Cancel Culture for Communists

by Theodore Dalrymple

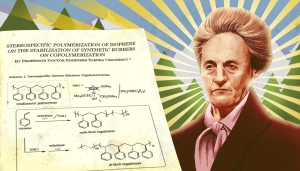

I happened to be in Romania three months before the downfall of Ceaușescu and his wife. I was surprised to find, among all the shortages, a plentiful supply of a book titled Stereospecific Polymerization of Isoprene. It was evidently a best-seller in the Romania of the time, or at any rate a much-displayed item in the shop windows when little else was displayed. Was it that the Romanians, despite having to line up for hours even for a few mouldy potatoes, were fanatical amateurs of organic chemistry (polymers of isoprene occur in rubber)?

The name of the supposed author of the book provided a clue to the curious omnipresence of so obscure a title: none other than Elena Ceaușescu, D.Sc. Of course, everyone knew that she hadn’t written it and that she had never been the chemist that she claimed to be. But they had to pretend not to know it. Officially, Elena Ceaușescu was a world-renowned researcher in chemistry, though apparently in real life she could not recognise the chemical formula for sulphuric acid, having once been only an unskilled assistant in a chemistry lab. The book, published in several languages, is now something of a collector’s item.

Thirty years after her death (in essence, her murder) there are calls in Romania for the authorship of “her” book to be annulled, for the scientific papers of which she was allegedly the first author to be retracted, for her doctorate to be abrogated, and for the foreign honours she received, especially from scientific institutions, to be withdrawn.

Nobody now will be found who would claim that she was, in fact, a chemist of repute, that she earned her doctorate (by law in Romania at the time, doctorates had to be defended in public, but she defended hers in camera), that she ever wrote a book, that she was the first author of anything except her own downfall, or that she deserved to be honoured by universities and scientific societies.

Nor is it very likely that annulation, retraction, and withdrawal will make much practical difference to the world. Although everyone knows that she was not the author of “her” scientific papers, no one has suggested that the work described in them was bogus, forged, or falsified: simply that it was done by people other than she. Moreover, science moves on: except for a very few papers of enormous historical scientific importance, no one would read papers of organic chemistry published forty or fifty years ago. The book is a collector’s item precisely because everyone knows it to be falsely attributed to the Lady Macbeth of Romania. As to the foreign honours conferred upon her, their removal would make no tangible difference to anyone’s life.

But man, being blessed with consciousness, is a creature that disputes and even fights over symbols. That is why argument over the removal of public statues is so bitter, especially in the face of intractable social realities that are so humiliatingly difficult to change. (I do not recall anyone ever having defended statues on purely aesthetic grounds, namely that they are attractive to look at and, given our own age’s incompetence in the matter of public statuary, suffering as we do from a total inability to replace them with anything of equal aesthetic value, they are best left alone.)

If honours can be withdrawn once it becomes politically expedient to do so, then not only are no honours permanent, but honours themselves become a permanent field for political dispute.

Public statues of figures who were important in the past often become in time purely ornamental, the pedestal for pigeons, for few remember precisely who they were or what they did, though this is obviously a matter of degree. At one end of the spectrum is a memorialised person whom not one in a thousand passers-by could name or for whom he could supply any biographical detail whatever; at the other end of the spectrum, most people could name and provide some biographical information about the memorialised person, for example Lenin. Where such a person is well-known, it is natural that the question of what he was well-known for becomes important. We would not take down a statue of Shakespeare because he conceived a child out of wedlock or left his wife only his second-best bed.

The Hungarians dealt very well with the matter. Statues of the hated (and in all conscience hateful) Lenin were everywhere before the liberation of the country from communism. Most of them were mass-produced and could hardly be called works of art, though they were the works of human labour. The best of them, or examples of the most characteristic, were preserved and placed in a park of such statuary in Budapest. This, it seems to me, was a perfect solution to the problem. It served as a reminder of a terrible past, it demonstrated that that terrible past was also preposterous, providing a warning to the future. But it preserved the products of human labour, some of which entailed skill.

As to books published under totalitarian regimes—the Complete Works of some monster or other (in various editions as required by changes in official doctrine): what should be done with them, considering that they were published in huge editions that no one really wanted? I remember visiting a prison in ex-Soviet Georgia after it became independent of the Soviet Union. The prisoners had at last found a use for the complete works of Lenin that they found in the prison library. They used the pages as lavatory paper, for none other being available, and the complete works consisted fortunately of many thousands of pages. Nevertheless, one would not want all copies of the complete works to disappear from the face of the earth forever, for not only are they of enormous historical significance but we do not want to totally eradicate any trace of our past, whatever it may be, and however lacking in relevance to our current concerns.

Coming now to Elena Ceaușescu and her legacy, I find myself without a clear doctrine. On the one hand, her name attaching to books and papers does disservice to and disrespects their real authors, some of them still alive; on the other hand, what more is to be done once the names of their real authors are published, especially as everyone already knows that Elena Ceaușescu was a chemist the way Sylvester Stallone is a heavyweight boxing champion of the world?

There is something to be said for and against the withdrawal of the honours she received (for example, from the British Royal Institute of Chemistry): she clearly didn’t deserve them but they were awarded as a matter of historical fact. If honours can be withdrawn once it becomes politically expedient to do so, then not only are no honours permanent, but honours themselves become a permanent field for political dispute, since no one apart from saints has no blemish on his record to be discovered by the assiduous termites of research.

On the whole, I think I would prefer the maintenance of the honours Elena Ceaușescu received to the re-writing of history, as a warning to the distributors of honours to be more careful in their selection of recipients (the Royal Society turned her down for its Fellowship). But having been in Romania just before her and her husband’s downfall, I can well understand the urge to deface her memory.

First published in Law and Liberty.