Craig Considine’s Sappy Syncretism

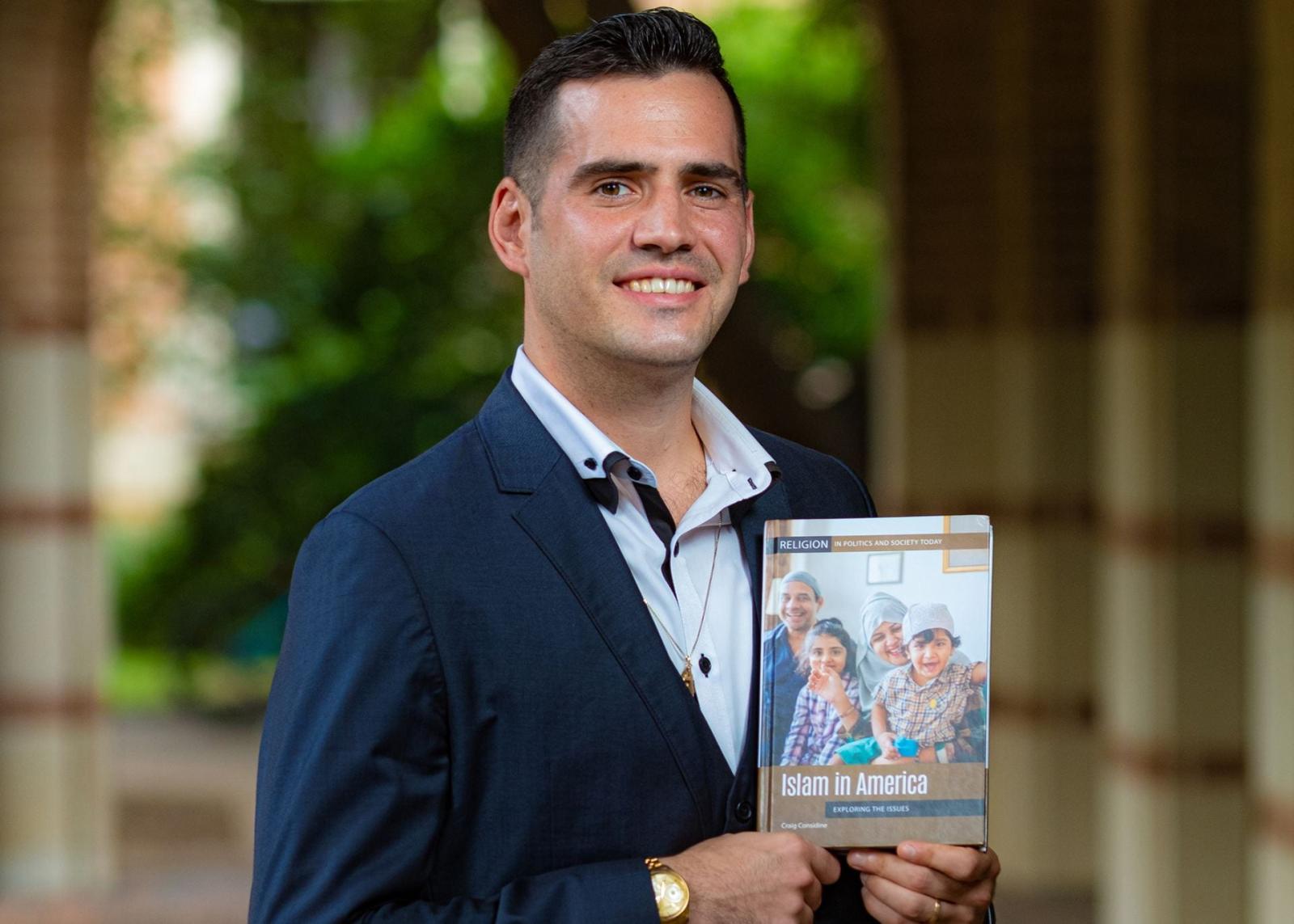

The November 11 American Muslim Institution (AMI) webinar “The History & Future of Muslim—Christian Relations” revealed yet again the emptiness of what often passes as Christian-Muslim dialogue. Rice University sociology lecturer Craig Considine and Cato Institute fellow Mustafa Akyol presented distorted pictures of both Christianity and Islam in their quest to downplay glaring differences between the world’s two largest religious bodies.

As moderator, AMI Executive Director Shahid Rahman opened the event by stressing the importance of a “good relationship” between Christians and Muslims, the world’s two largest religious communities, as “critical for global peace.” However, the only “tensions” between these faiths he mentioned were the long-ago Crusades, along with President George W. Bush’s one-time malapropic reference to them, and not Islamic jihad, to which the Crusades were a defensive reaction.

Rahman paired faulty history with dubious theology. “While theological differences definitely arise with respect to the entity that is Jesus, his role in both faiths are oversized and necessary,” he stated. Christian scholars, however, have noted for centuries how the messianic God-man Jesus of the New Testament diminishes to a prophet pointing towards Islam’s final prophet Muhammad in the Quran.

Questions of Jesus’ nature would be fundamental for any “practicing Roman Catholic,” as Rahman introduced Considine, yet this debunked Islam apologist displayed his usual superficiality. He noted that he “learned so much about Christianity through Mustafa’s book,” The Islamic Jesus: How the King of the Jews Became a Prophet of the Muslims (2017). This reading “really made me wonder when I was growing up in Boston going to Catholic school, why wasn’t I informed about the Nicene Creed, why wasn’t I informed about the Council of Nicaea?” he stated.

This is striking ignorance about the 325 A.D. Council of Nicaea in the Christianizing Roman empire and the Council’s namesake creed. Catholics and other Christians recite on most Sundays the Nicene Creed’s declaration of basic Christian doctrine. Any scholar of Christianity and Islam, much less an active Catholic like Considine, should have studied such a key matter in some depth.

Ever the syncretic fans of minimizing religious differences, Considine and Akyol emphasized the latter’s claim for a “Judeo-Christian-Islamic tradition.” “There is a Judeo-Christian tradition,” but “there is something missing there,” Akyol said; Considine responded, “you need a second hyphen there.” More serious Christian scholars have analyzed how such an “Abrahamic” faith trilogy overlooks profound theological divergences between Jews and Christians, whose scriptures Islam in turn appropriates for its theologically supremacist claims.

Considine displayed an even weaker grasp of history when discussing the Barbary Wars, in which the young American republic fought Muslim North African-based pirates during the nineteenth century’s first decades. He made the commonplace observation that America’s 1797 treaty with Tripoli declares that America is not a Christian nation in order to substantiate typical leftist claims about America’s supposed secularity. Yet American diplomats agreed to these terms as a way of signaling their Muslim counterparts that America was not a theocracy that would ever want to engage in a religious war.

Such messaging appeared vital given that the Barbary Wars were merely one episode in centuries of jihadist slave-raiding against European coastal towns and merchant ships like America’s sailing the Mediterranean. Beginning with the Islamic conquests of North Africa in the seventh century, such aggression had devastating effects upon European civilization. Nonetheless, Considine reduced the Barbary Wars to merely a brief post-1797 episode, as the “Barbary Wars happened shortly after that and the treaty kind of crumbles away.” “The top scholars say that religion did not spark that conflict; it was politics, it was people breaking treaties,” he added while discussing violence that everyone at the time viewed as religious in nature.

With Akyol’s approval, Considine reprised his canard that Muhammad’s interactions with the Najran community of Christians in seventh-century Arabia manifested interreligious tolerance. Considine also marveled that “incredible interfaith work has unfolded in Mosul, a city really ransacked by imperial powers and also by ISIS” (Islamic State in Iraq and Syria), as if America had never helped to rebuild Iraq. There, Muslim collaboration in rebuilding Christian churches “is really quite reflective of some of the documented agreements he had with the Christians,” he said, invoking a number of historical forgeries.

Sticking with his theme, Considine stated that Muslims in Christian-majority nations endure indignities and dangers similar to those suffered by Christians in Muslim-majority countries, declaring “The hardest places in the world to be a Christian are arguably in Muslim-majority countries and then we could flip it with Muslims who have a difficult time in certain European countries.” This proved too much even for Akyol, who objected that the “places that are worst for Muslims are not Christian-majority countries,” which today are mostly liberal democracies with religious freedom. He pointed rather to countries like China or and Burma, where Muslims suffer genocide and ethnic cleansing.

In a forthcoming book, Akyol wants to “tell the story of Muslims and Jews . . . until the twentieth century mostly a bright story” of “mutual enrichment,” he said, echoing the myth that Jews found tolerance in Muslim societies. This “is much needed,” Considine agreed, apparently missing the contradictions born of his persistent condemnations of Israel as an imperialist, racist power. Concerning the Quran’s treatment of Jews, “if you read literally without any context, it doesn’t sound great, but it is not speaking about Jews for eternity,” he stated, ignoring that Islamic antisemitism has plagued Jews for centuries.

Considine conveniently overlooked such Jew-hatred in his praise of former Iranian president Muhammad Khatami’s 2007 Vatican visit while misidentifying the pope with whom he met as Francis. In fact, Benedict XVI received Khatami, whose successor, Hassan Rouhani, met with Francis in 2016. Considine uncritically celebrated Benedict’s call to Khatami for a “dialogue of civilizations,” even though Khatami represents Iran’s brutal theocracy.

Abetted by fellow apologists like Akyol, Considine’s flights of fantasy seem endless. More a popularizer of Islamist propaganda than scholar, he substitutes a saccharine multiculturalism for Islam’s long history of conflict with the West. Such “fantasy Islam” apologetics should have no place in academe.