by Christopher DeGroot (June 2018)

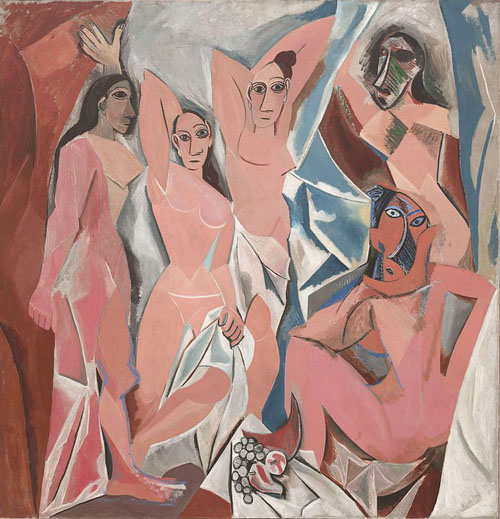

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, Pablo Picasso, 1907

In the wake of the #MeToo movement, many people are rightly concerned that a woman’s mere accusation is now widely taken to be tantamount to evidence of sexual harassment or of sexual assault. Last December, in a thoughtful essay in The American Interest, fittingly called “The Warlock Hunt,” Claire Berlinski captured this concern:

It now takes only one accusation to destroy a man’s life. Just one for him to be tried and sentenced in the court of public opinion, overnight costing him his livelihood and social respectability. We are on a frenzied extrajudicial warlock hunt that does not pause to parse the difference between rape and stupidity. The punishment for sexual harassment is so grave that clearly this crime—like any other serious crime—requires an unambiguous definition. We have nothing of the sort.

In recent weeks, one after another prominent voice, many of them political voices, have been silenced by sexual harassment charges. Not one of these cases has yet been adjudicated in a court of law. Leon Wieseltier, David Corn, Mark Halperin, Michael Oreskes, Al Franken, Ken Baker, Rick Najera, Andy Signore, Jeff Hoover, Matt Lauer, even Garrison Keillor—all have received the professional death sentence. Some of the charges sound deadly serious. But others—as reported anyway—make no sense. I can’t say whether the charges against these men are true; I wasn’t under the bed. But even if true, some have been accused of offenses that aren’t offensive, or offenses that are only mildly so—and do not warrant total professional and personal destruction.

Close students of human nature will not be surprised by this turn of events, for it is the way of men and women, in the face of a profound moral evil, to react in an extreme fashion, thereby producing new problems to deal with. For indeed our moral values, being essentially affective in their experiential character, lend themselves to such irrational conduct. Believing, as of course is only just, that women should not be sexually harassed or sexually assaulted, it is only too easy, passionate creates that we are, for us to overlook the fact, though so logical, that the accusation of a thing is not proof that it occurred.

What is more, sexual assault and sexual harassment are exceedingly difficult issues because in our culture as in all others there is a natural and powerful paternalism. Protecting women is a kind of instinctive biological imperative, and so it is that most people, albeit unwittingly, tend to side with women when it comes to accusations. That this would be so is reflected in other areas of life: women tend to receive lighter prison sentences than men, for example, and we have all heard stories about women getting out of speeding tickets where men are not so lucky.

Still more, feminism in the last few decades has become a kind of willful self-abasement or psychological masochism to which feminists must adhere. That is why they want us to conceive of ordinary men as sexual predators. After all, if men are not forever sexually assaulting women and keeping them back generally, then feminists will have nothing to oppose. They will be out of a job, and may have to turn to a serious field, in which a sophistical, horribly written book like Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble (1990) does not merit admiration. Talk about jobs is certainly warranted here. After all, from Harvard down to Teen Vogue, feminism has become an industry. It follows that even if feminism, by its very character, is unfair toward men, nevertheless there are many people, not all of them women, who will resist the principled conception of feminism—call it freedom dependent upon responsibility—that both Camille Paglia and Christina Hoff Summers, much the best of American feminists, have long called for. Let men be men and women be women, Paglia urges, yet the problem is that feminists have a vested interest in men being conceived of as monsters, and women as their victims.

It is owing to the terrible power of feminist influence that, as we see from the #MeToo movement, a mere accusation is now widely considered to be tantamount to evidence of sexual harassment or of sexual assault. In an essay for The American Spectator, I noted that “feminists are generally biased and poor thinkers. The reason is simple and clear: per their agenda, which they assume is always applicable, they do not consider contexts objectively. On the contrary, they perceive, and therefore reason and evaluate, in a priori terms.” Given this a priori agenda, this biased insistence on making victims of women, it is now quite difficult for allegations of sexual harassment and sexual assault to be handled fairly.

This difficulty, to be sure, is closely related to our rotten universities, where feminism is a sacred cow. Ideas and values, having become popular in the academy, eventually spread throughout the culture. Irresponsible feminist academics, therefore, exercise an immensely harmful influence. And they have been doing so for quite some time. Indeed, it took the backlash to #MeToo to shed light on what is by no means a new phenomenon: the reflexive bias toward men, so built into the culture that few even notice it, it being most people’s normal, as it were. We find a representative example of this type of irresponsible feminist academic in the writer Becca Rothfeld. Though a PhD candidate in Philosophy at Harvard, she does not appear to be a lover of Sophia. In an article in The Baffler in October 2014, Rothfeld writes of males writers of “alternative literature,” men who, in her judgment, are essentially pretend progressives. According to Rothfeld, “the alt-bro-man-child [i.e., male writer of “alternative literature’] is just a fratty wolf in your leftist grandmother’s clothing.” Furthermore, she says,

he’s not just a figment of the blogosphere’s nightmarish imagination. In recent weeks, he’s made another appearance, this time not in the The New Inquiry or The Awl but in horrible, vicious earnest. Two alt-bro fixtures of the alt-lit community, Tao Lin and Stephen-Tully Dierks, have been accused of sexual assault. Though this is not to say that all alt-bros are rapists, and though physical abuse is magnitudes worse than mere smugness and entitlement, the two behaviors are not unrelated: it is clear that the alt-bro-man-child’s practiced dismissal of female agency can have devastating material consequences.

From the beginning, feminism has largely been an affair of middle and upper-class women. Feminists in general seem quite unaware of how much they, indeed how much we all, owe to the unappreciated blue-collar men who keep the world running, to those manly men who build buildings, pave roads, haul freight, clean sewers, fix electrical wiring, among other thankless tasks, including, above all, defending the state itself. Behold the comfortable, plump First World feminists reposing on the backs of masculine labor as they cry “Down with the patriarchy!” Like spoiled children, feminists in our time are marked by a perpetual dissatisfaction, the result of their deep ingratitude and unrealistic expectations. So it is with Rothfeld. “Smugness and entitlement.” Here is a bourgeois woman’s revealingly ungenerous and ironically smug and entitled perception of a type of man who is “always expounding on how identity politics detract from the real issues,” having “witnessed too many of his intellectual peers succumb to caring about lesser things such as gender and postcolonialism.” It is as if a man owed Rothfeld a commitment to “identity politics,” and failing that, he’s a bad guy. In a review essay, published last June in The Chronicle of Higher Education, Rothfeld declares that “most women in the academy or the literary world have at one point or another been cast as headstrong girls who talk too much and too loudly, whose demands are voraciously great: too much, crazy, hysterical, shrill.” Well, yes, one thinks, your “demands” certainly are “too much,” Ms. Rothfeld. Nor does any healthy-minded man want to go with you to the new and improved, intersectional Vagina Monologues.

Given such an egotistical character, the main problem with The Baffler passage quoted above hardly seems surprising: namely that, in her contempt for the “two alt-bro fixtures,” Rothfeld is quite willing to imply that Lin and Dierks are guilty. They are not indeed “figments of the blogosphere’s nightmarish imagination,” but wolves “in your leftist grandmother’s clothing.” Why the facile presumption of guilt? Because, despite what she may say, in a certain sense Rothfeld undoubtedly wants the sexual assaults to have happened, for only this sort of thing suits the requisite victimhood agenda. Again, without that, what would have feminists have to do? Well, they might fix their attention on the horrible treatment of women in the Islamic world, something that, with their aversion to being politically incorrect, they have been rather unwilling to do.

Neither Lin nor Dierks, it should be said, was ever charged with sexual assault (not to imply it didn’t happen). In 2014, E.R. Kennedy, a “transman,” accused Lin of statutory rape, which, Kennedy alleged, occurred back in 2006, three years before Lin published “his” poetry collection in 2009. Hard to believe, isn’t it, that you’d have your rapist publish your poetry? According to Lin, he and Kennedy were in a long-term relationship and the sex was consensual. Notwithstanding “his gender identity,” Kennedy is really a woman, and these highly implausible circumstances suggest a distinctly female type of revenge.

In Dierks’ case, one sees, what Camille Paglia has often observed, that in many cases of alleged sexual assault, young women simply don’t know what they are doing, unaware of the symbolic meanings of their actions, and too passive, too immature to be in the sexual arena. One of Dierks’ two accusers is a woman named Sophia Katz. By her own account, she traveled to another country in order to spend a week exploring New York City and going to literary readings and doing drugs with a man whom she had never even meet and knew only through email exchanges.

He explained that there would be three other people staying in his apartment at the same time I would be there, and that I was “welcome to sleep in [his] bed if [I would] be comfortable with that haha.”

“I’m down,” he continued. But if I wasn’t, I “might wanna find a different place.”

I explained that I didn’t mind sleeping on the floor, and that I would bring my sleeping bag. I hoped this would help him understand that I was in no way romantically interested in him, but he ignored my suggestion and moved onto explaining that his roommates were fine with my staying at the apartment . . . In the back of my mind I felt mildly concerned that he believed my main focus in New York would be pursuing a romantic or sexual relationship with him, but I put aside my concerns and assumed that this wouldn’t be the case. Worst case scenario, I would have to verbally explain my wishes and slightly damage his ego.

Dierks’ sexual intent is evident here, and when he told Katz that if she wasn’t “down” then she “might wanna find a different place,” she should have understood that her talk about sleeping on the floor would not change what the horny young man had in mind. Putting aside her concerns was an unwise decision. So too, not verbally explaining her wishes ahead of time.

Here we perceive a familiar problem between the sexes. Women are generally more intuitive and subtler than men; preternaturally sensitive to others, the maternal sex doesn’t need things to be straightforward, so they tend to assume that men will just “get” their rather covert communication. This difference might be altogether funny, were it not so often tragic.

“Listen,” I said, sitting up and leaning away from him. “I really didn’t come to New York to, like, have a relationship with you or sleep with you. That’s not why I’m here.”

His expression immediately changed.

“Okay. I don’t really understand but okay,” he said.

Indeed, Dierks does not understand. Many men would not. And in our feminized era, many women seem not to understand that, like the males of other animals, it is in the nature of men to pursue women and persist in their attempts to have sex. Being inherently irrational, sex can easily make for dangerous situations; and hence it has historically been determined by grave sanctions and customs, none of which has taken the form of a woman travelling to a foreign country in order to stay with an unknown man.

“I had no interest,” says Katz, “in making out with him or having sex with him.” And yet, she did stay at Dierks’ apartment, not long ago a universal sign of sexual interest, and perhaps still usually interpreted as such by men, although more and more this seems lost on women, since it is the function of feminist social conditioning to excuse women from any responsibility whatever, lest one should “blame the victim.”

Katz describes part of one of their sexual encounters as follows: “I felt tears welling up in my eyes and tried to dissolve them. I didn’t want to do it later. I didn’t want to do it ever. I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I wanted to leave, but I was trapped with him in his tiny, dimly lit room.” While it is not my aim to suggest that Dierks is innocent of sexually assault or morally blameless—I am rather trying to clarify what seems to have been a messy, ambiguous situation from the beginning—it needs to be said that there is nothing in Katz’ account, sad and sympathetic though it is, which supports the claim that she was truly “trapped” in Dierks’ room. She does not say, for instance, that Dierks restrained her. She surely could have left—but didn’t. Of course, Katz was alone in a room with a strange man in a foreign country. “Trapped” may be her way of saying that she didn’t know where to go. But having planned to stay in New York City for a week, she presumably had made plans to return, and the sensible thing would have been to go home early; that is, there and then, before a sexual assault or anyway a regrettable experience could take place.

Rothfeld writes of “the alt-bro-man-child’s practiced dismissal of female agency,” but where was Katz’ own “female agency”? We see it in this sentence: “I didn’t know what I wanted to do.” And that anxious puzzlement is repeated throughout Katz’ story. Having ignored her initial misgivings and, despite her ongoing discomfort, remaining in the apartment even though she could have left, all while allowing Dierks to treat her to free meals, alcohol and drugs, Katz appears to be just the sort of woman whom Paglia has often criticized for failing to be prudent and assertive, as women must be if they are to be equal. Though he posted a public apology to Katz on Facebook, Dierks said in it that he didn’t realize that, to her, the sex was not consensual. Maybe that was a lie. Maybe it reflects an honest misunderstanding—that, in his own words, Dierks “gravely misread the situation.” It seems plain, at any rate, that his dealings with Katz were confused from the beginning.

At the end of her account Katz says:

I would like to think I wouldn’t have let him claim my body as his own. But the reality is that I did. The reality is that this happened. The reality is I’m not the first person he has done this to, and if I say nothing, I have a feeling I won’t be the last.

While Katz didn’t want to be intimate with Dierks, she is well aware that she “let” it happen. Is it any wonder that Dierks believed the sex was consensual?

Notwithstanding academia’s “affirmative consent,” sex is not a rational, orderly affair

Direks’ second accuser is a woman who goes by the name of Tiffany (whether that is her real name is unclear). One night she got drunk and went back to Dierks’ apartment. She claims that she “protested” his advances, but like Katz, she remained with Dierks. In her own words:

Stephen kicked off his shoes, lowered himself onto his bed and crawled over to me. He began caressing my arm and pressed his mouth against mine with feverish urgency. I protested, but it immediately became clear that my attempts were futile. I lay still and stared at the ceiling as he groped and fondled me. Eventually, as Sophia did in her story, I began to do things that I thought would make him finish faster. He used my body off and on all night until he fell asleep. I willed the sun to rise faster. After a few hours that felt more like an eternity, he told me that he had to go to work. I nodded, and he kissed me one more time before getting up to go shower. As soon as I heard the water running I gathered all my things as fast as I could and left his apartment.

. . . I didn’t know how to process what had happened, so I coped by lying to myself and to everyone else. When my friends expressed their concern I told them that everything was fine, that we hooked up, that it was whatever. I never fully believed that but I managed to convince myself and everyone else that I did. I began to avoid Stephen both online and in person, but after some time I convinced myself that what had happened was an isolated incident of misunderstanding. Months passed and it blew over. I rebuilt a friendship with Stephen on the pretense that everything was okay. Out of sight, out of mind.

In the course of the 12 hours since I found out about the existence of Sophia’s piece my life feels like it’s been turned on its head. Instead of worrying about the mountains of homework my professors have been steadily piling on week after week, or where my friends and I will bicker over going out to eat tonight, I’m grappling with crushing fear and anxiety. Stephen took so much from me and I will be damned if I’m complicit in letting him take anything from anyone else.

If you read the whole of Tiffany’s account, you will probably notice the usual unwitting confusion of a young woman who just doesn’t know what she’s doing, as it were. Although it was surely a bad idea for Tiffany to get drunk and go back to Dierks’ apartment, it would still be wrong, of course, for him to sexually assault her. But is it clear that that is what happened? Perhaps, indeed, Tiffany’s “protests” were “futile.” Perhaps, for example, Dierks overpowered her. To be sure, though, we are not told what made those protests futile, according to Tiffany. And anyway, a horny young man, with a brain affected by alcohol, is certainly no mind reader.

Whatever may have happened, Tiffany later thought it was “an isolated incident of misunderstanding.” But then she learns of Katz’ story, and suddenly has a very different interpretation. Now this is rather like the morning after a drunken hook up at many a university: it is not until she has been in touch with another woman that a woman comes to think she has been raped, and in many cases those women are by no means disinterested. As I observed a little while back in one of my columns in Taki’s Magazine, women tend to be highly susceptible to the beliefs (read: feelings) of other women. On the whole, women are less independent-minded than men and higher in conformity. Certainly, we have all seen this in everyday life. When, for instance, a woman has to make a decision, more than a man, she is likely to consult another person, typically a fellow woman: her mother, or sister, or girlfriend, or whoever. Nor does it to take much for women to significantly influence other women, for perception and memory themselves to be altered thereby. As the psychologist Robert Bartholomew has noted, throughout history mass hysteria has been almost entirely a female phenomenon.

As far as I can tell, Dierk has not responded to Tiffany.

Anyway, no matter what happened, these three cases are certainly too different and too complicated for Rothfeld to be justified in her presumption of guilt across the board. We can also see, in the Dierk example, the prudence of the old custom of not going home with a man, or going to a man’s home, unless you intend to sleep with him. Though she is liberal-minded indeed, Paglia, with her usual good sense, endorses such traditional prudence, which, of course, was much less needed when sex out of wedlock was socially unacceptable. When it was reported that the Pences don’t meet alone with the opposite sex, feminists were predictably outraged. Yet ironically, they have much to learn from that conservative couple.

Memory, thanks to human egoism, is notoriously selective and unreliable. While one would never know it from reading Rothfeld, there is no dearth of women who are willing to exploit people’s deep paternalism in order to take revenge on men for an unhappy sexual encounter or for some other reason (such as the desire for money or attention). In fact, it is well-documented that this happens in abundance. From the universities to the workplace to Hollywood, a great many men have had their lives ruined by female lying and manipulation. “I can’t tell you how many times,” says attorney Justin Dillon, “I’ve seen this in my Title IX—accusers embellishing details and ultimately convincing themselves of things that did not happen.” By assuming that Tao Lin and Stephen-Tully Dierks are guilty, Rothfeld is a representative feminist hypocrite: she purports to stand for fairness, while in truth her aim is to propagate a sense of victimization, even if that should entail smearing the reputations of potentially innocent men. Now this is a perfect example of what often happens when one is committed to an a priori perspective. Even if your intention is good (as Rothfeld’s probably was not), evil may still result.

As long as it remains biased by definition, feminism is sure continue to be a frequent source of injustice in allegations of sexual harassment and of sexual assault—matters which by their very nature call for the most scrupulous nuance and objectivity. We ought, then, to follow the lead of Paglia and Hoff Sommers and call public attention to the actual function of feminism today, it having become a hypocritically unjust doctrine.

_______________________

Christopher DeGroot—essayist, poet, aphorist, and satirist—is a writer from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His writing appears regularly in New English Review, where he is a contributing editor, and occasionally in The Iconoclast, its daily blog. He is a columnist at Taki’s Magazine and his work has appeared in The American Spectator, The Imaginative Conservative, The Daily Caller, American Thinker, The Unz Review, Ygdrasil, A Journal of the Poetic Arts, and elsewhere. You can follow him at @CEGrotius.

More by Christopher DeGroot

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link