God wins his fiendish wager, Job’s complaint is deeply resented by God, who grumbles on and on over Job’s inescapable doubts and suspicions. The fact is that God neglects to explain to Job what has happened to him because doing so would surely cause Him to lose the respect of Job altogether. God would in effect become Satan—as he appears. Hence Job knows and knows not, and in his concluding allegiance and restoration he becomes resigned and satisfied—or exhausted. But it is a shallow satisfaction, ever shrouded in discreet darkness. He is never granted his redeeming moment of insight.

3. God’s Attorney

Sandwiched discreetly between the dialogue with Job’s three friends and the direct testimony of God Himself, we find young Elihu, who serves as Counsel to the Lord, arguing on behalf of the Defendant, God. (Chapter 32 ff.) Elihu submits:

“[F]ar be it from God, that he should do wickedness; and from the Almighty that he should commit iniquity.” (34:10) “Yea, surely God will not do wickedly, neither will the Almighty pervert judgment.” (34:12) Protesting a tad too much, perhaps? In fairness to Attorney Elihu it must be understood that there is no evidence that he is privy to the actual facts of his client’s conduct. What is asserted in this instance is presented as self-evident when it is truly false. If we accept Elihu’s dicta, Job’s accusations against his Maker are of course unfair and possibly sanctionable. But based on what has actually occurred, what we have seen of God’s venom and guile, Elihu’s brief must be disregarded. The witnesses needed to prove his point are not in court, and even if they were, it would be unavailing. It is actually painful to listen to this man, heedless of the key facts yet insistent when he avouches “God is greater than man.” (33:12) “Why dost thou strive against him?” (33:13) Rising into a crescendo of fantasy he joins the three friends in seeking to make Job the fall guy in the story. Elihu’s discourse is a classic instance of bearing false witness against one’s neighbor.

Job hath spoken without knowledge, and his words were without wisdom. My desire is that Job may be tried unto the end because of his answers for wicked men. For he addeth rebellion unto his sin, he clappeth his hands among us, and multiplieth his words against God. (34:35-37)

What is this fellow talking about? Rebellion? Words against God? Wait a minute. Job has lost all one possibly could, his home, his possessions, his livelihood, even ten children. He writhes upon the ground (cp. King Richard II (3.2.151)), body lacerated with horrid sores as he endures the sadistic needling of his “friends.” Tragically, neither long suffering Job nor Elihu is aware of the operative facts. Elihu’s description of this miserable man is no better than a cruel caricature. And Job isn’t the defendant here. He is the complainant. How could any penalty be greater than what he now bears?

4. God’s Expostulation

Following the unfortunate address of Elihu, God himself now responds to Job out of the whirlwind, putting us in mind of the “great wind” which collapsed the house on Job’s sons. (1:19) Here the full brunt of His power and majesty descends upon the helpless Job, tarnishing still more God’s moral profile. In overwhelming stanzas which outdo anything in world literature, God chastises Job for daring to take issue with his Maker, aligning with a well-established trope in scripture. (Isaiah 45:9; Romans 9:20-23; 1 Corinthians 10:22; Daniel 4:35; Job 9:12, and 33:13) Confronted in Measure for Measure by the hypocritical ruler Angelo, Isabella cries: “Could great men thunder as Jove himself does, Jove would never be quiet, for every pelting officer would use his heaven for thunder, nothing but thunder.” (Measure for Measure, 2.2.113-116) Such puffery practiced by God makes him smaller, not enlarged. One is tempted to retort, “Does the potter do harm to his own best pot?” If this is warranted then God must have been mistaken when he praised his servant Job as “perfect.” But God has already told us that the excoriation of Job was “without cause.” He begins:

Who is this that darkeneth counsel by words without knowledge? Gird up now thy loins like a man for I will demand of thee, and answer thou me. Where wast thou when I laid the foundations of the earth? Declare if thou hast understanding. Who hath laid the measures thereof, if thou knowest? or who hath stretched the line upon it? Whereupon are the foundations thereof fastened? Or who laid the corner stone thereof; When the morning stars sang together, and all the sons of God shouted for joy? (38:1-7)

Such stentorian tones are all the more unseemly in the context of divine duplicity. It is indeed thunder, nothing but thunder.

Job might well have responded in kind, “Where wast thou, O, Lord, when the fire of God descended upon mine own estate, when every one of my children were slaughtered and my livelihood removed as by an earthquake? Had’st thou eyes to see the devastation of thy servant Job?” God’s discourse is largely designed to denigrate Job’s position relative to his own station and deny to him the right to judge or even inquire into the reason or source of his losses. We search in vain to find admission or denial by God of his role in Job’s undoing. The issue never arises. Consider the relative positions of these two interlocutors. One is the King of the Universe with heavy boot on someone’s neck, the other an impoverished victim grey with ash, what is left of him covered with blisters. One roars out of the whirlwind, the other barely has breath to weep. And well do we know the simple unvarnished answer to those impertinent and unasked questions: God was busy entertaining his sons at a social function, and entered into a wager with his wayward Satan, the outcome of which could hardly have been opaque to omniscience. It is easy enough for God to challenge Job’s right to query the chief authority of the universe concerning his bad luck, easy, that is, so long as that original wager is kept under wraps. God takes advantage of Job’s weaknesses and lack of information to cow him with bluster and force him to apologize. It is one thing to step on an ant, though, another to annihilate it with a Howitzer. Isn’t this just bullying? But the deepest cut of all is the sheer dishonesty of God’s cross examination, based as it is on the proscribed suppression of inculpatory evidence. One can hardly avoid thinking of Job’s God as one with a yen for schadenfreude.

5. The Restoration

At last in response to the terrors of God’s presence, Job crumbles and abandons his doubts. “I have heard of thee by the hearing of the ear: but now mine eye seeth thee. Wherefore I abhor myself, and repent in dust and ashes.” (42:5-6) And though no more is said by the parties, we learn at the penultimate moment that we have not been in error, the worst did come to pass: for Job received consolation from his brethren “over all the evil that the Lord had brought upon him.” (42:11) The story comes to a dubious conclusion with God’s apparently complete restitution of Job to his former state of health and prosperity, including ten new children to replace those He whacked. We read: “After this lived Job an hundred and forty years, and saw his sons, and his son’s sons, even four generations. So Job died, being old and full of days.” (42:16-17) Given this tumultuous history, we might venture to ask whether the restoration was satisfactory and equitable given the nature of the damages. For the memory of this entire episode cannot be erased, and we must suppose that there were times during those 140 latter years when Job let a tear or two fall over the stresses he had battled. Today the doctors would have no problem diagnosing PTSD. And though it’s pleasant to learn of his new family (and apparently reconciled wife, busy once more), children certainly are not fungible commodities, and though new offspring may be lovely they could never in fact entirely replace those which had been sacrificed, despite the touching allure of “Jemima, Kezia and Kerenhappuch.” (42:14)

6. Conclusions

- The Book of Job depicts a deeply flawed deity with palpable ties to Evil who commits grave wrongs against Job and his family. He then engages in a cover-up operation designed to camouflage his misdeeds.

- The most serious of His offenses is not the physical and mental brutalities themselves but the willful refusal to concede His role in Job’s downfall.

- Those who claim that Job’s harassment is justified by his humbling and restoration fail to take into account the extent of that mistreatment and the sheer mendacity of God’s failure to admit the awful truth.

- With all due respect, those who teach the Book of Job in churches and seminaries would do well to consider that “the fear of the Lord” is not always a desirable commodity, especially when theophobia is brought about by divine flaws of character. What is this God but the proverbial loose cannon on deck?

- An argument could be made that the events set forth in the Book of Job represent a significant victory for Satan.

- Viewed in dialectical terms, orthodox theology wavers between a single deity containing good and evil aspects within himself (as in Isaiah 45:7) and two discrete figures, one exclusively good, the other entirely malicious. These alternatives are not stable, but remain subject to anthropomorphic permutations and combinations, as we have seen here and in the history of Gnosticism, Catharism, etc. The logic of such transmutations was best exhibited by FH Bradley in his long-forgotten masterpiece, Appearance and Reality in 1893.

- Could it be that the feared “pandemic” is actually the “pandemonic?” The bizarre conviction that we today are somehow wiser than those who have gone before us remains the most striking evidence of brazen folly.

Epilogue

“They say that miracles are past, and we have our philosophical persons to make modern and familiar things supernatural and causeless. Hence it is that we make trifles of terrors, ensconcing ourselves into seeming knowledge when we should submit ourselves to an unknown fear.”

***

“Are you not moved, when all the sway of earth

Shakes like a thing unfirm? O, Cicero,

I have seen tempests when the scolding winds

Have rived the knotty oaks, and I have seen

Th’ ambitious ocean swell and rage and foam

To be exalted with the threat’ning clouds;

But never till tonight, never till now,

Did I go through a tempest dropping fire.

Either there is a civil strife in heaven

Or else the world, too saucy with the gods,

Incenses them to send destruction.”

—Shakespeare

____________________

David Gontar has been writing for New English Review since 2011. Through New English Review Press he has brought out two books on Shakespeare. David is now retired, living abroad and teaching English.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast