Tattoo art is becoming alarmingly skilled and prevalent. What does its ascent from the marginalised to the middle classes signify?

by Theodore Dalrymple

When I started as a prison doctor in 1990, I was both fascinated and horrified by the tattoos inscribed on the skins of the prisoners. The prevalence of tattooing among prisoners was something upon which Lombroso, the Italian doctor, anthropologist and criminologist, had remarked more than a century previously, and I should dearly have loved to have produced a book, The Tattoos of England, had I been able to introduce a camera into the prison. I even propounded a spoof scientific theory that criminality was caused by a slow-acting virus introduced by the tattooing needle, which someone went to the trouble of refuting as if it were intended seriously.

The prisoners’ tattoos were mainly crude, the product of cottage industry as it were, with messages such as “Made in Britain” round a nipple, or a dotted line with “Cut here” round a wrist. One man had been attacked several times in pubs because of the words “No fear” tattooed on the side of his neck. Another had a policeman hanging from a lamp-post on the inside of his forearm.

‘That must do you a lot of good down the station,” I said.

The letters “ACAB” tattooed on the knuckles could mean either All Coppers Are Bastards or Always Carry A Bible, depending on context (criminals were the first post-modernists). When the letters LTFC and ESUK tattooed on the knuckles were conjoined, they read LETS FUCK: and, according to those whom I asked about thus, the invitation sometimes worked in a pub when the bearer approached a woman there, at least often enough to make having the tattoo worthwhile.

In those days, the prison, anxious to do something positive for the prisoners, offered a tattoo-removal service, since it was difficult to find employment with an antisocial message inscribed on one’s forehead or other prominent part. But removal was possible only on a small scale: nothing much could be done for those who had, for example, a spider’s web tattooed all over their face and often their scalp. Another interesting phenomenon was the blue borstal spot over a cheekbone that was the equivalent of the old school tie. Quite a number of my younger patients in the hospital next door to the prison tattooed themselves with this spot even though they had never been to borstal but wanted to look as if they had been, since a reputation for, or appearance of, toughness was the best form locally of defence.

But I noticed that the tattoos began to change in type. Where once they were simple and amateurish designs in India ink, they were now more elaborate—tattoos of many colours. First came hearts in red surrounded by green foliage, with the names of girlfriends or wives written across them, sometimes with their names crossed through once the loved one had become the hated one. Fathers came to think that tattooing the names of their children on their arms was the highest manifestation of parental concern.

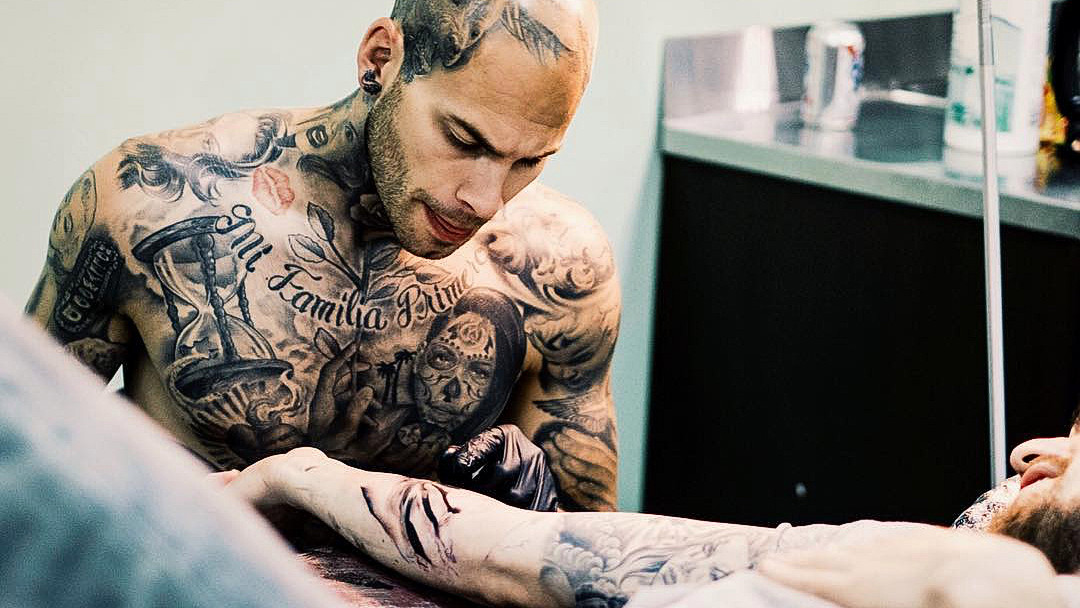

It was obvious that tattooing was undergoing a change: it was becoming professional and increasingly skilled. The increasing skill of it appalled me, for what should not be done at all is all the worse for being done well. Skilled tastelessness and kitsch is worse than botched tastelessness and kitsch. But even more alarming to me was the spread upwards on the social scale that I noticed, I think earlier than many people.

Whereas tattooing was once the province of the sailor, the marginalised, the criminal and the odd degenerate of the upper classes, it was fast becoming fashionable in the middle classes. In the early Sixties, I used to love to go to Speakers’ Corner, where (among the fanatics and the religious missionaries, including an evangelical atheist) there was a man tattooed from head to foot who did not speak at all but simply took off his clothes to reveal his tattooed body, to the accompaniment of the oohs and aahs of the amazed audience—or that part of it that had never seen him before, or anyone like him. But now such a man would not be regarded as the freak that he seemed then, but rather, at worst, as a weak-minded follower or acolyte of David Beckham, or more likely as perfectly normal person merely expressing himself.

What did the ascension of tattooing up the social scale mean or signify? When the ascent was still in its infancy, as it were, I interpreted it as an attempt by middle-class persons of intellectual disposition to demonstrate their affinity with and sympathy for the marginalised, thereby demonstrating their political virtue. If imitation is the highest form of flattery, it is also imagined to be empathic, and in our otherwise relativist times there is no virtue as great as empathy.

I reviewed the book Bodies of Inscription: A Cultural History of the Modern Tattoo Community, published in 2000 by an academic press, written by a cultural anthropologist, Margo DeMello. She drew my attention to, among other things, the fact that young academics were getting themselves tattooed. I began to notice junior doctors with tattoos, usually discreet and visible only when they bent over or otherwise accidentally revealed some small portion of their flesh. Policemen were tattooed, immigration officers, no doubt politicians too: certainly the wife of one recent Prime Minister. A friend of mine went to Uppsala University to deliver a lecture there and noticed (it being a warm summer’s day on which people revealed more of their flesh than usual) that practically every male student was tattooed.

Certainly, statistics bear this out. At least a third of men under the age of 40 in Britain and America are now tattooed and, with the cultural masculinisation of women, an increasing proportion of women, too. The type of person who would once never have dreamed of getting a tattoo, the thought of which would never have entered his or her head for a fraction of an instant, is now frequently joining what DeMello called “the modern tattoo community”. Of my 12 middle-class French nieces and nephews, at least five are tattooed, one of them heavily: and, until the last 15 years or so, the French were much less inclined than the British to have themselves tattooed. Indeed, until quite recently, no member of my family, no friend of my family, no family member of a friend of my family, was tattooed. It has all happened quite suddenly.

An article in the French newspaper Libération not long ago claimed that the number of professional tattooists in France had increased from 400 in 2000 to 4,000 ten years later. France being France, the tattoo “artists” apparently wanted the government to give them an officially-recognised status and statute: in other words, they wanted to be regulated. On the other hand, the names of their studios, often in English, the language of, among other things, international abominable taste—Evil in the Ink, for example—suggested a kind of emotional antinomianism.

The article was published on the occasion of a tattoo fair held in a large former market hall in Paris. Entry was not cheap at 30 euros, and apparently 30,000 people attended, mainly young of course. The latest technology was on display. There was a time when a full sleeve, a tattoo that covers an entire arm, would have taken many sessions of work by the tattooist and have been very painful, indicating a kind of devotion to a cause. (Devotion to a cause is by no means always an admirable quality.) But these days, thanks to technological advance and moral and aesthetic regress, large areas of the skin can be covered in a matter of a couple of hours, moreover using colours such as bright lemon yellow that were once unknown to tattooists.

At the end of each day of the fair, there was a contest to choose the most “beautiful” tattoo done that day. About a score of people, mostly young women, and mostly very pretty, competed for the title. Whereas previously my predominant emotions had been disdain and even disgust, I was suddenly seized by sorrow and pity. Why were people, by no means stupid, uneducated or deformed, doing this to themselves?

Even if tattooing is now so common that it can be considered normal in the statistical sense, as once it was not, it retains a faint connotation of rebellion or revolt, at least for those who cannot be considered marginal themselves and would therefore not have had themselves tattooed. They think that by having themselves tattooed they are shocking the bourgeoisie à la Baudelaire; and in so far as their parents don’t like it, and are in effect silencing them by a fait accompli of which it is useless for them to complain, they are exercising power over them.

However, at the same time as the tattooed think that they are rebelling, they are joining what DeMello called a “community”. (More recently, in what is no doubt a manifestation of the desire to fit in with the majority, even dark-skinned minorities, whose epidermis is unsuited to tattooing, are having themselves tattooed in ever-larger numbers.)

DeMello’s use of the word community is telling in itself. In an increasingly atomised society (such that flats are now commonly constructed in which there is nowhere for people to eat together), any commonality between people—such as having a tattoo—is said to create a “community”. A butterfly on a buttock gives one something important in common with someone who has a skull tattooed on his shoulder. By this standard of community, I am a member of the anchovy-on-toast community, among many other communities.

As all good things come in threes—Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité or Travail, Famille, Patrie, for example—in addition to rebellion and community, tattoos confer, at least in the eyes of those who have them, the quality of individuality: thus Rebellion, Community, Identity.

Tattooed people think they are expressing themselves by inscribing some symbol or other on their skins: although, of course, the iconography of tattoos is very limited. Strangely enough, much of it resembles the art work of prisoners when, with time on their hands, they begin to draw and paint. It is true that some people have a photographic portrait of Einstein or Elvis Presley tattooed on their back with a skilful realism that I find chilling; but for the most part, the designs are very limited in variety.

It seems obvious to me that if a person feels he has to tattoo himself in order to “express” his difference from others, he must have some difficulty in individuating himself, perhaps indicative (when this difficulty is on a mass scale, as it clearly is) of an individualistic society without individuals.

What has also struck me about this modern fashion (which goes along with that for self-mutilation by piercing) is that it is almost free of any kind of criticism: on the contrary, there is an almost obsequious acceptance of it, as if to say that you found it aesthetically hideous and deeply savage were to declare yourself an Enemy of the People. Famous persons tattoo themselves and appear in advertisements: it would be lèse-celebrité to comment unfavourably on it.

What of the future of tattooing? Will the fashion pass as, say, the fashion for kipper ties passed, or will it persist? One thing that might keep it going is the fact that, were it to pass, those who had had themselves tattooed would feel themselves humiliated by the contempt in which the untattooed who were younger than they might begin to hold them: for there is only one thing more pitiful than a tattoo on young skin, and that is a tattoo on old skin. Therefore the tattooed have a vested interest in ensuring that the fashion continue, and will even become evangelical on its behalf. They are in ink stepped in so far that, should they wade no more, returning were as tedious as go o’er.

First published in Standpoint.

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

3 Responses

Just now told Barb that I might have a specific part tattooed with E=mc2. She pretended to not hear.

There is something pitiful, even masochistic, in getting a tattoo. Yes, a tattoo doesn’t age well as the firm young palette sags. I can’t help but associate tattoos with the ID numbers tattooed on concentration camp inmates.

Tattooing is against Halacha (Jewish law) as it is considered a marring of the body, which is the property of Hashem (God), and not one’s own to mess with.

Aside from that, it is a patently superficial way to express one’s individuality, which should instead involve learning and inner convictions. For example, the world is a better place thanks to Aristotle, who tended to be unkempt because his preoccupation with ideas left little time for appearances, or tattoos.