The March of Time, Washington and Paris

by Michael Curtis

Paris 1968

“Everywhere I hear the sound of marchin’, charging feet, cause summer’s here and the time is right for fighting in the street.” The words were written in 1968 by Mick Jagger who said he wrote it after an anti-war rally at the U.S. Embassy in London, and he was inspired by the student rioters in Paris in May 1968. At that time protests in various countries of Europe, in the U.S., in Mexico City, in Brazil, were directed against the Vietnam war, but the most spectacular events, the May Days in Paris, sprang from the student led protest movement that began on March 22, 1968 as an anti-war rally at Nanterre University, and became a revolt against the political and academic establishment.

It is tempting to compare those events on its fiftieth anniversary with the remarkable youth organized demonstrations, the March of Our Lives, on March 24, 2018 protesting against gun violence, in Washington, D.C. and elsewhere in the U.S., resulting from the murder of students on February 14, 2018 at the Marjory Stoneman Douglas high school in Parkland, Florida where 17 were killed by a teenage gunman. The D.C. march attracted an estimated crowd of 800,000 youngsters and supporters, and was accompanied or financed by celebrities such as George and Amal Clooney, Oprah Winfrey, Stephen Spielberg, the Gucci group, pop artists and performers.

In his address on March 25, 2018 at the Palm Sunday service in St. Peter’s Square, Pope Francis, without specifically alluding to the Washington demonstration, urged young people not to let themselves be manipulated. “Young people,” he directed, “you have it in you to shout. It’s up to you not to keep quiet.” Certainly, young people in 2018 had done this as they had in May 1968.

Since the writings of Polybius, the Greek historian of the Hellenistic period, the question has been discussed of history as repeating a cycle of events, of regular patterns, of people animated by the same desires and passions. Youth in 2018 and 1968 have expressed those qualities, displaying energy, and a spirit of resistance and defiance, even quasi-revolt. Yet, even admitting that history can be seen as a sequence of causes and effects the two events show we are not doomed to repeat the past.

Both events, 1968 and 2018, began with a particular incident: one, the university administrative actions against student activists at Nanterre University, the new campus in the suburb of Paris; the other the Parkland massacre. Both called for change of some kind, university or more broadly social. Both can be regarded as nation-wide movements.

But there are important differences. May 1968 was concerned at first with a specific issue, rigidity in the hierarchy of the French University, with students wanting more political freedom since political meetings were normally forbidden. However, it became transmuted into a wider more disjointed affair, including calls for overthrow of institutions; 2018, at least so far, is pinpointed at a concrete, single purpose.

The 1968 events had started as the result of a specific action, the detention of student in the anti-war rally, but with provocative slogans, and spreading to the main Sorbonne and other Paris educational units, it transformed itself into a revolt against established institutions, advancing social changes, and protests against capitalism and U.S. imperialism.

May 68 exhibited ideological confusion indicating different left wing political orientations, as well bizarre slogans “imagination in the leadership,” and “demand the impossible.” In contrast, 2018 is not partisan or ideologically expressed in any real way. Students in France in May 68 were joined by support from factory workers who organized a general strike, the largest in France, and 11 million workers who occupied factories went on strike. No similar action has been contemplated in support of 2018. In May 68, word spread in the streets, while in 2018 social media spread the word in an instant, and the whole world is aware of the issue. Above all, May 68 quickly became violent; March 2018 has been noisy but non-violent.

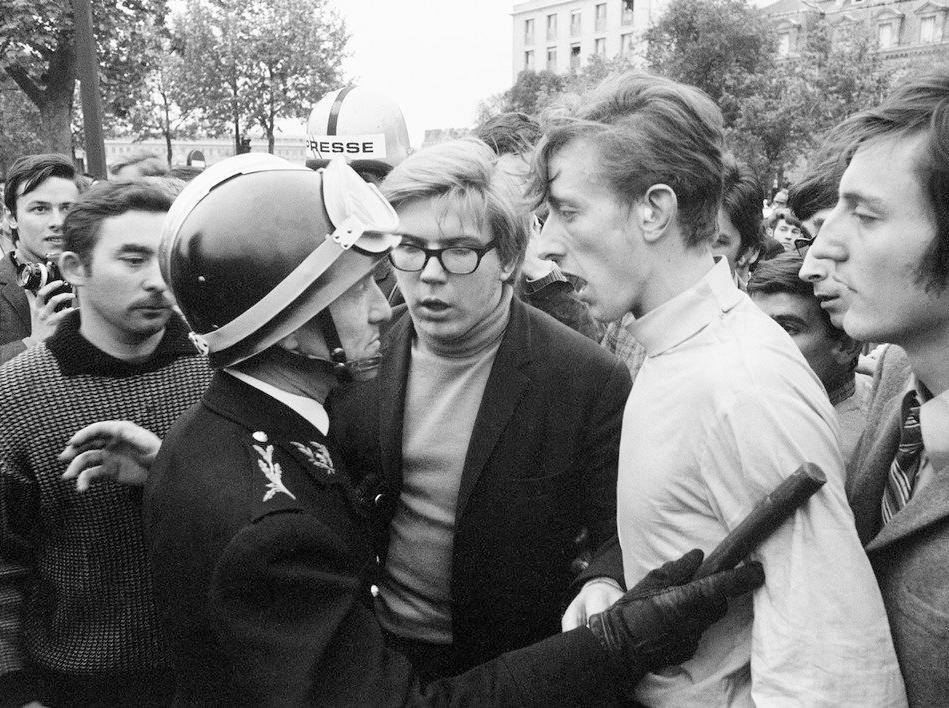

In May 68, universities and factories were occupied throughout France. Paris was the scene of cobble stones being torn up in the pavements, barricades, street fighting with the police, cars overturned, and stores looted. At one point the turmoil and threats seemed so serious that President Charles de Gaulle on May 29 fled the country, for a day, to go to a French military base near Baden Baden in Germany.

The protest of May 68 was violent but became mixed or even incoherent with the infighting among the student groups, Trotskyists, Maoists, anarchists, surrealists, moderate Socialists. It was not a unified or cohesive group but a number of individual personalities among the various improvised leftists fighting among themselves, even if some vague concept of anti-imperialism emerged. They had no coherent program or structure, but claimed to act in “uncontrollable spontaneity” that gave them impetus without it being canalized. Jean Paul Sartre was impressed with this, with the attempt, as he said, to implement imagination into reality.

Others were more critical. Raymond Aron saw the student participants as actors imitating the French revolutionary past, a kind of “psychodrama,” and merely acting in a rehearsal held almost two centuries after the play had been staged. The students were actors imitating the figures of the 18th century French Revolution. Indeed, some student protagonists labelled themselves as Les Enrages, not a unified party but the radical extremists who opposed the Jacobins in June 1793, and who spoke on behalf of the poor.

In May 68 some leaders emerged, the most well-known being Daniel Cohn-Bendit, nicknamed “Danny the Red,” because of the color of his hair. Born in France of German parents. a philosophy student at Nanterre, an anarchist if he can be classified, he inspired the movement with his captivating oratory, courage and humor. So far, no single similar figure has emerged in 2018 as similarly inspiring, though some 17 year olds have been eloquent, and expressed rhetoric that has gone beyond the single issue of controlling guns. One speaker went beyond the manifest purpose of the March, not openly by demanding more general social change, and getting rid of politicians, but also by enthusiastically giving the black power salute at the end of his peroration.

May 68 did lead to some social and political changes, including raising minimum wages. It also led to President de Gaulle calling a referendum on April 27, 1969 on government decentralization and for changes in the French Senate. It was rejected by 52% of the voters, and de Gaulle resigned the presidency the next day. It remains to be seen if there will be similar political consequences of the March of Our Lives.