We Will Not Go To Mars

by Adam Selene (July 2019)

.jpg) With All The Fucking Force, Michael Kagan, 2011

With All The Fucking Force, Michael Kagan, 2011

It is 50 years since the United States of America, in one of the defining triumphs of the American century, put men on the Moon. Yet the dozen men who set foot on the Moon between July 1969 and December 1972 remain the only humans to have done so. Only four of them are still alive.

By 1972, the public seemed over the Apollo program. Of the twenty planned missions, three were cancelled, due to budget cuts, concerns about risks that could cost lives and blemish the record, to launch Skylab as a permanent space station, and to channel resources into the Space Shuttle program.

No other nation has yet attempted the feat.

In light of this, it seems odd to give much credence to sending people to Mars.

The US Government’s Space Policy Directive 1 of 2017 committed the United States to:

Lead an innovative and sustainable program of exploration with commercial and international partners to enable human expansion across the solar system and to bring back to Earth new knowledge and opportunities. Beginning with missions beyond low-Earth orbit, the United States will lead the return of humans to the Moon for long-term exploration and utilization, followed by human missions to Mars and other destinations.

The Directive set no timeline, but Vice-President Mike Pence announced in April 2019 that the Trump administration’s policy is to “return American astronauts to the moon within five years.”

Read more in New English Review:

• From the Magical Land of Ellegoc to the First Man on the Moon

• Slavery is Wrong, How Can Abortion be Right?

• My America: A Portrait in Exile

Before the space community could digest that ambitious timeframe, President Trump, in a single 49-word tweet on 8 June, questioned the money being spent on the been-there-done-that mission to the Moon and said NASA “should be focused on the much bigger things we are doing, including Mars.”

Private sector champions of ambitious space exploration are as confused as the government about the way forward.

Elon Musk, admired for his boyish, entrepreneurial spirit, leads the private-sector developers of Mars missions. He says, “You want to wake up in the morning and think the future is going to be great—and that’s what being a spacefaring civilization is all about.”

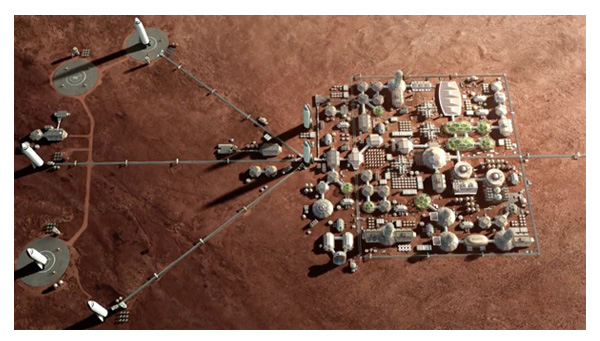

Musk’s Mars vision—let’s not call it a plan—has his company, SpaceX, running two cargo missions to Mars by 2022 that would place infrastructure, including for refuelling, to support future missions. It includes a crewed mission by 2024, followed by an awe-inspiring “base build-up.”

Musk acknowledges that, “when you seriously consider . . . a base on Mars,” you need “thousands of ships and tens of thousands of refilling operations,” demanding “hundreds of launches a day.”

Musk has been around long enough now to have a track record of over-promising and under-delivering. I cannot begin to take seriously his timeline for a first crewed mission to Mars.

Jeff Bezos is another billionaire, with much deeper pockets than Musk, developing space dreams through his company Blue Origin, on which he’s reputed to be spending a billion dollars a year, funded by selling his Amazon stock.

He discussed his vision, going to space to benefit Earth, in a 50-minute presentation on 9 May 2019.

His rationale for space is civilizational dynamism: a choice between stasis and rationing in an Earth-bound civilization, or one of dynamism and growth through moving out into space. To do this, he says, space travel needs to get a lot cheaper. He sees two gateways to progress: a radical reduction in launch costs through reusable launch vehicles; and the use of in-space resources—specifically, water from the Moon. Bezos says that, “our job, in this generation, is to build the infrastructure—to provide the low-cost access to space.”

Unlike Trump and Musk, Bezos doesn’t see Mars as a goal:

One thing that I find very unmotivating is the kind of Plan B argument: when Earth gets destroyed, you want to be somewhere else. That doesn’t work for me. We have sent robotic probes now to every place in the solar system, and this is the best one. It’s not close. My friends who want to move to Mars, I say, do me a favor and go live on the top of Mount Everest for a year first, and see if you like it, because it’s a garden paradise compared to Mars.

Instead, Bezos thinks the future of humans in space lies in giant space stations called O’Neill colonies, named after the American physicist Gerard O’Neill, who proposed they be built from materials sourced from the Moon, and from other asteroids. That they have to be built is hardly a downside—there is no natural environment in space in which humans could live outside of constructed infrastructures, not on the Moon, not on Mars, nor anywhere else, other than Earth. Bezos quotes Isaac Azimov’s remark that the common assumption that a space-based future will be planetary amounts to “planet chauvinism.” O’Neill colonies, Bezos says, can be close to Earth, making them easier to get to.

To get a sense of perspective on the issue of planetary distances, consider the sculpture conceived by artist Christopher Lansell, and designed, made and installed by Cameron Robbins, that is a one-to-one-billion scale model of the solar system on the foreshore of Port Philip Bay in Melbourne, Australia, The Solar System Trail.

To get a sense of perspective on the issue of planetary distances, consider the sculpture conceived by artist Christopher Lansell, and designed, made and installed by Cameron Robbins, that is a one-to-one-billion scale model of the solar system on the foreshore of Port Philip Bay in Melbourne, Australia, The Solar System Trail.

One metre in the scale-model sculpture is equivalent to one million kilometres in the actual solar system. The Earth is a chickpea-sized stainless steel ball, which sits on a plinth. The Moon is on the same plinth, 38 centimetres (15 inches) away. Mars, on the other hand, is 77 metres (253 feet) away. The outer planets stretch for miles along the foreshore.

The furthest any humans have been from Earth is 400,000 kilometres (250,000 miles), a record set when the crippled Apollo 13 swung around the far side of the moon in April 1970. That’s only 40 centimetres (16 inches) on the Melbourne solar system model. Yet these Apollo missions are epic voyages compared to other crewed space missions—the International Space Station is 408 kilometres from Earth, which would be less than half a millimetre (or about a sixty-fourth of an inch) on the model.

Mission duration is another lens through which to view the distance issue. The Apollo 11 mission that landed Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on the moon lasted 195 hours and some minutes—about eight-and-a-quarter days.

According to the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center website, the ideal line-up for a launch to Mars would get you to the planet in roughly nine months. But,

just like you have to wait for Earth and Mars to be in the proper position before you head to Mars, you also have to make sure that they are in the proper position before you head home. That means you will have to spend 3-4 months at Mars before you can begin your return trip. All in all, your trip to Mars would take about 21 months: 9 months to get there, 3 months there, and 9 months to get back. With our current rocket technology, there is no way around this.

Twenty-one months—about 630 days or more—some 75 times longer than the Apollo 11 mission.

So Bezos rejects Mars as too inhospitable and too far away. He is right.

Following the O’Neill script, Bezos announced in April that “it’s time to go back to the Moon, this time to stay,” and that Blue Origin intends to have its Blue Moon lunar lander take humans to the Moon by 2024. But his Moon mission is only “a necessary first step” to the O’Neill colonies.

Bezos transcends with colossal scale the claustrophobic confines of our images of space station interiors. His O’Neill colonies are huge rotating cylinders, housing a million people, with breathtaking scenery and their own weather patterns. Some, he says, could even be “national parks.” In place of the deadly reality of space, Bezos throws up a hospitable artificiality, with imagery that recalls the 19th century landscapes of the Hudson River School painters of the American sublime.

For a reality-check comparison, the largest habitable space environment built so far is the International Space Station, estimated to have cost $150 billion. It has the habitable space of a large house, with sleeping quarters for six, two bathrooms, a gym and a 360-degree view bay window. NASA and its international partners assembled its main modules over a decade, which involved 42 flights, 37 of them on the Space Shuttle.

Bezos wants to expand human civilization into the solar system at least in part to preserve our unique blue planet, which, he says, “will be zoned residential and light industry. We’ll have universities here and so on, but we won’t do heavy industry here. Why would we? This is the gem of the solar system. Why would we do heavy industry here? It’s nonsense.”

Yet there is a paradox. Bezos projects a residential, knowledge work, and light industry vision for our Earth, even while he also projects a sublime vision onto his space-based O’Neill colonies as beautiful places where people will want to go. Where will the heavy industry actually be? Perhaps on the Moon, or perhaps there will be special purpose O’Neill colonies devoted to heavy industries, like steel and chemicals, which he is yet to render into the narrative and the graphics he uses to advertise his vision. Norilsk, an industrial city of 175,000 in Siberia, dominated by mining and metal industries, built by Soviet gulag prisoners to exploit the region’s resources, might be an example of the kind of dedicated heavy-industry colony Bezos’s vision presumes, but hides from view.

In Bezos’s heavy-industries-off-Earth vision, how would any of the products of these industries get to Earth? Consider steel, perhaps the archetypal heavy industry. Would billets of steel, by the millions of tonnes per year, enter through the Earth’s atmosphere, to land—where, and how—on Earth? They’d still need to be made into girders, cars, ships, machines, and a myriad of products here on Earth. Or does Bezos imagine cargoes of finished goods, like cars, parachuting from space to show rooms all over the world? Apart from the sheer implausibility of the entry and landing, that would mean space-based facilities for all the materials that go into cars—including glass, plastics, rubber, electrics and the rest.

Large parts of the chemicals industry are based on organic feedstocks, like oil, natural gas, and coal tar. Coal and oil are not present in space. Methane, the main constituent of natural gas, is abundant on the gas-giant planets of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, but it is inaccessible due to their extreme gravity or distance. There is methane on Saturn’s moon Titan, but it too is a very long way away. Mars has trace quantities unlikely to provide a viable feedstock. Almost all the methane on Earth is of biological origin—living organisms made it.

Before leaving Bezos and his cosmic vision, remember that the Moon is no pushover. Lunar dust is one aspect of operations on the Moon that is not well understood by the public. There is no atmosphere or running water on the Moon, so there is no erosion to smooth the surfaces of the fine particles created by asteroid impacts and lunar volcanic activity. Moon dust, known as regolith, is everywhere, is sharp-edged, and it sticks to everything. Once inside a spacecraft, in zero gravity it floats freely, getting into astronauts eyes and airways, and into spacecraft equipment. NASA reviewed in 2006 the Apollo experience with moon dust in preparation for future return-to-the-moon missions. Apollo 17 astronaut Gene Cernan’s description, quoted in the report, is worth reflecting on when considering the breezy visions for moon bases to provide materials for further space exploration:

Dust—I think probably the most aggravating, restricting facets of lunar surface explorations is the dust and its adherence to everything no matter what kind of material, whether it be skin, suit material, metal, no matter what it be and its restrictive friction-like action to everything it gets on.

The report concludes that, “for lunar exploration missions, perhaps its greatest challenge will be to learn to live with lunar dust.”

Beyond the utopian, science-fiction visions of billionaires, what about an actual plan. NASA is charged under Trump’s Directive to go to the Moon and to Mars. With its international space agency partners, NASA outlined a Global Exploration Roadmap in 2018.

Read more in New English Review:

• A Detransitioner’s Story

• Gratitude and Grumbling

• Are We Really in the Back Row?

Congress asked NASA to contract an independent evaluation, which was done by the Science and Technology Policy Institute (STPI) of the Institute for Defence Analyses.

The STPI report summarises NASA’s plans as follows:

Under current and notional NASA plans, the Gateway, a small human-tended station in orbit around the Moon, would be assembled in space between 2023 and 2026 for the purpose of providing a platform to study the lunar environment, gain deep space operational experience, and stage missions to the Moon and Mars. Human missions to the Gateway are to be launched using the Space Launch System and the Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle (Orion). While not explicitly noted in current NASA plans or budget requests, the next step for a human orbital mission to Mars would be the formulation, design, fabrication, assembly, integration, and testing of the Deep Space Transport (DST), a vehicle that will take a crew to Mars orbit. After several years of in-space testing, the DST will depart on a 1,100-day crewed mission to Mars orbit.

The report concludes that: “A Mars orbital mission could be carried out no earlier than the 2037 orbital window without accepting large technology development, schedule delay, cost overrun, and budget shortfall risks. Further budget shortfalls or delays in the construction or testing of the DST would likely require the mission to depart for Mars in 2039 at the earliest.” The report assesses total system costs from 2019 through to 2037 at $184 billion, in 2017 dollars. The human mission to Mars orbit is $83 billion of that total, with the balance covering lunar missions and other human spaceflight. And that doesn’t get boots on the ground on Mars—only an orbital mission.

This schedule rests on two critical assumptions. NASA must settle the Mars orbital mission design promptly, because it drives the development of the Deep Space Transport, and not spend too much budget on Gateway and lunar operations, which would throttle its ability to devote resources to the Mars objective.

Since the report came out, Vice-President Pence has accelerated the timing for the Moon mission to 2024. NASA has responded by cutting the Gateway to a “minimum configuration” in the first instance, getting “stronger commercial engagement sooner” and “focussed urgency and energy to accomplish 2024.”

The Mars Society, while welcoming the Pence statement, is critical of the Gateway concept, which it calls a “Tollbooth.” President of the Society, Robert Zubrin, argues for a “Moon Direct” approach—not via the Gateway.

Zubrin also argues for a Mars Direct approach to missions to that planet, rather than staging them from the Gateway.

With the changing destinations favoured for human space exploration, I have some sympathy for NASA’s Associate Administrator for Human Exploration and Operations, Bill Gerstenmaier, who defends Gateway as an “adaptable” platform.

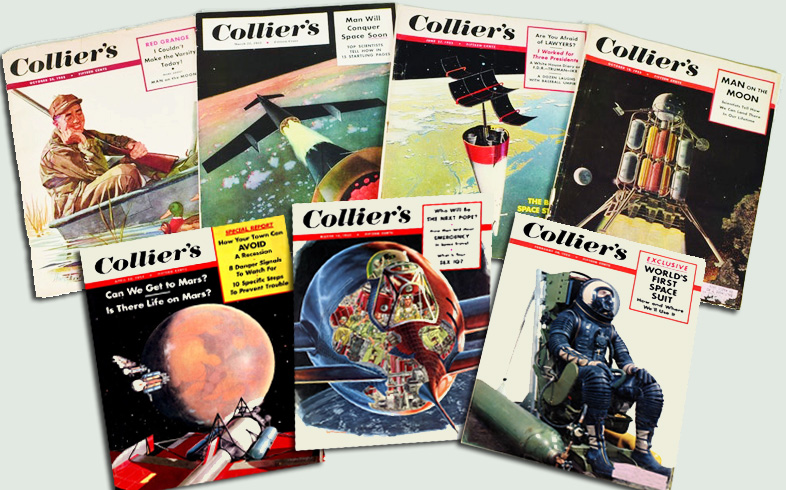

Wernher von Braun made the case for space to the American public in the early 1950s in a series of illustrated features in Collier’s called “Man Will Conquer Space Soon.”

It was also the basis for an animated Disney series, one episode of which was called “Mars and Beyond.”

This episode speculates about the existence of life on Mars and says that, on Mars, human “life could be almost normal, within pressurised houses, and pressurised cities.” As motivation, it says, “today, as we face the serious problems of overpopulation and depletion of natural resources, the possibility of Mars becoming a new frontier is of increasing importance in our plans for the future.”

Robotic missions have put paid to the speculations in the Disney animation about life on Mars. But the essence of heroic myth making, of mankind transcending the resource limits of the Earth and establishing a new frontier, remains virtually unchanged.

Robert Zubrin says in his new book, The Case for Space, that in the 50 years since Apollo, “our robotic planetary program has performed epic deeds of exploration, while our human spaceflight effort has stagnated.” He thinks we’re “poised for a breakout” driven by a new entrepreneurial spirit in the space industry, led by Bezos, Musk and others. This motivates him to outline his vision for what we might achieve in the next 50 years—that is, by 2069.

We will have fusion power and open-sea marine aquaculture and no longer be living in fear of climate change and resource exhaustion, or each other. We’ll be a cosmopolitan civilization, able to travel the globe freely through suborbital space in less than an hour, so that nearly everyone will have friends in nearly every land. We’ll have research laboratories, industries and hotels in orbit . . . There will be . . . cheap lifting of propellants to lunar orbit to support exploration missions to the outer solar system. We will have city states on Mars—vibrant optimistic centers of invention, sporting lively and novel cultures, with many casting off the chains of tradition to strike out on new paths to show the way to a better future.

The techno-jingoism of Musk, Bezos and Zubrin will animate the faithful of the space-enthusiast community. But, since the triumph of Apollo, it has failed to mobilise widespread public excitement. The International Space Station is moribund. Many young people are more interested in NASA for its climate work than its exploration agenda. The transcendent visions fall flat.

“Americans want rich guys like Elon Musk to pay for space travel—not taxpayers,” said the headline of a 2015 story in The Washington Post on American attitudes to space.

The survey on which the story was based found that, “less than half the public supports spending billions of dollars specifically to send astronauts back to the moon or to other planets.” Women are significantly less supportive of such spending than are men.

Jeff Foust, senior staff writer at Space News, tacitly acknowledged the softness of public support for space exploration when he concluded a review of a collection of von Braun’s speeches with the comment that, “A half-century after the dawn of the Space Age, anyone who wants to step into the shoes of von Braun will have to do a better job articulating why we should explore space if such programs are to have a stable, if not vibrant, long-term future.”

So, it’s time to consider program budgets. The STPI report on NASA’s plans for Mars looks at two budget scenarios: that NASA’s budget keeps pace with inflation; or that it grows faster, in line with US gross domestic product. It concludes NASA would have enough money for the human space flight programs including an orbital Mars mission over the 2019-2037 timeframe, but the higher budgets would allow a buffer to mitigate cost overruns or allow for additional missions.

Given past experience, can there be any doubt that cost overruns are virtually certain on a two-decade long complex human space program? This will drive proposals for additional funding, beyond inflation, in the face of serious pressures on budgets from other demands—renewing infrastructure, healthcare and aging, adapting to and mitigating climate change, tax and social security reform, and defence and national security in a world of increasing international strategic competition, to name just a few. The main alternative to additional funding for space exploration will be schedule delays. The other possibility is that Bezos’s and Musk’s development of reusable vehicles significantly reduces launch costs, though this remains to be demonstrated. We’ll also have to wait and see how this approach survives a fatal launch accident involving a used launch vehicle.

Space exploration has already found it hard to maintain a stable goal—is it the Moon, space stations, or Mars? Its rationale is tired and unconvincing to many. It is also incoherent—can the techno-utopians argue that robots and artificial intelligence will eclipse human work on Earth, while simultaneously arguing for the unique role of humans as essential to extremely dangerous and dull work in space?

With cost overruns and schedule delays virtually certain, and stable goals and budgets only an even-money bet, the timeframes for a crewed orbital mission to Mars will surely extend beyond 2040.

Wernher von Braun, in his 1954 article for Collier’s co-authored with Cornelius Ryan, asked whether man would ever go to Mars. He answered, “I’m sure he will—but it will be a century or more before he is ready.”

On current plans, von Braun’s century or more from 1954 is not likely to underestimate the timeframe—we won’t get to Mars, boots on the ground, before 2054. But will the transcendent vision for human space exploration sustain sufficient interest and funding for another generation against the demands of other priorities? The question is rhetorical, because the reality is we’ve already moved on. We will not go to Mars.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

__________________________________

Adam Selene has a PhD in Systems Engineering.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast