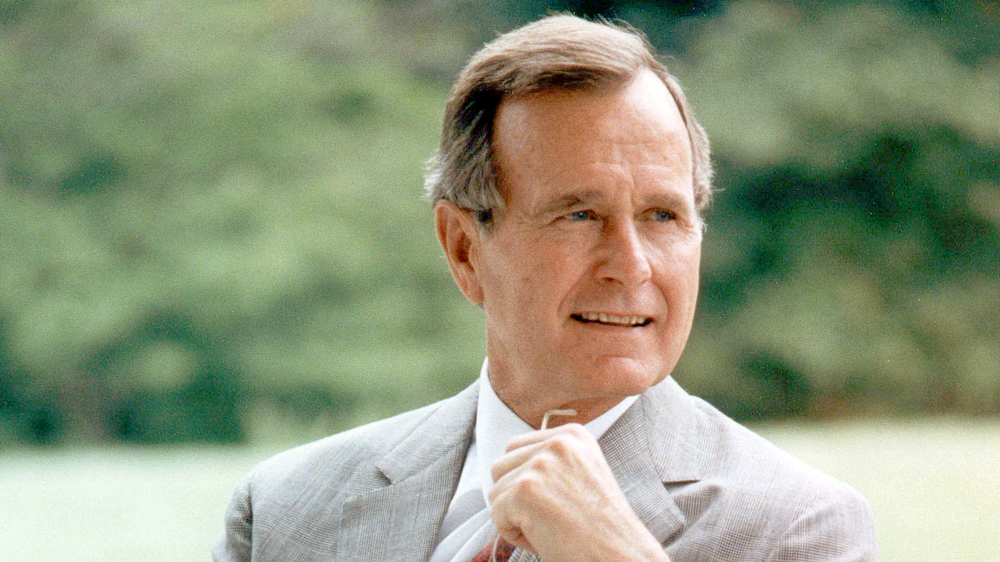

The Man Who Got Along

George H. W. Bush was a decent, honorable, and admirable man but not a distinguished political leader.

by Conrad Black

George H. W. Bush did, as many have stated, exemplify the highest civic and human virtues. A political or historical evaluation of him will be more complicated and, necessarily, somewhat less laudatory.

No one should be discredited because of good fortune. The late president’s father, Senator Prescott Bush of Connecticut, had married the daughter of a close associate of a longtime prominent Democrat, railway heir, governor of New York, and ambassador to the Soviet Union and United Kingdom, Averell Harriman, and of Secretary of Defense Robert Lovett. Prescott Bush, whom Richard Nixon knew well in the Senate and always reckoned “the smartest of all the Bushes,” was a liberal Eisenhower Republican who had to fight his way to election past Abraham Ribicoff and Thomas Dodd. His son George, after brave and decorated service as a WWII naval aviator in his late teens and then graduation from Yale, showed great enterprise in decamping with his young and redoubtable wife Barbara (a descendant of President Franklin Pierce) from New England to Texas, where he used his father’s connections to set up successfully in the oil industry.

There were practically no Republicans in Texas at this time, and the state was run with a strong but reasonably benign hand by the masters of Congress, long-serving House speaker Sam Rayburn and the Senate majority leader, Lyndon Johnson. Between them, in one capacity or another, they served Texas in Washington for 80 years, including 19 years as speaker, 14 years as Senate majority leader, vice president, and president, and six years as a congressional minority leader. One or the other or both were among the three or four most powerful men in Washington for over 30 years.

George H. W. Bush, as he prospered in Texas, gathered together some kindred spirits and started to construct a Republican party in the state. This too, like entering the Navy before going through college, and like striking out for Texas, showed great enterprise, and in 1964 he ran against incumbent U.S. senator Ralph Yarborough in the teeth of the mighty landslide racked up by Lyndon Johnson in the presidential race. Johnson defeated Barry Goldwater by 905,000 votes in Texas while Bush, running as a conservative and opposing Johnson’s civil-rights reforms, lost to Yarborough by only about 330,000 votes, a commendable performance that was noticed by party elders. Bush then gained nomination in a promising and prosperous New South suburb of Houston and was elected its congressman in a strong Republican year, 1966, and reelected in 1968.

President Nixon persuaded him to give up his congressional seat in 1970 to run again for the Senate, but Yarborough lost the Democratic primary to a more conservative former congressman, Lloyd Bentsen, which meant Bush was running as the liberal and would trim his sails accordingly (not for the last time in policy matters). John Kenneth Galbraith, the quasi-socialist Harvard academic, urged Texas (where there cannot have been more than a few hundred people who would pay any attention to his political views) to vote for Bush. Bush lost by only about 130,000 votes. But from here on, his career depended on others. Nixon remembered his sacrifice and appointed him ambassador to the United Nations, and then Republican-party chairman, in what proved a very difficult time, as the Watergate debacle engulfed the administration.

Bush did a respectable job of defending the president, his benefactor, for a time, but then he swiveled (reflecting, he said, his duties as party chairman) and semi-privately urged Nixon’s resignation. His position was defensible but not especially distinguished. Nixon bungled the issue, but that does not erase the fact that the second special prosecutor, Leon Jaworski, and his rabidly anti-Nixon staff mistakenly concluded that Nixon had authorized hush money for the Watergate defendants. There was and is no such proof, but everyone except his family and Pat Buchanan and a few others deserted the president. Bush was in numerous company, but he could have done better.

President Gerald Ford, a former congressional colleague, rewarded Bush for his services during the Watergate end-game by offering him a number of positions, and Bush chose to be representative to China, and then director of central intelligence. George H. W. Bush was deemed to have handled all of these positions competently, and in 1979 he ran for president as the party-establishment, Ford-Rockefeller-moderate alternative to Ronald Reagan. But he had nothing like the political base of Reagan, a two-term former governor of California, the torch-bearer of a new spirit of capitalist and post-Vietnam conservative optimism and an almost hypnotic public speaker.

Because Bush ran a distant second and withdrew from a primary that he would win after Reagan had clinched the nomination, Reagan, without any strong feelings about it, gave him the vice-presidential nomination. Bush served with perfect loyalty and an eye to succession, and defeated Robert Dole for the nomination to succeed Reagan. The outgoing president’s coattails and Bush’s bare-knuckles political manager Lee Atwater, who produced a hardball campaign against the ineffectual Democratic nominee, Massachusetts governor Michael Dukakis, won the election. George Bush hadn’t really faced an electorate on his own successfully since 1968, and he did not bring a huge following behind him the way Roosevelt, Eisenhower, Kennedy, Nixon, and Reagan (and later Obama and Trump) did when they were elected.

Apart from the brilliantly organized and executed campaign to evict Iraq’s Saddam Hussein from Kuwait, and his exquisite diplomacy and lack of triumphalism at the end of the Cold War and the disintegration of the USSR, his term was indistinct. Bush had promised “no new taxes — read my lips.” After a year, this had become “read my hips” as he jogged past news cameras. The people did not forget. He had said he wished to be known as “the education president” and “the environment president,” and he was surely sincere, but he didn’t do anything to earn those labels. He and James Baker had no business urging confederal virtues on Ukraine and Yugoslavia (and were not heeded anyway). When the Reagan boom finally settled, his economic message at the beginning of 1992 was to go out and spend more, even borrowed money.

He and his official entourage — Dan Quayle, James Baker, Dick Cheney, Bob Mosbacher, Dick Thornburgh, Robert Gates, Nick Brady, all good and principled men and a couple of them exceptionally able — were socioeconomic look-alikes. The administration wasn’t particularly rooted in a great national constituency or a skillfully constructed coalition of factions, regions, or interests. It was fluid in policy terms, faced a solid Democratic Congress, and never really took hold with the public, other than in the Iraq War. Bush’s awkward prose led to a good deal of embarrassment. It is almost impossible to believe now, but George Bush allowed his party to be divided and sandbagged by the charlatan billionaire Ross Perot, who won 20 million (mainly Republican) votes in 1992. Bush’s limitations as a political chief cost him reelection and brought the Clintons down on the country — not a terrible fate, but an easily avoidable one. He was not so much a dynast as the first president in 200 years who had sons capable of fulfilling high political ambitions.

Richard Nixon thought George H. W. Bush “a good man with good intentions . . . but no discernible pattern of political principle . . . no political rhythm, no conservative cadence, and not enough charismatic style to compensate.” And part of the bipartisan praise of him that we are hearing now is because Democrats love Republican leaders they can defeat, as we recently saw with John McCain, and their hatred of Trump propels them to canonize a preceding president who was such a decent man. Personally, he was unfailingly gracious, modest, and likeable. James Baker reckons the late President Bush the country’s best one-term president. I would give that honor to Nixon (using an elastic definition of “one-term”), followed by James K. Polk, with Mr. Bush contending honorably with John Adams.

With all that said, not every president is a Lincoln or Washington or Roosevelt (of either party). And the president the nation now mourns was a fine and admirable man and leader, a brave patriot, and a great gentleman. Service was his honor and his vocation, in peace and war (and he is the last president who served in combat). He deserves every word and gesture of admiration he receives this week.

First published in National Review Online.