Part I of V – Read available Parts here

by Janet Charlesworth (September 2024)

Prologue

She recovered consciousness, and felt profound relief at the realization that he had gone.

She was lying on the floor.

There was sunlight streaming through the open windows. It bathed her in its warmth and brightness, and for a moment, she swam in memories of feeling good in the sun, feeling alive and well, comforted, secure, energetic, optimistic, hopeful, and strong.

Then she began to feel the pain. Her right eye was throbbing, swelling, and her mouth and chin. She tried to move her jaw, but stopped. Then she felt the sharper pains in her side and stomach, and then the aching in her back and buttocks.

A cloud must have crossed the sun for the light and the warmth disappeared.

She started to feel helpless and angry, and the tears welled with sharp salty bitterness and slid down her face. Her nose was running. Where was her handkerchief? Surely she didn’t have to use her sleeve. She couldn’t move her arms. Then her body convulsed as from its depths came its first expressions of its agony and ignomy. The great wracking sobs started to take over, but she stopped them. They caused more pain, and she stopped them.

She looked along the floor from where her head still lay, and saw her children playing still behind the chaise longue. Her daughters were peering at her from under it. Their expression was simply one of curiosity. Her son was sitting with his back toward her, apparently focused on a toy he had.

She tried to move, carefully testing to see how far she could extend her limbs. She noticed there was blood on her leg. She managed to sit up, using her right elbow and, propped against the wall, she waited for her breathing to steady and make its way further into her lungs.

Her right hand was swollen and bruised and wouldn’t function.

Using her elbows and back to help her, she tried to inch herself up the wall to a standing position. She couldn’t. She settled back into a sitting position on the floor, back against the wall, back really against the wall now, she thought. She expected she would have to wait for the maid to be along.

It was really bad this time. The worst it had been. She must have lost consciousness. Oh yes, now she remembered. He said she had moved one of his books. He had left one of his books on the floor, and she had moved it, put it on the book shelf, out of the way of the children. He must have thought she had been reading it. He did not want her to read his books. She had realized that some time ago, and was always careful to ensure he would not find out by leaving the books exactly as she had found them, and by never talking to anyone else about what she had read. But this time, it was the children she had been thinking of protecting from his wrath. If they had damaged the book, there would have been hell to pay. He had returned unexpectedly, and found his book had been moved, and there had been hell to pay.

It was 1840, she was wife to the Squire, owner of all the land thereabouts.

The Squire had turned out to not be the person he had appeared to be in their highly supervised meetings prior to the wedding. She had thought him intelligent, well read, educated, secure in himself, just and balanced, and someone she would be able to respect and learn from. She expected he would encourage her to learn, support her in her thirst for knowledge, that he would take pride in having an intelligent and well-read wife. But this had not been the case. He seemed to feel instead that her intelligence, and interest in his books, were a threat to him and his authority, and he had been furious and forbidding.

The beatings started after their first child was born. She had talked to the doctor who ministered to her wounds from the beatings. He had refused to help her. She had talked to the minister at the church about the state of her marriage, hoping for help and support there. He had advised that she must have committed some grievous sin to have God permit such things in her life. He had exhorted her personally, and through Sunday sermons, and his interpretations of Scripture, and his support of the general attitudes and prejudices of the day, to repent, to take better care of her husband, to be more submissive, to stop reading books, or doing anything that angered her husband, to dress up more, to wear some rouge perhaps, to be available for sex, at any time, in any way.

But she did not feel she was responsible for her husband’s cruelty. She managed her home well. Her staff respected her. She was a good-looking woman, and was careful of her appearance. She had given the Squire healthy children. They were well cared for, well educated, and well behaved.

She wondered who this god was that her husband, her doctor, and her minister talked of—it wasn’t the God she felt in her inner being, and who she submitted to, and answered to. It wasn’t the God she had come to know in her years of Bible reading, and prayer.

She had been raised to accept male domination, and her role in life as wife and mother. The only sin she could think of was a secret one as far as she knew, and that was that she questioned the assumption that she was inferior, and that every male on the planet was her superior. She had intelligence and courage, and though she knew those qualities were not welcomed by her husband, if they were her sins, she had been born with them, and surely one could argue that it was God that had given them to her.

Her life with the Squire had been hard. He was a cruel man. He sought sympathy and justification for his behavior in claiming he was still heartbroken at the death of his first wife, saying that she, his second wife, was an affront to his memories of better times, and that he should never have married again. He was abusive, promiscuous with the female staff, irresponsible and selfish. And now he wanted her to go, to leave him, the children, and her home. She was simply to be replaced. He had someone else, someone who did not challenge his sense of himself as superior, someone who would never want to read any of his books, someone who spent her days attending to her appearance so as to please him.

Though she was his wife, and the mother of his children, she had no rights under the law. He had threatened to put her away in a lunatic asylum if she didn’t “see sense” as he put it. She knew he had the power to do that, and the will. The offer of the home at Cubdale was preferable to that.

She knew she was going to have to leave, and that she was going to have to leave her children.

One

Once upon a time, there was a land called England. It was a green and pleasant land by reputation, and in reality; a land filled with fields, flowers, trees, cattle grazing, horses, sheep and deer, foxes and pigs, thatched cottages with flower filled gardens nestled in villages in sheltered valleys with streams running through them, and a church up on the hill. There were cricket grounds and village schools where little girls still wore pretty frocks and white ankle socks and the boys wore knee length trousers, white shirts and ties. You could see them in the playground at morning, lunch and afternoon breaks, playing games like rounders, hop-scotch, tag, cricket and netball, and laughing and shouting in delight at being out in the fresh air and sunshine surrounded by the open country and the birds singing, and not a cellphone in sight.

The area she visited most was a designated National Park. And because of that, time had stood still there, and that once upon a time England still existed in that area. Cell phones didn’t work too well; something to do with a lack of towers, and the dips and depths of the rolling hills and valleys cutting off the connections to what towers there were. She enjoyed the feeling of being just that bit further cut off from any intrusion into her real life, her inner life. She hadn’t tried to connect to the Internet, but hoped that it too had been unable to establish a firm grip.

She knew she was indulging in a kind of romantic sentimentality in returning to the area, indulging in an idealized vision of home. For her, home had been far from the idyllic surroundings she found in the National Park. The home in the Park was the child’s fantasy of the kind of home that Dickens portrayed so well as the rescuing element, the safe harbour that his neglected and abused children from the inner cities eventually found; fresh air and sunlight, safety, security, containment and protection in the arms and hearts of adults with expansive means, loving kindness, and good and upright character—something like a child’s view of God.

Once upon a time was a good way to describe where she was, though the cottages now had running hot and cold water, bathrooms and attendant sewage arrangements.

When she had been a child, there had been a distant relation who lived in a cottage in Cubdale. Alas, that cottage was not included in the National Park designation and so it, and its country environment, had been gradually overtaken by a growing nearby once village in the process of becoming a town.

When she had last been there, the cottage had still retained a country atmosphere. There was no running hot or cold water, and no bathroom, and there were chickens under the kitchen table. Cold water came from a pump in the garden. Hot water came from heating the cold water on the fire, if there was one. The toilet had been a wooden hut down the garden which one entered with trepidation and a determination to not be intimidated by spiders, mice or rats as one perched, with exposed buttocks, on a piece of wood with a round hole in it, suspended over a dark and deep void into which one’s bodily products fell and were silently absorbed. The hut was moved from time to time.

That cottage had since been sold, demolished, and replaced with someone else’s dream of home, along with all the attendant sewage requirements.

She was lying on her back in the long grass on the hillside, just beyond the local church. It was a beautiful day. The sun was warm, the breeze was light. The skylarks were soaring and singing. The tall grass waved in the breeze. There was the scent of the hawthorn trees, and buttercups and tall daisies wafted around her head. The odd butterfly fluttered by. Small white clouds scudded across the deep blue of the sky.

She felt blissfully happy.

She closed her eyes, and let her thoughts wander.

She could remember lying in the grass like this when she had been a child.

She had enjoyed it then.

She started thinking about her childhood.

Her childhood was shrouded in mystery. She had little recollection of any of it. An analyst, in later years, summed up her childhood as “difficult,” though Jess was uncertain how she had arrived at that conclusion in view of the almost complete lack of recall on her part. There were photographs of course. Not many, but there were some. And she would look at the child in the pictures, and have no sense of connection to her whatsoever. She could see how, over the years, that child’s expression in the photographs went from a beaming confidence as a baby, to a frowned withdrawal as a girl of 5 or 6, to a forced grimace as a teenager.

Her older brother was never smiling in any of the few pictures there were of him. His expression was always clouded. Though his eyes might meet the photographer, they were looking up out of a face turned down, or sideways out of a face turned away, and the expression in the eyes was one of submission, hurt, suspicion and distrust.

She had found it surprising to see that. Her older brother had always been the favourite. She would have expected him to be beaming, happy, full of vim and vigor. But it was not the case. He was dead now—murdered in a home invasion in a strange land on a Christmas Day.

She knew that her parents had been very unhappy. There had always been friction and tension in the household. For Jess, it seemed that her father always had a scowl on his face, and was always growling and complaining about his ungrateful family. She could remember lying awake in her bed in the attic room at night, her older brother always had the decent other bedroom, listening intently for the sound of her parents’ raised voices, feeling their anger and unhappiness as threats of destruction to what was left to her of a frail sense of an ever receding margin of security.

Her father resented the expectation of his culture that he should provide for his family’s needs. He raged against his wife, and ignored his children. He seethed with bitterness, but did not have the courage to strike out and find his own path. Her mother too had not had the courage to break out, and find her own path.

It seemed to Jess now, from the advantage of long years of independence, that the collective imperative that men look after their families had always been, for many women, of uncertain reliability. The women who did try to break out and find a new way, who pushed for an opportunity to get an education, and a way in the world that would enable them to support themselves, the wave-breakers, all too often endured discrimination, and systemically approved barriers and handicaps, and found themselves short on opportunities and, without the protection of a man, bereft of status or support in a still male dominated culture and economy. It took a great deal of courage to do that, and Jess did not condemn her mother for shrinking from the task.

Men dominating and controlling women had been the norm in the England of her childhood. For her, it had been soul destroying. Though church attendance had been on the decline for many years, and fear of the patriarchal god was becoming rare, the church continued to teach female submission to male dominance as a spiritual law, a commandment from its god, a god that was totally male, of course, and the culture it had once dominated had obligingly gone along.

As for her soul, according to the patriarchal church, she didn’t have one.

It seemed to her that it was the arrival of the birth control pill in the 60s which had begun the change of status for women in her culture. The 60s had seen the beginnings of revolution generally in all areas. Initially, the birth control pill was only available to married women, and on a doctor’s prescription. Eventually, the pill did become more generally available. For those women who grew in economic strength and independence, it also became their choice as to whether or not they were going to involve the male in the upbringing of their child and its support, should they choose to have a child.

The birth control pill and the feminist movement had started the process of putting the means of survival in an economy that was increasingly based in technology, not muscle and brawn, into the hands of women.

Likely it was time for another revolution. Move on, or regress and die, seemed to be the law of being. She had felt that, had felt driven to understand, to move on, to keep moving, keep reading, keep thinking, keep musing, keep imagining. She was quite sure that if she had not done so, she would have died by now, like her brother. Her path though had been a lonely one. She had found that most people preferred to keep their focus on how well they were doing in adapting to their culture and its measurement of success. They wanted to feel that they belonged, were contained, were accepted, were loved. They wanted to ignore anything that might suggest to them otherwise. And they would pursue all the trappings and camouflage that the culture suggested they needed, and sold to them, as evidence of their success at containment, belonging and status. They looked at her askance when she suggested that they were just keeping busy so as to not look at how empty it all was.

Of course, there is love. And, of course, there is what passes for love. It seemed to her that everyone she knew was settling for what passed for love. She didn’t blame them. The agape variety was pretty hard to find. And why not keep trying.

Belief systems, social structures, social engineering, sociobiology, reproduction, births, deaths, economies, climates, climate change, immigration, countries of origin, air travel, sea travel, space travel, electricity and oil, and cars, and bikes, and just plain walking, and dogs, and cats, and fish in the sea, and birds in the air, and trees, plants, flowers, insects, reptiles and other animals—the whole fantastic cosmogloriphic chaos of life. And some people she knew felt they had it all put together in a semi-detached house in suburbia.

Well, she thought, its as well to know one’s limits. It’s all about that really, she thought, a wise person knows their limits. She understood about the felt need for a container, something with rigid sides and no leaks or breaks, ruptures or divides, for it contained that very fragile vessel called the ego. And we have to support our ego, she mused; it observes the chaos of life, and if it gives way, well, that chaos will just sweep in and take over and that ego will disappear, lose its function, die before its time, and what would be the use of that.

It’s all very well, she thought, breaking out of the culture’s containers, but where does that get one after all? Just lonely, outside the camp. Still, once the outside is seen, it’s impossible to crawl back inside. She chuckled at the thought that she was in fact inside a container of her own. Her walls were there just the same. Her walls were the outside of the walls that other people saw from the inside. Same walls though. Without those walls, where would she be. In a way, she was just as trapped by the containers as everyone else. Somehow, she found the thought cheering. There was a connection after all. And, getting up from her spot in the grass, and with a bounce in her stride, she made her way back to her hotel with thoughts of a good red wine and a steak for supper.

Two

Jess had found a remarkably decent Hotel for her base. The place had been recently renovated and had some excellent rooms for guests, all with private bathrooms and comfortable furniture. She had been very pleasantly surprised at the find. Her memories of accommodation in England were not pleasant. In the past, she had paid the earth for tiny, dingy rooms, hardly big enough to accommodate a bed, and its bugs, let alone a chair, and certainly not a comfortable chair, and never an en-suite bathroom. The bathroom was usually down the hall, grubby, an obvious renovation of what had once been a small back room, or a cupboard, and shared with all the other residents on the same floor.

The lucky find of her base had elevated her spirits to the point that she was actually feeling more open to indulging an expectation that the trip may go well.

Her room had a deep casement window, with an upholstered window cushion covered in a comforting chintzy kind of fabric with soothing darkish colours of principally muddy beige and maroons depicting birds, trees and maidens in petticoats. It was the perfect spot from which to survey the surrounding gentle countryside. The higher slopes with their craggy tops were still covered in bilberry bushes and bracken, and there were still walls surrounding clumps of trees. She had often wondered why walls were built around clumps of trees. Some wag had once told her it was to prevent them from wandering off. The fields were the deep vibrant green that she had only ever seen in England, and also, only in England, disappeared into a seemingly ever-present misty veil that prevented too far a view, leaving one with the impression that the landscape continued on forever.

It was deeply reassuring to her to find that nothing had apparently changed in the Valley and surrounding countryside. A previous government had zoned the entire area as a conservation site and a National Park. As a consequence, one could buy a property and do anything one liked inside it, but the outside had to remain the same. New development was not allowed. For people like her, it was perfect. She could come back to her old haunts, and find them preserved as she remembered them. Comforting to look at, reassuring in their sameness, speaking to her need for a sense of security and belonging, a need borne of many years of traveling around the world and living in places that were not home; beautiful, interesting, stimulating, yes, all those things, but not home. And her soul yearned for that sense of home, a sense of belonging, a place where she had a right to be. However, she had realized before too long that she was looking at a memorial to a bygone time. A kind of museum, or petrification of olde England. An illusion. She was beginning to realise that what she had always held dear in her heart as home was an experience, and not a place, and something she always had within her.

The local villager who worked on the farm, lived in a cottage in the village, raised his family there and met his neighbours in the local pub was a rarity now. The price of property was outrageously high, and beyond the reach of most ordinary country folk. Those that stayed on were either lucky enough to have bought their property when it was affordable, or they were renting, and likely getting help from the local Council to pay that rent. The farmers employed few if any workers year-round. Most of the work involved in planting crops, harvesting, haymaking, trimming hedges and so on was contracted out. The contractor arrived with the workers and the necessary machinery, and left when the job was finished. It was no longer necessary for the farmer to invest capital in heavy machinery, or to be involved in the obligations of employing workers year-round. The village population now was mostly made up of rich professional folk who could afford a second home away from the city for use as a getaway from their hectic lives. And there were always tourists in the area, which pleased the owners of pubs and restaurants, and the few locals who made crafts or had other retail outlets.

The Valley had become a tourist attraction, a kind of historical monument. It had become artificial. Again, she realized that the home she was attached to was in her own soul. It was like those tales of the Holy Grail, or the Yellow Brick Road, or The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. It was an inner felt sense of a need to return to her own roots, in herself. She had projected those roots onto her country of origin, England. And, she was beginning to realise, England could no longer sustain those projections.

Nevertheless, Jess found it a great comfort to be back. The sound of the birds singing, always birds singing, and such a variety of birds, filled her soul with a deep contentment and peace. She felt grounded, and closer to the inner experience of the concept of home.

Three

Jackson had decided to make a trip to Europe and England a few months after his wife’s relatively early death from cancer. He needed a break from the claustrophobic, constant, and well-meant attentions of family and friends, all of whom expected that he would be feeling grief, sadness, loneliness, and dislocation. He hadn’t had the heart to disillusion them and tell them that he wasn’t feeling any of those things. He had tried to gently convey to them that his state was nowhere near as severe as they appeared to imagine, without injuring their expectations of him, and their own feelings of loss, but to no avail. His wife had secured her following. For him to be open and honest with his own feelings of relief and release would have shaken too many trees, upset too many impressions.

He was well-aware that some in their circle of friends were only holding their own marriages together out of a mistaken belief that he and his wife had successfully shown that it was possible to resolve difficulties and achieve a harmonious relationship, and subsequently enjoy the gratifying rewards of a loving extended family. In a sense, this was true but, he was sure, they had no idea of the true dynamics and sacrifices underlying the appearances. He had four sons. None of his sons, nor his circle of friends, had known about the sacrifices he had made in the creation of the illusion of his happy marriage; sacrifices made because it had been easier to do that than to not do that. He had such a vast interior world, access to which was barred to outsiders, which included his wife, and from which he had found it easier to give his wife the comparatively little she seemed to need in order to create for herself a life that satisfied her, and to then leave him alone. In that adjustment and compromise, he and his wife had become, he knew, in the eyes of others, the perfect couple. But it had been a negotiated balance, and a relationship of compromise between strangers trapped in a cultural paradigm. Any romantic illusions that others might attach to the public face of that negotiated balance and compromise was, he felt, something that those who projected such illusions had to come to understand as illusions in their own good time, and in the course of their own lives and development.

Europe was his preferred area. He had been many times before, but always with his wife. His wife had a different pace. Different needs. Her objectives and resultant demands of what constituted a successful trip to Europe were all driven by her primary agenda of how it would all look when she got back to Canada, and what she would need to give all those coffee mornings and evening gatherings at their substantial home. She would show slides and videos and give informative talks on the art, architecture, culture and current political and economic state of the countries they visited, generally making an impression on their circle of friends of intellect, knowledge, maturity and wisdom. In his usual diffident way, he had accommodated himself to her agenda, finding ways to satisfy his own needs while swimming in attendance to her’s.

For a time after his wife’s death, he had wanted to stay in his home, and get accustomed to the feeling of her not being there. There was practical stuff to deal with. Where should he buy groceries? Did they pay their bills on the Internet, or by cheque? Who did the garden? When did the housekeeper come and how much was she paid? Had his wife tended the flowerbeds and who mowed the lawn? He had found out a great deal about the running of the household that he had always taken for granted. His wife had taken care of everything. That had been her job. His job had been to provide the money to keep the whole thing moving. She had also been the one dealing with family, making the arrangements, oiling the wheels. Now she was gone, he was faced with forming front line balances in his relationships not only with his family, but also with his friends.

He had dreaded their sympathy.

The adjustment to her death had not taken long. Her death had been expected, she had suffered a great deal, and when the end had finally come, it had been a relief to all of them. He felt released. He had no regrets. He had always fulfilled his obligations toward her. They had both come from families with a strong attachment to the church, and had a great deal in common. He hadn’t realized it at the time, but he had come to see that she was very much like his sister in appearance, even to the way she dressed. He had felt comfortable with her. They had married, and she had been a loyal and supportive partner, notwithstanding her frustrations with the role of wife and mother, a role she felt her faith called for her to adopt to the exclusion of any thoughts of a career of her own. Her frustrations had led to some discord in their relationship, and perhaps to his openness to Jess, but, for the most part, he had been able to escape into his work, and his wife had found other outlets for her animosity.

Over the years, the nature of his work had taught him an amused and resigned acceptance of life. Passions that had seemed at one time to be of life or death significance faded and died over time. Jess used to say that passions are of the gods, and humanity is of the earth, and needs bread and water, if not wine. The culture has its requirements, he had a position to keep, and there were financial necessities to deal with. His response to most crises was that they too would pass.

He had traveled to England in order to arrive in what passed for the summer in that part of the world. After a few days in the capital, and finding it far too busy, dirty, and inordinately expensive for less than appetizing food and accommodation, he had rented a decent car, a rather nice looking dark blue BMW, and made his way up the country to the less populated areas in the north, and to an extensive Valley and surrounding Moors area which was designated as one of the country’s National Parks.

Once he got to the National Park area, he had found the scenery restricted and compromised, but gentle and strangely reassuring if he was careful to choose strategic points to view it from. Where he came from, the countryside was not readily accessible, and was dangerous for those who ventured into it ill equipped or ignorant of its capacity to destroy. The spectacular scenery in his country could be viewed to a limited extent from the few roads that wound their way through it, but, in order to access that country and really see and experience its vastness and beauty, one had to fly in by helicopter with experienced people and, if one intended to stay more than a few hours, with enough kit that would be regarded in England, he was sure, sufficient to conquer anew the North Pole. The National Park seemed small to him; and the view was always limited by a kind of misty veil that perpetually hung over the landscape. Once beyond the strategically placed viewpoints, one’s view of the countryside was edged in by glimpses of villages, towns, cities, smoke, people, cars, motorways, houses, lots of houses, rows and rows of identical houses, rats in cages, stress. The strategic viewpoints looked out over pockets of controlled serenity, carefully guarded in the midst of an incredibly over crowded very small island. The lungs of the country, he had heard the Parks once described. Very accessible lungs, but also very limited lungs in constant danger of being completely exhausted by the ever expanding population moving in around them, a population that was now of a multi-cultural mix, a mix that brought a sense of unease and alienation.

He had found a decent room at a pub called the Red Lion, and booked in for a week.

The Pub had a restaurant noted in the Good Food Guide for England. The chef knew his stuff, but Jackson felt it was expensive for what was served, and the menu was limited. England was like that generally he had found, expensive and limited. As he explored the Park area, he had often found himself at other locations when it was time for his evening meal, and had taken to sacrificing his preferred experience of a civilized full and adequate dinner in congenial surroundings, where white tablecloths were to be found, for a snack in a Pub which always came with what the English called “chips,” and always cost a great deal more than he felt the food warranted.

He had spent the morning in the Highgate area of the Park, but the pangs of hunger for his lunch, the thought of exposure to another pub and its “chips,” and a sudden felt need for a quiet afternoon with a good book, turned his attention back to his room at the Red Lion, and he decided to make his way back there. He would return to Highgate and explore the area further the next day.

On his way back, he wondered if the landlord of the Red Lion, Symes, would be about. He hoped not. Symes seemed to have taken a liking to him, or an interest in him at any rate, and would generally endeavor to engage him in conversation whenever he was around. He had heard that Symes had banned people from his pub for being boring. Symes certainly gave the impression of someone who was full of self-confidence; his usual approach to his customers was a patronizing mockery, which some seemed to think was evidence of his intelligence. The regular clientele in his Bar resembled a fan club. Jackson assessed Symes as a defiant anti-establishment type of snob with a considerable chip on his shoulder. Symes ensured that one knew he had spent some years at university studying Sociology a couple of decades prior, and that on completion of his degree he felt he had wasted his time, and that the intellectual life was a sham. Jackson understood that to mean that the degree earned had been of poor quality and of little use. Symes though had had enough sense to employ a good chef, and Jackson looked forward to his lunch and a quiet afternoon.

Four

Jess decided to spend the day in and around the Village where she was staying. There was an old watering hole on the far side of the Village which she had not yet revisited, and it was high time that she did. She wandered along the main through road, checking out the shops. There was a butcher, a baker, a candlestick maker, two small cafes, a grocers, a chemist, and quite a few so-called gift shops filled with books of the area, calendars, pens, and so on, clearly aimed at the tourist market. In search of the public pathway that she remembered wound around the Village away from the main road, she noticed a particularly beautiful looking dark blue BMW in the main public parking lot. Her interest in cars was limited to whether or not it started on the first turn of the ignition, was reliable, had plenty of oomph under the accelerator when needed, and could corner well. She didn’t care what colour it was, how many doors it had, or what type of engine was under the hood. But she did appreciate a good looking vehicle, and that BMW was a good looking vehicle.

She found the path which led from the car park through the houses and out onto the main street, and across that thoroughfare into the secluded cottages and the cricket pitch behind them, and beyond them into the valley which ran out from the western end of the village. It was sunny, warm and peaceful. And the birds, of course, were everywhere, and singing. Marvellous. She wondered, without needing an answer, why it was that England had so many different varieties of birds, and a consequent wonderful variety of birdsong. She felt grounded, happy, content, and very blessed to be able to walk there. She saw no one. It was perfect. However, after about 10 minutes she came up to the environs of homes located in the nether regions of the valley. Her blissful state abruptly checked, she turned about, and made her way back to where she could take the public footpath up to the church, located on the top of the hill. Before heading up to the church, she sat on the stone wall near the cricket ground for awhile and looked at the green, imagining the Saturday afternoons that the villagers must spend there, watching local teams play. In her imagination, it was always sunny and warm. She remembered the days in her own childhood when she had watched her favourite uncle and cousins play cricket. Well, she thought, there must have been some good times, else how would she come up with these sentimental memories. Shaking herself, she made her way up to the church.

The church was very old. Not big. Usual Norman design, cross-shaped. It was open. That was unusual these days. Inside, it was dark and cool, and musty. Visitors were invited to make donations on an honor basis for the material displayed for sale inside the church: books, bookmarks, cards. Jess left a 20-pound note, and didn’t take anything. She wanted to pay for the privilege of being able to enter the church; so many were locked against visitors. She moved forward in the church to the altar area and gave way to the child in her, and the memory of a time when she had really trusted in a Father God to love her and keep her from harm. She knelt and offered a silent acknowledgement of the memory.

Emerging into the sunshine, she wandered over the graveyard to where Little John of Robin Hood fame was allegedly at rest. A connection to a legendary past which the grave suggested had roots in reality. Little John, according to the legend, had been very tall. The grave purported to mark his height at seven feet.

On leaving the church yard, and walking down the other side of the hill through the cluster of cottages surrounding the church, she passed by the stone-built cottage in which Little John allegedly spent the last of his days. It was from his bedroom window that he allegedly shot his last arrow from his great bow, and asked that he be buried in the ground where the arrow had come to rest.

She remembered how she had wanted to buy Little John’s cottage when it had come up for auction many years ago. One of the detractors had been the very low ceilings in the cottage. She was not over-tall at 5’8”, but the low height of the ceiling beams had required her to keep her head down when walking around in the interior. The thought of that requirement for her, a woman of 5’8”, needing to keep her head down to walk around in Little John’s cottage and, assuming that he did not have to do that, walk around with his head down in his home, just how “little” was “Little John” she wondered.

She wondered what her life would have been like had she bought that cottage and lived there, in Highgate, in the Valley, in a village, in a National Park. Would she have been petrified also, held in suspension, kept as she was then, a kind of tourist attraction, a dropout from the flow of life.

She carried on down the hill to the pub.

The pub looked just the same. On entering, it had the same interior. The Bar was still where it had always been, as were the fireplaces, and the washrooms. But the tables were all set for lunch. There was a very large board on a stand facing one as one entered which had chalked on it the day’s “specials.” There were still stools at the Bar, but there was just one couple sitting there. The rest of the few folks in the place were sitting at tables and eating. There were no loud laughing groups of friends standing and milling about, holding their glasses of beer, and requiring a passage through them to get to the Bar. It was quiet, calm, hushed.

Jess found a table she liked, studied the menu, went to the Bar, ordered her lunch, bought a drink, and returned to her table. While she waited, she looked around and remembered the times she had spent in that Bar so many years ago, the years when she had met with the “in-crowd” there. She felt a sudden deep sadness, a grief for who she had been then. It was as if she suddenly saw through her sentimental memories of “home,” and into the heart of how difficult it had actually been.

As a woman alone, she had made herself go out and meet people, to find the right connections, to try and rebuild her life. In those days, women on their own, especially divorced women, were suspect, treated coldly by wives and girlfriends, and regarded by the men as a likely prospect for a one-off clandestine sexual encounter. She had developed a kind of bravado, and a persona that gained her some respect, and a degree of acceptance with a mixed group of people of her own age. Some of them had inherited their wealth, some had worked to qualify as doctors, solicitors, accountants, farmers, merchants. They were people who were secure, wealthy.

Her first marriage had been a total disaster. She had been abused, shamed, and humiliated by her husband’s betrayals, and then annihilated by her father and her husband in their refusal to help her as they worked together to persuade her to relinquish her children, to give them up into their father’s care, and the care of his new woman, “for their better good,” and of course, for her husband and her father’s financial ease. She was nothing, just a woman after all, and barely that at 25. She had eventually done what they wanted, and had survived somehow. She had found some anger, and had not killed herself, as she expected they had all hoped she would. She had left England after a few years, and made her life around the other side of the world. Her decision to do that had been met with relief; they hadn’t had to think about her again, or tolerate the embarrassment of her presence.

Her lunch, when it finally arrived, was mediocre, too greasy, and way over-priced. She went to the Bar to pay her bill. As she turned to leave, the woman of the couple who were still sitting at the Bar said to her, “It’s Jess, isn’t it?”

Jess, startled, looked at her and her companion, and had no recollection of ever knowing them. “Yes,” she said, “my name is Jess.”

The woman continued “You used to come in here when this place could still be called a local pub. There used to be a crowd of young folk used this place in them days. Nobs most of them. I remember you. Haven’t seen you for ages.”

“Well,” said Jess “I’ve been in Canada for over 20 years.”

“Aah”, the woman said, nodding with satisfaction, “then that would account for it.”

Jess smiled at her, still unable to recall who the woman was, and left the pub.

When she got outside, she burst out laughing and, for just a second, she remembered what it was like to feel English.

As she crossed the Pub’s car park to walk back down the lane to the village centre, she noticed the dark blue BMW driving by on its way up the lane which led out past the pub and up onto the Tops, as the Crags were called locally.

Five

“So, usual is it?” asked Symes.

“Yes, thank you.” Jackson was somewhat surprised that he had the status in Symes’ pub of being known by a usual drink, and felt somehow compromised as a result.

Jackson was aware of Symes’ notoriety, and that there was a local game as to how long one could last in Symes’ Bar without getting banned. He assumed then that his designation as someone who had a “usual” drink meant that he was included in those who were not going to be banned, at least for now. Jackson didn’t welcome the distinction. He was not one to spend time propping up the Bar, so his conversations with Symes had been limited to the odd times Symes had left the business of serving drinks to his staff and had, uninvited, joined him at his table.

Jackson could run rings around Symes’ less than adequate knowledge of the philosophies he had studied, which studies had been a couple of generations ago, and had not been refreshed or kept up. Symes was the type who felt that he knew everything on completing university. He had a tremendous ego. He had seen no reason to continue his interests independently of the need to pass examinations, and any deficiencies in his knowledge were dismissed with a denigration of knowledge. Jackson, on the other hand, had an abiding interest in the nature of humanity, politics, and spirituality, and the evolving of Law and social systems and cultures, religions, and moral imperatives. He read widely, pondered on questions which had no answers, and spent many hours with close friends discussing significant issues, and the state of the world generally. He had the usual university education, followed by post graduate studies at Harvard and Oxford, and several publications to his name in his chosen fields of Law, Psychology and Political Science.

His wife had been the one who had most wanted the academic life in their union. She had derived her sense of place and value from his connections in that community, and her position as his wife gave her a status she felt she was entitled to. Had she been born two decades later, she would have been an academic herself. Instead, she had been caught in the restrictions of her time, before the birth control pill, and in the conventional assumption that she would marry and have a family, or be a lonely old maid and a burden to her father. She had married Jackson, and he had borne the brunt of her frustrated intellectual ambitions. He sometimes mused that had it not been for her resentments at the limitations imposed on her by her culture, he would likely not have worked so hard to be a big wig in the academic world, and could possibly have chosen instead to live out his life as a farmer.

Well, no future in that kind of conjecture.

He was just about 6 feet 2 inches in height, medium build, and in good shape. Some would say that he was a good-looking man. He drew people to him, rather than repelled them. His hair was dark. His eyes were a startling blue. His skin was tanned from his weeks in the Mediterranean. His face was lined. His mouth was ever ready to smile. He had an expression of patience and kindness in repose. In conversation, he came across as diffident, but as someone who would listen quietly and attentively. His calm and steady demeanour reassured his conversant, and relaxed them away from any tendency toward stridency. Those that had the opportunity to speak to him more than once on any particular topic were generally careful to have done the work to collect their thoughts into some coherent representable form before engaging him in conversation again. He was experienced generally as formidably intelligent, but also as kind, gentle, tolerant and patient and, for those who realized it, someone who had no need of anyone.

Symes found him baffling. None of Symes’ usual tactics had the slightest impact on Jackson. For Symes, Jackson was a challenge. In the process of pursuing that challenge, he had tried to get into conversation with Jackson about this and that, feeling he could impress Jackson into a respect for him and his opinions. Instead, he had distinctly felt that his efforts had been merely tolerated by Jackson out of politeness.

He was beginning to respect Jackson and, as a result, had begun to feel less secure in his own God-almightiness. Jackson was becoming for Symes an itch he had to scratch. He moved over to where Jackson was sitting.

“So, where’ve you been today then?” queried Symes.

Jackson turned to look at Symes, who had sat himself down at the same table, with a wide grin on his face, and a pint in his hand. He took a deep breath, and feeling called upon to be civil, responded.

“I took a drive along the Valley and up through a back lane out of Highgate, and along up to the Crags. The view from up there is quite beautiful”.

“Yes, indeed it is” said Symes, proudly, as if he owned the view, “they filmed some of one version of Pride and Prejudice up there you know. And its a great area for rock climbers.”

Jackson had noticed before how insular and proud the English still were, still soaked in a sense of their past greatness. They had been a great nation, there was no doubt about that. At the height of their Empire and its influence, they had introduced into many areas of the world their views on rights and democracy, and common decency, and other less celebrated things that current critical fashion was fond of digging up and pointing out.

“Its not an extensive area” ventured Jackson, “one soon runs out of open country and into the city in one direction, or back down into Highgate and the villages in the Valley, and then Foxend. And then after Foxend, there’s nothing much to look forward to from what I can see…”

Symes was getting annoyed. He expected visitors to the area to have nothing but respect and admiration for his part of the world.

“Its the Valley and the Park that folks come here for, not the city and what’s beyond Foxend,” he said with some asperity. Feeling he needed to impress this fellow from Canada, and put him in his place, he asked “Have you tried fishing at all? We have trout you know in the rivers hereabouts.”

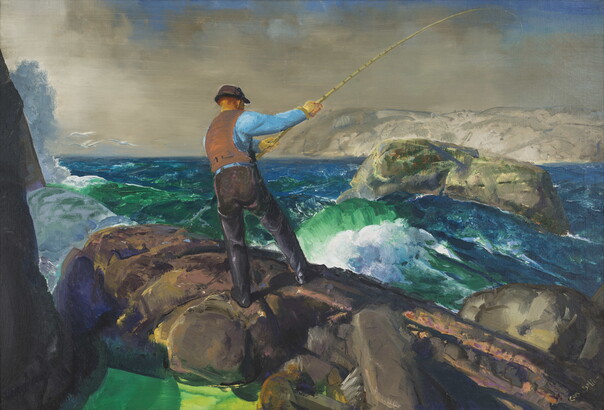

“Fishing? Hadn’t thought to do that here” responded Jackson quietly. He loved fishing. Fishing for him was an opportunity for solitude and to engage with the symbolic. In Canada, he usually arranged a helicopter to take him to a wild and remote river area and leave him there for a few hours while he fished for either salmon or trout, depending on the season and the location.

Jackson, in his usual diffident way, went on to venture that he expected that fishing for trout in the rivers thereabouts must be quite challenging.

“Its great sport” said Symes, “if you want to try it, I can arrange something for you.”

“Well, thank you. I’ll think about that”, responded Jackson.

There was a halt in their conversation while Symes attended to the needs of a group of young people who had noisily entered the Bar.

Jackson wondered why it was that mixed groups of younger folk made so much noise. Probably hormones he mused. The younger women seemed to shriek their exclamations of affected outrage, and laughter. He had seen one of the women before, more than once, and it was clear that she was enamored with Symes. She had stood a little apart from the group, and stayed at the Bar when her friends moved to sit at one of the tables. There had followed a few minutes of what looked like an urgent and intense talk with Symes before she rejoined her friends.

Jackson noted that Symes looked annoyed after his exchange with her.

It had been clear to Jackson for some time that Symes was involved with several women who came into the Bar. After some thought, Jackson had come to the conclusion that the women who were enamored with Symes were likely seeing what they wanted to see rather than the reality. Symes’ arrogance could come across as strength and independence, and his ownership of an apparently successful business as evidence of maturity, expertise and competence.

What Jackson could see in Symes was desperation. It was clear that Symes had no respect for any of the women he associated with. For Jackson, that signaled that Symes had no respect for himself.

After a few minutes, Symes returned.

“Stupid woman,” he muttered, and then laughed, looking at Jackson with an expectation that he would agree, and share in his disdain. Jackson raised his left eyebrow, and looked at Symes through narrowed eyes, with no hint of a smile. Symes shrugged and laughed again, feeling very uncomfortable, and on the excuse of his presence being needed at the Bar, took himself off again.

Jackson moved to one of the more comfortable wing chairs in the lounge. He planned to finish his drink in comfort before tackling lunch, but Symes again came over to where he was sitting and asked, “Well, would you like to try some fishing then?”

Jackson sighed, and turning to look at Symes out of squinted eyes, said, “I get the impression that you like fishing”.

“I’ve been known to catch the odd trout” responded Symes, ignoring the distinct impression he had that Jackson had meant something else, “and there are some superb spots for fishing in the valley, if you know where they are. I’d be happy to show you if you like.”

Jackson couldn’t imagine there being any pleasure in spending any length of time with Symes. He wondered why on earth Symes was approaching him in this way, prodding, and seemingly needy of his approval. He wondered what was driving the man. Could Symes actually be feeling the need to change his ways? Was he, Jackson, supposed to help Symes in any such transition? Was there any way he could enjoy fishing with Symes as a companion?

“What is it about fishing?” he asked “that captures our imagination so. Have you any idea?”

“Hadn’t thought of it as being about imagination” responded Symes, laughing, “its just about catching fish! Maybe you folks from Canada have to imagine catching a fish, but we here in England, we actually catch the buggars!”

Symes was in his element: pride of place and putting a foreigner down.

Jackson smiled. Symes was indeed very needy, and this invitation to go fishing was turning into a personal challenge.

“Well” Jackson said, “its good to know you still have fish in your rivers here, and that they are safe to eat. I couldn’t possibly join you though, I don’t have any fishing gear with me. But thank you for the invitation.”

“I’ve got fishing gear. I’m sure I could fit you out. What do you say?”

“Well, that’s very kind of you I’m sure, but I don’t know when I would have time to spend an afternoon fishing, and I am sure your free time is very limited. I’m thinking of taking a trip up to Northumberland before I go back home, so my schedule is pretty full,” said Jackson.

“We could go tomorrow afternoon” responded Symes. Jackson remembered that he had arranged to book out of his room the day after tomorrow. Feeling now that he could hardly continue to refuse the invitation without causing offence, and feeling a strange compassion for Symes, he decided to go along.

“Alright then. What time?”

“About 2 p.m. if that’s convenient for you.”

“2 p.m. it is. I’ll meet you here in the Bar?”

“OK, that’s good” responded Symes, feeling restored.

“Time for me to get something to eat” said Jackson, “maybe there will be trout on the menu!”

And he picked up his drink, and started toward the restaurant.

“The restaurant won’t be open until 6.30 this evening” said Symes “but I can arrange a bar meal for you.” and he handed Jackson the menu.

Jackson resigned himself to something else with the ubiquitious “chips,” and ordered a prawn salad sandwich—with “chips.”

He consoled himself with the thought that he would at least have his book for the afternoon.

Six

Jackson had realized not long after his arrival in the area that he must be in Jess’ old stomping grounds. He remembered her talking of Highgate and the Valley. He remembered her talking about it with fondness and lingering nostalgia for times she felt had been good to her. Being in the area where she had spent her life before her path had crossed his, made him feel closer to her. He knew it had been in her time here that she had been in deep dark water, and that it had been on leaving here that she had somehow managed to swim her way back up to a shore of consciousness and balance, to a deeper understanding of God, and back to a commitment to life and carrying on, back to finding pleasure and appreciation, and back to loving.

The countryside was gentle, very green, benign. There were no dangerous animals here, not even a dangerous insect. The worst pestilence, if it could be called that, was to come across a cloud of midges under dark damp trees on a hot day. Something easily avoided.

The buildings were stone built for the most part, and generally no more than 2 floors. In the valleys, closer to the big city, there were some old factory buildings which went up to maybe 5 floors, sometimes 8, but they were the highest buildings, and converted to very expensive apartments now. In the countryside, it was all smallish cottages, stone built, very old, weathered and worn, and perfectly melded into their environment. Some had gardens at the front, some did not. Some stepped straight onto the street. No doubt they had gardens at the front of the property at one time, when only a horse or two went by, and then the way was widened to accommodate carriages, and then widened further to accommodate two carriages, and then, there they were, with front steps onto a narrow sidewalk bordering an increasingly busy road.

There was a sense of peace, stability and permanence, as if the world had passed the area by. Each village had a church, usually on a hill. He had visited some of them and found that they were still relatively well attended, obviously supported and lovingly cared for by their respective congregations. The graveyards around the church were well looked after for the most part, the grass cut, fresh flowers at some of the graves, and the inside of the church itself was generally clean and tidy, with fresh flowers on the altar. From the notice boards it was possible to gather a sense of the community life still centered in and around the church and its congregation. He was impressed and comforted by that.

He had been back to the village she had mentioned more than once, and the pub. He had taken the drive she must have taken to get there from her home on the outskirts of the nearby city. He had tried to imagine how the countryside had affected her. There was one point in the drive where the road ran along the top of the moor separating the city from the valley and then, quite suddenly, the road crested the edge of the moor and the valley was laid out beneath one. It was a spectacular view. The road then turned down into the valley and ran into the village and right by the pub. He stayed very conscious of how the drive affected him, and he tried to translate his own feelings into her experience. He had known her very well.

Jess had been a colleague for many years. She was tall, with a slender toned body, fair hair expensively cut into a flattering short bob, green eyes, a straight nose, high forehead, and a complexion that would do justice to all the myths about English women and their skin. She was a very attractive woman, and a complex, interesting, very intelligent woman with a traumatic life history. Someone who knew the reality of “the Other,” and who had grown to understand and accept ego defeats as an indication she had lost her way. She had known from experience that she was not just her ego, that her ego was a construct, a defence, a reaction, a kind of complex through which her larger Psyche would express itself, if it were allowed, and that she was more than what had happened to her, that there was something that might be called eternal within her, and she wanted to be connected to that more than anything else.

They had talked of the Garden of Eden myth, and how it expressed a truth of soul, and how, perhaps, her journey was an effort to get back to the Garden. She had said it was not. She had understood the Garden myth to be for children. She felt that everyone had to leave the Garden, eventually.

She had always behaved toward him with the utmost respect and dignity and he had come to understand, with some regret, that it was more important for her that he always act in a way that would not compromise his own integrity in his marriage than to have him act on any feeling he might have for her. It was why, when the job offer came of a teaching post at Harvard he had accepted it, knowing that it would take him away from her.

His wife had been content to leave him be, and he had no wish to hurt her, or astonish his children. It was the way it was. But he had loved Jess. They had never expressed to each other how they felt, but he knew she knew how he felt, and there had been enough times when it had been clear to him that she returned his love. They had kept their experience perfectly preserved from the contamination of hurting others. They had loved each other enough to let each other go rather than drag each other, and those others they loved, through the muck and mire of divorce and brokenness.

He hadn’t seen her for almost 10 years. He chuckled when he thought of that. 10 years. Goodness. Perhaps he was getting sentimental in his dotage. He was heading up to 60 now. He expected he would retire in about 5 years, then his life would be split between his home in the city, and his retreat in the wilderness. His country was so different to this England. It had none of England’s benign gentility, but was spectacular, harsh, rugged, and potentially dangerous.

The rain was different here. It mostly drizzled down in a gentle mist. The greens of the grasses, plants and trees were luminescent, brightened as if lit, in the light of the water. The rain caressed and nurtured the land. Where he came from, any misty effect from the rain was as a result of the ferocity of the bouncing spray from tremendous, almost malevolent downpours. The roofs would look white, as if covered in snow. The rain was driven and relentless, a felt punishment for having dared to have a summer. As in much else in his country, the plants either stood up, determined to survive and take as much benefit from the deluge as possible, or they drowned.

He had taken to going quite often to the edge of the moor on the road along the Crags and to the view of the valley laid out below. On some days it would be bathed in a low-lying mist which caressed the bottom slopes, leaving the crags clear and floating. The light would be divine, the sun streaking through low stretched clouds and laying its beams softly on the landscape. He would stop the car and sit for a while. He imagined she must have done that. He was sure she had. It was a tranquil yet breathtaking prospect, and he could feel the deep peace swimming into his body, and relaxing his mind. Yes, he could understand her lingering nostalgia. He also realized that her spiritual life must have been deepened with such experiences. He remembered seeing a program on television called Landscape as Muse, and began to understand more deeply the connection between environment and spirituality.

Jess had been raised with an image of God as exclusively male, all powerful, all knowing and allegedly all good. He chuckled to himself as he remembered with pleasure the hours they had spent talking theology; the long debates on the dogma of God’s goodness and omniscience, on the doctrines of election, free will, and predestination, about Fate and whether it was different from Destiny and, if so, what made that difference. She had struggled to find a cohesive theory which would fit into her life’s circumstances and experience, and still maintain the patriarchal image of an all-good god. She had tried desperately to stay faithful to the tradition in which she had been raised, to make sense of her life in its context but, in the end, she had been forced to abandon the hope of a kindly, powerful protector, a god of contracts, and accept a different reality, a more demanding reality. He felt her courage in relinquishing the safe god of her childhood in coming to an honest and fearless understanding of God which better fitted into the events of her life and made sense of it all, had been her biggest struggle, and her biggest achievement. She was, in his view, a mature Christian who would journey on.

He wondered if he would ever meet her again. He had thought about trying to find her, to find out where she was in her life. He had dismissed the thought as romantic nonsense. The last 10 years had changed him, and would have changed her, and any meeting now could be embarrassing and awkward. He preferred to keep his memories.

Seven

The day to fish arrived.

Jackson met Symes in the Bar. He had accepted, and come to terms with having to endure Symes being in control of their adventure. He had entertained the possibility that he might find some sport fishing on his travels around Europe, but had decided against bringing his gear on the basis that it put him way over his baggage allowance, and would likely get lost or damaged in transit in any event. Symes had indicated that he would have enough fishing gear to loan to him to adequately equip him to fish in what Jackson anticipated would be limited surroundings, and for a short time, but he was used to his own gear and felt somewhat irritated by the whole thing.

Symes was full of himself. He was strutting around in the Bar, dressed in an old green multi-pocketed jacket and a floppy hat of an indeterminate colour which had various flies pinned to its headband. He was carrying two pairs of waders and boots. There were rods propped up against the corner by the door. When Jackson appeared, Symes visibly expanded, and advised the sparse attendees at the Bar that he was about to show this Canadian the beauties of the English river system, and would they please excuse him. He then turned to Jackson, with a grandiose and mocking bowing gesture, and asked him to please follow him to the car. Jackson, allowing this show, smiled, and stepping aside, he opened the door to let Symes sail through the door ahead of him and then turned to give his own bow to the assembled before exiting himself in Symes’ wake.

Symes led the way to his vehicle, which turned out to be a sand-coloured Range Rover. The fishing gear was stored in the back, and Jackson was invited to occupy the passenger seat in the front. Symes drove quickly through the valley roads of his locale, and out from there across the Upper Moors area and into the far end of the adjacent valley until they were close to the area of the Hope Estates. He parked the vehicle in a secluded spot not far off the road, and started to unload the gear. Jackson helped him, and between them they sorted out which rods and which waders would best fit each one of them. Symes then led the way through the trees, and down a slope, until they came to a river bank. He indicated that this was the spot they would fish from, and he and Jackson set about preparing the gear, and equipping themselves for the challenge of the river.

Jackson was amused at the prospect of the river being part of the Hope Estates, and he wondered if it was possible that he was about to commit a crime in fishing there, and what the fine would be. He decided, under the circumstances, that it was likely something he would have to leave to Symes’ local knowledge, and trust that Symes would not be so foolhardy as to expose him to a potential criminal charge. However, such a trust, he realized, was likely foolhardy. He smiled to himself at the thought that he likely wouldn’t catch a damn thing in any event. However, the intent to do so was enough – not a good note on his resume.

He decided to ask Symes, “is this part of the local landlord’s Estates then, this river?”

“Could be,” said Symes, “but it’s not clearly marked, if it is. There are no signs. Its readily accessible. So I assume it’s OK to fish here. Lots of other folk I know fish here, and there’s never been any trouble.”

Jackson felt these were good observations.

“So, you fish here a lot then?” asked Jackson

“Oh, yes,” said Symes, “whenever I come out to fish, I generally come over to this area.”

Symes moved along the river bank a short distance and announced, “I’ll take this spot, it’s my usual one, and I suggest you go up a bit to find your own. Let’s see who catches the most! Off you go, unless you need my help in casting your line? I can show you how to do that if it’s a problem for you.”

Jackson smiled an acknowledgement, and made his way up the river, wondering if the afternoon could turn out well enough after all. He found a spot some distance away from Symes, and across from where trees, on the opposite bank, were providing some shade over the water. Spotting a cloud of midges under the trees, he expertly cast his line into that area of water, and then relaxed into his solitude in the perfect place of river, sunshine, the light on the water, the birds singing, so many different kinds of birds in England he had found. That variety of birdsong was the one thing that endeared him to England, that and the almost luminescent green of the fields all around him. His inner equilibrium and peace restored, he felt content.

He was putting his second trout into his basket when he saw that Symes was making his way toward him. He cast his line again and waited.

“So” called Symes, “how’s it going?”

Jackson waited until Symes had drawn a little nearer.

“Not so bad” he said, “not so bad.”

“Well, there’s nothing doing down there” said Symes, “I thought I’d come and see if you’re having any luck.”

“Just a couple, so far,” said Jackson.

“You’ve found a good spot then,” said Symes, sounding almost exultant, “I should join you,” and, standing just a few feet away from Jackson, Symes cast his line into the same area of the river.

Jackson felt annoyed. The peace was gone.

After a pause, he said “there’s definitely something symbolic, don’t you think, about fishing, ever thought about that?”

“Symbolic! You’re joking right?” Symes laughed.

Jackson was wondering why he felt the urge to annoy Symes on such a day, and particularly while fishing, which was a sport he very much enjoyed. Perhaps it was that. The sport of fishing was somehow contaminated by the presence of Symes and his competitiveness. Jackson felt the urge to puncture that arrogant mocking derisive manner that Symes carried around with him, humble him somehow into a deeper appreciation of where they were, and what they were about, and also to ensure that Symes had not mistaken his coming on this trip as being evidence of a desire to be one of Symes’ favoured circle.

“Well, we stand here,” said Jackson, as he adjusted his position, “up to our groin in the water, casting a line and hoping to pull something up out of the depths. We may succeed, we more often do not. We can stand here for hours, waiting. That gives us time to reflect, to let our minds wander, to contemplate, to absorb our surroundings, to relax the agitation of the conscious mind, to wait and see, to let go, and see if anything comes up.”

Symes was beginning to feel uncomfortable. He knew this Jackson was different and someone he could acknowledge, if only to himself, as a superior sort of bloke and, because of that, someone he felt compelled to best; to try to conquer and put down. His plan had been for this to be his day to shine, to show off the river, and to catch some trout, to put this foreigner from one of the colonies in his place. Now he felt challenged. Not only had Jackson demonstrated his skill with a fishing rod, but now he was bringing up that sort of philosophical stuff that Symes always felt intimidated by. He could see his plans for a day of puffed up superiority fading fast. Damn and drat the whole thing. He realized that this effort to assert himself, to best someone who he knew was independent of him, beyond his reach, was going to backfire. Symes started to feel deeply annoyed.

Symes re-cast his line.

Jackson continued, “water, as I expect you know, is generally considered “female” in symbolism. We talk of the sea in that way. Ships are generally given female names. And the sea is a symbol for the unconscious, that out of which we all came; our beginnings if you like, the Mother of us all. Evolutionary theories support this. A man or a woman, when he or she is on his or her “hero’s” journey, a journey to differentiate him or herself from his or her beginnings, can associate Darkness with the Feminine, feel it is something alien and hostile, something he or she has to fight free of, dominate, control, an unknown quantity, something he or she struggles against, feels he or she has to assert him or herself against. We all come out of the Feminine. Some call that process the development of consciousness, or ego.”

Jackson paused as he watched Symes adjust the lay of his line. Symes was understanding what Jackson had said, but wondered where it was going.

Jackson continued, stretching out his left arm to take in the river, “I remember seeing a drawing once of the figure of Christ with a fishing line. At the end of the line, suspended in the depths, was a fish. The fish symbol is generally associated with the Christian religion. I expect you knew that?” queried Jackson.

“Yeah, yeah, I knew that!” responded Symes, sounding exasperated, “I’ve seen cars about the place with a fish symbol on the back, I expect its about that.”

Jackson continued, “you know, the Christian religion can be seen as a kind of personal growth program. The fish would represent a content of our psyche, swimming up from the unconscious into our conscious minds, a content that we had previously been unaware of, a piece of knowledge about us, about our soul, about our larger being, that we can pull up and integrate into our conscious understanding of ourselves and so become more integrated, more whole.”

Symes, feeling very nervous now, out of his depth, and threatened, though he was a long way from understanding why, laughed, pulled on his line a few times, and in his usual defensive aggressive manner, felt the need to belittle and deride what Jackson had said. He responded with a glib “that sounds like a load of fantastic claptrap, along the lines of all the claptrap I had to put up with at University. I prefer to keep to fishing as just relaxation, with nothing symbolic about it. We just need a goddam trout to eat for supper tonight, and that is all.”

Jackson laughed. “As you will,” he said. He realized he had unnerved Symes, and had maybe achieved his objective. He resolved to make no further efforts. Enough was enough. They fished in silence for a time.

Symes was thinking over what Jackson had said. Symes had no time for religion himself, but he was interested in finding that Jackson clearly did. He knew Jackson was no fool. He was wondering how to broach the subject again when he felt a tug on his line and all his attention went to reeling in and bagging the trout he had snared.

“Anyhow,” said Symes, his trout safely stored, and as if there had been no break in the conversation, “nothing good ever came out of the Feminine if you ask me. Nobody lives like they used to do. The women are out there working, voting, and refusing to do what their men tell ‘em. Gone are the days when women knew their place.”

“Women asserting themselves has certainly contributed to the decline of male authority,” agreed Jackson, “and with the decline of the patriarchal religions, and their authority to impose a role on the man, men are free to break out of the role of provider and head of a family if they want to.”

After a pause, in which he attended to bagging his third trout and re-casting his line, Jackson continued “Indeed, from what I’ve seen over the years, it seems to me that many men never wanted that responsibility in the first place, and never fulfilled the expectations of them.”

“So, nobody’s perfect,” said Symes angily. Symes was feeling picked on. It was as if Jackson knew about his past and that he was one of the men who had not fulfilled his obligations under the patriarchy and was, accordingly, one of the men who had contributed to its erosion, even though he did, of course, continue to expect to be dominant in his relationships with women. Out of his discomfort, and wanting to defend his past actions, he said contemptuously, “Well, women wanted their independence, now they’ve got it. It’s about time they had to pull their weight instead of sitting around at home expecting to be looked after.”

Jackson adjusted his line.

“Your mother didn’t work then?” he asked, gently.

“No, she didn’t,” said Symes, “she sat around at home reading novels and smoking cigarettes, and she bossed my Dad around. On pay day—he was paid in cash in those days—he had to hand over to her his whole pay packet, unopened, or he would get treated to her anger—and fearsome temper. Believe me, she knew how to make you miserable. I hated her.”

Jackson felt uncomfortable at having provoked this outburst. Symes meanwhile went from a strong feeling of justification and anger to feeling exposed and vulnerable, and wishing he hadn’t said anything.

“I’m sorry,” said Jackson at length, “you must have had a difficult childhood.”

“You could say that.” said Symes.

“I’m sorry,” said Jackson again. “Was she an intelligent woman? Sounds like she did a lot of reading.”

“Yes, she was bright enough,” said Symes. “Never got a job though, never used her brains. Mind you, when I was growing up, my Dad would have felt ashamed if his wife had a job.”

“And there,” said Jackson, “could be the source of her problems, and your problems with her. I don’t expect there were many opportunities for your mother to develop her intellect in her day.”

“Well, she should have done something about it.” sneered Symes, “It wasn’t my fault.”

Symes was feeling increasingly uncomfortable and irritable. He had never told anyone so much about his mother before.

“It would indeed be a better world if each of us identified and dealt with our own problems, and resisted blaming others for them,” said Jackson gently, “but you have to acknowledge that we haven’t made it easy for women to make their way in the working world”.

Symes was feeling more and more out of his depth, and his usual reaction to feelings of that nature was to attack. “So, you’re interested in religion, and psychology. All rubbish in my opinion,” he said, laughing, “Strange, I was sure you were an intelligent man!”

Jackson smiled at Symes, and then turned his attention to his line, which was biting. Symes suddenly felt exposed and stupid. After a few minutes, Jackson landed his fourth trout. He then turned to look at Symes again and said, “Yes, I am interested in religions, and the way the religious instinct in us all is worked into those containers, and into our cultures. It’s impossible to properly understand a culture without understanding its religion.”

“Well, I wouldn’t say England is a religious society these days,” said Symes, gruffly, “most of the churches are being turned into flats, or just knocked down; nobody goes to church any more. So what does that say about England? A bloody god-forsaken place I expect. Certainly feels like it at times.”

“Well, I understand the church is a dying influence in the cities,” responded Jackson. “Changing times are likely more immediately felt in the cities but. while I’ve been wandering around the locale here, it’s clear that some people still hold on to the old ways, go to church, invest in a community built around the church, and that there is still fellowship to be found in that, and that surely has to be a good thing.”

“Umm I suppose…” said Symes, feeling less defensive, and a need to be more agreeable, “but they are a minority. And they can be a pesky lot of self-righteous, judgmental, small-minded scaredycats to boot. I’m sure the vast majority of the population here are through with that Christian stuff. Nobody with any intelligence takes it seriously any more.”

“And why is that, do you think?” queried Jackson.

“Well, that God of theirs, what use is he? Look at all the wars in the world, the horrible things that go on. We know now what goes on over the hill there, and in other parts of the world. How can anyone believe in a God of justice and goodness when there’s all that shit going on. It’s ridiculous. I reckon he did himself out of a job?”

“Our understanding is in transition,” said Jackson “we are always, I hope, growing in our understanding. There is a lot of psychological evidence out there now to support the theory that there is an entity that is transpersonal, and that there is a religious function in each and everyone’s psyche, and that function will find its expression in a projected form if it is not recognized for what it is. When its projected, what actually belongs to that transpersonal entity can be misplaced in beliefs in humanity’s power to control everything, including the climate, and can find a home in materialism, communism, humanism or the latest, and possibly most dangerous and challenging, Islamism.”