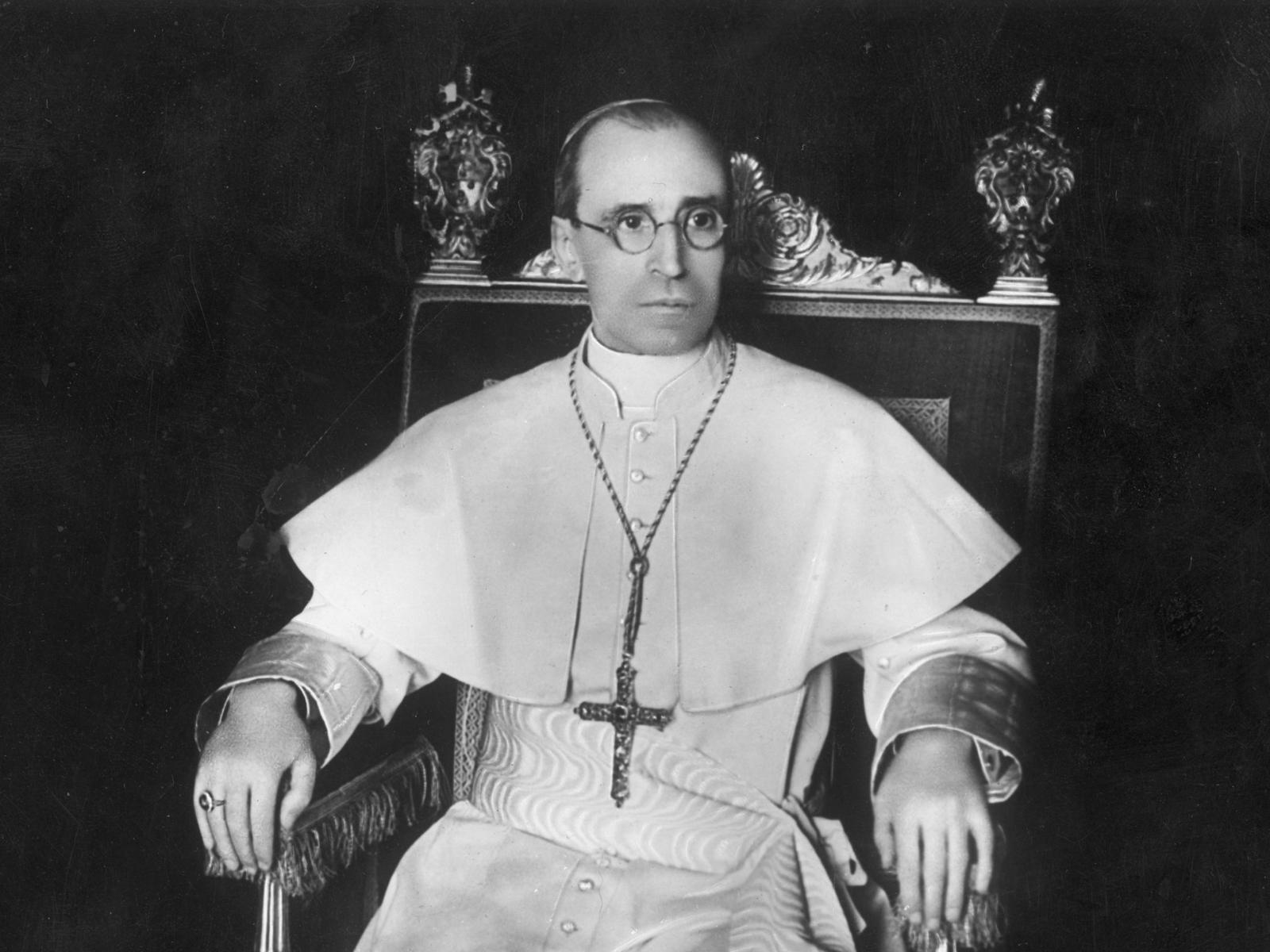

The Vatican and Pope Pius XII

by Michael Curtis

When the saints go marching in, I want to be of that number.

On July 4, 1941 Robert H. Jackson, then U.S. Attorney General, said that “whenever we reproach our own imperfections, we must not forget that our shortcomings are visible only when measured against the ideal, never against the practical living conditions of the rest of the world.” The historic dilemma is how to judge the behavior, the responses or lack of responses to evil manifestations, in enigmatic situations in which categorizing people as good or bad is not easy. This is particularly true of assessment of Pope Pius XII who has been the subject of public criticism for more than half a century.

After 30 years of pressure, the Vatican on March 2, 2020 opened the archives, amounting to millions of pages, on the Pontificate of Pope Pius XII, 1939-1958, which will be an important moment for commentaries on the recent history of the Catholic Church. The event coincides with the date of the election of Pius XII as Pope. The opening is opportune for two reasons: one is that it is appropriate after years of controversy over the actions during World War II of Pope Pius XII; the other is disagreement over the decision of former Pope Benedict XVI that Pius XII , and some others, were “venerable,” the starting point on the road to beatification and canonization as saints.

This second issue brings a problem for the Catholic Church of whether there are too many and too hasty proposals for canonizations. Historically, 19 year-old Joan of Arc, Maid of Orleans and heroine of France, was burnt at the stake in Rouen in 1431, and was only made a saint on May 16, 1920. The 40 Catholic English Martyrs of the 16th and 17th centuries, executed for treason during the Reformation, were not made saints until 1970.

Should Pius XII be canonized? Pope Benedict in 2009 said Pius had lived a life of heroic Christian virtue, which was a step to sainthood. However, Pope Francis in 2011 commented that no miracles had been identified, and that research and appropriate criticism would allow evaluation of Pius in the correct light. Evaluation of the archives to be opened will help settle the dispute as well as the broader issue of the character of the actions of Pius.

Pius XII is still the subject of heated debate as he has been for some time. If Pius XII was not Hitler’s Pope as John Cornwell asserted, he was not the first enemy of the Nazis as William Doino asserted. It is useful to survey briefly a few of the arguments on his activity as leader of the Catholic Church.

Among the many early strong attacks, some came from different countries. British author John Cornwell called Pius XII a “deeply flawed person, in his book Hitler’s Pope, published in 1999, the German protestant Rolf Hochhuth, in his 1963 play The Deputy asserted that the Pope failed to act or speak against the Holocaust, Americans Daniel Goldhagen, Garry Wills in his book Papal Sin, and James Carroll in Constantine’s Sword. The Greek-French film director Costa Gavras in film Amen in 2002 portrays a cowardly Pope indifferent to the fate of Jews being sent to Nazi camps where they were exterminated by poison gas, Zyklon B.

Cornwell’s controversial book probably had the most impact with his account of a Pope who failed to be gripped with moral outrage at the plight of the Jews. Essentially, Cornwell argues that the Pope had not done enough or spoken out enough against the Holocaust. He was, according to Cornwell, the ideal Pope for Hitler’s unspeakable plan and was Hitler’s pawn. The main interest of Pius XII was to increase and centralize the power of the papacy, and this was more central than opposition to the Nazis. He believed he was the ideal person to do this.

Interestingly, some years later, Cornwell qualified this bitter criticism by saying that Pius XII had so little scope of action that it was impossible to judge the motives for his silence during World War II, while Rome was under the heel of Mussolini and later occupied by Germany, Yet Cornwell, still talked of priests, including the Pope, once Cardinal Pacelli, as “fellow travelers,” who accepted the benefits that came with the Concordat with Nazi Germany, generosity for Catholic schools and teachers, in return for Catholic withdrawal from social and political criticism. The compromise, Cornwell saw, as collusion.

A more positive view came from a host of international scholars, Catholic, like the active historian William Doino, and non-Catholic. Among the latter are American rabbi David Dalin, and British historian Martin Gilbert. Doino, author of The Pius War: Responses to the Critics of Pius XII, held that Pius was not silent about the Holocaust. Dalin, in his book The Myth of Hitler’s Pope, published in 2005, argues that the Pope was responsible for saving hundreds of thousands of Jews during the Holocaust. Dalin condemned those critics who rewrote history and denied the testimony of Holocaust survivors. There should be recognition of his legacy, too little and unappreciated as a great friend of the Jewish people. The Pope was not silent, but publicly and privately warned of the danger of Nazism.

Martin Gilbert held, that far from deserving obloquy, Pius XII should be a candidate for “Righteous Gentile” in the Yad Vashem Museum in Jerusalem. Gilbert argues that the Pope’s Christmas Day message of 1942, condemning the extermination of people based on their race or descent, showed he was in fact condemning the Holocaust. Gilbert also asserted that Pius’s interventions and protestations helped save 4700 Jews in Rome, and that 477 Jews were given refuge in the Vatican.

Most recently, an Italian film Shades of Truth, directed by Liana Marabini, provides a positive image of Pius XII, attempting to rehabilitate his reputation based on documents covering the underground work of Pius XII to help Jews. The film includes the story of Israel Zolli, Chief Rabbi in Rome, 1940-45, who was sheltered and hidden in the Vatican, who converted to Catholicism after the war, and took the name Eugenio to honor Pius, originally Eugenio Pacelli. Zolli spoke of the holiness of Pius XII for his repeated and pressing appeals for justice on behalf of Jews, and his protests against evil actions and procedures.

The contrast between critics and defenders is stark. Was Pius XII Hitler’s Pope or was he the Catholic Church equivalent of Oscar Schindler, German industrialist who is credited with saving 1200 Jews? At the most extreme, was he an active collaborator with the Nazis or silent and acquiescent in their crimes? Was he most concerned with embodying the defense and preservation of the Catholic Church in Eastern Europe against the menace of Stalinism, and totalitarianism communism?

Pius XII had some strong views about the threat of communism, but less about Italian fascism and even German Nazism. The main complaint of critics is that the Pope remained silent or did very little, never emphatically condemned the Holocaust, believing that strong public criticism of Nazism would risk not only the Church as such, but the very lives of priests and nuns.

Pius XII (Eugenio Pacelli) was the Vatican’s chief diplomat, Vatican Secretary of State under his predecessor Pope Pius XI, and Papal Nuncio to Germany before becoming Pope in 1939.

As a diplomat he had to compromise with foreign regimes, sometimes evil ones. In 1933 he negotiated a Concordat between the Catholic Church and the Nazis, protecting the rights of Catholics. The Catholic Center party voted in favor of the Enabling Act, March 1933 which allowed Hitler to assume dictatorial powers. The party was dissolved by the Nazis three months later. The Pope refused to break diplomatic relations with the Nazis during the war, and did not condemn the Nazi invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939.

Did Pius XII do enough? The evidence is mixed. Pius XII never publicly criticized the Nazi regime directly. But he assisted his predecessor Pius XI in drafting, and probably wrote, the 1937 encyclical Mit brennender Sorge (with burning concern), written in German not Latin, which was critical of Nazi ideology. A major criticism is of Pius when 1016 Jews were rounded up by the Gestapo on October 16, 1943 in their ghetto in Rome near the Vatican. The Jews were deported to Auschwitz; only 16 survived. Pius made no public protest, though the razzia took place “under the Pope’ windows.” In 1943 he wrote to the Bishop of Berlin stating that the Church could not publicly condemn the Holocaust for fear of causing “greater evils.”

On the other hand, the Pius XII and the Catholic Church did protect Jews in Rome. He may be accused of passive acquiescence in Nazi crimes but he cannot be condemned for collaboration with the Nazis. The case for Pius is that he as head of a vast organization did what he could in the context of the times and the extent of his power. He appointed several Jewish scholars to positions in the Vatican after they were dismissed by their universities on racial grounds. He wrote two other encyclicals against totalitarianism. He sent letters to the Bishop of Naples to help with money to rescue Jews. He is said to have spoken sharply in March 1940 with Joachim von Ribbentrop, Nazi foreign minister, about breaches of the Concordat.

Evaluating the archives will take several years, but it is decisive for accurate judgment of Pius XII. Did the Vatican which was neutral during the war favor a pro German peace settlement? Most important for the intense historic debate is information on the validity of the disputed topics. The Vatican is said to have saved 800,000 Jews, and to have succeeded in removing 20,000 Jewish refugees from internment camps in northern Italy in September 1943. Jews were sheltered in ecclesiastical buildings on explicit instructions from Pius. Jews were saved by getting fake baptism certificates from the Vatican.

The opening of the Vatican archives will help ascertain history as it happened, not in terms of a partisan view of the past. The purest treasure is spotless reputation. It is intriguing to learn whether Pius XII can be characterized in his way.