For Israel, Uniqueness Must Always be Affirmed

by Louis René Beres

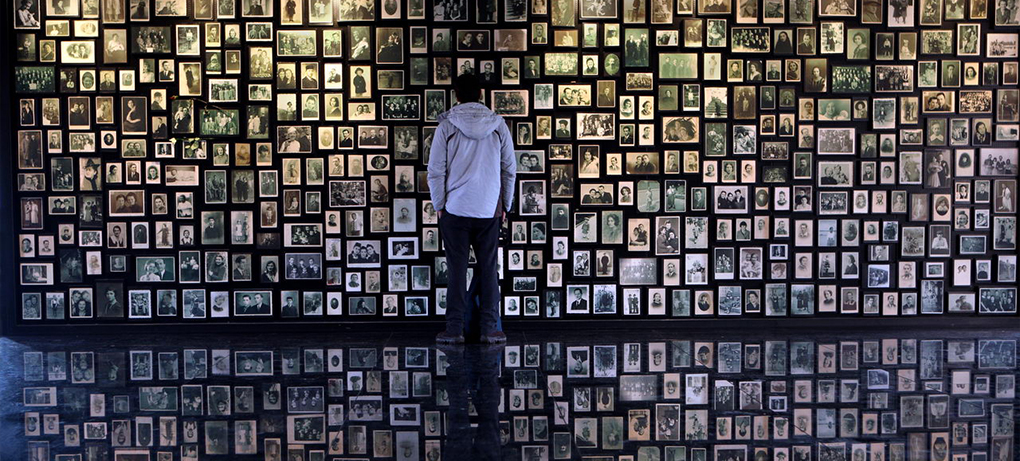

The Memorial Wall at Yad Vashem – the Wall of Holocaust and Heroism – has four separate sections, ranging (and rising) from the Shoah to Rebirth. Designed by Naftali Bezem, it directs us purposefully from an inferno, in which even the holy has been profaned, to the blessedly divine sanctuary of new and ever-growing Jewish generations. Still, however counterintuitive, these reborn generations, symbolized by the fearless countenance of a lion, must shed endless tears.

Why tears? It is because the Wall is most fundamentally about memory. Memory, it reveals so movingly, is indispensable to justice, and most particularly for Jews. Despite all of the lion’s greatness and strength, the Wall intones, even this king must never be allowed to forget. Never! Always, the Jew must weep knowingly for the past, but not gratuitously, not for sorrow’s sake. Instead, it is in order to be reminded of something far more rudimentary: the special and eternal Jewish responsibility to stand above the conspicuously larger human “herd,” always to do much more than just “fit in.”

Implicit, indelibly, in Bezem’s seemingly paradoxical imagery is the imprimatur of Jewish uniqueness. Without this acknowledged singularity, there can be no meaningful redemption, not for the Jews, and not for the wider world. In going up to The Land, Bezem’s “New Jew” resolutely affirms many things, but most particularly and emphatically that Israel will never permit itself to be regarded as merely one more codified set of geographic boundaries among the fractionated nations. It is an immutable affirmation.

There is more. To properly acknowledge the Jewish state’s uniqueness represents both an individual and a collective obligation.

The latter, moreover, is not possible without the former. Facing the world without a deeply felt sense of historical and prophetic difference, the Jewish state, always the individual Jew in macrocosm, can never muster the spiritual strength it will need merely to survive.

Even if endowed with a genuinely resilient national nuclear strategy, an “opaque” endowment that must seem both plausible and compelling, Israel must require this special sense. Absolutely.

On this pertinent sense, moreover, the prescient wisdom of Martin Buber can be instructive: “There is no re-establishing of Israel,” warned the twentieth-century Jewish philosopher, “there is no security for it save one: it must assume the burden of its uniqueness….”

Yet, today, Israel remains effectively beleaguered and cross-pressured by a markedly contrary ethos.

Indeed, for some time now, much of Israel has plainly wanted very much just to be like everyone else. Above all, it appears, this significant portion of the citizenry still wants to be left to “fit in” with the rest of world, that is, to be regarded as just another person, and not always as “The Jew.” Still, if Israel were ever collectively “successful” in this myopic ambition, the resultant triumph of uniformity, of manifestly shallow goals and materialized values, could substantially undermine Israel’s intrinsic worth, and, correspondingly, its physical security. It’s not that there is necessarily something wrong with Israel’s Jews wanting to be regarded as just another member group of the broader human species, but that there also exists an overriding, antecedent and arguably sacramental Jewish obligation to remember.

Israel, of course, faces many genuine security threats, some of them even potentially existential. Understandably, these palpable perils, primarily the very evident risks of unconventional terrorism and unconventional war, correctly preoccupy Israel’s political leaders and strategic military planners.

But there are also certain less obvious threats, hazards that, at least in some respects, are every bit as serious, and even more ominously, closely interrelated, or occasionally discernibly “synergistic.”

In these less tangible synergies, the expectedly injurious “whole” must, simply by definition, emerge as greater than the sum of its parts.

A discoverable national retreat from Israeli Jewish uniqueness is already long underway, and easily detectable. To an extent, at least, it remains animated by a more-or-less conscious imitation of popular culture in the United States. For too many Israelis, let us be candid, the altogether optimal Jewish state is one that most closely resembles New York or Los Angeles. Could this utterly demeaning hope conceivably be why Israel had ingathered the surviving Jewish remnant after the Shoa? Could such a wish ever be reconciled with the peremptory obligations of Jewish memory? To be sure, for many fragile countries on this imperiled planet cultural imitation is not even a realistic choice. For a variety of reasons, most having to do with unyielding economic and systemic constraints, these generally less fortunate states are effectively consigned to mimicry by assorted circumstances that lie far beyond their effective control. In regard to these all-too-many desperate countries there is little to reasonably comment upon, or to critique.

Israel, however, is another matter entirely.

Some years back, Shimon Peres, then accepting a stunningly post-Zionist discourse that would have been incomprehensible to earlier generations of Israelis (on January 14, 1999, Peres enthusiastically congratulated the PLO on its “long struggle for national liberation”), set the stage for subsequent national surrenders. Among the most preposterous and unforgivable of these sequential surrenders were predictably periodic terrorist releases, blatantly unreciprocated acts of Israeli “largesse” that, unsurprisingly, regularly set free the next cast of Islamist terrorist murderers.

There has been a convenient “counter-discourse.”

It’s always charming, of course, to be reminded that Israel is a genuine world leader in science, medicine and technology, but such authentically extraordinary achievements will ultimately matter very little if the Jewish state continues to see itself in the distorting mirror of other states’ mundane preferences and expectations. Ironically, it is precisely because Israel’s enemies have singled it out for an invented “uniqueness” that they still prepare single-mindedly for its annihilation. The obligatory reciprocal task, for Israel, is to recognize and denounce this concocted definition, a murderous enemy initiative that is, once again, genocidal in intent, and replace it with a genuinely meaningful definition of its own.

In this suitably alternative Israeli Jewish concept of uniqueness, the core message – one deeply rooted in millennia of Jewish history – must be an unambiguous determination to survive as a state, and, as corollary, to firmly resist any manipulative or disingenuous proposals for regional “peace.”

For Israel, whether a particular policy is named Oslo or Road Map or two-state solution should make no concrete difference.

The alleged promise of diplomatic peace with a plainly genocidal adversary – be it Fatah, Hamas, the Palestinian Authority, Islamic State or Iran – is inevitably a sordid and self-defiling offer. Of course, protracted war and terrorism can hardly seem a tolerable policy objective for Israel, but even such thoroughly difficult expectations remain better for Israel that starkly undiminished Palestinian/Iranian hopes for another Final Solution.

On a planet where evil too often remains banal, the primary origins of terrorism, war and genocide are not in individuals, but rather in whole societies that openly despise “the individual.” In such grievously corrosive societies, the mob is everything, and any desperate affirmations of human rights are routinely and systematically crushed.

Increasingly, surrounded by such mass societies, all of which seek to “fit in” themselves by keeping Israel “out,” Jerusalem may decide not to reject this terrible and terrifying mob. Sometimes, it may even be prepared to join it, and (however unwittingly) to honor it, by accepting various contrived resolutions, or by entering into assorted “authoritative” agreements.

In Naftali Bezem’s art, a ladder is the apt representation of aliya, of the Jew “going up” to The Land. It also arouses various creative associations with Jacob’s dream, and with certain Kabbalistic degrees of ascension.

By these visualized associations, the meaning of aliya is extended fittingly to illustrate Jewish fullness and perfection, conditions that must never be separated from an unhindered awareness of Jewish national uniqueness.

First published in The Jerusalem Post