How Multiculturalism Hijacked Feminism

by Phillis Chesler

In my college and graduate school days, we knew absolutely nothing about our feminist foremothers or about their campaigns for equality and freedom.

I did not know that women were oppressed and that feminists had battled for women’s rights for many centuries.

Earlier feminist writers (Mary Wollstonecraft, Sojourner Truth, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Charlotte Perkins Gilman) were unknown to most of my generation. We did not know how hard they had had to fight and how much they had disagreed with one another.

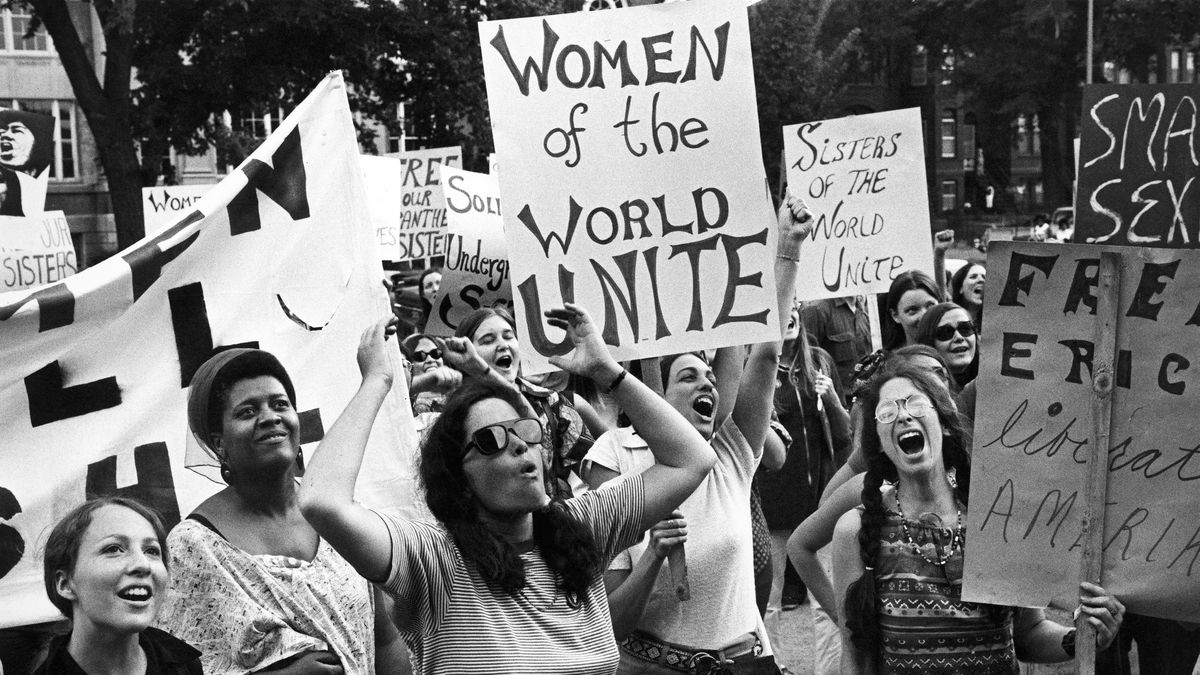

My generation (1963-1980) launched “speak-outs” on violence against women, established rape crisis hotlines and shelters for battered women, brought class-action lawsuits, implemented feminist ideas within our professions, and fought to pass an Equal Rights Amendment.

In 1975, Lin Farley coined the phrase “sexual harassment” and published a book about it in 1978; Catharine MacKinnon did so in 1979.

Perhaps if this history had continued to be taught, it might have armed the coming generations and served as a warning to predators.

What if students—the future American journalists, actors, and opinion makers—had been taught that they were part of an honorable historical struggle to expose and abolish sexual violence against women? Would presidents and media moguls have been allowed to sexually harass and assault so many women without being outed, shamed, and stopped long ago?

In 1982, in “Women of Ideas and What Men Have Done to Them,” Australian scholar Dale Spender documented how pioneering feminist work has always been systematically disappeared.

Guess what? By the mid-1980s, radical feminist works by the best minds of my generation were out of print and/or not being taught in college or graduate schools. By the late 1980s, professors and their students were largely unfamiliar with most of our work.

I am referring to: Louise Armstrong, Ti-Grace Atkinson, Kathy Barry, Mary Daly, Andrea Dworkin, Shulamith Firestone, Kate Millett, Janice Raymond, Diana Russell—and the incomparable writings of New York Radical Women and Cell 16, and their grassroots counterparts across the country.

All these radical thinkers happen to be Caucasian. I myself am not sure what to make of this other than that many of us were relatively privileged (in terms of race) and could therefore afford to focus on gender and not, simultaneously, on race and ethnicity.

Feminist women of color were definitely present but they were in the minority. Their lives forced them to wrestle with race as well as gender; the demand for loyalty to their race-based community also claimed their attention. White girls were always apologizing—and being castigated—for how few women of color joined us at marches and conferences, or who published pioneering work between 1963-1980.

In the 1970s, some African-American feminists published position papers (Combahee River Collective), essays and anthologies (Toni Cade Bambara, Frances Beale, Barbara Smith), poems (June Jordan, Pat Parker) and books (Audre Lorde, Dorothy Sterling, Alice Walker, Michelle Wallace). I cited them in my early work. While some names may have been forgotten, their primary insistence that race, ethnicity, geography, etc., are as important—perhaps more important—than gender has prevailed in the academy.

For example: Harvard’s 2018-2019 course offerings include: “’Ain’t I a Woman?’ Gender and Sexuality in the Caribbean and the African Americas”; and “Beyoncé Feminism, Rihanna Womanism: Popular Music and Black Feminist Theory.” Stanford offers: “Intersectionality and Social Movements: Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Collective Organizing.” Yale offers “Transnational Approaches to Gender and Sexuality.”

What ever happened to our focus on women?

We underestimated both the threat that we posed to the status quo and the determination of our opponents, both male and female. Had we prevailed, sexual violence might have decreased or been better prosecuted. Perhaps the battle for women’s reproductive rights might have been more successful.

Although women’s studies as a ghetto was absorbed by the academy, our woman-specific ideas never gained much institutional or ideological traction. Preoccupation with gender identity trumped gender. Women’s studies became “Gender and Sexuality Studies.” Race, class, and sexual preference trumped incest, rape, domestic violence, pornography, and sex slavery, despite the fact that women of all classes and races endure such assaults.

The academy prides itself on maintaining a global consciousness; however, an internet search yielded no 2018-2019 Ivy League course that focused on honor-based violence, including honor killing, female genital mutilation, forced veiling, child marriage, polygamy, “Eve teasing” (a south Asian euphemism for sexual harassment), or rape as a weapon, not merely a spoil of war.

Our Second Wave plain-spoken analyses have become neutralized by incomprehensible, jargon-clotted treatises that rail against objective reality and Western civilization and refuse to consider that other tribal, patriarchal cultures may actually be more misogynistic than our own.

Radical feminism has been hijacked.

Celebrity feminists oppose racism, imperialism, colonialism, historic slavery, climate apocalypse and support gay, queer, and transgender rights. Fine—but everyday sexism has been rendered less important; motherhood—forgotten; abortion rights—lip service only, little activism; domestic violence (male on female), and women’s economic inequality, minimally mentioned.

Much of the Ivy League gender and sexuality curriculum is based on writings from the 1990s and the 21st century, nothing earlier. (Exceptions to this trend are mainly found at state and city colleges.)

The academy absolutely had to expand beyond the white male Western canon but oh, how far the pendulum has swung. The most prestigious universities now offer feminist courses titled “Transgender Cultural Studies” (Stanford); “Sexual Minorities From Plato to the Enlightenment” (Yale); and “Queer Theology” (Harvard).

Now is the time to create an intellectually and politically diverse feminist canon, one that begins with the work of our foremothers and forefathers. Otherwise, women’s studies, as well as the humanities, liberal arts, and social sciences, are lost. Racism is sickeningly real. However, the obsession with racial victimization and the desire to atone for historical slavery have chased all reason away.

First published in Real Clear Politics.