by Ralph Berry (March 2021)

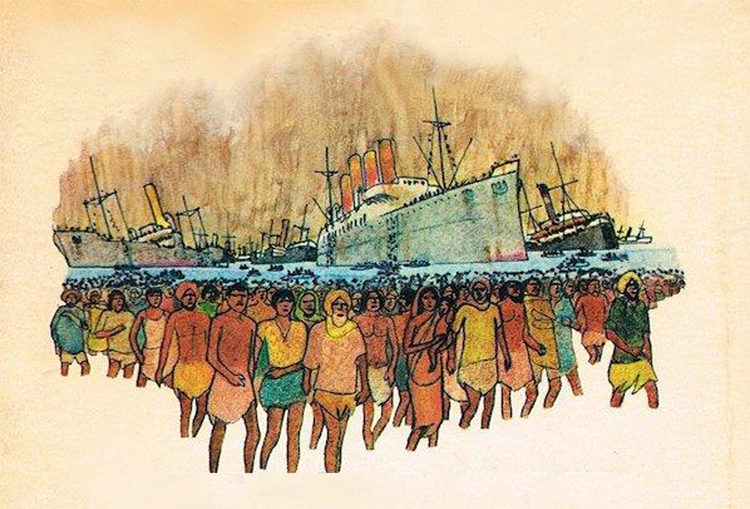

Cover art from Camp of the Saints, First Edition,1973

Jean Raspail died June 13, 2020. The Telegraph did not get round to printing an obituary till August 26th, perhaps a sign of editorial disapproval. If so, this was nothing new for Raspail’s novel Le Camp des Saints (1973). His title is taken from Revelation 20:7-9, with its prophecy that when a thousand years have passed ‘Satan shall be loosed out of his prison.’ His followers ‘shall go out to deceive the nations…And they went up on the breadth of the earth, and compassed the camp of the saints…’ That is the Authorized Version; the New English Bible has ‘seduced’ for ‘deceived’. In Raspail’s fable, a flotilla of refugees from the Indian sub-continent makes its way to the South of France, where they land and go on to advance. The French Government does not have the nerve to repel the arrivals, and eventually the West falls to the mass emigration known as ‘the grand replacement.’ With prophetic accuracy, Raspail described the invasion of the West by the Third World.

Le Camp des Saints ran into predictable criticism as a work of deranged racism. It was taken up by the Right, and Lionel Shiver saw it as ‘both prescient and alarming’ (2002). ‘Raspail was ahead of his time’ wrote William Buckley (2004). That was strictly true. After modest early sales, the book returned to the bestseller list in 2011, aided by praise from Steve Bannon. Four decades on from publication, France had realized that Raspail was on to something very big. Europe’s rulers are to some extent complicit in the West’s response (though not the Governments of Poland and Hungary), and Angela Merkel’s hubristic invitation to a million refugees was a giant step in the wrong direction. Le Camp des Saints took on the shape of a prediction, far too convincing for simple dismissal. From the day when Raspail in 1971 had observed boats coming ashore in the South of France, his nightmare vision had dominated his own mind and increasingly that of his country.

Nature has given assistance to Europe. The Liberal-Left opposition to Raspail rested politically on the EU doctrine, the free movement of peoples. This doctrine, now abandoned by Britain, is an ideal that cannot stand. What was largely a cause of political controversy a few months ago, debated for its demographic implications by Right and Left on approximately equal terms, now takes on the aspect of a huge public health issue that dominates the scene. Coronovirus is Nature’s back-stop to what many already fear, the invasion of Europe by non-European people in le grand remplacement. It is joined by non-European diseases that have their origins in Africa and Asia. There can be no real questioning of the need for Western societies to guard their borders with ever-greater vigilance and effectiveness. The great debate has tipped decisively one way and migration, both legal and illegal, will be stringently monitored. Europe will move towards being an armed and defended camp.

If Jean Raspail had struck a reverberant gong, Michel Houellebecq greatly amplified the sound. His novel Soumission was published on January 7th 2015, the day of the Charlie Hebdo shootings. It was an immediate bestseller in France, Germany and Italy, with an English edition coming out in September. The plot strikes at a primal fear, with France taken over by an Islamist party whose charismatic leader Ben Abbes wins the Presidential election of 2022. (Note the hint of Sidi Ben Abbes, the past headquarters in Algeria of the French Foreign Legion.) The names of real people figure with fictional characters in the book, and Socialist Party voters prefer him to Marie Le Pen as the lesser evil. Thereafter he brings in a relaxed Sharia law, with polygamy on the way. The French Establishment capitulates and, since only Muslims are allowed to teach at the Sorbonne, many professors change their religion to keep their jobs. Besides, polygamy holds attractions for hitherto non-Muslims. The takeover of the State is accomplished. The nation has submitted.

Fiction can advance into political life in ways forbidden to other writers. Robert Harris, a best-selling novelist, has form. In 2007 he published The Ghost, filmed by Roman Polanski as The Ghost Writer. It centres on a former British Prime Minister, widely seen as Tony Blair, and the corrupt relationship between him (and his wife) and the CIA. For the details of this claim, I refer readers to a single page 100. It is staggering. Real-life facts and issues make their way into the fiction, and seem to charge Blair with conduct that is indefensible. Harris himself has said that he expected a writ to be served on him. The writ never came. Blair (who is a lawyer) decided it was better to stay out of the courts.

Robert Harris then moved from the past to the predicted future. The theme of the Islamic advance into Europe is continued with Harris’s recent novel The Second Sleep, published in September 5, 2019. The exact date matters. Harris’s fiction is set 800 years into the future following the systemic collapse of civilization known as the Apocalypse. The nature and cause of this collapse are never explained but Harris has planted some clues into his narrative. A document from the pre-apocalypse period has survived. It is from The Society of Antiquaries, and a meeting dated March 22, 2022. A report from a member has this: ‘We have identified six possible catastrophic scenarios that fundamentally threaten the existence of our science-based way of life.’ The sixth is ‘A pandemic resistance to antibiotics.’

Harris has covered his bases well. The pandemic has now happened. You could regard this as good guessing, which is no more than epidemiologists were forecasting before Covid-19. But a more sinister prophecy comes on a single page. Fairfax, the priest, has been questioning a villager, who tells him:

‘My brothers has all been took by the army, sir, to fight the Northern Caliphate.’ Fairfax nodded encouragingly. ‘Brave lads, I‘m sure.’ That was a war that had gone on all his life—and for centuries beforehand, or so it was said—ever present but oddly distant, its occasional lulls punctuated by lurid reports of horrible atrocities that aroused a fervour of public outrage and set the whole thing off again. Mostly it involved dreary garrison duty in some isolated Yorkshire moorland outpost. But the regular punitive raids to keep the Islamist enclave in check always carried with them the risk of capture and beheading, which the government took care to publicise. (p.70)

That is one man’s guess at the future, and it is not elaborated. Harris is a novelist and will not take the stand to affirm his belief in his fiction’s prophecy. The imagery he deploys is that of late-imperialist action against native Islamic challengers, like the Mahdi in Sudan or the FLN in Algeria. But he is intelligent and well-informed enough to propose the Northern Caliphate as a serious and credible prospect in Britain’s future. This is a military as well as a religious entity. It is a religious war.

Obviously, the Northern Caliphate collapses the present Government’s ‘One Nation’ policy, which is left as an empty slogan. The foundations of the Northern Caliphate rest on the great strongholds of Birmingham and Manchester, together with the hard core of London. These are politically impregnable, owned by Labour and supported overwhelmingly by the Muslim population. That population is growing rapidly and no reduction in its Parliamentary representation is likely. The reader is left with a neuralgic question: does the Northern Caliphate exist already, in embryo?

__________________________________

Ralph Berry has spent his career in Canadian universities, ending with the University of Ottawa. After that, he took a Visiting Professorship in Kuwait University, followed by the University of Malaya. In recent years he has written for Chronicles magazine. His hinterland is Shakespeare, but not as a figure of Tudor history. Shakespeare’s works are a mirror to today’s issues and themes, through which we can better understand today’s politics.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link