When Nobody’s Home

By Anthony Alicata (September 2018)

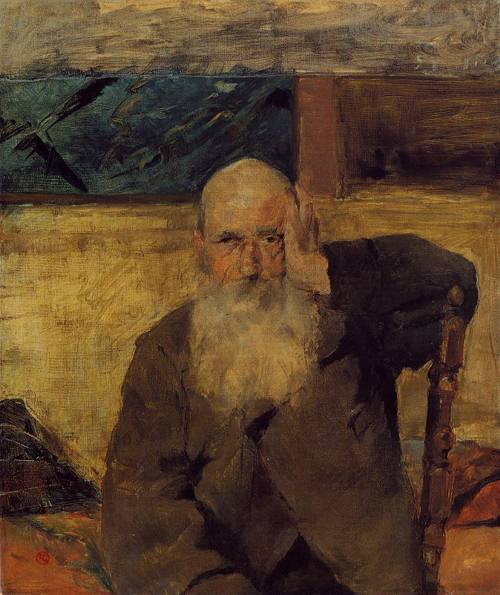

Old Man at Celeyran, Henri Toulouse Lautrec, 1882

The nursing home—compromise between life and death. A place to be when you’re too old for heaven and too young for hell.

It’s the purgatory they take you to when you make the fatal mistake of falling down when nobody else is home.

“That’s it folks. We can’t leave him alone—he fell down!”

Maybe that’s why old people are so slow and careful. They know what we’ll do to them if they fall. Maybe they pretend to be old. Maybe they can run and jump—but they know if we catch them falling we won’t find it cute anymore. We won’t ask them to get up again and come to daddy—we’ll tell them to lie down and not to move.

It was a cold night, but the air was still. We pulled my father’s middle-class, three-year-old Buick up to a curb a block from the nursing home—directly across from a cemetery. How convenient.

It was incongruous that there were no parking spaces on a block consisting of a cemetery and a nursing home.

Certainly, nobody rises from those cold patches of ground to drive off for a spin. The dutiful monthly visits of guilt-ridden sons and daughters to obsolete parents couldn’t account for the absence of open parking spots.

We approach what looks like a cottage. Quaint wood frame windows, a little Norman Rockwell porch. For a second I forgot we’re entering a home for sick, old, useless people. But when the nurse opens the door, and you are struck with that unmistakable “Institution” aroma— your doubts subside, and stop.

I used to hear of his large, powerful hands. How he had fought the Turks, and worked the pushcart.

He sat in a corner—very small, very thin. The large hands were obvious, hanging ominously from a mismatched body. No signs of the Great Warrior, no signs of the man who ruled his family with an iron fist.

The room was misleading at first, like the porch. It was bright and full of “house-like” fixtures. But, closer inspection brought hospital beds, walkers, turquoise water pitchers, and cafeteria trays into focus.

When you’re old and dying does the color of the wallpaper matter?

As I came closer to him I noticed his eyes. They were wide open, almost excessively so. Why are old people’s eyes always so wide, so alive, so sparkling?

This man’s eyes are so penetrating. Maybe everything else is so still that there’s just nothing to distract me from them.

Do those eyes hold a secret that I can learn if I look hard enough?

I smile and kiss him.

He seems to know who I am. My father makes endless small talk with him.

My grandfather’s speech is slow and slurred, but I could see him ready for the task. He sits quite straight, and fixes me with his eyes, takes an invisible breath and churns out his message.

Certain subjects, or words, or impulses impossible for me to detect make him start to cry.

As soon as I had walked in I knew that he’d wanted to cry, desperate wailing tears.

He stops himself. With great effort he tightens his lips, his eyes glaze over, his chest heaves, but he won’t cry. And my father helps him—he changes the subject. My father always changes the subject.

It’s time for their supper and a nurse brings in a tray . . . a hot dog, soup, and coffee.

I watch my grandfather eat. When he finishes his meal, we talk some more.

My father glances at his watch. He wants to leave. It is time to go. We must go. Leaving. No human action is more devastating than the act of leaving. It doesn’t matter who or what you’re leaving . . . somebody gets hurt.

I realized that what my father was leaving was his future.

Then a terrible thing happened. As we were about to leave, my grandfather introduced me to someone as his daughter’s son, Peter. All this time he didn’t know who I was. I was there with my father, his son, and he didn’t know who I was.

It was an honest mistake. The old man hadn’t seen me for a long time, and my cousin Peter is a big 21-year-old with a beard just like mine.

But, then, I made a mistake. I corrected him.

When my father and I reached the porch, my father turned to me and said, “It’s things like this that should make us live every day to the fullest.” “Yeah, dad. But nobody ever does, do they?”

But nobody ever does that, do they? We all fall down alone, when no one else is at home.

This true story originally appeared in the Boston Globe Sunday magazine “New England” in 1977. Published with the author’s permission.

______________________________

Anthony Alicata is a retired professional actor and director.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast