Truly: A Story in Three Parts

Part Three

by James Como (May 2023)

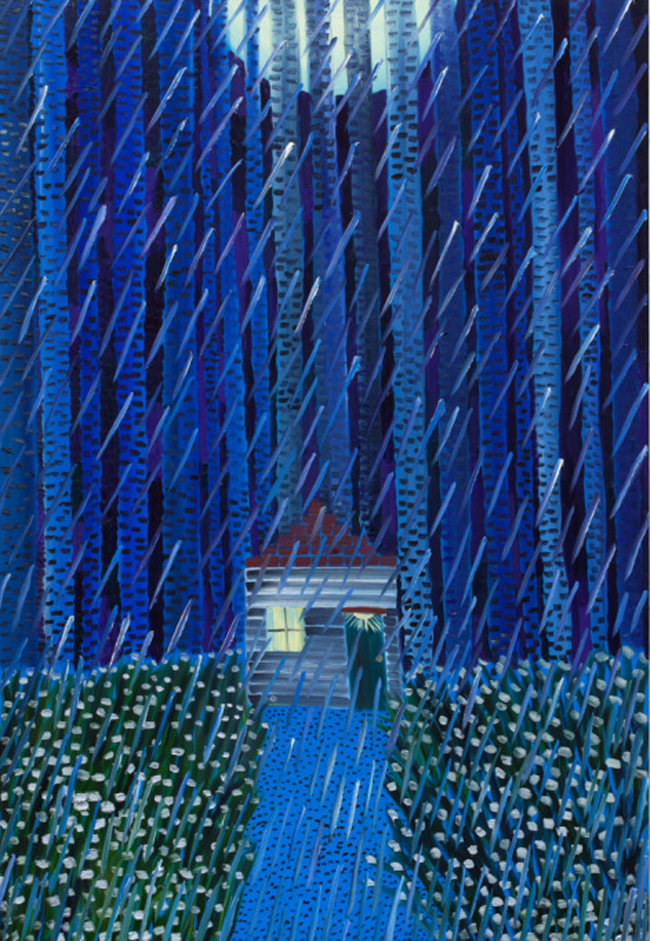

Starry Night, Matthew Wong, 2019

Adelaide worked as an assistant librarian, Col as a student aide enrolled at Baruch College, where he studied business. He was already investing in the stock market and doing pretty well. Truly had a part-time appointment as a college laboratory technician, and Jozef picked up work as a translator for the Russian, German, and Polish consulates. Together they managed and were happy. Jozef usually won at Scrabble, Col at Monopoly, and Truly at any trivia board game. Somehow, though, when they watched Jeopardy together it was Adelaide who came up first with the right question. Needless to say the young folk were puzzled.

It was raining softly and Jozef and Truly were lying abed contentedly, shoulder-to-shoulder, after another try at giving Col the nephew or niece he wanted. Their bed was next to the window, which was opened ever-so-slightly, so they could feel the coolness. Streaks of street light played on the ceiling, and they watched. And they listened. Both heard the night sound, from so many tissues of time, voices distinct, calm, clear.

When their hands touched they were gently tossed, as though on a bed sheet waving in the wind. There was melancholy, then great sadness, then curiosity. Concrete memories from very early childhood followed, then abstractions followed by formulae. They looked at each other and smiled.

“We are one body now, you know, Truly.”

“I do. But not one mind, right?”

“Right!”

They moved from one transparency to another at will, sometimes passing right through, or simply jumping to one that passed through the one they were already on. Places, periods, dress, customs, events passed—not passed by but passed through them, as though all history, memory, mood, scientific knowledge, philosophy and literature were coming from within. Still the sound was calm and distinct and somehow beckoning.

Then they were in light, dim at first, then bright, sunrise. They could see and hear and feel each other, and they could smell the sweetness of dawn—their bodies glistening like columns of silver. Each turned to look at the other and saw something like a personality. Not a body but a flavor, or a group of flavors. There was courage, tenderness, intelligence, imagination and absolute love. Each had become a sort of adjective, pure quality.

“We are in the realm of spirit now,” Jozef whispered. “Neither time nor space, neither height nor length but depth.” They turned to each other and embraced until Truly asked, “who is that?”

Approaching them was—not exactly a figure but a sketch with colored lines.

“I think that’s a dream,” Jozef answered.

“And around us is sleep?”

“And under us are the stars.”

They looked at what they thought was the ground but what they saw was nighttime dotted with brilliant points of light.

Floating next to the dream were clouds shaped like people.

“Maybe we’ll meet an angel or two.” Jozef was gazing all around.

They realized that each had a fruit, he an apple, she a pear, so they ate, not having realized how hungry they were. It was as thought each tasted the particular fruit for the very first time. Pure appleness, pure pearness. They each now understood the fruit for the first time.

“Now, I wonder what the wind really is,” Truly muttered.

Jozef looked at his love. The sun had set, and the full moon seemed to be right next to them.

Standing in front of the moon, in silhouette, were three figures, a tall man, a shapely woman, and a shorter fat man. Even without seeing their faces, Truly knew them as the first people she had met, under the lamp post, years ago.

“There she is again,” the tall man said. “And we’re not dreaming this time,” the fat man added. The woman said, “she’s brought a friend.” “Are we sure it’s her?” asked the tall man, “she’s bigger now. Wasn’t she a girl last week?” And then they were gone.

Jozef looked at her, then at yet another figure. “Who is that, Truly? He’s looking at you with such, such— ”

“Yes, oh yes! Poppa!”

“Truly, that’s the professor, Professor Sapiens.”

They looked at each other, then turned back to the figure, But he was gone.

“We must return, Truly. The fabrics of times and spaces, of moods and minds, of events, places and people—we’ve been allowed to know them, in our limited way, but we are not meant to inhabit any but our own.”

Truly rose, pulled Jozef up, and, holding hands tightly they ran together, until they were in their bed, the rain falling, the clear sound rippling through, the dawn on its way but not yet breaking. Both were out of breath.

“Jozef, tomorrow we must take the bus. Promise me.”

“I don’t think we should, Truly, but if that’s what you want, then … ”

***

The next day was Saturday. Col prepared breakfast and surprised everyone. No sausages, no eggs. Just biscuits, bagels, croissants, a variety of jellies and plenty of butter, yogurt and sliced fresh fruit, with fresh grapefruit juice and coffee. And what he called crème fresh. “They call this a Continental Breakfast,” he declared. “I saw it on a cooking show. Well, actually a travel show. A lot of it is from scratch. Well, not exactly from scratch but from mixes that I had to mix and bake.”

There were congratulations and thanks all around. “So, investment banker or chef?” Truly asked. “Entrepreneur,” Col answered. “A chain of really class restaurants.” Truly said, “but Col, can chains be classy?” “With our mother managing them they’ll be nothing but class.” By the end of breakfast there was no food left on the table. Jozef said, “Col, why don’t you and I clean up.” But Col answered, “no thanks, brother-in-law. That’s on me. You go take my sister for a, uh, an early nap.”

Adelaide chuckled at that. Truly, blushing, her head tilted to one side, said, “I think a walk would be nice.” And so Jozef and Truly hugged Col, kissed Adelaide, and left. “Col, too obvious, and none of your business!” But Adelaide was thinking the same as Col.

Truly and Jozef walked towards the park hand in hand. “Tell me,” she asked, “why are you hesitant about riding the bus?”

“We went inside, Truly, and that’s where eternity lies. And whether we knew it or not, we were on our way. There’s no return. Here is the world of shadows. When we are inside we get closer to the what’s real, the opposite of a black hole, including to what is real about ourselves, our intellect, imagination, will, and even our soul. We would want to stay, to see the monstrous, the angelic, the mythological, all folk and faierie lore. It would be too exciting every to leave.”

“Is God there?”

“God is everywhere, except in sin, Truly. But your mother and brother aren’t.”

“But my father said it’s all a two-way street.”

“Yes. Like marriage, and family, and the exterior journeys that we’ve taken. But the interior travel … ”

“Is it who we might meet?”

“In part. You might meet yourself, and that could lead to destruction. We don’t know.”

“Anybody else?”

“Yes. You know. We saw your father. He had told me in class to beware. His appearance indicates to me that Loki is prowling.”

“But not on the bus, Jozef. That would be external and— ”

“Would it stay that way?”

“Jozef. Just once. I want to nail down my time-space-spirit theory, and if that involves Loki, so be it.”

From their room they heard the rain and the night sound. Once at the sidewalk they waited. Slowly the bus pulled up. Some people got off: their normal stop. Only they got on. The bus then rose off the street and began to twirl like an amusement park ride.

“This is time,” they heard one voice say. Another whispered, “and space.” A third declaimed, “and God.”

Inside the bus was bright, outside there was only darkness. “And you,” a fourth voice cackled. And that same voice creaked, “it is a one-way street.”

“Existence has no certainty, no gravity, no space or time. No mass. Only energy.” It was the third voice. And the fourth, creaky voice whispered, “you’re never going back.”

“God is always two-ways,” Jozef shouted. “He comes to us, brings us to him, if we allow it.”

Together the voices chanted, “there is nothing. There is no God. You are nothing.” And then Jozef and Truly saw the stages of their lives, from infancy, to childhood and adolescence, into adulthood, to the present. “Those will haunt you always,” chanted the voices. Happiness will fade, failures will remain. Until you are nothing, not even memories.”

The bus now seemed to be spinning, though slowly. They could not tell. Without gravity or space there was no way to know. “You are two dots, smaller than electrons but with less energy. You are not.”

“I am!” Truly was shouting. “I— ”

“Hah!” the four voices cackled together. “There is no ‘am’ —or ‘is’ or ‘was’ or will be’. Not even a ‘never’. You are nothing.”

And Truly screamed, “I am Truly! Truly I am! Truly!”

She grabbed onto Jozef, who seemed asleep. She struggled mightily to get to the door of the bus.

“Oh, you would leave Loki only to meet Loki? Go ahead then. Jump!”

At that moment the back door of the bus opened, and Jozef, now awake, said calmly, “it’s fine, Truly, it is fine. Together we take the step.”

And from the front of the bus the driver said, “you are the rock, Truly, and Truly you are free. Jump!”

At first, after their first step out, they seemed to float. Or were they? They might have been falling—or rising. They held tight to each other, face to face, and they both knew there was nothing better to do than to kiss, so they kissed.

***

“Come on, lazy bones,” Adelaide spoke through the closed door. “Breakfast. Then church.”

Col had made French toast, scrambled eggs and—sausage. A lot of them. After saying a short grace, led by Truly, Col, smiling broadly, said, “why Sis, you are absolutely glowing this morning.”

Ignoring her brother, Truly primly said, “Mother, would you pass the sausages please?”

“She means again, mother.”

“That’s enough, Col. Sweetheart, Truly, you eat as much as you please. We’ll walk to church.”

After church, Jozef and Truly walked to the park. The fall colors were full, full of greetings. “Hello, yellow,” Truly said. “We love you, purple,” Jozef added. Well, once such fun begins it takes on a life of its own. The bushes, flowers, trees, clouds, and wind got their greetings too.

They walked on in silence until Jozef said, “your brother knows something, doesn’t he?”

“Well, yes. You know he’s a senior now, so he’ll be getting a nice graduation present come May.” They both laughed at that.

Come that May, Edward Colin was born, and Col became the most attentive baby-sitter imaginable. Jozef and Truly were on their way to teaching and research careers, respectively. Within five years, Col, who had made good money in the stock market, opened Breakfast and Brunch. His mission in life seemed to be to teach four-year-old Eddie the secrets of sausage-eating.

The next year the Yale University Press published Science is Theology by Truly Ratomski and Jozef Ratomski. It argued that the Divine Mind keeps time and space in place as we know it, but that with meditation and conviction a person could “travel the many planes into the realm of quantum spirit.” It warned against the ‘black holes’ of the intellect and imagination. The most controversial feature of the book was its discussion of the ‘Loki Factor’, which some critics called ‘fascistic.’ The book was short-listed for the Pulitzer Prize for general non-fiction.

Little Eddie, careers, reputations and prosperity all grew, but the family stayed put, comfortably, happily. Always Truly and Jozef listened in the night, especially when it rained, but they didn’t travel – not until perfect strangers began to show up at work, in the lab, and even near home, sometimes two or three at a time.

One day, while out for a stroll with Eddie, four of those strangers surrounded them, telling them to come along, that they needed help, that the bus was on its way. One of them put his hands on Truly and Jozef punched him so hard the stranger fell to the ground. At that, the other began to grab the three of them.

That’s when they all heard a soft but firm female voice. “That would be a mistake, you ugly bugs.” And there was the shapely woman from the pool of light. When the thugs looked at her, the short muscled man grabbed two muggers, smashed their heads, and down they went. The thin man looked down at them and said, “let’s all go back where we belong, shall we?”

As they began to disappear, Truly said, “thank you” and Jozef said, “if ever you need us —” But the travelers were gone. “Is it over?” Truly asked. Jozef answered, “let’s take the bus tonight.”

Once on the bus they saw the world flip and twirl, come close and then zoom away. Day followed night very quickly then night returned. But there was no sound. When the bus stopped they stepped off.

They were on Jozef’s old childhood street, except there was the huge rock he would visit with his grandmother, right there instead of in the park. And there standing by it was a sloppy old man, short and skinny, unshaven but with piercing gray eyes.

“I am the Gestapo,” he sneered, “and the KGB, and— ”

“You are nothing,” said Jozef calmly, and at that point Truly was prouder of him than ever. “You are an emptiness. A mere hole.” Then, turning to Truly, he asked, “what shall we do with him, love?”

“Why, what one does with any hole. One fills it in. Please wait here, husband. I won’t be long.”

As Truly began walking towards the figure, the world began to be drawn into it, so that everything around them began to shrink and disappear. “Come,” he commanded, “come into me.”

Truly did not stop, or even change her pace, but still walked towards him. “I am Truly, that’s who I am. Truly I think and feel and imagine. And Truly I do I love.”

The figure trembled, and the world stopped disappearing into him. Then he stretched out his arms and looked up. The stars and the moon sunk into him, ages past, too. Planets, whole galaxies, and people did he swallow.

But still Truly did not stop. Then, face-to-face, Truly said, “enough theater, Nothing. Now, swallow yourself. And he was gone, and the cosmos were restored. Jozef took Truly’s hand and they kissed. They saw the bus and boarded, and off they went.

***

Adelaide died peacefully in her sleep, without becoming a great-grandmother but having seen her Little Eddie get his own Ph.D., in Comparative Literature. He and his father would have a weekly Quotation Challenge. Col built a chain of restaurants and became a celebrated chef, brunch his specialty. And all along Truly and Jozef slept in their original matrimonial bed. As it happened, they had no more children, no matter how sweetly they tried.

Every now and then they would go to the window and look at the pool of light, where their three friends would be sharing a break before going back on set as extras in this movie or that. When the bus stopped, as it did from time to time, the driver waved to the lamp post friends, who waved back. Then he waved to Jozef and Truly, who would say, “I love you poppa.”

Those raindrops are us, they knew, sliding along the transparencies of time, and if you listen closely you will know that night sounds differ from day noise. They come from everywhere, casual, friendly.

Table of Contents

James Como’s new book is Mystical Perelandra: My Lifelong Reading of C. S. Lewis and His Favorite Book (Winged Lion Press).

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast