Pearl Harbor Myths

by Marc Epstein

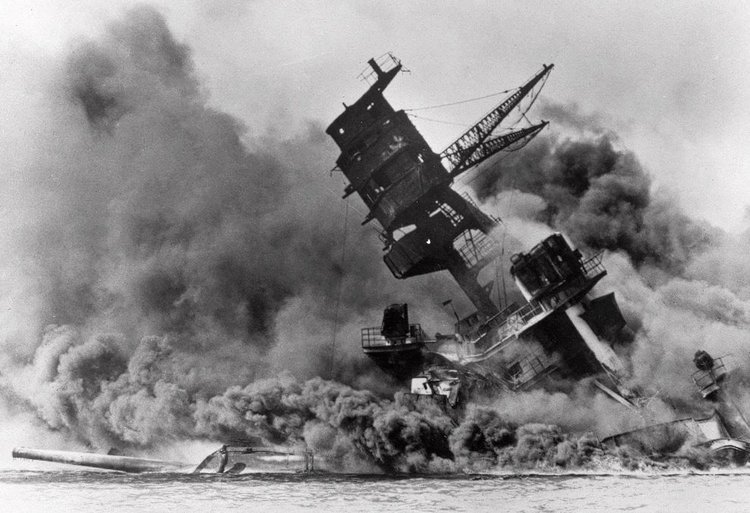

December 7, 2003 — WITH the passage of time, the attack on Pearl Harbor had begun to fade from memory. But 9/11 changed all that; how could it not?

The comparisons were irresistible. In both instances airplanes descending out of the skies caught America unprepared, inflicting enormous damage to life, property, and the national psyche. A headline declared “Another Pearl Harbor, truly.”

It wasn’t long before the conspiracy theories began to circulate, along with charges that President Bush knew what was coming before it happened – just as past theories had said of FDR.

But the received wisdom that Pearl Harbor was an American intelligence failure has it backwards. The real failure was on the Japanese side, not ours.

For Japan to succeed in knocking the United States out of a Pacific war, Hawaii had to be rendered useless as an American base. Whatever was left of Adm. Kimmel’s Pacific fleet had to be forced back to California, leaving Hawaii undefended.

The attack failed of that goal, because Adm. Nagumo declined to risk a third wave of attack runs from his carriers. Why? Because Japanese intelligence had wrongly determined that that three American carriers were in Hawaiian waters.

In fact, we had only two, USS Enterprise and USS Lexington. And because both had put to sea days before the attack, even Japan’s spies in Hawaii could not definitively inform the attacking armada that the estimate was high.

By the time the second wave of attacks on Pearl Harbor was over, U.S. anti-aircraft fire had knocked down close to three dozen planes. Our defenses, which had at first been caught off guard, became increasingly more effective as the attack wore on.

Nagumo, who unlike our carrier commanders had no flight experience, decided to play it safe. To protect his fleet against a counterattack by the three U.S. carriers he thought he might face, he’d need all his remaining planes. A third strike would be too risky.

As a result, our naval fuel-oil tanks remained intact – and Pearl remained a viable base for the fleet. The salvage and re-floating of most the ships at the bottom of the harbor proceeded apace.

In June of 1942, just six months after Pearl Harbor, American carrier-based aircraft put four of the Japanese aircraft carriers that had carried out the Dec. 7 attack on the bottom of the Pacific. By that time, American naval intelligence was decoding Japanese naval transmissions, making the stunning victory at Midway possible.

While the shock effect and loss of life sustained at Pearl Harbor should not be underestimated or trivialized, it was a very short-term victory for Japan.

Other popular myths still surround that attack. In fact, it didn’t take the sinking of 21 warships at anchorage to convince U.S. naval planners of the power and use of the aircraft carrier. Despite the shrunken military budgets of the isolationist ’30s, American carrier R&D had continued to advance.

Our carrier tactics were the equal of Japan’s, with the use of aircraft carriers as the primary strike weapon already executed in war games directed at the Panama Canal in the 1930s. In fact, navy planners had assumed war with Japan was inevitable back in the 1920s, and assembled a fleet that was tailored to that eventuality.

Unlike 9/11, Pearl Harbor represented an administrative failure to get the right information to the right people at the right time. Our intelligence in Washington knew the Japanese were about to start a war, but a Byzantine military structure unsuited to timely action failed to get the word out.

__________________________________

Marc Epstein is a historian specializing in Japanese-American naval disarmament between the wars.

Originally published in the New York Post in 2003.