Chicago’s Mayor Celebrates Kwanzaa, While City Suffers Violence

The mayor of Chicago, Lori Lightfoot, wished the inhabitants of her city a happy Kwanzaa, the wholly invented African-American festival, which is about as African as Senator Warren’s descent is Amerindian. Ms Lightfoot made reference in her wishes to the seven guiding principles of Kwanzaa while her city was suffering yet more violence, and which, if applied, would allegedly lead to a better world, even a better Chicago.

The names of the festival and its seven associated principles are Swahili words, Swahili being the beautiful language of much of East Africa and the lingua franca of extensive parts of Central Africa.

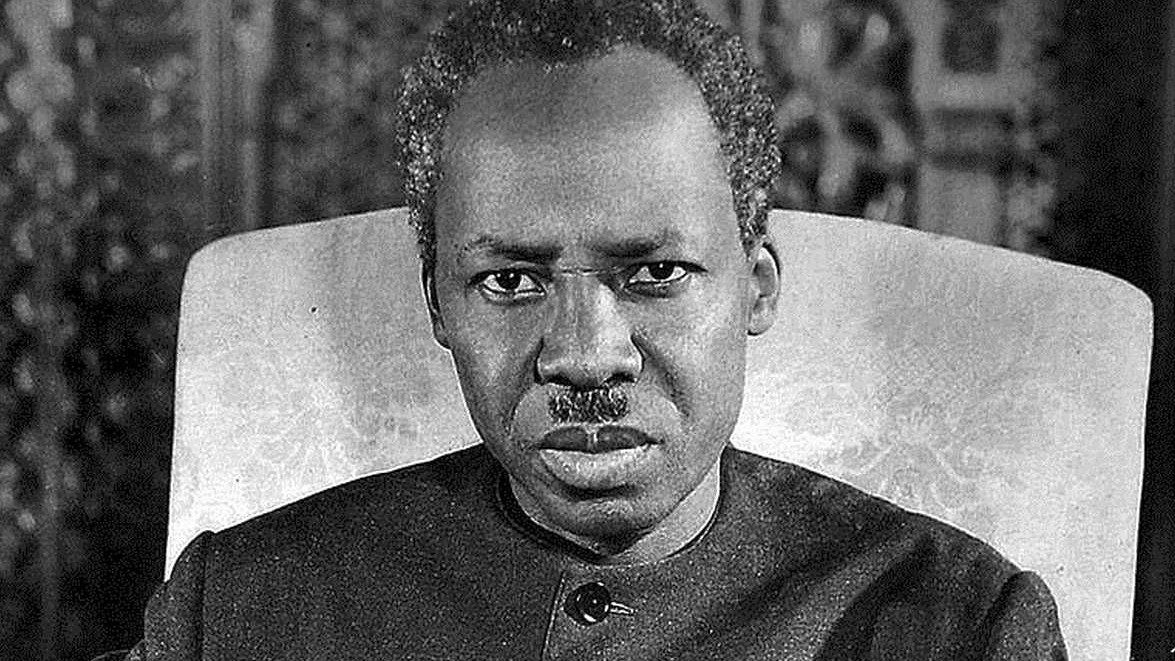

The seven principles of Kwanzaa owe much to the ideology of Julius Nyerere, the man who was President of Tanzania for a quarter of a century after independence from Britain, who was for long the darling of the European left and who reduced his country to an incredible state of beggary such that, although 90 per cent of the population worked on the land, it could not feed itself without foreign aid—more foreign aid than was received by any other country in Africa. I lived there for three years and then left to cross Africa from Zanzibar to Timbuktu by public transport.

To be fair (which I do not always find it easy to be), Nyerere was not the worst of the first generation of African dictators. Although he was ruthless in suppressing opposition and introduced an oppressive and economically disastrous totalitarian system, he was not a tribalist (which would have been impossible in any case because there were no would-be dominant tribes in his country), and he did not indulge in any of the more bizarre and terrible activities of Africa dictators such as Idi Amin, Sekou Touré, or Jean-Bédel Bokassa.

He learnt his socialism of the Fabian variety at Edinburgh University and then (according to Oscar Kambona, his exiled former associate and foreign minister, who fell out with him over the imposition of a one-party state with which he strongly disagreed) became Maoist on an official visit to China, where he was welcomed by vast dragooned crowds chanting his praise. This turned his head.

At any rate, he began to herd the peasantry of Tanzania into collective villages, known as “ujamaa” (brotherhood) villages. The results were catastrophic: not only was about 70 per cent of the population moved by various degrees of force and coercion from where it was living, but agricultural production began its long decline.

Practically all commercial farming, the country’s only source of foreign currency to pay for imports, was abandoned, and famine was averted only by foreign aid, principally from Scandinavian countries which subsequently recognised that they had, in effect, subsidized a great crime.

In ujamaa villages, Nyerere instigated the ten-cell system. Every tenth household had a party member (the party of the Revolution) whose permission was needed for any small privilege to be wrested from the authorities, and who in effect acted as a government spy.

Needless to say, this resulted in a swamp of corruption and blackmail, such that, in a country never far from hunger, party members could be recognised by their girth. The whole system was prevented from being horrific only by incompetence and the generally delightful and pacific nature of the Tanzanian population.

Ujamaa is one of the principles lauded by Mayor Lightfoot. It is a moot question whether, it would be worse before doing so if she knew what ujamaa meant in reality than if she didn’t.

Another of the principles of Kwanzaa is “uhuru,” or freedom. Freedom in Tanzania had little recognizable meaning. Only governmental incapacity or incompetence, and a certain laudable lack of ruthlessness by comparison with other dictatorships, prevented freedom from being extinguished altogether.

It was certainly not from any official attachment to it that there were worse places in this respect than Tanzania. Nevertheless, Nyerere held thousands of people without trial for political reasons.

“Umoja,” unity, is a third of the Kwanzaa principles that the Mayor lauded as a peculiarly African virtue. Let me here recall a few things about my journey across Africa, during which I saw the continent from the bottom up.

In Rwanda, every person was a member of the sole political party from birth; a few years later there was to be a genocide in which about 800,000 people were slaughtered by, among others, their neighbors.

Naturally, some people blame the colonial legacy for this, even though the country had been independent for a third of a century; moreover, you can lead a man to a machete without making him use it to commit genocide.

South of Rwanda, and in many respects a mirror-image of that country, was Burundi where, in 1972, every Hutu with a secondary education or above was massacred, between 100 and 200 thousand of them.

In Equatorial Guinea, the first president, democratically elected, had caused a third of the population either to be killed or to flee into exile. And thirty years later, much of my journey would have been too dangerous to make because of civil wars.

The war in the eastern Congo is estimated to have caused 3 million deaths; north-eastern Nigeria has been made impassable by Boko Haram (since succeeded by the Islamic Insurgency in West Africa), the Islamist terrorist movement, though at the time I had no inkling of the future. Mali has likewise become impassable because of such factional fighting. So much for umoja.

I draw attention to all this not because I think Africa is worse than anywhere else. Similar things, alas, could be recounted about most regions of the earth. I wish merely to point out the fatuity of the seven principles of Kwanzaa, which are supposedly characteristic of something called African culture.

But even to use the term African culture is indicative of a complete absence of real interest in Africa. Africans of East and West Africa are no more alike than are, say, Albanians and Swedes, indeed West Africans are not all alike in culture or philosophy of life.

The mayor’s use of Kwanzaa and its supposed seven principles deriving from African culture is purely demagogic, a tool of political entrepreneurism and rent-seeking, while ignoring problems such as drive-by shootings that are her responsibility to solve.