by Kenneth Francis (May 2020)

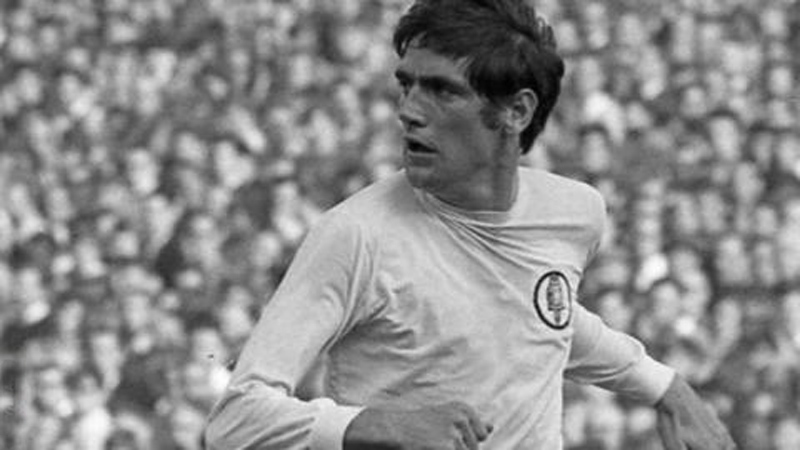

Norman Hunter, Getty Images

With the recent death of football legend Norman Hunter (1943-2020), any follower of UK soccer who remembers the glory days of the 1960s/’70s will never forget the great success of the Leeds United team he played for.

Under the management of Don Revie, Leeds were, in my opinion, the greatest soccer team in English football history. However, despite being as-hard-as-nails tough guys, they were unfairly accused of gratuitous ‘dirty play’ by many rivals who ignored similar behavior of their own team players.

At Elland Road during Revie’s reign (1961-74), Leeds won the league title in 1969 and 1974, the 1972 FA Cup and the Fairs Cup—the Uefa Cup’s predecessor—in 1968 and 1971, a run of success that began with the 1968 League Cup. They were also runners-up in the league five times and lost five cup finals.

As a young lad, I remember buying packets of football soccer player cards (similar to NFL Rookie Cards), which I would swap with friends if I bought a repeated pack with photos of the same stars. We would stick the cards on our bedroom wall in a horizonal line until we got a full team. These Leeds players, like most soccer players of yesteryear, always looked quite mature for their age, whereas the six-foot Norman Hunter looked somewhat youthful.

Hunter, who played 726 games for Leeds and scoring 21 goals, joined the team at aged 15. He also played for England and was a tough tackler playing at centre-back and defensive midfield. His rivals nicknamed him, ‘Bites Yer Legs Hunter’.

The nickname originated from a banner, held up by Leeds United fans at the 1972 FA Cup Final against Arsenal, which read ‘Norman bites yer legs’. And to an extent there was some truth in this, not literally of course, as he was a hardman of soccer but also a very skillful player and a likeable gentleman off the pitch.

One also has to remember these tough players in context. Before 1970, British footballers played on quagmire-condition pitches, often in torrential rain, with soggy footballs that weren’t waterproof. There was very little diving or feigning of injuries from these Leeds men of steel. And referees weren’t the great protectors that they are today.

When a player was fouled and fell to the ground, he usually sprang back up onto his feet and squared up to the man who crocked him. This often ended up in mass brawls where the other team members would get involved. In one such brawl in 1975, Hunter got into fisticuffs with Manchester City’s Francis Lee.

Lee was a fine player but rivals often accused him of feigning a foul by diving in the penalty area and winning a penalty kick, thus he was nicknamed ‘Lee Won Pen’. Referees’ chief Keith Hackett said Lee “had a reputation of falling down easily.” In the above game after the punch-up, both players were sent off the pitch and the incident was, in 2003, named by The Observer newspaper as sport’s most spectacular dismissal.

Many years later as both players retired, Hunter recalled meeting Lee on the stairwell in some building. He told an after-dinner gathering that they looked at each other and Lee jokingly said: “Come on, the board room’s empty, Norm; we’ll finish that fight and see who wins.” Both men smiled at each other and went about their business, with Norman saying afterwards that he regretted the pitch brawl. “There’s things you do that you look back and think you should’ve never done them . . . But that’s football,” he said.

Other brawls included the 1974 Charity Shield match between Leeds and Liverpool Utd. It was the first time the Charity Shield had been televised and the first time it had been played at Wembley. In the second-half of the game, a fist-fight between Liverpool’s Kevin Keegan and Leeds captain, Billy Bremner, occurred. The brawl led to them becoming the first British footballers sent off at the national stadium. Both men tore off their jerseys as they left the pitch, Bremner throwing his to the ground. The incident led to questions in the UK Parliament.

Aside from fouls: When I reflect back on those glory days of the Sixties and Seventies, what strikes me is the difference in style to the games of today. At the end of the 1970s especially, and the last World Cup of that decade in ’78, there seems to have been an evolution in style and substance on the field.

Take for example the ’78 World Cup won by Argentina. It certainly wasn’t the greatest of World Cups but it did feature a spectacular gem, by Scotland’s Archie Gemmill, that some believe was the greatest goal of all time: so great that a choreographer, Andy Howitt, created a dance to it back in 2001. I can’t imagine someone choreographing such majestic dribbling skills today, even if carried out by the great Cristiano Rinaldo.

But Gemmill’s great goal aside, and before today’s modern game of soccer, there was something poetic about the slower movements of the players of yesteryear, even if Hunter’s on-field tackling was a bit on the rough side. As a former Leeds fan, maybe I’m being a bit too nostalgic or subjective, but doesn’t contemporary football and its overpaid stars lack soul?

Today, some stars can earn £400,000-per-week.

Average wages for English soccer players in the top division ranged from approximately £50 in mid-1960s to £120/£140 in the mid-1970s. Besides Nottingham Forest’s Trevor Francis, one of the first big earners at the last year of the 1970s was England goalkeeper Peter Shilton, who was paid £1,200-a-week.

As for style: Over the past 25 years to date, premier league football looked to me like a chess machine on steroids, where every player functions to the best of his ability. In other words, they seem to be constantly striving for efficiency, both physically and proficiently, in order to become more, well, pitch-efficient, if you will.

But back to the Leeds of yesteryear who were no angles and were no stranger to fouling other players. Former excellent player Johnny Giles, who played for Leeds from 1963-’75, summed up his team’s approach to games perfectly: “When people talk about Leeds being dirty, they forget that was the culture back then. You had to look after yourself. There were so many players around who would now be suspended all season long. We just made sure nobody ever managed to bully us.”

Giles, who is Irish, left Leeds shortly after manager Brian Clough took over in 1974, with the latter calling a meeting with the team a few days into his new job. In his memoirs Giles, who had been passed over for Revie’s job, wrote: “I have seen it reported, in fact and fiction, that he [Clough] opened with the word ‘Gentlemen’ but that was not the case.”

According to Giles, Clough said to the players: “Right you f**king lot, as far as I’m concerned you can take all the medals you have won and throw them in that bin over there.” To Norman Hunter, Clough added: “Hunter, you’re a dirty bastard and everyone hates you. I know everyone likes to be loved, and you’d like to be loved too, wouldn’t you?” But Hunter replied: “Actually, I couldn’t give a f**k.” Unlike Clough, when Don Revie was manager his personal relationship with Hunter was so strong that other members of the squad would jokingly refer to him as “Norman’s dad”.

I don’t like people swearing, but I think the much-loved Norman was right to stand up to Clough, despite him being a man of great talent. Speaking on Irish Newstalk radio programme, Off the Ball, Giles said he regarded Hunter as a very good friend and an exceptional character who you could depend on with your life.

He added: “He was very genuine, very modest and would never talk about himself. He felt privileged to play football at the level he was at. I played with him for 12 years, and it is honestly like being in the army together. Especially in those days, you had to stick together. There is a bond from that that never dies.”

Hunter, who was married with two children, had underlying health problems in his retirement. He was admitted to hospital on April 10 where, according to the mainstream media, he tested positive for Covid-19. He died on April 17, aged 76.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

__________________________________

Kenneth Francis is a Contributing Editor at New English Review. For the past 20 years, he has worked as an editor in various publications, as well as a university lecturer in journalism. He also holds an MA in Theology and is the author of The Little Book of God, Mind, Cosmos and Truth (St Pauls Publishing) and, most recently, The Terror of Existence: From Ecclesiastes to Theatre of the Absurd (with Theodore Dalrymple).

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link