by Jeff Lipkes (August 2018)

Starry Night, Edvard Munch, 1893

A moetotolo, or “sleep crawler,” is a digital rapist. He enters the home of a young woman in the early morning hours and attempts to insert one or two fingers into her vagina before she’s fully awake and able to resist. This was once a venerable tradition in Samoa; it was based on the ceremonial deflowering of a taupou, a high-caste virgin.

Margaret Mead was nonplussed when she was told about the practice soon after she began her research on Manu’a in 1925. She had to mention it; the custom had been reported by Western travelers since the early 19th century. Mead decided that the sexual assault added “zest to the surreptitious [consensual] love-making which is conducted at home.” (Mead 1928, 95) The girl, after all, was probably expecting a lover and may “indiscriminately accept any comer.” (No pun, presumably.) Mead also attempted to blame the victim. “The Samoan girl who plays the coquette does so at her peril.” (Mead 1928, 94) The moetotolo was often acting out of revenge for having been stood up.

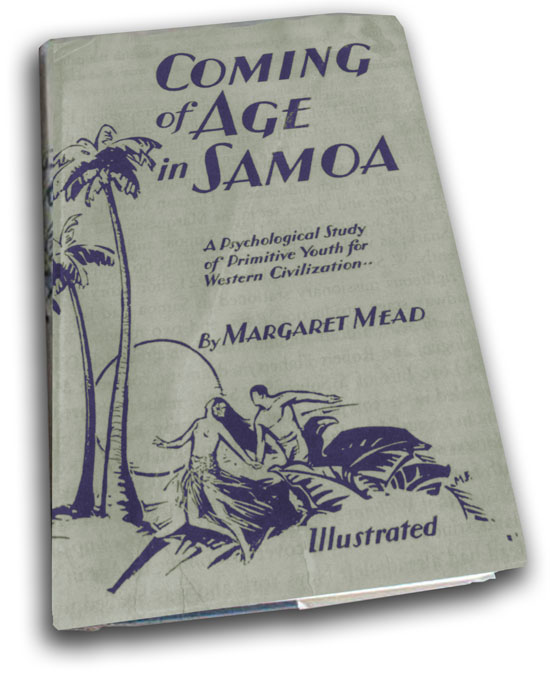

Coming of Age in Samoa was published 90 years ago this September. Assessing the influence of any book is hazardous, but there can be no question that Mead’s bestseller helped transform American attitudes toward sex. By 1968, the annus mirabilis of the sexual revolution, the book had been reprinted 14 times, and was selling nearly 100,000 copies a year. (Freeman 1999, 1919, 199) It was routinely assigned in introductory anthropology classes.

Coming of Age in Samoa was published 90 years ago this September. Assessing the influence of any book is hazardous, but there can be no question that Mead’s bestseller helped transform American attitudes toward sex. By 1968, the annus mirabilis of the sexual revolution, the book had been reprinted 14 times, and was selling nearly 100,000 copies a year. (Freeman 1999, 1919, 199) It was routinely assigned in introductory anthropology classes.

If Coming of Age helped launch the sexual revolution, it was also the Magna Carta of multiculturalism. Its unsubtle subtitle was “A Psychological Study of Primitive Youth for Western Civilization” and the book hammered home its message in the last two chapters, “Our Educational Problems in the Light of Samoan Contrasts” and “Education for Choice.”

Admiration for the “noble savage” pre-dates Rousseau by more than two millennia. It has been traced back to Homer, who was “inclined to believe that the most remote peoples were the best.” (Lovejoy and Boas 1935, 288) Tacitus, de la Casas, Montaigne, Montesquieu, and countless others offered invidious comparisons between calculating, ambitious, affected, and hypocritical Europeans and the spontaneous, generous, honest, and kind non-Westerners they conquered and exploited.

But Mead presented herself as scientist, or at least an anthropologist. She also redefined what was noble about the savage. He had never been admired for his promiscuity. Quite the opposite: the mythical savage was purer, more faithful, more monogamous than the European. Mead turned this formula on its head, making his chief virtue the absence of what had come to be considered, and despised, as middle-class morality. Happiness had begun to replace nobility of character as a desideratum, and the Samoans were happy because they were laid back. Americans were unhappy because they were repressed.

In contrast to Westerners, a Samoan child learns that “sex is a natural, pleasurable thing; the freedom with which it may be indulged in is limited by just one consideration, social status. Chief’s daughters and chiefs’ wives should indulge in no extra-marital experiments.” (Mead 1928, 201)

Lovemaking, as Mead wrote in a follow-up study, is “the pastime par excellence.” “Sex is play, permissible in all hetero-and homosexual expression, with any sort of variation as an artistic addition . . . Love between the sexes is a light and pleasant dance.” (Freeman 1983, 91-2) “Romantic love,” she assured readers of Coming of Age, “as it occurs in our civilization, inextricably bound up with ideas of monogamy, exclusiveness, jealousy and undeviating fidelity[,] does not occur in Samoa.” Samoans “laugh at stories of romantic love, scoff at fidelity to a long absent wife or mistress, believe explicitly that one love will quickly cure another . . . Adultery does not necessarily mean a broken marriage.” However, when partners do agree to separate, “divorce is a simple and informal matter.” (Mead 1928, 104-5, 106, 108)

Casual sex is approved of because of “the general casualness of the whole society. For Samoa is a place where no one plays for very high stakes, no one pays very heavy prices, no one suffers for his convictions or fights to the death for special ends.” (Mead 1928, 198) And no child is left behind: “No one is hurried along in life or punished harshly for slowness of development. Instead the gifted, the precocious, are held back, until the slowest among them have caught the pace.” (Mead 1928, 198-9)

Coming of Age was the first book published by William Morrow, and he marketed it cleverly. On the cover was a drawing of a bare-breasted young woman leading her lover to a tryst beneath a palm tree, illustrating the lurid opening description of Chapter II, “A Day in Samoa.” Morrow also secured a blurb from the leading crusader for free love, Havelock Ellis. Coming of Age, he wrote, was “not only a fascinating book to read, but most instructive and valuable.” (Howard 1984, 127)

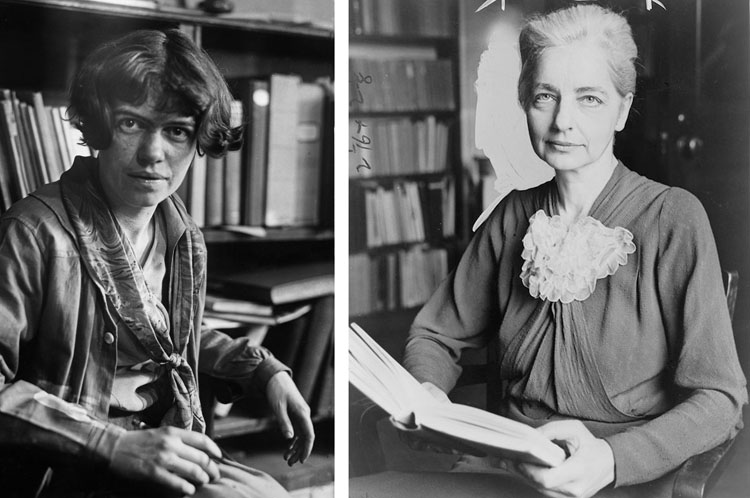

Margaret Mead was just twenty-three when she arrived in Samoa, and it’s not hard to see why she would want to celebrate a paradise in which “free experimentation was permitted” and it was a “rarity” when “both lovers are amateurs.” (Mead 1928, 150) She had married Luther Cressman after graduating from college, but had already had affairs with two anthropologists, Edward Sapir, seventeen years her senior, and her mentor Ruth Benedict, fifteen years older than she, and homosexual affairs with girls her own age. According to Derek Freeman, who had sworn testimony, Mead also had an affair with a young, profligate Samoan man, Aviata. (Caton 1990, 318) On the return voyage, she fell in love with fellow passenger Reo Fortune, who she married two years later. She eventually divorced him and married Gregory Bateson, who she also divorced. Reverting to lesbianism, she then had a long romantic relationship with still another anthropologist, Rhoda Métraux.

Margaret Mead was just twenty-three when she arrived in Samoa, and it’s not hard to see why she would want to celebrate a paradise in which “free experimentation was permitted” and it was a “rarity” when “both lovers are amateurs.” (Mead 1928, 150) She had married Luther Cressman after graduating from college, but had already had affairs with two anthropologists, Edward Sapir, seventeen years her senior, and her mentor Ruth Benedict, fifteen years older than she, and homosexual affairs with girls her own age. According to Derek Freeman, who had sworn testimony, Mead also had an affair with a young, profligate Samoan man, Aviata. (Caton 1990, 318) On the return voyage, she fell in love with fellow passenger Reo Fortune, who she married two years later. She eventually divorced him and married Gregory Bateson, who she also divorced. Reverting to lesbianism, she then had a long romantic relationship with still another anthropologist, Rhoda Métraux.

Unfortunately, as Freeman detailed in two books, Mead had written a work of fiction disguised as an anthropological monograph. His most sensational finding was that she relied heavily not on testimony of adolescent girls, but on a sixty-sixty-year old half-Samoan widow, Phoebe Parkinson, “with singular gifts as a raconteur,” Mead admitted, and, especially, two Samoan friends her own age, Fa’apua’a Fa’amu and Fofoa. The two young women deliberately mislead her. “We were just joking,” said Fa’apua’a, in sworn testimony. “She must have taken it seriously, but we were only joking.” (Freeman 1983, 252; Freeman 1999, 3)

Mead’s field notes are the smoking gun. They reveal, writes Freeman, that “the sexual behavior of the adolescent girls she had selected for study was never systematically investigated.” (italics Freeman’s)(Freeman 1999, 158) The American anthropologist Martin Orans, who also examined the notes, concludes that Mead’s research was “seriously flawed . . . filled with internal contradictions and grandiose claims to knowledge that she could not possibly have had.” He is incredulous that her book “could have formed the basis for an illustrious career,” and disturbed that “virtually none of the numerous reviews of the Mead-Freeman controversy point to the profoundly unscientific nature of her work.” (Orans 1996, 132)

But then Margaret Mead, fresh from Greenwich Village, was more interested in giving the finger, metaphorically, to the middle-class values Max Weber found perfectly embodied in Mead’s fellow-Philadelphian Ben Franklin: sobriety, thrift, self-discipline, self-denial. As Lowell Holmes, the anthropologist who did a follow-up study of Samoa wrote, “Margaret finds pretty much what she wants to find.” (Caton 1990, 316) Sapir was more dismissive. “She’s a pathological liar,” he told a graduate student. (Caton 2006)

Even before Freeman and Oran wrote, any reader who took the trouble to look at Mead’s appendices would have been puzzled by her conclusions.

A table in Appendix V reveals that she interviewed a total of 30 post-pubescent girls. But only 12 of these (40%) had any “heterosexual experience,” which is not defined. (Mead 1928, 285) No males were interviewed, as one would expect of any social scientist investigating sexual mores.

There is no discussion as to how pregnancy is avoided. One would imagine this would be of great interest to an ethnologist, and Mead would have questioned her informants closely. The art of love can only be practiced where its biological consequences can be avoided.

Readers may also have asked themselves why it was so prestigious to marry a virgin if free love was widely accepted.

But for the few skeptical readers of Coming of Age, the elephant in the room was the moetotolo. Though she admits digital rape is “curious” and “abnormal,” readers learn that it is one of three forms of relationship between the unmarried that receive “formal recognition from the community,” the two other being “the clandestine encounter” and “the published elopement, Avaga.” (Mead 1928, 89)

Larry Nassar had a more effective modus operandi than the young Samoan men. As Mead delivered her revolutionary message in the guise of an anthropologist, so Nassar engaged in moetotolo (the verb and noun are the same) while playing the role of physician. He didn’t slip into his victims’ bedrooms at night; they were ushered into his examining room for physical therapy.

***

The lesson of multiculturalism, taught as well by Ruth Benedict’s enormously influential Patterns of Culture, is that every culture has admirable beliefs and practices. It’s a mark of sophistication to collect non-Western artifacts and enjoy non-Western cuisine, but we can go further and adopt some of the practices of those societies when the natives appear to be happier than us, as they often do.

Anthropologists of the Mead-Benedict school were concerned exclusively with cultures, not technologies. They didn’t ask themselves why some cultures create institutions that produce unimagined wealth, comfort, security, longevity, leisure time, etc., and have made it possible for 2% of the population to produce food for the rest, who can do more entertaining work with their iMacs. Perhaps the behavior they find so neurotic is responsible.

Cultural determinists never ask why different peoples should have radically different cultures. Diversity is something to be celebrated, not accounted for.

Their limited curiosity aside, Mead and Benedict misrepresented the cultures we were supposed to emulate. (For Benedict, the “Apollonian” Pueblo Zunis played the role of the Samoans, welcoming homosexuality.) As Freeman and Napoleon Chagnon, Lawrence Keeley, Robert Edgerton, Steven Le Blanc and others have demonstrated at length, primitive societies are never harmonious and tranquil. Before the arrival of Christian missionaries, Samoans waged frequent wars and had a high level of interpersonal violence. Even in the late 1960s, forcible rape was twice as common in Samoa as in the U.S. According to Mead, however, only after “the first contact with white civilization” were there rapes, and even then these only “occurred occasionally.” (Mead 1928, 93) In a subsequent book she went further, claiming “the idea of force ful rape or of any sexual act to which both participants do not give themselves freely is completely foreign to the Samoan mind”—conveniently overlooking the moetotolo. (Mead 1975, 220)

ful rape or of any sexual act to which both participants do not give themselves freely is completely foreign to the Samoan mind”—conveniently overlooking the moetotolo. (Mead 1975, 220)

Even in the 1960s, when Freeman was conducting his research, he found “a preoccupation on the part of young men in general with the deflowering, by whatever means, of any sexually mature virgin, a success in this activity being deemed a personal triumph and a demonstration of masculinity.” (Freeman 1983, 245)

Dr. Nassar, accused of abusing over 250 young women, would have won Olympic gold.

***

Like Sovietologists, anthropologists have seen their field dry up. There are no more Ishis. There can be no more Sapirs. It should not be surprising that so many have embraced post-structuralism, and now deconstruct the history of their discipline. It should not be surprising that so many have become cheerleaders for multiculturalism. The savage fury with which the tribe of anthropologists attacked the iconoclasts Freeman and Chagnon astonished outsiders.

“The road of modern culture leads from humanitarianism via nationalism to bestiality,” wrote Franz Grillparzer. (Zweig 1965, viii) The Austrian dramatist died in 1872; he could not have imagined what awaited Europe at the end of the road in the 1940s. Today, things are different. The path from humanitarianism to bestiality leads through the cultural relativism of internationalism.

The sexual revolution has been won. Multiculturalists no longer extoll the supposed enlightened attitudes toward sex of non-Westerners. They are admired merely because they have been victimized by Europeans, replacing the workers exploited by the bourgeoisie. But whereas not so long ago multiculturalists simply ignored the rebarbative patriarchal practices of their heartthrobs, like the segregation of and denial of rights to women, the burqa and hijab, cousin marriages, honor killings, female genital mutilation, etc., they have now begun to defend some of these.

FGM, referred to as “circumcision” or, better, “surgery,” is now regarded as a harmless cultural inheritance under assault by insensitive Islamophobes. The bioethicists at the Hastings Institute have given the practice their seal of approval. Mead was sympathetic to the moetotolo, and, so long as he isn’t a white male, he, too, may eventually find even more outspoken supporters.

___________________________

Caton, Hiram (ed.). 1990. The Samoan Reader: Anthropologists Take Stock. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

Caton, Hiram. 2006. https://www.amazon.com/Confronting-Margaret-Mead-Legacy-Scholarship/dp/0877228868?ref=pf_vv_at_pdctrvw_dp

Freeman, Derek. 1983. Margaret Mead and Samoa: The Making and Unmaking of an Anthropological Myth. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Freeman, Derek. 1999. The Fateful Hoaxing of Margaret Mead: A Historical Analysis of Her Samoan Research. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Howard, Jane. 1984. Margaret Mead: A Life. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Lovejoy, Arthur and George Boas. 1935. Primitivism and Related Ideas in Antiquity. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Mead, Margaret. 1928. Coming of Age in Samoa: A Psychological Study of Primitive Youth for Western Civilization. New York: Morrow.

Mead, Margaret. 1975. Male and Female. New York: Quill.

Orans, Martin. 1996. Not Even Wrong: Margaret Mead, Derek Freeman, and the Samoans. Novato, CA: Chandler and Sharp.

______________________________

Jeff Lipkes is the author Rehearsals: The German Army in Belgium, 1914 and Politics, Religion, and Classical Political Economy in Britain, the co-translator of Henri Pirenne’s Belgium in the First World War, and the editor of a selection of the letters of Sir Edward Grey, Dear Kathryn Courageous. As Josh Michaels, he has written a novel, Outlaws, and edited and introduced a selection of the aphorisms of Mignon McLaughlin, Aperçus. He is completing a volume on the books read by American antisemites who read books. Many of his non-scholarly articles are available at American Thinker. For more information, see jefflipkes.com

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link