by Michael Curtis

The Duke of Mantua, singing what has become the showcase aria for tenors, deliberately or genuinely misled by his la Donna e Mobile (woman is fickle) and that women were qual piuma al vento (like a feather in the wind). The aria exemplifies the reality that patriarchy, including the influence of husbands and the social world in general, has dominated the classical musical world as in other area of life. Even if one believes that in the past or in the present there are no women composers as great as male counterparts, the compositions of women in the classical music field which have been considerable, have been stifled or neglected, or assumed to be inferior to those of men.

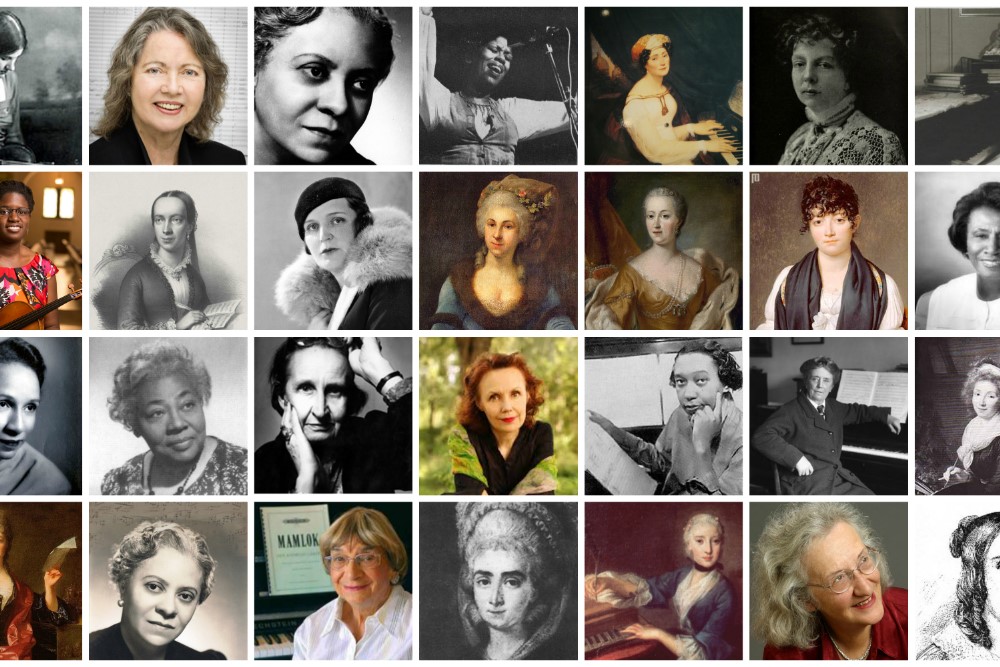

Throughout history there have been centuries of music composed by women, much of it lost or neglected. The list of women is long, going back to Hildegard von Bingen, 12thcentury Benedictine Abbess, who wrote 77 sacred songs and a drama set to music; Barbara Strozzi , 1619-1677, prolific composer of secular vocal music; Francesca Caccini, 1587-1641, whose surviving stage work is considered to be the oldest opera by a woman composer; Louise Farrence, 1804-1875, brilliant pianist and composer who demanded and received the same equal pay as men composers; Camilla de Rossi 1670-1710, Roman Italian who wrote for the north Italy and Vienna areas and had a keen interest in tone color; Marianne Martinez, 1744-1812, Austrian, who began composing at age 16, and is said to be the only author of a symphony composed by a woman during the late 18thclassical period,; Fanny Mendelssohn, 1805-1847, composer of 460 works, some of which were published in the name of her more famous brother Felix; Clara Wieck Schumann 1819-1896, wife of Robert, not only a great pianist, but a composer who completed her piano concerto at age 14, composed 66 works, but stopped composing at age 36, partly because of her view that “a woman must not desire to compose,” but mainly because of her active performing career and caring of her eight children, and fulfilling the demands of the ailing Robert.

Among the women composers in the last two centuries are Amy Beach, 1867-1944, the first successful U.S. composer, mostly of romantic music whose Gaelic Symphony was played in 1896 by the Boston Orchestra; Germaine Tailleferre,1892-1953, the only women in the Montparnasse group Les Sixthat included Francis Poulanc, Darius Milhaud, Arthur Honneger, Georges Auric, and Louis Durey, and which among other things influenced Virgil Thomson; Lili Boulanger, 1893-1918, who won at age 19 the Prix de Rome, the first woman to do so, for composition, and who died young aged 24; Ethel Smyth, 1858-1944 whose “March of the Women” became the anthem of the suffragettes movement; Elizabeth Maconchy who at age 23 had a work performed at the BBC Proms, and in 1952 won the competition to compose the Coronation Overture, Proud Thames, for the crowning of Elizabeth II; and in the sphere of jazz Mary Lou Williams, 1910-1981 with hundreds of compositions including “In the Land of Oo-Bla-Dee” for Dizzy Gillespie.

Yet there has always been, in the classical music sphere as elsewhere in life, a lack of gender equity. Unquestionably, the percentage of women playing in major symphony orchestras in the world has increased, though disparity remains, and women still constitute less than half of major orchestra musicians. Women in the present as in the past, have always had a place at piano, in church and elsewhere. Psychologists have viewed this as women maintaining an upright, modest position. Men in orchestras are more likely to be players of the double bass, percussion, trumpets and trombones, while females dominate in the flute, and often in the violin section. Moreover, disparity is illustrated by studies showing that in a blind test, women are more likely, by as much as 50%, to be chosen than in the case of a non-blind test.

In choices of instrumentalists and conductors, considerations of appearance and dress of women have been more relevant than in the case of men. Conducting is still a glass ceiling, and some prejudice and misunderstanding is evident about what is appropriate standards and behavior for women conductors. People may perceive and interpret gestures, especially those of command, on the podium differently in the case of men and women. Some critics have unkindly remarked that when women are conducting, audiences and musicians may begin thinking about other things than music.

The figures are clear though they may differ in detail. Some analyzes estimate that only five of the world’s 150 top conductors were women: in the 103 highest budget U.S. orchestras, male conductors accounted for 91, while female were only 12. Of the conductors of the 12 largest budget U.S. orchestras, 21 were men and 1 was female. However, the number of women conductors is increasing. Among the more well known are Marin Alsop, Bournemouth (UK) and Baltimore, and Last Night of the BBC Proms in London, Gisele Ben-Dor, Uruguayan-Israeli, Santa Barbara, Odaline de la Martinez, Cuban born, first to conduct at BBC Proms, Sarah Caldwell, first woman to conduct at Met Opera, NYC, Sian Edwards, English National Opera, Jo Ann Falletta, Virginia and Buffalo, Australian Simone Young at Vienna State Opera, and Vienna Philharmonic.

Evidence suggests an automatic bias by music audiences that a concert including compositions by women would be a reduction in quality. The disparity continues. Compositions by women account for less than 2% of all classical music performed. A survey of works performed in 2018 in 1,445 classical music concerts around the world, indicates that only 76 works were composed by women. The Donne-Women in Music Project reported that of the 3,524 works performed at these concerts, 3,442 (97.6%) were by men, and only 2.3% were by women. Other surveys make the same point. One indicates that in 2016-7 of the 21 leading orchestras, including LA, San Francisco, Cleveland, 14 did not perform a single work by a woman composer, and three others, Houston, Milwaukee, Seattle, performed only one.

To overcome the gender gap, the Women’s Philharmonic, 1980-2004, was founded in San Francisco to compensate for the underrepresentation of women in the mainstream classical music world by creating an orchestra composed entirely of women, performing music composed by women. It was not the first in history, but was unique in the U.S. In its years it presented works by more than 160 women composers. The National Women Conductors initiative was launched in 1998 to promote women conductors; part of its function taken over by the American Symphony Orchestra League.

The Women’s Philharmonic Advocacy, a non-profit organization was founded in 2008 to recognize the achievements of the WP over its 24 years. Its objective is to advocate the performance of works by women composers and to address the place of women in today’s repertoire.

No doubt changes are occurring. The WP did promote women performers, conductors, and composers. The British Royal Opera has announced two courses for new women conductors for opera and ballet to start in 2019. The percentage of women in major symphony orchestras has increased as has the number of women conductors.

But the gap remains as far as women as leaders and composers are concerned. Surveys indicate there are no women concert masters in major U.S. orchestras, nor are more than a few, if any, music directors in the large orchestras of the world. No woman is yet in the canon of classical music composers. It is time for more emphasis on the music composed by women than on their private lives.

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

2 Responses

Good article but no photo of Deirdre Hickey?

Are you really advocating for some kind of orchestral affirmative action? Why can’t we just admit that there are substantially more male conductors for the simple fact that men are better natural leaders? Why should this disparity be socially engineered away just because of some egletarian ideology? All that should matter is the quality of the music and its performance.