The Challenge of Chance

by Theodore Dalrymple (June 2018)

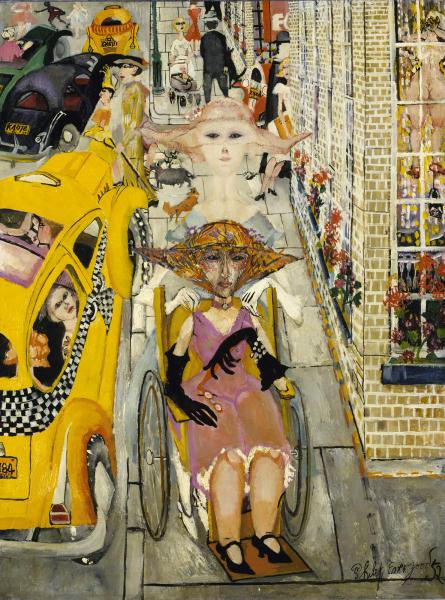

Dowager in a Wheelchair, Philip Evergood, 1952

Chance plays a larger part in our destiny than we would like to suppose, though that does not make us any the less responsible for our actions. After all, every decision has to be taken in circumstances, often not of our choosing: and is a life even conceivable in which men act only in circumstances that have been chosen and brought about entirely by themselves? It is our existential burden (or is it glory?) always to have to act as best we can.

I happened the other day to be passing a charity shop outside which a box of books at derisory prices had been placed. Among them was a copy of Philip Roth’s novel, Nemesis, and I started to read. Quite apart from the subject matter—a polio epidemic in Newark in 1944—the price, about 70 cents, encouraged me to buy it. The decision was mine, of course, but chance played a large part in it.

The plot of the book is simple. The protagonist is (at first) a healthy, optimistic, unreflective but excellent and dutiful though not brilliant young man who is rejected by the armed forces in time of war because of his severe short-sightedness. Athletically inclined, he is a teacher of physical education who is in charge of a playground when the polio season begins. There are more and more cases, some of them fatal, and eventually his girlfriend, soon to be his fiancée, persuades him to leave Newark and take a job at a summer camp for children and adolescents in the nearest mountains where he should be safe. Alas, he brings polio with him, and soon an epidemic starts in the camp. He himself comes down with the disease, and suffers permanently paralysed limbs. He breaks off his engagement with his fiancée, with whom he has been so happy, even though she does not want him to, because he feels that not to do so would be to trap her into a life of looking after a cripple. This for him would be yet another betrayal committed by him: the first having been to betray his country militarily by his unfitness for service, the second having been to desert his Newark playground in the throes of an epidemic (though he could have done nothing to halt it), and the third having been the introduction of the polio virus to the holiday camp.

Towards the end of the book we learn that the narrator, who has until then remained firmly in the background, was himself one of the children in the protagonist’s playground, a few years younger than he; and that he too contracted polio in that polio “season.” He writes from the viewpoint of the 1970s, when he runs into the protagonist again. The contrast between them is great. While the narrator has married, had children, and pursued a career, that is to say made the most of things, the protagonist in effect retired from life. He obtained nondescript and dull office employment, never married or had any further romantic attachment, always leading a very restricted social life. It was almost as if he had decided that he was unworthy of life and was merely waiting for death, which alone could assuage his guilt. He blamed himself for what he was causally, though not morally, responsible. He allowed mere chance and ignorance with regard to the transmission and prevention of polio (not his own ignorance alone, but that of everyone of his time) to blight his life.

The story was particularly powerful for me because when I was about five, perhaps six, my closest friend, who lived a few doors away and from whom I was then inseparable, contracted polio. It was in the year before, or perhaps in the very year, a vaccine became available (I remember lining up and taking it on the sugar lump), and more or less eradicated the disease at a stroke. My friend would have been one of the last cases; if anyone had reason for bitterness it was he.

My parents must have been very anxious on my behalf, though they never subsequently spoke of it. I, of course, gave their anxiety no thought; children do not generally consider their parents’ worries on their behalf because they assume that nothing can be otherwise than it is. On the contrary, they take the world as given and later, when they realise that it is not, they are preoccupied with other things than their parents’ former anxieties. In fact, it was only after my parents’ death that I appreciated how worried they must have been and how well they behaved towards my friend after he was stricken with paralysis. They included him as far as possible in our daily life without making any fuss, and certainly without those unctuous expressions of sympathy or compassion that might have encouraged in him a state of self-pity (however understandable that might have been). Therefore, my parents played a small and honourable part in my friend’s subsequent great success in life and career though, perhaps paradoxically, it was his mother’s belief in Christian Science, which holds that illness is error and illusion cause by lack of faith, that really preserved him from the tempting refusal to participate to the full in life—much more fully, in fact, than most people.

Looking back on it, I am still haunted by the question of why him and not me. The question must have an answer of a commonplace kind, of course: that we were differentially exposed to the virus, for example, or differently susceptible to its effect for some physiological or immunological reason that in theory would be discoverable by empirical science. The answer will never be found because no one will ever look for it and it is far too late to do so: but there would be no inherent mystery in such an answer.

And yet, even if such an answer became available to me, I do not think that my initial question would have been answered entirely to my satisfaction. There are philosophers, no doubt, who would claim that the question could have no other kind of answer than this: and that if, for example, it were found that we had different blood groups and different blood groups were differentially susceptible to polio, there would remain nothing further to be said. If I were then to ask why we were of different blood groups, the answer would make reference to the DNA of our parents, etc. There might be an infinite regress, indeed, of such questions, there being no ultimate explanation, no end point, each answer giving rise to yet another question. And since in practice our enquiries have to end somewhere, and our curiosity is limited, we might as well for most purposes stop at the first answer.

But my initial question, why him and not me, calls for an answer deeper (or so it seems) than merely that his viral load was greater than mine. I want an answer of a different kind, even if I accept that there cannot be one. I want an answer that implies a purpose to the difference, though what it could be I can’t really imagine. But if there is no such purpose, then life becomes, to an unacceptable degree, just one damned thing after another: for, as I have already said at the outset, chance plays a larger part in our destiny than we would like to suppose.

In my childhood friend’s case (I have long since lost touch with him, meeting him again briefly after more than forty years’ separation, a proportion of our life too great simply to resume where we had left off), I cannot imagine that his illness was sent merely to test him—though it did test him, and was a test that he passed with flying colours. What possible purpose could there be in inflicting such an illness on one five or six year-old child and not on another, no worthier or unworthier than he? Perhaps a world in which such seemingly arbitrary things happen is better than a world in which they do not, but I would not like to try that argument out on someone who has suffered from or is suffering from some dreadful disease that makes life a torment.

I look back on my life and think that I have been very fortunate, even to the extent that I have been able to determine my own fortune. There have been many people more fortunate, no doubt: handsomer, cleverer, more gifted: but in the existential raffle, I did not do too badly, winning perhaps the 1,278,563rd prize. In the context of billions of lives, that is not too bad

Philip Roth’s protagonist is very anti-God, not in the sense that he is a simple atheist, but in the sense that he both disbelieves in His existence and hates Him for doing all that he did to him. Someone (I suppose I could look it up on the internet) once said that no man is an atheist in the dark, to which one might add that no man is an atheist in undeserved misfortune. A man who doesn’t believe there are fairies living at the bottom of his garden doesn’t waste his time or mental energy denouncing their defective moral qualities or the damage that they do.

In other words, it is harder to disabuse ourselves of the notion of an overall purpose or intention to existence than we like—or some of us like—to imagine. Perhaps that is because we are such purposive beings that we find it difficult or impossible to conceive of events without purpose. I have noticed that in many books by overall-purpose denying evolutionists, who almost militantly argue against any teleological view of anything, that they are rarely if ever able to expunge from their language locutions of purpose or ultimate ends. “Evolution does this,” they say, or “evolution has so arranged it . . .” etc. It is as if they conceived of evolution as a demiurge carrying out a prearranged plan.

None of this means that there actually is such a plan, that everything is working towards a grand denouement other than empirical evidence (were there anyone around to observe it) of the truth of the second law of thermodynamics. I point merely to the psychological difficulty we have in eliminating purpose from our thoughts about existence as a whole. By the same token, I have difficulty in imagining what such a purpose could possibly be, even—or especially—for a Supreme Being. This may, of course, point only to a deficiency in my powers of comprehension; there are, after all, many things that I don’t understand, even at a perfectly mundane level, for example why intelligent people should want a tattoo.

There are philosophers, particularly recent philosophers, who argue that it is up to us to seek purposes for ourselves and not to seek to fit in with what we believe, on inadequate evidence they say, to be a transcendent purpose. On this view, one goal in life must be as good as another, since there is nothing external to the goals themselves by which to place them in some kind of hierarchy or worthiness or importance. All I can say is that, while many philosophers may say that they believe this, I doubt that many of them have been completely indifferent in practice as to what their own children chose as their goals in life: in other words, that they, the philosophers, acted as if they believed there was a better and worse, a higher and lower, and not merely because they think that one goal leads to earthly happiness while another does not. There are many things that might conduce to the happiness of an evil person, but the philosophers would not therefore condone or encourage the pursuit of them by their children.

Philip Roth is a self-proclaimed atheist who has said that he thought human life will be happy when people—all people—stop believing in God. His short novel is nevertheless very nearly a meditation on theodicy.

_____________________________

Theodore Dalrymple’s latest book is Grief and Other Stories from New English Review Press.

More by Theodore Dalrymple.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast