“Treating” Evil

by Theodore Dalrymple

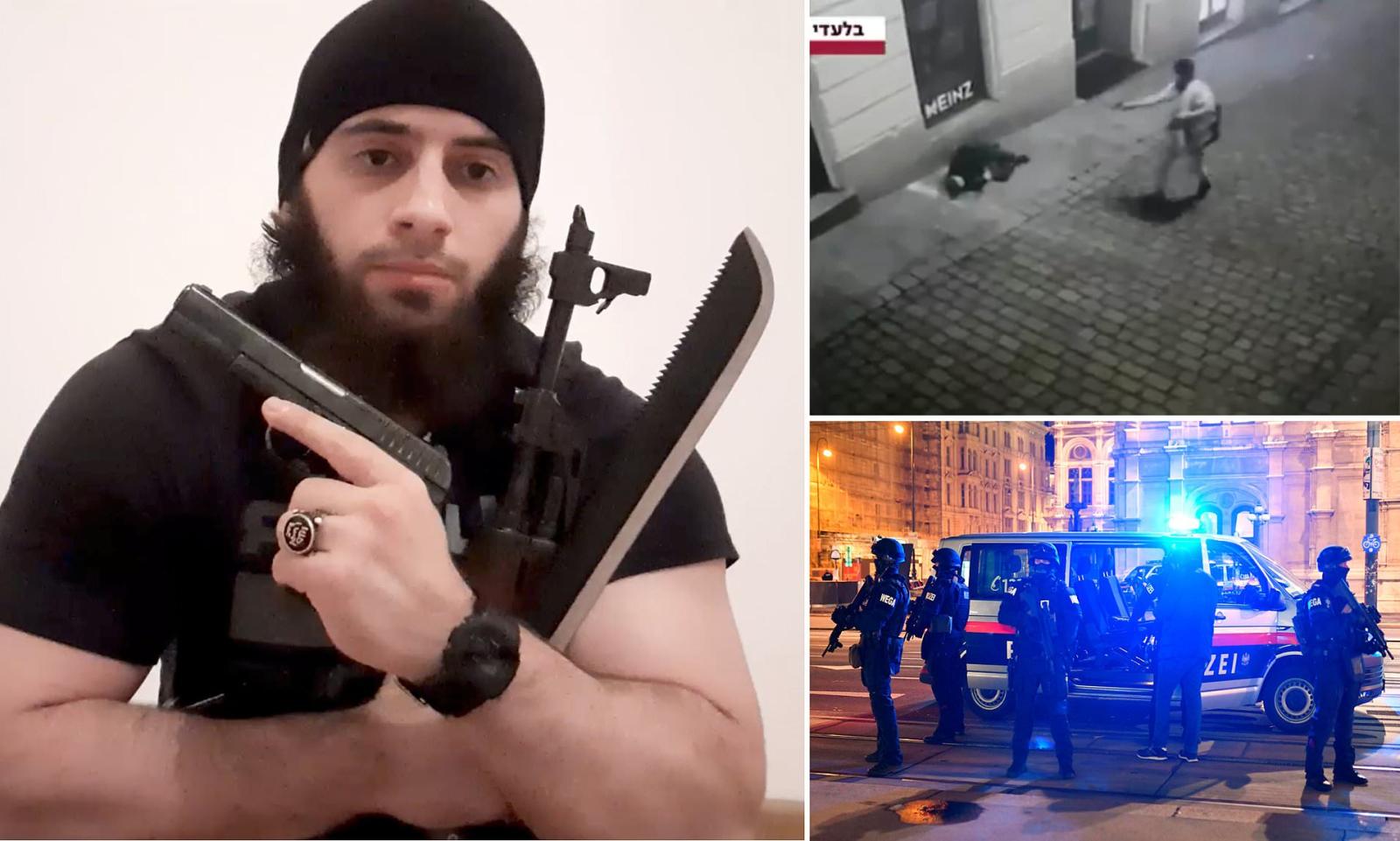

The ease with which Kujtim Fejzulai, the young North Macedonian terrorist responsible for the recent terrorist outrage in Vienna, was able to deceive psychologists, police, and other supposed experts into believing that he had abjured Moslem extremism, would have been funny, even hilarious, had its consequences not been so terribly tragic and deadly.

Fejzulai, a citizen of both Austria and North Macedonia, was released early from a prison sentence, imposed because he had tried to cross from Turkey into Syria in an attempt to fight for ISIS, with which he sympathised. He was released early from prison for two reasons: his youth (he was 20) and because he claimed to have seen the error of his extremist ways.

On statistical grounds, his youth might more sensibly have been a reason for detaining him in prison for longer, even for much longer, because it is precisely during their youth that young men such as he, who are attracted to violence, are most likely to commit it. A sentimental view of youth, however, prevailed over a more realistic one.

But the second reason for his release was even more absurd, and revealed the arrogant technocratic mindset of so many western authorities and governments, which suppose not only that there is a technical solution to all human problems, but that they have found it. They imagine that, since they are representatives of the richest and most advanced societies in the world, they must have techniques to change the “primitive” mindsets of Moslem extremists. Surely it is not possible for people with a world outlook that belongs more to the seventh than to the twenty-first century, to fool people with doctorates from reputable and even venerable universities, who have access to the latest technology and all the information in the world?

The fact is, however, that any ignorant and stupid seventh century-minded extremist is more than a match for any number of psychologists, criminologists, sociologists, computer scientists, etc. While I cannot sympathize with his outlook to the slightest extent, in a sneaking or convoluted way, I am glad that he is up to the task. His ability so easily to deceive means that technocracy is still not triumphantly successful—as I hope that it never will be. Our humanity is preserved by the fact that so-called deradicalization is a charade. What Fejzulai needed was not a technical procedure, with a technical assessment as to whether or not it had worked, but thirty years or more in prison to cool his heels: for society’s sake, of course, rather for than his, though it is probable also that it would have saved his life.

The technocratic approach according to which Moslem extremism is a quasi-medical or physiological problem, to be “treated” as if it were an illness, is applied not only in cases of terrorism but in that of crime in general. This is a corollary of the belief that crime is not a choice of the criminal, albeit a bad one, but a problem of physiological development, such that punishment is a kind of moral orthodontics.

Parole is granted to, or withheld from, prisoners based on speculations as to whether or not they are truly reformed. But in fact there is no means by which the truth of such speculations can proved beyond reasonable doubt.

This is far from a new theory. I happened recently to pick up a volume of the Quarterly Review for December 1847, in which there was an anonymous article about the treatment of prisoners. There were two theories of imprisonment as a punishment, the article said, the first being the protection of society by deterrence, both of the offender and others who might otherwise be tempted to behave like him.

The second theory was that of the moral reformation of the prisoner. This theory was succinctly expounded by a judge in Birmingham, who was in favour of it:

By a reformatory system we understand one in which all the pain endured strictly arises from the means necessary to effect a moral cure. A prison becomes a hospital for moral diseases.

Both theories, of course, are compatible with the most revolting cruelty: for such cruelty could conceivably lead both to deterrence and moral reform.

In other words, efficacy is not by itself a complete justification for any kind of punishment: civilised conduct imposes its limits. But the second of the theories has an additional disadvantage, namely that it often leads to injustice and is incompatible with the rule of law.

Parole is granted to, or withheld from, prisoners based on speculations as to whether or not they are truly reformed. But in fact there is no means by which the truth of such speculations can proved beyond reasonable doubt. The case of Kujtim Fejzulai shows just how easily those who devote their whole professional lives to the “assessment” of such people may be deceived. One might have thought, a priori, that it was obvious that feigning repudiation of terroristic ideas was not very difficult; indeed, only someone with an exaggerated and even arrogant belief in his own powers to penetrate the minds of others would suppose otherwise.

Naturally, there is an opposite risk, namely that of assessing someone as dangerous, and of therefore refusing him parole, who in fact is not dangerous. Probably this error is at least as prevalent, and leads de facto to more severe punishment than of someone who, on equally flimsy grounds, is released on parole: though it does not have the catastrophic effects on society that errors of the first type have.

But the early release of such as Kujtim Fejzulai has another deleterious effect, whose size or importance is impossible to estimate with certainty: namely, that it is yet further proof, at least to those already thinking along these lines, of decadence and weakness in the West, which is a rotten fruit whose tree only needs a bit of a shake for the fruit to fall. If a society is so sentimental about its enemies as it was in the case of Kujtim Fejzulai, what powers of resistance against determined attack could it have?

In other words, the very idea of deradicalization is an encouragement of Islamic terrorism, and the technocrat in general, and the psychologist in particular, is the unwitting ally of the machete- and Kalashnikov-wielding fraternity of fanatics. In what contempt must they hold those who claim to be able to reform them: a contempt that in a certain sense is justified.

First published in the Library of Law and Liberty.