The U.S. Senate and the Problem of Bias

by Michael Curtis

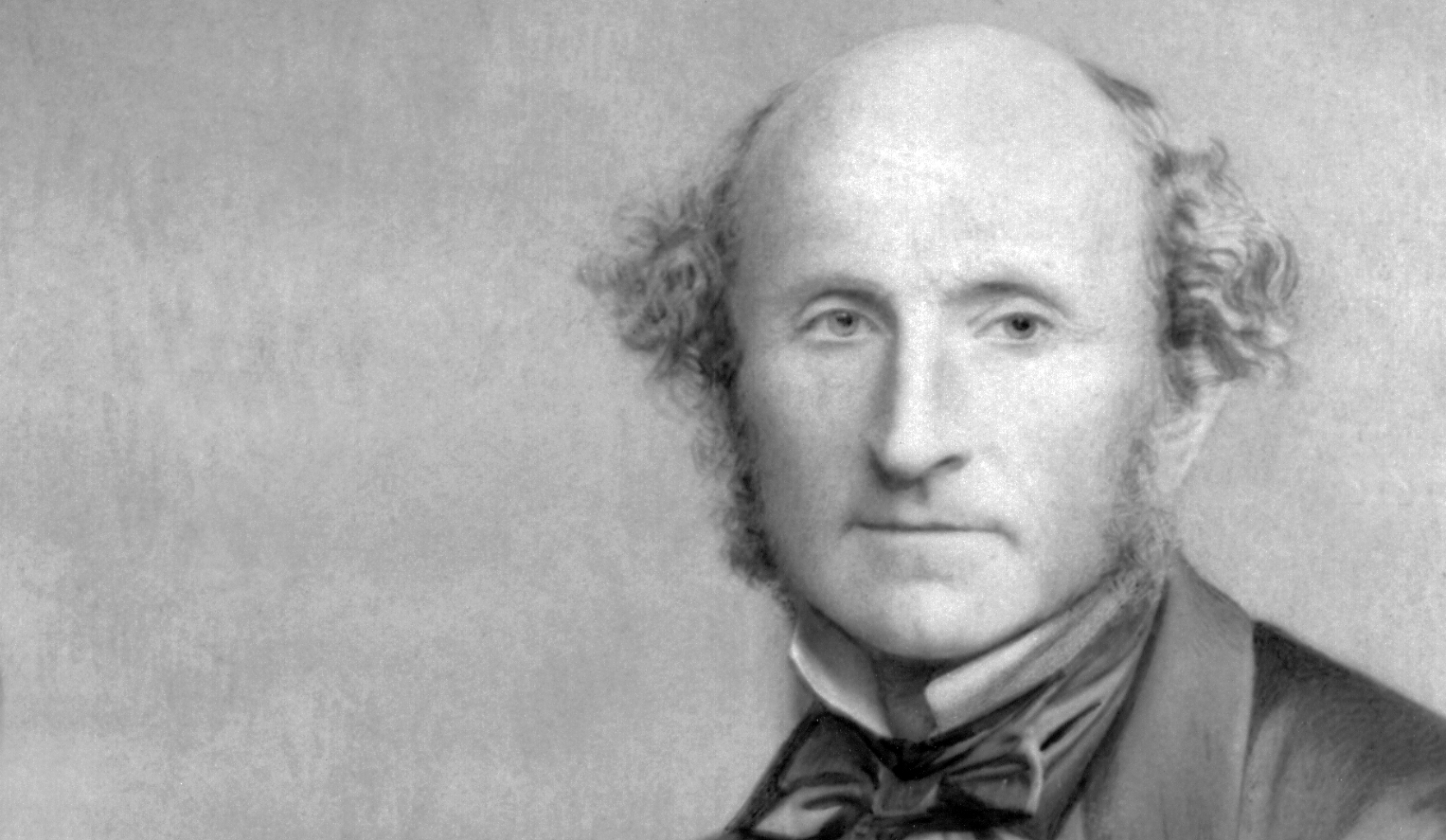

John Stuart Mill

Beware, lest we walk into a well from looking at the stars.

In politics, John Stuart Mill told us, it is almost a commonplace that a party of order and stability, and party of progress or reform, are both necessary elements of a healthy state of political life. Only through diversity of opinion is there chance of fair play to all sides of the truth. It is not the violent conflict between parts of the truth, but the quiet suppression of it that is the formidable evil. Mill’s wisdom is pertinent to two aspects of contemporary American culture: the censorship of opinions by the social media giants; and the inherent bias, left wing slant, of much of the U.S. media.

A warning of the present intolerant climate in culture has been issued by the 153 intellectuals and artists who signed the letter on justice and open debate published by Harper’s Magazine on July 7, 2020. The authors were concerned that the free exchange of information and ideas, the lifeblood of a liberal society, was daily becoming more constricted. It warned of a new set of moral attitudes and political commitments that tend to weaken our norms of open debate and toleration of differences in favor of ideological conformity.

A similar warning statement was made on July 12, 2020 by journalist Bari Weiss, who describes herself as “center left” on most things. In resigning as a New York Times opinion editor, she wrote, “a new consensus has emerged in the press, but especially in the NYT that truth isn’t a process of collective discovery, but an orthodoxy already known to an enlightened few whose job it is to inform everyone else.”

Recent events, especially those connected with the rhetoric and activities of President Donald Trump, have shown that an “enlightened few,” in a small number of unelected, unaccountable companies have acted to control the norms of open debate and part of the global public conversation, on the Internet, and perhaps thereby embitter political debate. No one has given authority to Mark Zuckerberg, Jack Dorsey, or Jeff Bezos to decide what conversation online is permissible to be published in the U.S. public space. Nevertheless, on January 6, 2021 Twitter suspended the account of Donald Trump, and a day later, Facebook, and then Twitter, issued an indefinite suspension and a permanent ban on messages by Trump. They cite their rules forbidding content that incites violence. At the same time, Google and Apple removed Parler, a small social network with ten million, popular with political conservative and far right individuals from its stores, and Amazon eliminated Parler, which broadcasts parleys, from its cloud service, its hosting service.

Understanding that these actions were taken in response to the justifiable outrage over the events of January 6, 2021 when a violent mob marched in Washington, D.C., and stormed the Capitol, and that no company wants to be linked with the kind of posts associated with that mob, it is arguable whether the censorship by the Big Tec giants has gone far beyond what is desirable in a democratic society where diversity of opinion is intended to ensure fair play. The U.S. which has always favored an open internet is now confronted with the problem of sustaining a free and open global internet.

The Big Tech giants, particularly Facebook with 2.7 billion followers, and Twitter, with 300 million, are private companies and are free to decide what they should publish and reject. They are protected by Section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act that shielded companies from liability for what users post on their platforms. It wanted to make sure that new companies were not handicapped by requirement to monitor large amounts of information they could not handle. Section 230 promoted the continued development of the internet and other interactive media, and preserved the competitive free market for the internet unfettered by federal or state regulation. Companies can remove posts without assuming legal liability. Those companies devise their own rules, can post content and remove content they see as objectionable while not being liable for what is posted by third parties.

Many people approve the removing of Trump from the media platforms, basing this on their argument that his online posts might lead to further violence by his supporters. The problem is that there will probably never be consensus over arguments of this kind and the decisions of Big Tech. For a heathy political system there should be conversation over the standards proposed by Big Tech for censorship of expression and over its definition of what constitutes inciting violence.

That concentration should deal with two issues. One is the wisdom of a concentration of power over expression in the hands of Big Tech. The other is the degree of political bias in favor of those whose views are acceptable. This was noticeable in the lack of news or refusal by Big Tech to report on the allegations against Hunter Biden before the presidential elections, or on the tweets by the Iranian ayatollah for armed resistance against Israel. Critics have also pointed out that Big Tech in spite of its apparent incitement published the statement of activist against racial inequality, Colin Kaepernick, “When civility leads to death, revolting is the only logical reaction. We have the right to fight back.”

The concentration of power and the possible bias is important because the social media have a strong influence on the U.S. and global public conversation. In the world population of 7.8 billion, the internet has 3.7 billion users. One in five Americans say that primarily they get their news from social media: about 48% of those aged 18-29 do so. The PEW research center survey of U.S. adults conducted in July 2020 indicates about two-thirds of Americans, particularly Republicans, believe that social media have a mostly negative effect on the country, because of their display of misinformation, hate, and harassment and their role in increasing partisanship.

The problem of the media is not new. It was John Adams who wrote in 1815 that a free press is necessary for the functioning of the Republic, but warned that it was also an invitation to abuse. President Abraham Lincoln in April 1861 accused newspapers in the border states of bias in favor of the South, and ordered many papers, supporters of slavery and sympathetic to the Confederacy to be closed.

Today, there are concerns about the degree of truthfulness, objectivity, and impartiality of the press, about the lack of clear distinction between news reports and opinion, about suppressing essential information or distortion of facts, and even Fake news. In general it is useful to outline what may be considered some of the categories of media bias; disproportionate coverage, reporting particular events over others and omitting others, misleading definitions, lack of transparency, the manner and tone of presentation of story, drawing inaccurate conclusions, or favoring a particular political party, advertisers, corporate owners of the media, stressing the exceptional rather than the ordinary, presenting a false balance despite evidence to the contrary, analysis or opinion rather than content, reducing events and ideas to a few passages that have a partisan point of view.

Evidence shows that the U.S. mainstream media have a leftist bias. Since 1989 a number of Americans stating there is a great deal of bias in U.S. news coverage has nearly doubled. The Gallup/Knight Foundation survey of September 2018 reported that 62% thought most of the news to see was inaccurate and biased, and that PBS News and Associated Press were least biased. Party affiliation is the key to how the media is viewed: 71% of Republicans had an unfavorable view of the news media, compared with 22% of Democrats. This difference was marked during the Trump administration. A study of the first 100 days of that administration showed that there was negative overall, 13-1, treatment by the press of his actions. There was not a single major topic where that treatment of Trump was more positive than negative. The closest result was on the issue of the economy where the record was 54% negative to 46% positive: on immigration it was negative 96-4%.

All studies, while they differ in degree, indicate that the majority of U.S. journalists identify as liberal/Democrats. It is, of course, arguable whether this results in bias in presentation of news. However, since ideological belief shapes what and how news is presented it is reasonable to conclude that it is not a myth that the mainstream media has a leftist/Democrat bias. It is not difficult to discern the difference. Two outlets are not leftist: Fox News Special Report, and the Washington Times, and a think tank, Heritage Foundation. Other outlet are liberal/leftist: CNN, the Washington Post, the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Time Magazine, Newsweek, the Detroit Free Press. The Wall Street Journal, which is bifurcated between its news section and its editorials, is generally seen as left of center.

The news bias towards the left is similar to that in other aspects of contemporary American culture: much of the academic world, the entertainment business, and late night TV hosts. It is wise that a democratic society has no one public truth, no orthodoxy, but it must have freedom of expression, except where there is clear and present danger. In its deliberations, the U.S. Senate must subject its beliefs to the test of unbiased information and conclusions.