Welcoming the Apocalypse

by Matthew Wardour (November 2019)

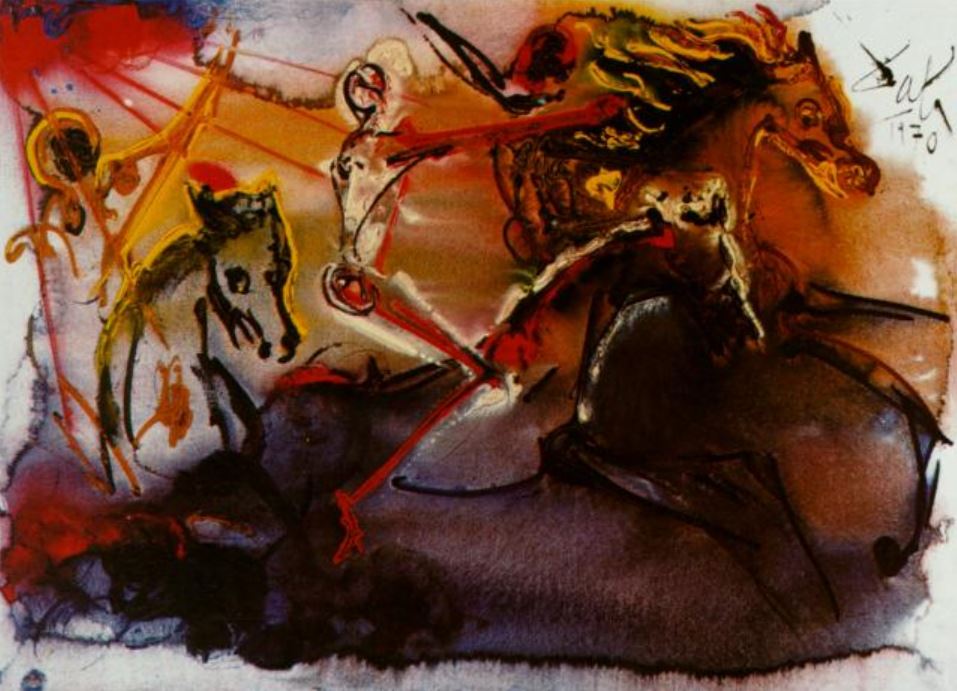

The Horseman of the Apocalypse, Salvador Dali, 1970

In John Wyndham’s apocalyptic novel The Day of the Triffids, mass blindness, ostensibly caused by a meteor shower, brings about the instantaneous collapse of society. As a result, carnivorous plants called triffids begin to make prey of humans. In the book’s opening chapters, Bill Masen wakes up in a hospital, his eyes bandaged and therefore unharmed by the meteor shower, to discover that chaos reigns and society is no more. One of the first things he feels is liberated:

. . . what had seemed at times a rather empty existence turned out now to be lucky. My mother and father were dead, my one attempt to marry had miscarried some years before, and there was no particular person dependent on me. And, curiously, what I found that I did feel—with a consciousness that it was against what I ought to be feeling—was release . . .

All the old problems, the stale ones, both personal and general, had been solved by one mighty slash. Heaven alone knew what might arise—and it looked as though there would be plenty of them—but they would be new. I was emerging as my own master, and no longer a cog. It might well be a world full of horrors and dangers that I should have to face, but I could take my own steps to deal with it—would no longer be shoved hither and thither by forces and interests that I neither understood nor cared about.

Bill Masen is uncannily like many people today. Someone who is neither responsible nor dependent upon anyone in particular, be it family or community. Someone who feels himself as an unimportant and inconsequential “cog.” He is thrilled at the thought of becoming “my own master,” made possible by the collapse of society.

Read more in New English Review:

• Traversing the Landscape of Gender Politics, Pt.1

• Dirty Politics of Climate Change

• There’s Magic in the Air

Indeed, barbarism can be much more appealing than civilisation. In order to maintain itself, civilisation requires institutions—moral, social and physical—that are often, as their critics rightly point out, oppressive and restrictive. But order and peace rely on these restrictions, and it is within these boundaries that people can truly possess liberty. Many have entirely forgotten, like Bill Masen, why such structures exist. They are only able to see the faults of institutions, and they rejoice when institutions are reformed or even abolished. For them, much that is important about these institutions is arbitrary or wicked. The monarchy is a peculiar anachronism, or at worst a tyranny. Laws against drug use are useless and “discriminatory.” Voting restrictions on the young and prisoners are merely exercises of power by an elite that wishes to preserve itself. Christian morality is a superstitious vestige from an unenlightened time. Marriage is (or was) merely a way to maintain the patriarchy.

Modern Britain prides itself on having liberated its people from many such institutions and beliefs. However, the newfound freedoms, often presented as “human rights,” are not the ones that most matter. In an ordered society one can maximise freedom of speech, but freedom of “expression,” or of self-abuse and gratification (which is usually a more accurate description), has to be limited. In the barbaric society, it is the other way around. Thought, in such societies, has an insignificant place, and so therefore does art and culture. But mores and morals are looser; there is more that a man can get away with, less that is fixed in his beliefs.

I fear this is the direction of most Western countries today. Freedom of conscience has less appeal to people than freedom of expression, and so if someone’s beliefs conflict with someone else’s freedom of expression, it is freedom of belief that is suppressed. This is why we as a society increasingly treat religion as merely a system of practices, not beliefs. Modern British society’s ready endorsement of Islam, for example, is contradicted by its abhorrence of many mainstream Muslim beliefs. Expression and identity are more important than speech and thought.

The danger of this attitude should be obvious to everyone, yet clearly it is not. We are, as a recent survey from the Policy Institute at King’s College London shows, becoming much more tolerant of drug use, abortion, scientific experimentation on embryos, homosexuality, divorce, sex and violence on television, even soccer hooliganism. This revolutionary change is almost never reported with any kind of concern; on the contrary, it is usually celebrated. We live in a society of rampant and unpoliced drug use, where antisocial hooliganesque behaviour is a fact of daily life, where 200,000 unborn babies are killed each year (and a majority of the public, moreover, apparently supports experimenting on them), where families are broken apart, where most of the media, entertainment industry and the general public enthusiastically affirm all these things and increasingly condemns those who do not. Are we, like Bill Mason, welcoming the apocalypse?

The triffids were plants which people grew in their garden, which society thought they could tame in spite of the obvious and fatal dangers, and which industries thought they could profit on because a great deal of oil could be extracted from them. In other words, society let it happen. Our society will go the same way. We have already planted the seeds of our destruction in our gardens.

There are no strong institutions left to assist us. It would be hard for anyone in modern Britain to be optimistic about the role of our dying churches, our militarised yet ineffective police, our unloved law and traditions, our art and literature. And the political system is increasingly at the mercy of the demos, who generally prefer radicalism of one kind or another to the imperfection of tradition and moderation. Conservative-minded voters, in their panic and anger, tend to elect vulgar caricatures of patriotism—men who, to quote Samuel Johnson, “have the external appearance of a patriot, [though] without the constituent qualities; as false coins have often lustre, though they want weight.”

I often feel like I am living in the alternative Britain of that astonishing yet forgotten final series of Nigel Kneale’s Quatermass—at least in its early stages. In Kneale’s imagined near-future, police no longer patrol urban areas; they have no authority and have been replaced by “pay cops.” Before, “you could walk in the open and not be afraid.” No longer. Sciences and arts are seen as threats to the young whose only impulse is to destroy; they have given up not merely on society but on the planet. Television has degenerated into sex and violence and various stupid programmes with onomatopoeic names; the few serious programmes that are broadcast are hardly watched. A fortunate minority can live separately from it all, but most have to endure the wretchedness of this urban collapse.

Read more in New English Review:

• Welcoming the Apocalypse

• Rouhani, Erdogan, and Putin: Masters of Geopolitics

• Past and Future Gulags, Pt 2

Future generations, for whom our technological civilisation will be but a point in history, will wonder, resentfully, why we had so much and yet did so little with it. The answer may be that we simply have too much, and in the same way that a man with too much on his plate can no longer stomach his life, our civilisation is overburdened and will therefore collapse. We have more debt than we can sustain, more people than we can support, far more goods than we can and should consume, and most of all, far more desires than can ever be satisfied, yet desires we are told we have a moral and psychological obligation to satisfy.

“You know,” says Josella in The Day of the Triffids, “the shocking thing about it is to realise how easily we have lost a world that seemed so safe and certain.”

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

__________________________________

Matthew Wardour is an English musician and occasional writer. He blogs on culture, politics and other things which catch his fancy at smelfungus.blogspot.com

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast