Christopher Columbus Deserves to be Defended

by Armando Simón (October 2019)

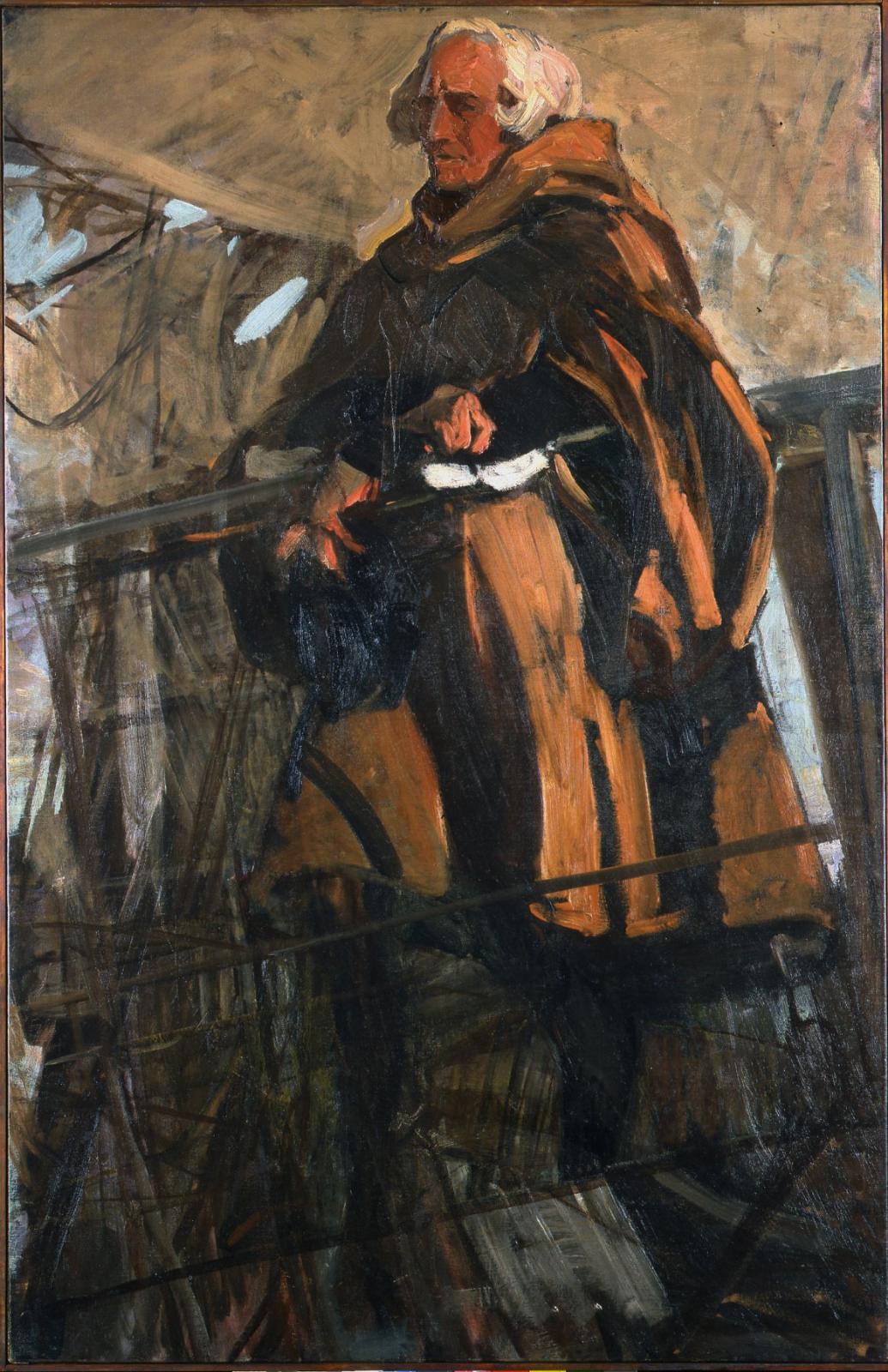

Columbus Leaving Palos, Joaquin Sorolla Y Bastida, 1910

As we once again approach the anniversary of Columbus’ discovery of the New World, leftists will once again posture in self-righteous snarls and re-hurl all sorts of accusations at the explorer. Some of them will be snarky comments, like saying he was not the first one to discover the new continent, the Vikings, or the natives were—which means absolutely nothing since the rest of the world remained ignorant of its existence, or by pointing out that he was wrong in believing that he had reached Asia, which proves he was incompetent (again, an asinine declaration). In his own time, some Spaniards also belittled his achievement, which resulted in the famous story of the egg.

Another snarky comment is that Columbus was interested in finding gold.

So what? He was poor. Spain was poor. Europe was poor. Even today, persons who are truly poor (not “American poor,” which means simply not owning a car, but dirt poor as in Third World countries) are constantly preoccupied with money. Just like well-off people in First World countries.

Read more in New English Review:

• Journey Down the Rift

• The Danish-Swedish Rivalry and the Scanian Regionalism

• Christopher Columbus Deserves to be Defended

Some of the more extreme accusations against Columbus was that he was “a war criminal,” which, if nothing else, demonstrates leftists’ propensity for mutilating the language. And history. Through perseverance, these accusations have saturated the culture and can be found in the most unexpected of places. In one of the episodes of the TV show, The Office, one of the characters casually mentions that Columbus carried out genocide. In another show, The Good Place, it is casually mentioned that he is in hell because of rape, war, and genocide (“genocide” is one of the left’s favorite buzzwords). And the ignorance is breathtaking. The Daily News writes,

First President Trump hailed the carved symbols of Confederate racism as ‘beautiful,’ and now he’s defending statues dedicated to Christopher Columbus—the man responsible for genocide of North America’s indigenous people.

Columbus never even set foot on North America!

It is telling that the people who become immediately indignant at Columbus’ supposed crimes and “genocide” and “war crimes” lose all indignation if the crimes and the genocides of the Communists are brought up. In fact, they become indignant if they are brought up.

Now, there is no question whatsoever that the discovery was a catastrophe to the Stone Age cultures that existed. Bartolomé de las Casas, the famous Apostle of the Indians, extensively wrote and detailed the sickening crimes that the Spaniards carried out on the natives, which rivaled the sadism of the Mongols, the Muslims, and the Khmer Rouge. All the Indians that lived in the Caribbean islands were wiped out. And the same result would have happened if the Asians or Africans had conquered the New World instead of Europeans. However, the (deliberate) falsehood that has been bandied about is that Columbus himself carried out those atrocities. To my knowledge, de las Casas never mentioned Columbus as having done so in the Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias, and de las Casas never held anything back. Even if it is acknowledged, to say that he is responsible for the Conquistadores’ later acts simply for discovering the New World is like saying that Nobel is responsible for the deaths caused by later explosions. This kind of logic reminds me of those individuals who blame Charles Darwin for the antics of new-Darwinists.

In reading over several of the primary sources of his exploration, again and again I come across entries wherein Columbus insists of treating the natives that he encounters in a friendly and kindly manner and simply trade with them and gain knowledge of the land; he has to continually hold back the men under his supervision that just want to rape and steal from the Indians, including jumping ship for just that purpose. Later, many of the Indians hate and despise the Spaniards but continue to have honest dealings with him. Incidentally, because of his detailed narrations of the natives’ religion, beliefs, ceremonies, etc., Edward Bourne considered Christopher Columbus to have been the first anthropologist of American native cultures.

Read more in New English Review:

• The Jews Should Keep Quiet

• Our Power-Hungry Pharisees

• 911, Isis, Iran, & Al Qaeda: Defeating Contemporary Amalekites

David Wootton’s massive The Invention of Science gives us a fresh perspective on the significance of Columbus’ voyages of exploration, which is also well worth contemplating on this anniversary of the landing in the New World.

Regardless of one’s views on the man, his discoveries were earthshaking. The voyages caused a chain reaction.

First and foremost, his voyages of exploration created an upheaval in European intellectual thought. Up to that point (and for some time afterwards in rigid minds), it was the set in stone, very rigid, belief that the ancient Greeks had discovered everything that there was to know, particularly by Aristotle, who had compiled what we would roughly call an encyclopedia. Scholars during the Renaissance searched for ancient manuscripts in monasteries, hoping that they would yield more knowledge while the rest, and most, of the remaining scholars (in universities) would debate the finer points of Ptolemy, Aristotle, etc.

It came as a thunderbolt to suddenly realize that there was another, entire antipodal, continent aside from Asia, Europe and Africa. Simultaneously, there came a flood of knowledge of new peoples, animals, food, vegetation, languages, unknown to the Ancients. Furthermore, the discovery had been made not by any outstanding scholar, but by a common sailor, with the obvious implication that anyone could just make similar discoveries. And become famous. It also threw a monkey wrench in the Ptolemaic system of the universe which would ultimately collapse with the advent of the Copernican view. Such was the ossified European mindset up to then, that with Columbus’ voyages, it became suddenly apparent to one and all that knowledge and, therefore, progress was cumulative, rather than static and complete. Something that Wootton does not point out that supports this rigidity of worldview is the fact that Columbus to the end continued to think that he had, indeed, reached Asia, though not the country of Cathay.

On top of that, he points out that new words had to be invented to describe what was going on (after all, one word can encapsulate a paragraph of explanation). And so, it was the Portuguese who first invented the word “discovery.” Other words that were slowly invented were “science,” “experiment,” “exploration,” “facts,” “scientist.” Incidentally, no one had really believed that the world was flat. Instead, there were spheres within spheres. The flat earth idea came into being as a sort of urban legend in the 1800s to describe the previous world view.

Within a century of Columbus’ voyages, science took off, aided by the inventions of the telescope, the microscope, the printing press, the barometer and thermometer and it is in this period that Torricelli, Galileo, Kepler, Tycho, van Leeuwenhoek, and William Harvey appear. The printing press, in particular, with the subsequent massive proliferation of books and book fairs, suddenly united isolated scientists. Books also facilitated accuracy through engraving of machinery and organisms (instead of flawed copying of texts, as had been the practice). A paradoxical culture of cooperation and competition among scientists was created that persists to this day. Galileo, for instance, printed his findings and, within two years, anyone could verify that Venus had phases, that the moon had mountains, and that Jupiter had moons, telescopes having become commonplace (however, some scholars famously refused to look through the telescope because Aristotle and Ptolemy had decreed that the planets had no moons). “Replication” of experiments became common.

Likewise, anyone could get on a boat and verify Columbus’s discoveries. Anyone could become famous. Anyone could make discoveries. And you did not have to know Greek.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

__________________________________

Armando Simón is a Cuban native and the author of Very Peculiar Stories, A Prison Mosaic, Samizdat 2020, and The Cult of Suicide and Other Sci Fi Stories.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast