The Controversy over the Ken Burns Film, FDR and the Holocaust

A Discussion with Rafael Medoff

by Jerry Gordon (October 2022)

PBS Stations recently have held special premieres across the US country to showcase the long-awaited new Ken Burns (along with Lynn Novick and Sarah Botstein) documentary film, The US and the Holocaust. The shows have shown featured excerpts of the film before live audiences, followed by panel discussions at local affiliates, some with children of Holocaust survivors discussing their family horrific experiences and traumas.

After the three two-hour episodes of the Ken Burns film aired nationally on September 18, 19 and 20th, the videos became available on Amazon Prime. It has mainly been reviewed favorably by the mainstream press.

Burns use the film to conflate a personal view that he sees his documentary as a way to advance a political agenda to deal with the rise of contemporary issues such as immigration, racism, antisemitism and authoritarian regimes imperiling democracies. This is reflected in what he sees as an imminent threat of authoritarianism. That is reflected in his Guardian interview remarks:

The story of the Holocaust reminds us of the fragility of democracies but how, as frustrating as they can be, there is nothing more important than maintaining those democracies.

We were obligated to do that because the way we mount this series is we begin with antisemitism in America and racism and the pernicious slave trade, xenophobia, nativism, and eugenics. We’re obligated then to not close our eyes and pretend this is some comfortable thing in the past that doesn’t rhyme with the present.

Some of his statements have provoked criticism that he is comparing conditions in America today to the Nazi period. Another major theme of the series is to minimize President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s responsibility for American policy toward Jewish refugees during the Holocaust. Burns claims FDR’s hands were tied by public opinion. Many historians see it differently.

Note this Burns comment from the Guardian interview:

Six million Jews were killed. America, proudly a nation of immigrants, symbolized by the Statue of Liberty and welcome mat for “huddled masses,” fell short of its ideals.

That’s not entirely on Franklin Roosevelt, that’s on the Congress and the people of the United States who consistently voted against it, even when the horrors were revealed.

However, in the wake of its launch the Burns film has become controversial because the underlying theme suggests that President Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR), the Commander in Chief and leader of the allied victory in World War Two was somehow unable to rescue many of the Six million European Jewish Men, Women and Children from the Nazi Final Solution.

Why? Because of nativism, racism, rampant isolationism in the face of the Nazi conquest of Europe, anti-Semitism, the Economic Depression, and draconian immigration laws.

But FDR didn’t want to hear about the plight of mass murder of Jews by the Nazis. In July 1943 he was visited in the Oval by Jan Karski heroic Polish diplomat and courier who told him of atrocities he witnessed after being secreted into the Warsaw Ghetto and transit camp for the Belzec death camp. Instead, Roosevelt talked off carving off East Prussia for a post War Poland and whether the Nazis got their horses from Poland.

FDR is portrayed as almost the ‘victim’ of his own State Department visa and the immigration quota system implemented by his close friend and political ally, run by an anti-Semite, Assistant Secretary Breckenridge Long. Long, an acquaintance of the President’s WWI circle of Wilson Administration officials was appointed as Assistant Secretary of State after first serving as US Ambassador to Mussolini’s fascist regime from 1933 to 1936. Long had outraged many with his sympathetic remarks about Italian fascism. Long was promoted by Roosevelt to oversee 23 of the State Department’s 42 divisions. What the Burns film does not explain is that Long regularly briefed the president on the tactics he was using to suppress Jewish immigration. It’s not as if Long was some rogue actor; he served FDR.

Long’s denial of more than 190,000 visas for rescue of German and other Jews facing death, suppression of reports of systematic mass murder of Jews under Nazi occupation and lies before Congress about 580,000 Jewish refugees being given sanctuary got him sacked.

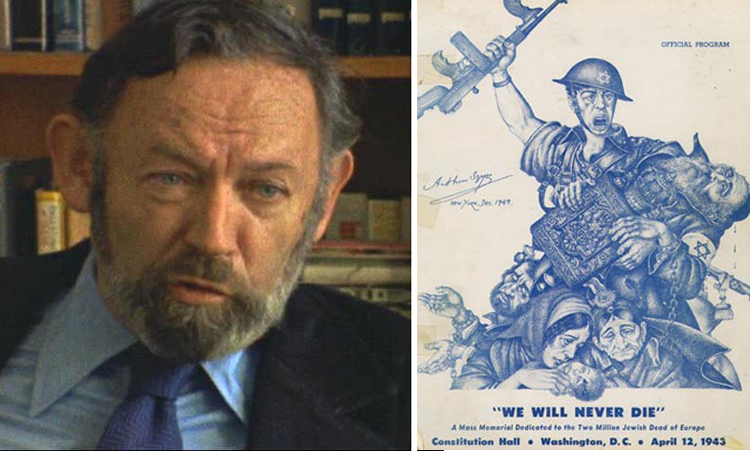

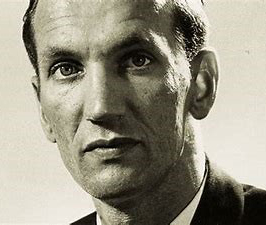

For his views on the Burns film and the historical issues it addresses, we reached out to Dr. Rafael Medoff, founding director of The David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies and author of more than 20 books about the Holocaust and Jewish history. One of those books, titled, Too Little, and Almost Too Late: The War Refugee Board and America’s Response to the Holocaust. , was the first book ever published about the War Refugee Board (WRB), one of the topics addressed in the Burns film. Dr. Medoff has also researched and written extensively about other major controversies of the period, such as activities of the activists known as the Bergson Group, and the Roosevelt administration’s refusal to bomb the railways to Auschwitz.

For his views on the Burns film and the historical issues it addresses, we reached out to Dr. Rafael Medoff, founding director of The David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies and author of more than 20 books about the Holocaust and Jewish history. One of those books, titled, Too Little, and Almost Too Late: The War Refugee Board and America’s Response to the Holocaust. , was the first book ever published about the War Refugee Board (WRB), one of the topics addressed in the Burns film. Dr. Medoff has also researched and written extensively about other major controversies of the period, such as activities of the activists known as the Bergson Group, and the Roosevelt administration’s refusal to bomb the railways to Auschwitz.

Long committed this calumny during testimony before Congress in 1944 seeking at FDR’s request to kill a Resolution calling for an agency to rescue Jews by falsely showing that it was unnecessary. When found out by an enraged Washington, DC press and Members of Congress, FDR was caught in a political embarrassment. After being confronted with information prepared by the staff of his Dutchess County neighbor, Treasury Secretary, Henry Morgenthau, Jr. he was forced to abandon his opposition and signed an executive order implementing what became the War Refugee Board that became populated by the Treasury staff whistleblowers led by John Pehle. The WRB, while a public agency was financed by 90 percent from private Jewish agencies like the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee and the World Jewish Congress.

The Resolution was the brainchild created by a group of Palestinian Jewish Zionists called The Bergson Group named after the nom de guerre of its founder, Peter Bergson (Hillel Kook). The Bergson Group came to this country in 1940 to recruit a Jewish Army to fight the Nazis. After learning of the mass murders of millions of European Jews they decided to try and save the remnant. They created conscious-raising musical stage pageants We Will Never Die with text by Ben Hecht, music by German Jewish refugee Kurt Weil with a casts of hundreds including Hollywood actors like Edward G. Robinson and Paul Muni. The pageants were performed in major American cities including Washington, DC where Eleanor Roosevelt and Members of Congress attended. That and full-page ads in major newspapers enabled The Bergson Group to lobby in Washington, DC for a government agency to rescue Jews. Just before Yom Kippur in 1943 the Bergson Group brought 400 Orthodox rabbis to Washington, who met with supporting members of Congress and proceeded to march to the White House, where they wanted to present a petition to FDR to form such an agency. FDR instead, on advice of his principal Jewish advisor and speechwriter Samuel Rosenman chose to ignore them and snuck out the back door of the White House.

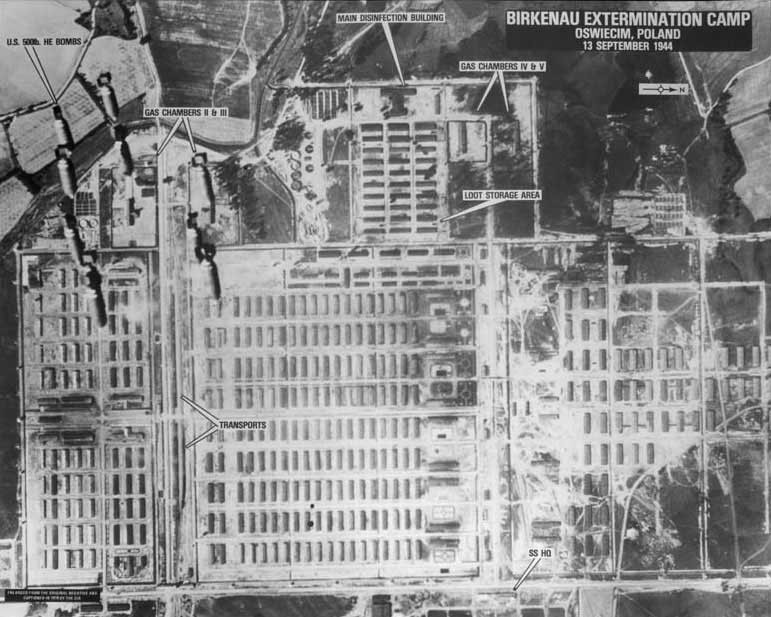

Pleas of Jewish leaders to bomb death camps were rejected by the War Office. Senior officials alleged the US military couldn’t spare precious aircraft and manpower for humanitarian missions to rescue Jews. Moreover, even if they did attempt bombing Nazi death camps like Auschwitz Birkenau and the approach rail system and bridges that might result in killing Jewish prisoners. This despite US aircraft were caught on film flying over the death camps to destroy the adjacent I.G. Farben artificial oil complex killing Jewish slave labor. Better to press on to victory and by doing so, save what remained of any Jews.

The problem is both the Burns film and a BBC 2020 documentary portrays there was division of opinion among Jewish groups about bombing Auschwitz. In reality, there was none.

To address the controversy spawned by the Burns film, The US and the Holocaust, we reached out to Dr. Rafael Medoff, founding director of the David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust, who had been critical of a 2018 US Holocaust Memorial Museum exhibit, Americans and the Holocaust that presented the same themes,

Jerome B. Gordon: I’m Jerry Gordon, senior editor at The New English Review and we have with us a friend of several previous interviews on this subject. Dr. Rafael Medoff. Dr. Medoff is the founding director of the David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies. He’s the author of more than twenty books, including America and the Holocaust: A Documentary History, The Jews Should Keep Quiet: Franklin D. Roosevelt, Rabbi Stephen S. Wise and the Holocaust and We Spoke Out: Comic Books and the Holocaust. He also writes for many publications, including, The Jewish Journal of Los Angeles. Dr. Medoff. Thank you for joining this discussion at a critical time.

Rafael Medoff: Thank you for having me.

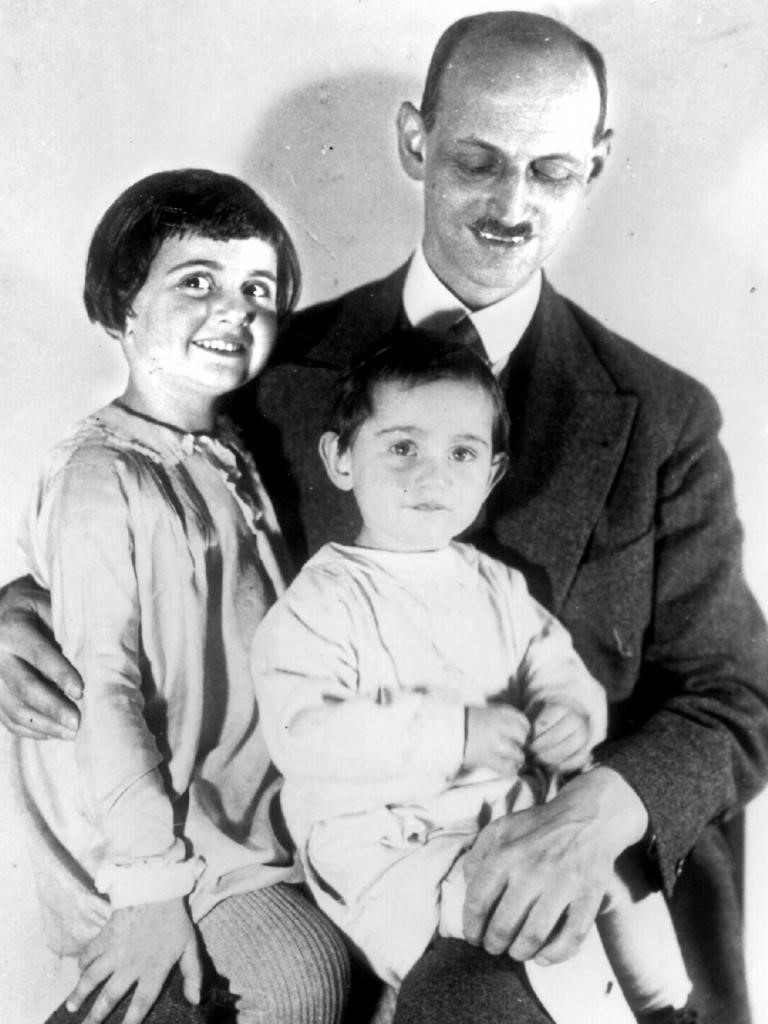

Jerome B. Gordon: Ken Burns’ PBS documentary The US and the Holocaust initial episode features pictures of Otto Frank and daughters Margot, and Anne Frank in Germany in 1933. Their family tried to immigrate to the US in 1941 but were turned away. Why did the Roosevelt administration keep them out? And how does Ken Burns portray it?

Rafael Medoff: Well, the way the story appears in the Ken Burns’ film, is that there was just too much paperwork and too many circumstantial problems, which made it complicated for the Franks to come to the United States. What’s missing from Ken Burns’ explanation is the fact that the American immigration quota for German citizens, which is what the Franks were, was almost never filled. For example, in the year that Otto Frank and his father applied for visas for himself and their family, which was 1941, the quota for immigrants from Germany to the US was about 47% filled. So that means that less than half of the available quota spaces were being used. And that’s because the Roosevelt administration had a policy, again, not explained in the Burns film. But it was a policy from the White House, which the State Department implemented to deliberately suppress refugee immigration below the levels that the quotas allowed. In 11 of the 12 years that Franklin Roosevelt was president, the German quota was unfilled.

And in fact, in most of those years, it was less than 25% filled. Unused quota places did not then roll over into the next year, they were simply discarded. So ultimately, more than 190,000 quota places from Germany were simply never used. That’s 190,000 German Jews who could have been granted haven in the United States without ever changing any of America’s immigration laws, simply if FDR had allowed the quotas to be filled. And unfortunately, that’s a major part of the story of America’s response to the Holocaust which is not explained in the Burns film.

Jerome B. Gordon: In contrast, notwithstanding the severe British White Paper restrictions on European Jewish immigration to Palestine, Britain let 250,000 Jews into that country over the years and more than 60,000 into the UK itself, including the famous Kindertransports. How does that compare with what the Roosevelt administration did?

Rafael Medoff: Well, when we compare how various countries opened or didn’t open their doors to Jewish refugees, it’s important to remember, it’s not just a matter of the numbers. This is not just a contest of statistics. But it’s also a question of what those countries were capable of doing. So, for example, in the case of Great Britain, and the United States, actually, the British admitted more Jews to England and to British territories than the United States did. But more to the point, the British did that despite the fact that they were directly in the path of Hitler’s aggression. And England is, of course, a much smaller country, Great Britain is a much smaller country than the United States. So, America was both at a much safer distance and was a much bigger country and was much more able to accept immigrants. So, the fact that the British authorities were more generous than the Roosevelt administration is striking.

That’s not to gainsay the fact that the British White Paper imposed on Palestine in the spring of 1939 was a cruel and unjust severe new restriction on Jewish immigration into the Holy Land. But the British did, over the course of the period we’re talking about—1933 to 1945—allow approximately 250,000 Jews into Palestine during the years when they most desperately needed a haven. During the years of the Holocaust, the British reduced Jewish immigration to Palestine to a tiny trickle—a maximum of 15,000 per year. So, let’s not go overboard in praising the British. On the other hand, it is a fact that they did take in 10,000 Jewish children on those Kindertransports; the United States did nothing similar. It also, by the way—Great Britain also took in 15,000 young German Jewish women as nannies and housekeepers, which saved their lives. So, although the British response, including its Palestine policy, left much to be desired, the Roosevelt administration’s policy was actually much worse and much less generous.

Jerome B. Gordon: When did the Allies learn of the Nazi SS Final Solution for Europe’s Jews, and how did they respond?

Rafael Medoff: Information about the mass killings of the Jews in Europe began trickling in soon after the onset of the Holocaust, in the summer of 1941. But during those first months, the information was fragmentary. It was sometimes difficult to corroborate, and many US government officials looked at that information skeptically and assumed that these were probably the same kind of random wartime atrocities that one can expect in any major armed conflict. It took a while—it took a number of months before it became clear in Washington that, in fact, what was happening was a systematic mass annihilation of the Jews in Europe through a sophisticated system of death camps with gas chambers and crematoria. Even though it took a number of months until that information became clear, nearly a year, one can say until the summer of ’42, nonetheless that was still several years before the end of the Holocaust. So, although the Allies did not learn of the so-called Final Solution immediately, they still learned about it and verified it, in plenty of time to have helped many of the Jews who became victims of the Nazis.

Jerome B. Gordon: Current off Broadway, a one-man production, starring American stage and film actor, David Strathairn. It’s called, Remember This: The Lesson of Jan Karski which has drawn new attention on the Oval Office White House meeting in 1943 of the Polish resistance courier and diplomat, Jan Karski, with FDR. What mission was Karski on behalf of Polish Jews? And how did President Roosevelt respond to Karski?

Rafael Medoff: Karski was a courageous messenger for the Polish Underground when Germany occupied Poland. The Underground wanted to send him to England and the United States in late 1942 in order to bring to those governments and to the public and the free world, news about what the Germans were doing to the Poles including the Polish Jewry. So, at one point before Karski was smuggled out of Europe, he was first brought by the Polish Underground to the Warsaw Ghetto. They sneaked him into the Warsaw Ghetto so he could see firsthand the atrocities that the Germans were committing. After that he was taken in disguise to a transit camp on the way to the Belzec death camp. And there, Karski again witnessed Nazi atrocities against Jews.

So, he was able to bear witness in a very important, direct way when he reached England, and then after that the United States. In England, he met with members of the press, members of parliament, and government officials including the foreign minister, Anthony Eden, all of whom expressed a general interest in what he had to say, but neither Eden nor other British officials took the information seriously enough to do anything about it. Karski then continued on to the United States. And in Washington, he met with a number of important officials. He also, again, met with the news media, Jewish leaders, but most significantly he met with President Franklin Roosevelt in July 1943.

Afterwards, Karski described in his memoirs his meeting with Roosevelt in considerable detail. And what he said was that Roosevelt was very interested in hearing details about the efforts of the Polish Underground and the general situation of Poland under Germany. But according to Karski, when he began to tell FDR details about the mass murder of the Jews, the president lost interest. And although Karski tried several times in the meeting to focus the president on this unique, unprecedented mass slaughter of the Jews in Poland, he could not get the president’s attention. And that was, frankly, typical of the Roosevelt administration’s response to the Holocaust throughout those years. The president was not very interested in the plight of the Jews. He did not want to do anything that would result in significant numbers of Jewish refugees possibly coming to the United States. And so, in general, the policy of the Roosevelt Administration was to do nothing and to claim falsely that nothing could be done.

Jerome B. Gordon: You’ve written a great deal about the activist group known as the Bergson Group. They were the ones who came up with the idea for the creation of the US government War Refugee Board. Why did FDR oppose creating such an agency, and why did he later give in?

Rafael Medoff: President Roosevelt’s guiding principle when it came to these matters was that he was not prepared to use any military resources for non-military purposes such as humanitarian goals, like helping Jewish refugees, or interrupting the mass murder that was going on in the death camps. So that was the overarching principle that the Roosevelt administration subscribed to. The specific idea of creating a government rescue agency was conceived by the Bergson activists precisely because they saw that neither the White House nor the State Department were taking any real interest in the plight of the Jews. So, the Bergson Group’s idea was that if there would be created a government agency whose entire purpose was to rescue Jewish refugees, then there was a chance that something could happen.

The Roosevelt administration insisted that there was no way to rescue the Jews, that the only thing that could be done was to fight the Nazis on the battlefield and win the war, and that would help the Jews. But as the Bergson Group and other Jewish advocates pointed out, if rescue was postponed until victory on the battlefield, then there might not be any Jews left alive to rescue. So, the Bergson Group began a campaign of public pressure and lobbying in Congress as a way to try to force Roosevelt’s hand.

In the autumn of 1943, to dramatize the need for a rescue agency, the Bergson Group, together with an Orthodox rescue group called the Vaad Hatzalah, organized more than 400 rabbis to march through the streets of Washington, pleading with Roosevelt to do something to help the Jews. This was a remarkable and unprecedented event because the Jewish groups had never staged a march to the White House. Many American Jews were nervous about the idea of making Jewish demands, especially in the middle of a war, and making demands of a popular president in such a visible and loud way. The Bergson Group, however, was led by non-Americans. Its main leaders were Zionist activists from Palestine and from Europe, and they were not as concerned about how the American public might respond to Jews organizing and making loud protests. So, they organized this march, three days before Yom Kippur, and it caused quite a spectacle. The president himself refused to meet with these rabbinical leaders, he snubbed them, slipped out a rear exit of the White House in order to avoid them. But there was very substantial news media coverage, leading members of Congress also greeted the marchers, and shortly after the march, the members of Congress introduced a resolution calling on the Roosevelt administration to create the special rescue agency.

The administration fought tooth and nail against this resolution. It did not want to devote any resources to helping Jews and it did not want to do anything that would result in large numbers of Jewish refugees possibly coming to America. So, the administration sent Assistant Secretary of State Breckinridge Long, who was in charge of the State Department’s Visa Division, to Capitol Hill to testify against the resolution. Long presented statistics that were wildly exaggerated, they were exposed in the press, and they backfired. What Long claimed was that from 1933 until that point, in 1943, 580,000 Jewish refugees had been brought to America. In other words, the claim was, “Look, look how many Jews that we, the Roosevelt administration, have rescued.” In fact, that number was a wild overstatement. That 580,000 was the maximum number of visas that could have been issued. The actual number that had been issued during that period was less than half of what he said, and not all of them were Jews or Jewish refugees. So, Long’s lies— there’s no other way to describe them—were soon exposed in the national press, which caused a great scandal.

The combination of the Bergson Group’s resolution and lobbying, and then Long’s wildly exaggerated testimony, created a kind of a political scandal for Franklin Roosevelt at the end of 1943 and going into early 1944. The Senate was poised to adopt this resolution calling for creation of a government rescue agency, and Roosevelt, now entering an election year, became worried about the possibility of an embarrassing political scandal in which the Congress would be asking him to rescue Jews and thereby highlighting the fact that he hadn’t even lifted a finger to help them. Right at this moment, it happened, that senior aides to the Secretary of the Treasury, Henry Morgenthau Jr, discovered that the State Department had been actually suppressing information about the mass killings and had also been obstructing opportunities to rescue Jews in Europe. These aides came to Morgenthau with the information, they wrote up a detailed report. Morgenthau brought that report to President Roosevelt in January 1944 and said to him, essentially, “If you don’t do something to head off the resolution Congress is about to pass, they are going to embarrass you. And all this information about what your State Department has been doing to block rescue is going to come out.” And Roosevelt, understanding the political calculations involved, decided it would be easier to simply throw a bone to the refugee advocates. And so, he unilaterally created the War Refugee Board, as they called it, through executive action, not waiting for Congress to force his hand.

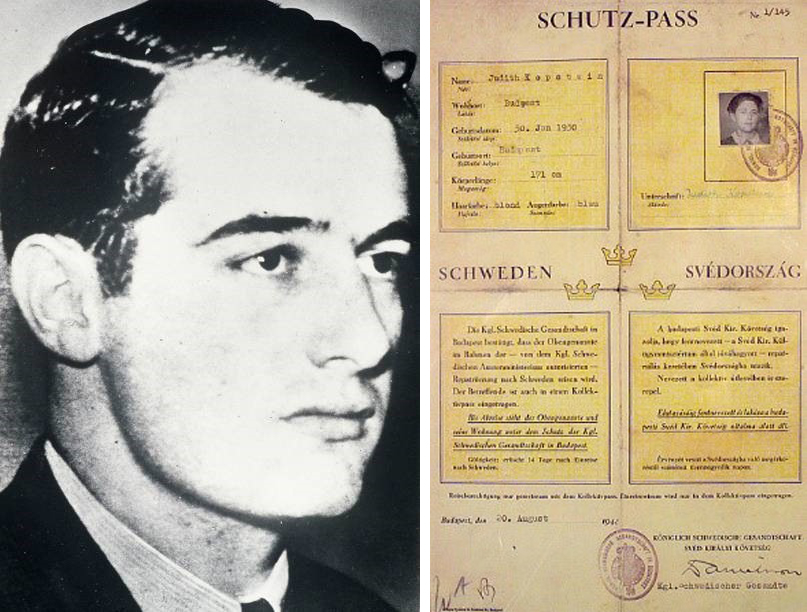

The War Refugee Board was fascinating for a number of reasons. First of all, Roosevelt gave it almost no budget. So, 90% of the board’s budget had to be supplied by private Jewish organizations. I don’t know if there’s another example in American political history where a government agency was almost entirely funded from private sources. But the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee and the World Jewish Congress provided most of its funds. Fortunately, the key leaders of the War Refugee Board were the same Treasury Department staff members who had first confronted Henry Morgenthau with the information about the obstruction of rescue. So those heroic whistleblowers became the heads of the War Refugee Board, and in the last 17 months of World War II, they did heroic work, sending funds to Europe to bribe Nazis into allowing Jews to escape. The funds were used to shelter Jews, and most important, the funds were used to sponsor the life-saving work of Raoul Wallenberg in German-occupied Budapest in 1944. Wallenberg, ultimately, as we know, ended up saving more than 100,000 Jews. And historians calculate that the activities of the War Refugee Board, including the work of Wallenberg, played a key role in saving the lives of about 200,000 Jews during those final months of the war.

Jerome B. Gordon: Over the initial objections of the president.

Rafael Medoff: There are those who, in retrospect—kind of diehard Roosevelt apologists—would like to give Roosevelt credit for the War Refugee Board, but the truth is, he was against it before he was for it. He did everything he could to stop it, but when there was no more real chance of stopping it, then he very reluctantly signed it into existence—but again, without giving it any significant support.

Jerome B. Gordon: In the spring of 1944, two escapees from Auschwitz, Rudolf Vrba and Alfred Wetzler gave Jewish leaders and allied diplomats, detailed maps of the camp, could that have been used to bomb Auschwitz?

Rafael Medoff: The report by the Auschwitz escapees, today historians call it “The Auschwitz Protocols,” arrived in the hands of American diplomats in Europe and others, right at the same time, that the Roosevelt administration was sending planes over the greater Auschwitz area to do reconnaissance in preparation for striking German oil factories, which were located in the industrial zone of Auschwitz. As we know, Auschwitz contained an area of mass murder machinery known as Birkenau. But then there was an area where the IG Farben factories were located where Jewish slave laborers—including by the way, a teenage Elie Wiesel—were put to work, creating synthetic oil for the German war effort. As a result, the Roosevelt administration considered those sites within the Auschwitz grounds to be legitimate military target. When Jewish groups, after receiving the information from the escapees began asking the Roosevelt administration to either bomb those gas chambers or hit the railways and bridges leading to Auschwitz over which hundreds of thousands of Hungarian Jews were being deported, the administration replied that it could not carry out any such bombings because it would be necessary to divert US bombers from far-away battle zones.

But as I’ve just noted, in fact, American planes were already flying over Auschwitz. And in fact, during the summer and autumn of that year, 1944, the Americans repeatedly bombed those oil factories, just a few miles from the gas chambers at the very same time that they were telling Jewish groups in America that they couldn’t reach the gas chambers, the railways, or the bridges, because their planes were nowhere in the area.

Jerome B. Gordon: Two years ago, the BBC released a documentary about the issue of bombing Auschwitz. For some reason, both the film and Ken Burns documentary completely omitted any mention of the most famous American connected to that issue that was former presidential candidate, Senator George McGovern. What was McGovern’s role?

Rafael Medoff: So, there are two important sources about this issue of the failure to bomb Auschwitz. One is the records of the many Jewish organizations and Jewish leaders who privately attempted to persuade the US to bomb the railways or the gas chambers. And then a second important source is the recollections of the pilots themselves who were flying over that area, hitting the oil fields. McGovern falls into that latter category. First, let me say something about the Jewish groups that were asking for the bombing of the railways. Altogether we know of about 30 different officials of Jewish organizations, including a few editors of Jewish magazines and newspapers, who were calling on the Allies to bomb Auschwitz or the railways. Most of those requests were directed to the Americans, to the Roosevelt’s administration, but there were also attempts to persuade the British and the Soviets.

In addition to those 30 officials, among whom was the chairman of the World Jewish Congress, Nahum Goldmann, there was also one official of the World Jewish Congress, A. Leon Kubowitzki, who urged the Allies to use ground troops rather than bomb Auschwitz from the air. He was in favor, of course, of bombing the railways. But specifically with regard to this idea of a precision bombing of the gas chambers, this Kubowitzki suggested that they shouldn’t hit it from the air because some of the bombs might accidentally hit prisoners in the camp and therefore, they should use ground troops. Well, so it was a division of opinion, but it was not really a division of opinion because there were 30 Jewish leaders urging the Allies to bomb from the air and one who thought they should use ground troops. Both the BBC and the Ken Burns film create a misleading impression that there was some kind of great divide among Jewish leaders on this question of bombing Auschwitz.

So, the first thing to say about this is even had there been a division on that question, there was no division about bombing the railways and the bridges. So that’s one thing. Second, as I’ve noted, there wasn’t a real division, it was 30 to one, but third, maybe most important, the Roosevelt administration had no interest in either Kubowitzi’s proposal for ground troops or the proposals from the other 30 Jewish leaders for air strikes on the gas chambers or the railways. The Roosevelt administration reached its decision not to use any military resources to help the Jews, well before the first bombing request even arrived. When we speak about the requests to bomb Auschwitz, they began in June 1944, but it was four months earlier, in February 1944, that the War Department established a policy, obviously with the approval of the president—the War Department didn’t make up its own policy—that it would not use any military resources to help the Jews.

And so, four months later, when Jewish groups first began asking to bomb Auschwitz or the railways, they simply took that decision, and they applied it. So, every time these 30 Jewish leaders or others called for these bombings, they simply were fed the same line— “No, we can’t do it because we don’t have any planes in the area. We can’t divert from the war for it to bring planes down there.” So, no matter what we think about what those 30 Jewish leaders proposed or what the one Jewish official said, it had nothing to do with what was actually happening. There was never any chance that the Roosevelt administration was going to accept those bombing requests. And part of the reason is because President Roosevelt was convinced that he had the support of the American Jewish community in his pocket, that there was no real danger that there would be a major protest movement by American Jews or that Jews might defect from the Democratic Party and vote for Roosevelt’s Republican opponent in November 1944.

He did not see the Jews as a serious political threat. And therefore, he saw no cost to turning down requests to bomb Auschwitz. And so, the tragic result is that the railway tracks could have been bombed just like the Allies were constantly bombing railway tracks in Europe during the war, but they were never bombed. In the Ken Burns film, just like in the BBC film, there are commentators who point out that railway tracks could have been quickly repaired. Well, two things about that. First of all, even if railway tracks could have been repaired after some hours, or a day, an interruption of the deportations of even hours or a day could still have made a life and death difference. But secondly, along those same railway routes, there were many bridges and when a bridge was damaged or destroyed, it took a very long time to repair. Sometimes they couldn’t be repaired. So, for that reason, the Allies were constantly bombing railway tracks and bridges throughout Europe during the war. They didn’t always hit them, they sometimes had to try repeatedly to knock them out, but they did. They just never hit the railways or bridges that the Jewish groups asked them to hit along the path leading to Auschwitz.

Jerome B. Gordon: I have a personal note on that. Firstly, there were two US Army Air Force complexes that were well within the bombing range of what we’re talking about. One obviously was down in Foggia, Italy from which McGovern and others undertook missions, and the other was where my late brother-in-law was involved with the logistics planning and operations and that was in Poltava in Ukraine. It was Stalin’s B-17 base, so to speak. The last point I’ll make is a personal one. A late friend of mine was one of the lead navigators on the bombing runs to hit the IG Farben plant. He verified not only the fact that the crematoria were ironically the way points for the final phase of those missions, but he also indicated that it would not take terribly much in the way of bomb loads to take those out.

Rafael Medoff: So now let me say a word about the role of George McGovern. McGovern, the longtime US Senator and 1972 Democratic presidential nominee, was a bomber pilot in World War II. He is unquestionably the best-known American witness—eyewitness—to this whole issue of the failure to bomb Auschwitz. A number of years ago, my colleagues and I at the David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies became aware of the fact that McGovern had been one of the pilots who bombed those IG Farben oil factories in the Auschwitz industrial zone. We sent a camera crew out to South Dakota to interview him, and the filmmakers Haim Hecht and Stuart Erdheim spent a long time filming an interview with McGovern about his recollections of this episode. I brought that to the attention of Ken Burns’ team, and the BBC team when they were working on their film, the fact that McGovern had done this interview, which is posted on the Wyman Institute’s website, Wymaninstitute.org. Yet neither the BBC film nor the Ken Burns film mentioned McGovern or included his important eyewitness testimony.

What McGovern said was that he and the other pilots were never told that there were death camps below, or that there were railway tracks leading to those death camps over which Jews were being deported. He said they bombed the oil factories and they certainly, in his opinion, could have bombed the gas chambers and the crematoria, and they certainly could have bombed the railways and the bridges. He said they were never asked to. He said if his commanders had asked for volunteers to take on the risk of flying those extra missions, he felt like—that a large number of the servicemen would have gladly volunteered to take on those missions. He said— because most Americans who served the World War II were fighting for idealistic reasons.

They understood it was a fight for freedom and democracy and for the humanitarian goals that the West represented as opposed to what the Axis represented. McGovern said that Franklin Roosevelt was his personal political—as he called him—his political idol. But, he said, even Roosevelt, in his opinion, had two major flaws. He said one was Roosevelt’s mass internment of 120,000 Japanese Americans, without any evidence that any of them had engaged in any kind of sabotage. And the second, he said, was the failure to have pilots like himself bomb the railways and bridges leading to Auschwitz or the gas chambers and crematoria themselves. So, McGovern’s powerful testimony really sheds a lot of light on this whole issue and on the possibilities that were never taken advantage of. And sadly, for no apparent reason, neither the BBC nor Ken Burns thought it was worth including even a few seconds of McGovern’s testimony in their films.

Jerome B. Gordon: What prompted your criticism of the BBC production, 1944: Should we Bomb Auschwitz?

Rafael Medoff: The BBC producers approached me and asked me to be interviewed, to be included in the film, but when they explained—in response to my questions—what the theme of the film was and who else they were interviewing, it was clear to me that they had set out with a goal which was not in line with the historical facts. In other words, they had an agenda. The agenda was to cast doubt on the idea that it was possible for the Allies to bomb Auschwitz. In the BBC film, they literally fabricated a scene in which they had Jewish leaders trying to convince American officials not to bomb Auschwitz because of the supposed risk to the prisoners. Not only is it absurd, in a so-called documentary, to have actors acting out a scene that never happened, but it also points to another remarkable aspect of this entire episode. The reason that the Roosevelt administration and the British refused to bomb Auschwitz had nothing to do with concern about civilian casualties. That’s something which defenders of FDR have made up in hindsight. But that’s not what happened at the time.

US officials never said, “We can’t bomb Auschwitz because we might accidentally kill prisoners.” In fact, which would be absurd because they were bombing those oil factories in broad daylight. I emphasize in broad daylight, meaning they knew that the factories would be filled with Jewish slave laborers, and they bombed the factories anyway. And in some cases, they killed or injured some of the workers. Similarly, that same summer, the American air force bombed a V-2 rocket factory that was situated at the Buchenwald concentration camp, again in broad daylight, when they had to assume that there would be prisoners nearby. And in fact, several hundred Jewish inmates of Buchenwald—the workers in that factory—were killed. But the Roosevelt administration regarded those targets as necessary military targets and therefore considered the deaths of those Jewish civilians to be a necessary price to pay. So, the idea that they didn’t bomb the gas chambers or the railways—in the railways there were no prisoners nearby—but even the gas chambers, the idea that they didn’t hit that target because of concern about harming inmates, that simply flies in the face of what actually happened in World War II.

Jerome B. Gordon: In a recent CNN documentary by Wolf Blitzer, he cited his father, David, who had, not unlike Elie Wiesel, prayed that the Allies would be bombing the railways and the bridges leading to the camp. Why did the Roosevelt administration reject this proposal?

Rafael Medoff: You know, over the years, I’ve had the opportunity to personally interview a number of Auschwitz survivors who were present there on those days when the American planes were bombing the oil factories. And they all said that they were praying for the bombs to fall, even though they knew that they might be hurt or killed. They all understood that Auschwitz was a mass murder facility, that there were all slated to be killed. So, they wanted the bombs to fall in the hope that it would slow down the mass murder process. Those survivors are a powerful group of eyewitnesses and Wolf Blitzer’s father David, is one of them. I had not known about his experience until the recent CNN special program hosted by Wolf Blitzer; his father’s story had not been publicized. David Blitzer had given an interview, an oral history interview, back in the early 1980s, but it was not something that had been publicized until the recent CNN special. As for the question of why the Roosevelt administration refused these many requests to bomb the gas chambers or the railways—well, as I say, the guiding principle overall was to never use military resources for non-military purposes.

However, it’s also true that there were many exceptions made. For example, the Roosevelt administration sent soldiers into a battle zone along the German-Czech border to rescue the famous Lipizzaner dancing horses. The administration also created an entire commission, starting in the summer of 1943, to rescue famous medieval paintings and other important cultural artifacts, and military personnel risked their lives to save those paintings. So, the question is, why is it that dancing horses and paintings were considered a higher priority than the lives of the Jews? And the answer, tragically, is that rescuing a lot of Jews meant being faced with the dilemma of where to put them.

President Roosevelt did not want large numbers of Jews coming to the United States. The British did not want large numbers of Jews trying to get into Palestine. So, taking an interest in saving Jews or interrupting the mass murder process created a political problem. It is not that any of the Allies wanted the Nazis to kill Jews. Certainly not. But they also did not want to take any action to rescue the Jews, because of the difficulties that would ensue. There, was an infamous quote by a senior British official when faced with pleas from Jewish groups to rescue Jewish refugees, who said, “What in the world will I do with a million Jews?” And that cruel line really sums up the callousness that characterized the response of the Roosevelt administration and its allies to the mass murder of the Jews.

Jerome B. Gordon: It’s interesting to me that your mentor Dr. David Wyman, who I had the pleasure of meeting with you several decades ago, had written extensively about the British wonder plane, the Mosquito De Havilland fighter bombers. There was one episode during World War II, where these, special air squadrons were used in Operation Jericho on February 18, 1944 to blow up the walls of a German prison in Amiens, France freeing French resistance fighters in the run up to the allied invasion in Normandy. This provided prima facia evidence that the allies had the capability of making precision attacks for humanitarian purposes.

Rafael Medoff: Yes. That raid on the Amiens prison in France is an interesting example, and not the only one, of successful precision bombing raids by the allies during that period. Now, the success of that particular raid was known at the time. It was in the press and Jewish advocates sent clippings about the bombing in France to US government officials, making this exact argument, “Doesn’t this show that a precision bombing of the gas chambers in Auschwitz would be possible?” But like all of the requests for bombing, the Jewish leaders were simply ignored or told “no” and given these disingenuous explanations about how it wasn’t feasible. Some of the letters from US government officials to Jewish bombing advocates actually claimed that a “study” had been done by the US government, which found that bombing the railways was not feasible—but no such study was ever done. Historians have been combing all of those relevant archives for many decades, and there’s no evidence any such study was done—but they simply said it. They said—US government officials said it, Jewish leaders had no way of disproving it. And it was a way of just pushing off the Jewish appeals until it was too late.

Jerome B. Gordon: What was the connection between the War Refugee Bboard and the heroic work of the Swedish diplomat, the late Raoul Wallenberg?

Rafael Medoff: Well, the principle underlying the work of the War Refugee Board was that if there was enough will, then a way could be found to rescue Jews. And this included the idea of sending rescuers into the heart of German-occupied Budapest in the summer of 1944. The War Refugee Board’s representatives in Sweden actually recruited Wallenberg, who had no previous experience in refugee matters. They recruited and convinced him to go to Budapest. They gave him the necessary papers. They gave him the funds needed to carry out his work and Wallenberg went. He went to Hungary and as we know, performed miracles, sometimes literally pulling Jews off of trains that were about to leave Hungary bound for Auschwitz. He saved many, many Jews and he’s properly recognized today, of course, as a great hero of humanity. His work would not have been possible without the work, the existence, the efforts of the War Refugee Board. And as we have noted, the very creation of the War Refugee Board was a result of lobbying by Jewish activists against an administration in Washington that did not want to rescue Jews and did not want to make any serious efforts—even though, ironically, Franklin Roosevelt had built for himself a reputation as a humanitarian, as the “champion of the forgotten man.” That was a famous slogan attached to some of his presidential campaigns, “champion of the forgotten man,” but the Jews—well, the Jews were forgotten.

Jerome B. Gordon: You’ve written a lot. And in fact, we just talked about the march of the 400 rabbis in Washington DC in 1943. Burns in his documentary, makes it seem like FDR’s Jewish advisors pressured him to snub the rabbis. Is that true?

Rafael Medoff: No. There was a circle of Jewish advisers around Roosevelt. Only a certain type of Jew could rise to that level in the Roosevelt administration—somebody who did not talk about Jewish concerns, who did not show any special interest in the plight of the Jews. We know of one important adviser and speechwriter for Roosevelt, Samuel Rosenman, who did, in fact, speak disparagingly of those marching rabbis and who recommended to Roosevelt on the day of the march that he should not meet with the rabbis. But we also know from the documents that the decision not to meet the rabbis had been made a week earlier. So, although it might be convenient to say, “Oh look, the Jews themselves didn’t want Roosevelt to meet the marchers,” in fact, the organizers of the march had sent telegrams to the White House the previous week, asking for a few minutes of the president’s time, so that several representatives of the rabbis could come to the White House and present their petition. And the petition, by the way, was asking for the creation of a government rescue agency.

So, a week before the march, White House aides sent messages back to the marchers saying, “No, the president is too busy. He can’t see them.” So, the decision clearly had been made well before Samuel Rosenman, Roosevelt’s chief Jewish adviser, said what he said to Roosevelt. Interestingly, this idea that the president was too busy to meet with the marchers, even for a few minutes—and their request literally said, “We only are asking for a few minutes”—that was a complete falsehood. We know that, because the president’s daily schedule is a matter of record and historians discovered it many years ago and saw that, on that particular day, October 6th, 1943, the president had a remarkably light schedule. He had, in fact, almost the entire afternoon clear, and that’s when the rabbis reached Lafayette Park, across the street from the White House.

So, the president had plenty of time. He could have spared those few minutes, but it was a political decision. He did not want to give these rabbis the credibility and attention that comes with a meeting with the president of the United States. For him to have spent a couple of minutes and receive their petition, would have been in effect saying that there was some legitimacy to their demands, and that is what Roosevelt wanted to avoid at all costs. The irony, however, is that although Roosevelt left the White House through that rear exit in order to avoid the rabbis, in fact he could not avoid the controversy because what happened is that the reporters who were across the street with the other 400 rabbis, saw that the President refused to meet with the representatives who had walked right up to the gate of the White House, hoping for a last-minute opening in the President’s busy schedule. The reporters saw what had happened, and they asked a number of the rabbis for their response.

Several of the rabbis were very critical of the President. This was very unusual for American Jews in 1943. Jews did not publicly criticize Roosevelt. First of all, the Jewish community was genuinely supportive of the president, of his party, of the New Deal, but also, they were nervous about the idea of seeming to be challenging the highest authority in the land. But some of the rabbis were so disillusioned by the refusal of the president to accept their petition, that they told reporters that they felt the president gave them the cold shoulder and that ended up being front-page news in the Washington, DC press and in other newspapers. And so, the controversy that Roosevelt had hoped to avoid in fact turned out to be the controversy that he provoked. And that widespread news media coverage in the days following the march helped galvanize the members of Congress, whom I mentioned, who then introduced the resolution calling for creation of a government rescue agency.

Jerome B. Gordon: About 1,000 European refugees, perhaps a predominant number of whom were Jews who had escaped from Nazi imprisonment, were sent to the United States in August of 1944. Who brought them? Where did they end up?

Rafael Medoff: This particular episode is actually connected to another very important and misleading theme of the Ken Burns film. In Burns film, the viewers are told again and again that the American public was staunchly against allowing in any more immigrants, especially Jewish immigrants. And they cite a number of polls, public opinion polls in the ’30s and into the early ’40s, which showed strong public opposition, there was also strong Congressional opposition. But the crucial fact that the film does not explain, is that public opinion shifted very significantly during the course of the war and later in the war, there was a change in public opinion, which was in fact documented by a very important poll. In the spring of 1944, when the War Refugee Board got kicked into high gear, one of its first projects was to try to convince President Roosevelt to grant what they called free ports or temporary havens for refugees, to allow Jews to come in, but only temporarily, not as permanent immigrants, but just to come in for the duration of the war.

Roosevelt decided he wanted to see what the public would think about that, so the White House privately commissioned a Gallup poll asking about this specific question, taking in refugees temporarily. And the result was that 70% of the American public said they would support bringing in an unlimited number of refugees temporarily until the end of the war. So, the president knew that he had substantial public backing to bring in many refugees, starting in the spring of 1944. This is a very important part of the story and the explanation of it was completely left out of the Ken Burns film, apparently because it contradicts the running narrative that Burns has constructed, this idea that the public was so opposed to immigration that Roosevelt’s hands were tied. Well, starting in April 1944 there was no basis to say his hands were tied, the Gallup poll proved exactly the opposite. Sadly though, even though FDR knew 70% of the public would support an unlimited number of Jews being allowed in, he agreed to only one token shipment of 982 refugees. And in fact, the president specifically instructed the army personnel on the ground in Italy not to bring over all Jews, but to include a number of non-Jewish refugees. Ultimately, about 90% of that group of 982 were Jews.

They were taken to an abandoned Army camp in Upstate New York in the town of Oswego, and they were able to stay there, and their lives were saved, but so many more could have been brought over. There was plenty of room on ships returning from Europe, because when the US government sent over troops and weapons on so-called Liberty ships, those ships returned empty. In fact, they had to be loaded down with rubble from bombed-out British cities like Bristol, because otherwise they would have capsized, that rubble known as ballast kept the ships afloat. They could have brought Jewish refugees as ballast to keep those ships afloat on their return trip to America. So, there was no shortage of transportation and there was no shortage of public support, it was a decision by President Roosevelt to bring in as few Jewish refugees as possible. Because it was an election year, he wanted to bring in one small group to make it seem as if he cared and he was a humanitarian, and he hoped that would be enough to keep therefore any scandal from erupting, but that was it. That one, tiny, sad group of 982.

Jerome B. Gordon: Before we adjourn, I want to ask you an opinion question. You and I have looked at and you’ve been critical of a previous exhibit by the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, I think it was launched in 2018. Now we have this documentary by Ken Burns laden with defects, in terms of what the true story is. Why is this occurring at this time? Why isn’t truth-telling prevailing?

Rafael Medoff: It’s not a coincidence that Burns’ film has many of the same flaws as that exhibit at the Holocaust Museum. The reason is because when that exhibit was created five years ago, its running theme was to minimize President Roosevelt’s responsibility for the abandonment of the Jews. And so, the exhibit, for example, cuts out that poll, the 70% Gallup poll that I just mentioned. The exhibit misrepresents the question of the bombing of Auschwitz and in many other ways, that exhibit called “Americans and the Holocaust” deliberately downplays FDR’s role and makes it seem as if the State Department was somehow guiding American foreign policy. You could look at that exhibit in the Burns film and come away thinking that Breckinridge Long was the President and not Roosevelt. As if Long and the other State Department officials were making up their own policy. The State Department never makes up its own foreign policy, it implements the policies of the President. That’s true today, and it was true then, it’s always been true.

Burns has said that the Holocaust Museum approached him several years ago and asked him to make a film based on the exhibit. So, apparently following in the footsteps of the exhibit, Burns also has created a film which distorts and minimizes FDR’s role. It’s not as if Burns was ignorant of what historians have discovered about Roosevelt’s abandonment of the Jews. I, myself, sent him copies of my books and other information years ago to acquaint him with what the historians from David Wyman and on down have found. Yet he chose instead to create a highly politicized film, which tries to rescue FDR’s image, in effect, just as the Holocaust Museum—for whatever reason—has likewise made a decision to pretend as if the State Department was in charge of American policy. And FDR, whom we all revere as a strong and decisive leader—he led us out of the Great Depression, and he led us to the brink of victory in World War II—this determined, strong leader suddenly is treated in the Holocaust period as if he were some kind of a helpless prisoner of public opinion or of the State Department. But there were so many opportunities that Roosevelt could have taken advantage of to help the Jews—whether it was simply allowing the immigration quotas to be filled; allowing planes that were bombing the Auschwitz oil factories to hit the railways nearby; using those empty Liberty ships to bring refugees back; or bringing in refugees temporarily with the backing of 70% of the American public. There were so many things that could have been done at the time, yet Roosevelt chose not to do them and sadly, some diehards today want to whitewash that and present him as some kind of a weak president who was unable to make his own policies and simply went along unknowingly with these evil actors in the State Department. This is not to excuse, in any way, Breckinridge Long’s abhorrent behavior and the other actions by officials of the State Department to suppress Jewish immigration, but we know from the documents that they regularly briefed President Roosevelt on what they were doing to block immigration, and he gave them his full approval.

Jerome B. Gordon: Dr. Medoff, where can our readers find more about the Institute’s investigative work on the Holocaust?

Rafael Medoff: The website of the David Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies is wymaninstitute.org, W-Y-M-A-N institute.org.

Jerome B. Gordon: And where can we find many of your published books?

Rafael Medoff: They’re available on the website of the Wyman Institute, as well as all the usual places that you buy your books.

Jerome B. Gordon: I want to thank you for this timely, engrossing and highly informative interview on the defects currently being unleashed on the American public in Ken Burns documentary on “The US and the Holocaust.”

Rafael Medoff: Thank you so much for inviting me.

Watch this discussion with Rafael Medoff.

Jerry Gordon is a Senior Editor of The New English Review, author of The West Speaks, NERPress, 2012 and co-author of Jihad in Sudan: Caliphate Threatens Africa and the World, JAD Press, 2017. From 2016 to 2020, he was producer and co-host of Israel News Talk Radio-Beyond the Matrix.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast