Putin’s wishes v. Putin’s abilities

by Lev Tsitrin

“My great-grandfather said: ‘I’d love to buy a house, but I can’t. I can buy a goat, but I don’t want to.’ So let’s drink to our wishes matching our abilities!”

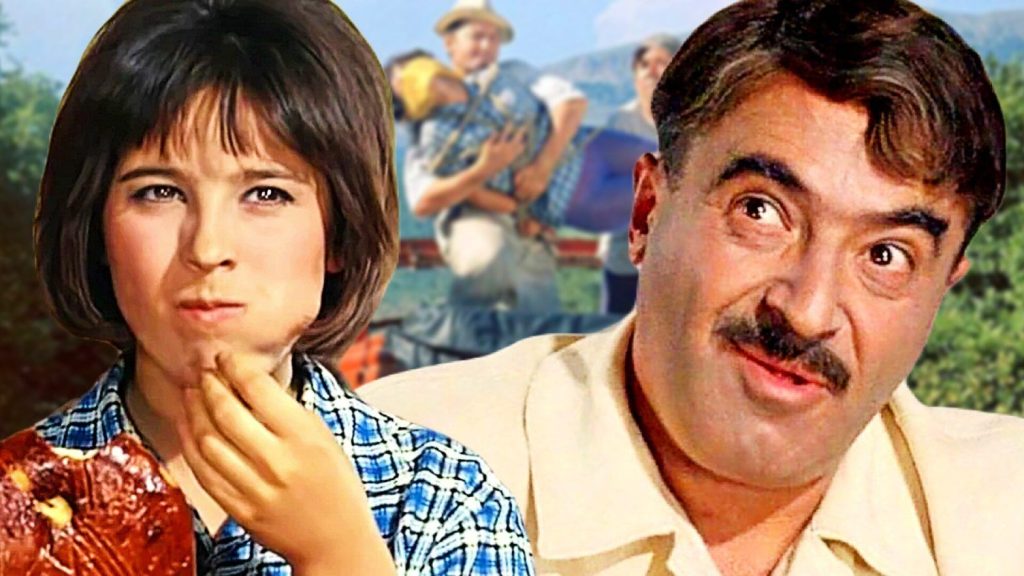

In a much-beloved 1967 Soviet comedy titled “The She-prisoner of the Caucasus” (the title is a highly irreverent parody on that of Tolstoy’s almost eponymous, tragic story “The Prisoner of the Caucasus;” yet the hilarious feminist plot of the movie has nothing whatsoever to do with Tolstoy), this was the first toast offered to Shurik, an ethnologist on a hunt for legends, tales, customs and toasts of the Caucasus mountains.

My first thought on hearing it was, “wouldn’t it make much more sense to have it the other way around, to wish that our abilities matched our wishes? Wouldn’t that be much, much nicer?” Only later did I realize that the film’s version was indeed far wiser than mine: human desires are open-ended, and to wish for abilities to fulfill them is a height of folly.

But suppose one heads a rich and powerful state — what then? His resources, both material and human, are vast. Can’t at least he have anything he wants?

We are about to find out. Mr. Putin, as is well known for at least half a year, wants Ukraine. So far, however, the rule of mismatch between abilities and wishes is holding pretty firm. While Mr. Putin managed to pocket some twenty percent of Ukraine, what he’s got is in ruins, and his gains are fiercely contested by Ukrainians. (That the costs in human life are huge does not matter to him, of course — his kids are not fighting on the front lines; the grief is left for others to feel, while Mr. Putin just basks in heroic glory.)

This return on invested abilities being, so far, relatively and unexpectedly meager, Mr. Putin decided not to adjust his wishes to his abilities, but to increase his abilities: “Putin Orders a Sharp Expansion of Russia’s Hard-Hit Armed Forces,” per the New York Times‘ headline. He ordered a 10% increase in the size of the Russian armed forces, “by about 137,000, to 1.15 million,”

It may help; yet Mr. Putin’s problem is that Ukrainians also have their own set of wishes, and their own abilities — filled by the US and NATO — which they strive mightily to increase. Wishing is not a one-way street; increasing the ability to fight is the prime goal of Ukrainians, too — and they are not without their successes.

And so, we have a battle of abilities that support well-known desires: Mr. Putin’s to conquer Ukraine, and that of Ukrainians to not be conquered. Whoever exhausts their abilities first, will have to switch to adjusting their wishes to abilities. Clearly, Mr. Putin, counting on Russia’s huge predominance in resources, thinks that he will force Ukrainians to bite the bullet. And yet, this war is full of surprises, so who knows whether it won’t go the other way?

If either Ukrainians or Russians read this, and they wish to watch the philosophical toast (though all toasts are exercises in philosophy, of course), it is at 6:40 of the movie. And even those who don’t know Russian may still watch the movie just for the fun of it (you can read Wikipedia’s perhaps over-detailed description of the plot first) — the movie is redolent of sun, beauty and youthful energy, and as such is a very welcome break at the time of war (or if you are a Russian citizen obligated to follow Kremlin’s vocabulary, of the “special military operation.”) Of course, unlike the phrasing of the toast, it does not matter how you call the butchery that goes on in Ukraine. What matters is, that it ends soon, that Putin’s ability for empire-building is heavily trimmed, and just as the toast suggest, that he be forced to adjust his wishes to those much-reduced abilities, focusing on the well-being of Russian people instead of on expanding Russia’s borders.