by Kathleen Glassburn (December 2020)

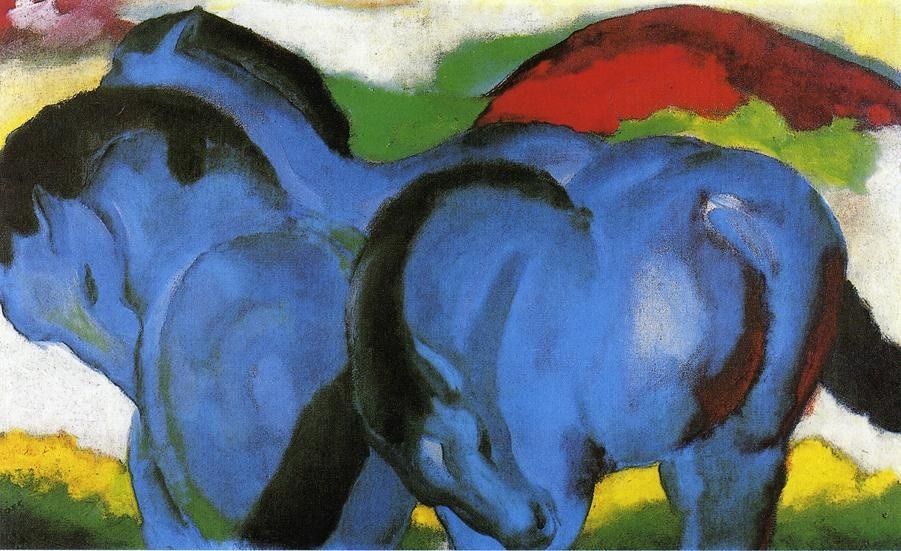

Large Blue Horses, Franz Marc, 1911

Friday night, after a strenuous hike, my family and I sprawled in the main room of our Colorado mountain cabin. My exhaustion from the exercise, as well as turmoil earlier in the day, numbed me, but I wondered, Will I be able to sleep tonight?

Dinner of barbequed burgers had been devoured and dishes handwashed. Our clothes smelled of smoke from a campfire, our mouths tasted of sticky, sweet s’mores. Without television or internet, we discussed playing a game of Hearts before bedtime.

Instead Melanie, our twenty-year-old daughter, started a conversation that cancelled out any plan for cards. “What do you guys want to do more than anything else?”

“I want to take a trip to Normandy. See the D-Day beaches,” Ron, my husband, said.

D-Day beaches? They’d never interested me. It sure would be a relief to get away for a good long while. That’s impossible, was my next thought.

“I want to write a thriller,” Sean, our eighteen-year-old son, said. “A bestseller!”

Write? I’d never heard him express an interest.

“I want to start playing the cello,” Melanie said.

Cello? She’d played the piano as a kid.

After a pause Melanie said, “How about you, Mom?”

“I need a new activity—to get my mind off . . . well, you know . . .” I’d recently quit my position as an elementary school librarian to look after my widowed mother.

Having witnessed my morning meltdown in Woodland Park, they murmured, “That sounds great,” and other words of encouragement.

“I could volunteer teaching English as a Second Language.” With a master’s degree in Library Science, this seemed feasible. I pictured myself in front of a classroom of students, no matter how eager, and cringed.

“That’s a great idea,” Ron said.

“Or I could get back to horseback riding.” I hadn’t ridden in over twenty years but remembered the thrill, the fun, and the communication teaming up with a special horse.

“Audrey! Isn’t riding awfully dangerous at your age?” Ron blurted out.

“Jeez, I’m barely fifty. I used to be pretty good—never took a fall.”

“It’s a great idea, Mom. You should do it,” Melanie said.

“Consider your shelf life.” Sean sported his teasing grin, redeeming himself with, “You can always teach ESL when you’re not in such good shape.”

For the rest of that weekend, I kept thinking of all the horses I’d known. It took my mind off an alcoholic mother.

Upon returning to Denver, I wrote in my journal: I want a fifteen-hand, lovable, easygoing mare. A couple weeks later, despite Ron’s warnings, I started lessons.

* * *

On the morning of our “wants” conversation, I stood in a Woodland Park lot an hour away from our cabin. My husband and son had taken off to buy groceries.

“I’ll only be a few minutes.” Melanie strode toward the drugstore to buy shampoo for her long, silky, blond hair.

Meanwhile I made a call back to Denver to check on Mom. Without telephone service at our mountain getaway, I had been out of touch since the day before.

In her mid-seventies, she couldn’t be counted on to clean her house or change her clothes or brush her teeth, let alone take a bath. However, deeming herself completely capable, she’d dismissed the women I hired to help her. After three automobile accidents, with Mom throwing a tantrum worthy of a two-year-old, my husband and I, feeling like grade-school bullies, confiscated her car. Lapses when she missed social engagements with friends and family happened regularly. Ron and I configured a two-room suite with a private bathroom in our house for her.

She refused to move in with the excuse, “I want to preserve my independence.”

For a long time I was in denial regarding my mother’s drinking problem. She hadn’t been much of a drinker before my father died. Now I came to the conclusion that she wanted her alcohol without any watchful eyes.

When she was sober and I talked to her about troublesome events and bad behaviors, she insisted, “Those things never happened.”

A few weeks before our trip to the cabin, at the urging of her physician, I moved Mom into an apartment at Centennial House, a retirement and assisted living facility a few blocks from where we lived. They took excellent care of the residents, wanting them all to reach at least one hundred years of age.

Eventually Mom had agreed to making this change, but to describe her attitude as mercurial was an understatement. Sometimes she said, “This move is a great plan.” Hours later she said, “They’re going to take me out of my own home—feet first!”

* * *

In that shopping center parking lot, I grasped the cell phone closer to my ear. “What do you mean she’s gone?”

“Your mother contacted Starving Students Movers,” the man who was head of the facility repeated. “Yesterday they packed up the apartment, and she returned to her own house.”

“I can’t believe this. Couldn’t you do anything?”

“The police came when she called 911 numerous times. Your mother kept telling them she was being held against her will. Of course, this was false. She has been walking to the store on her own every day.”

He didn’t say to buy wine.

“The police told me what I already knew. If a resident states that they want to leave, there is nothing we can do. I am sorry. I know this is a tremendous worry. Truly, we tried in every way to talk her out of it. She would not be dissuaded. As a side note, she called our dining room last night and demanded that her dinner be brought to the apartment. Our chef reminded her that she’d moved back to her own house. Your mother banged the telephone down so hard it hurt his ear.”

After I ended the call, my breathing came faster and faster. Am I going to hyperventilate? Cars and stores blurred as I leaned against our SUV for support.

“Are you okay?” Melanie, a bag in one hand, grabbed my shoulder with the other.

I haltingly explained her grandmother’s latest debacle. “She waited until we were gone to carry out her plan.”

“Let’s go in that restaurant and order a cold drink. It must be ninety out here.”

For half an hour we hunched together in the Hungry Bear Café, waiting for Ron and Sean to show up. Air-conditioning cooled my skin as my agitation continued to feel like a kettle boiling over.

“What’s next?” Melanie asked.

“Nothing.” I shook my head. “There’s nothing to be done. In a sober state she still functions well. This move from Centennial House proves it.”

“Why is Grandma doing these things?” Melanie looked on the verge of tears.

“Being by herself to drink without observation is more important to her than anything or anyone else.” I put my head down on bare, crossed arms. They stuck to the Formica tabletop.

Melanie waited with me until Ron and Sean found us that way.

We stayed for our long weekend at the cabin, and Monday morning, back in Denver, I visited my mother at her house. The broken railing on her once meticulously maintained porch looked precarious. If only there’d been enough time to sell this place. I decided to ask my husband to do another repair job.

Inside Mom greeted me as if nothing unusual had occurred. “You’re looking well, Audrey. I hope you had a good time at the cabin.” Beside her chair in a basket were bunched dusty pieces for the quilt she’d been working on when Dad had his unexpected heart attack.

“I did.” Deciding to charge right in, I continued, “Why did you move from Centennial House, Mom?”

Eyes on her hands, as if she was counting every spot, Mom said, “I’m staying in my home ’til my end.”

* * *

The day of my first riding lesson, I kept hopping up from the kitchen table to get the newspaper, a notepad, a pen, my eyeglasses. Breakfast of yogurt, an English muffin, orange juice, and coffee eventually got eaten. A few minutes after finishing it, my stomach churned.

Maybe Ron’s right.

What did I remember about riding a horse? I couldn’t think of correct position or signals—“aids” I guessed they were called. Instead I recalled the runaways on a Thoroughbred named Timberlane or “Timber.” He was my last horse before retiring my boots in favor of comfortable slippers to wear when walking a screaming infant.

I told myself, Timber couldn’t help it. He was bred to race. Then I rationalized, They’re not going to put me on a horse like him.

Pine Meadows, the stable, was a thirty-minute drive from our Denver house. I listened to classical music in my Subaru on the way. I’d heard that the usual sixty beats to a measure calmed a person—like heartbeats. Brahms’ “Lullaby” came on and I smiled.

Jackie, the barn manager, greeted me at the office door. About thirty-five, she wore a red plaid shirt, gray riding breeches, and black riding boots. “Here, this helmet should fit you.”

“Back in the day we never wore helmets.”

“More into safety now.”

This eased me somewhat.

“If you decide to continue, buy one of your own.”

She handed me an application to fill out.

On the line asking about experience, I indicated it had been twenty years since I’d ridden. “I used to be pretty good. Hope I haven’t forgotten,” I told Jackie.

“You’ll be fine.” Her blue eyes twinkled.

How many newbies does she reassure? “I’ve never seen an Injury Disclaimer.”

“It’s standard—cover-our-asses. The horse I’m putting you on is super reliable.”

The once-familiar smell of hay and manure relaxed me. How come a stable smells so much better than a cow barn?

Jackie looked at my hiking boots. “If you continue, you’ll want to buy riding boots too.”

“I plan to continue.”

She gave a little snort.

I handed her the filled-out papers, wrote a check for $60, and followed her to the aisleway that circled the arena. It had been advertised as one hundred feet by two hundred feet. I saw jumps arranged throughout the vast expanse.

Even though I’d jumped Timber at three feet often and won several ribbons, at present I was scared about even taking a horse out of its stall. In the past my feet had been stepped on, and in a horse’s haste I’d been pushed up against walls—always because I was distracted.

There were about forty horses munching their morning hay.

Jackie stopped at the stall with a brass nametag saying “Sunny.” A good sign.

“Stand back and I’ll take her to the crossties,” Jackie said.

Fine by me.

Sunny was about fifteen hands. A shiny chestnut, she had a white star between her soft, brown eyes. She looked at me with interest and I stared back.

“Are you okay grooming her, picking her hooves, and saddling her up?” Jackie asked.

“I’ll manage.” I hope.

“If you need help just ask.”

All during the process Sunny remained still, and the tacking-up readily came back to me.

“Let me do the bit,” Jackie said. “It’s the hardest part.”

When she was ready I led Sunny into the arena, glad that Jackie walked next to her on the right side.

Once at the mounting block, Sunny stood quietly, waiting for me to get on and situated. I took a deep breath and she took one too.

Jackie stepped away. “Give a little pressure with your legs and ask her to walk.”

It barely took any leg at all. Sunny knew her job and, throughout the rest of the lesson, automatically did everything I asked her to do.

For almost the full hour, Jackie instructed me to walk straight and in circles and across the arena and, most importantly to halt, calling out words like, “Nice position,” “Looking good,” and “Terrific.”

When there were about ten minutes left, she said, “Do you want to trot?”

“Sure. I can do it.” Posting came back to me immediately.

“You’re going to do great,” Jackie said after I tacked Sunny down and put her in the stall. “Next time maybe you can canter.”

I gushed my thanks as I left the barn. Sitting behind the steering wheel, I thought, This is like being twenty years old!

And then, I haven’t worried about Mom for hours.

* * *

So Sundancer came into my life. At the end of each ride, I gave her a kiss on the star and praised her. I also brought treats and sang kid songs to her. She seemed happiest with “You Are My Sunshine.”

I rode other horses but she was my favorite.

After a couple of months, Jackie asked, “Would you like to buy Sunny? Her owners have moved several hundred miles away.”

“I’ll let you know after I talk to my husband.”

Ron readily agreed, saying, “It’s expensive but I can see how this helps take your mind off your mother.”

Sunny was older, at thirteen, and smaller than other Warmbloods in the stable. Maybe these characteristics made her pick up the pace when competition horses were in the arena. They probably found her racing after them to be amusing. I laughed at the way she followed a zippy white pony that ran like the dickens. Sunny loved to do flying lead changes. I called this her “show routine.”

There were plenty of times when she was fresh and frisky. “Full of sparkles,” Jackie said. Often I watched her playing freely in the 20,000-square-foot arena. She kicked up her heels like a filly and her chestnut coat glowed.

No matter how bad I felt driving out to the stable, no matter what scary or frustrating or overwhelming situation had transpired with Mom, my attitude lifted as soon as I saw Sunny. I put my bare hands on her strong body and my shoulders softened.

One fall afternoon I got my first call of many from the security company whose system I’d had installed at her house, against my mother’s better judgment.

“The smoke alarm went off,” a woman said. “The fire department is going to that address.”

Rushing to Mom’s house a few miles away, flaming autumn leaves seemed to fly by the windows of my Subaru.

“Your mother is lucky we’re only five minutes from her,” the fire chief said. “A little more time and the kitchen would have been engulfed.”

Blacked out, she’d left eggs cooking on the stove. Mom lay on her living room sofa, mumbling something about being fine.

I went out on the ramshackle porch to talk in private.

“I don’t know what to do. She won’t allow anyone to help her. She wants to live here by herself.”

“This happens sometimes,” the fire chief said.

“You could put her in a seventy-two-hour watch at the hospital psych ward,” a young female medic said. “They would ascertain if she is able to live independently. I can take her in.”

“Maybe in the future.” How can I institutionalize my mother? Besides, she’d be sober and lucid the whole time.

After a horrid night where I pictured Mom burning to death, I checked on her and then went out to be with Sunny.

By the time I combed my horse’s thick, red mane and tail, it felt like her big heart had linked with mine. My cares momentarily floated away like fog rising from a mountain meadow.

As the years went by, Sunny became even more cooperative during my time with her. She stood motionless and proud after I dismounted, as if waiting for a wreath of roses. I became a better, more patient rider and, I hoped, a better, more patient person.

Mom’s binges increased and it took all the patience I could muster dealing with unpaid bills and household filth and complaints from her neighbors.

* * *

Sunny had never been a particularly nervous horse, but once she turned twenty, spooking at anything unfamiliar started. A few times she dumped me. I wasn’t severely hurt, merely banged up. I wondered if her vision was compromised. Two-foot hurdles, which we had regularly jumped, were rearranged often. Maybe they’d begun to look more dangerous. I took to leading her by hand both directions before mounting to show her anything that might be disturbing. I quit jumping her and I bought a safety vest for myself.

We used to have an energetic one-hour ride. By this time Sunny’s walk was sluggish and her trot was plodding, and she barely gave me a short, four-beat canter. Even on cool mornings my sweaty clothes stuck to me by the time I finished my ride.

The vet assured me that she was in good health. “She’s showing her age.”

After a particularly frustrating lesson, Jackie said, “She needs to work harder than you’re working.”

The more leg pressure I exerted, the more difficult Sunny became.

When she, for the third time, bit my arm as I tightened her girth, I thought, Message sent, loud and clear! These weren’t vicious bites. She could have drawn blood. They were “I’m annoyed” bites that left marks.

All these indicators said, It’s time for Sunny to retire. Yet . . .

* * *

I started riding other horses. They provided mindfulness and escape from my mother’s problems, even if I didn’t form attachments.

During lessons Jackie hollered, “Slow down.” Something I hadn’t heard in months.

I purposefully tacked these horses up in the crossties by Sunny’s stall. Earlier she would have shown signs of distress. Who’s with my person? Instead she kept on eating, head down.

Even so, for a while I rode Sunny after each of the other horses, hoping to see improvement. If anything, she became slower.

One morning the weather was stormy with sheets of rain and some thunder. The younger horse I rode never flinched. I quit riding Sunny that day after she spooked and I took another tumble.

* * *

Every few days my mother hobbled the mile to a grocery store and bought a couple of gallons of cheap white wine.

On one of these days, a stranger came to my front door. The gray-haired woman introduced herself as someone who lived near my mother. “I picked her up, carrying a big bag. She was about to enter the woods in back of our houses. It’s a shortcut. I was afraid she’d get lost.” The woman hesitated, as if wondering how much to say. “She shouldn’t be living alone. I’ve picked her up other times when she’s been disoriented and walking the wrong way.”

“She refuses to move from her house or have anyone come in to help her.”

“Some older people are like that.” The woman didn’t mention Mom’s drinking.

Later I said to my mother, “What if you’d disappeared for days out there?”

“I would have found my way.” She stuck her chin out.

It reminded me of the old man who lived in a deserted lodge on Mount St. Helen’s. Also an alcoholic, he refused to leave in spite of numerous warnings that it would soon erupt. When the volcano exploded, lava and ash buried him.

Still, he lived and died on his own terms.

* * *

Jackie and I moved Sunny to a barn that specialized in retired horses. Kids came to groom her and learn simple horse care. I kept her blankets clean and brought an apple on each visit. She always nickered and nuzzled up to me. At first she grew heavier and her coat lost its shine, but she seemed happy. There was always someone to hand-walk her and give her attention.

“We love her. She’s the best,” the kids said.

I didn’t know how long Sunny would live, but her life couldn’t have been better, and she gave me consolation following my mother’s death.

At last Mom got her wish. We found her on the living room sofa with an empty wine bottle nearby. The mortuary people covered her body bag in a patchwork quilt similar to the ones she used to make and carried her out of the house—feet first.

My family and I stood next to the walkway—heads bowed.

__________________________________

Kathleen Glassburn resides in Edmonds, Washington with her husband, three dogs, two cats, and a 50-year-old turtle. When not writing or reading, she likes to play the piano and horseback ride.

Her work has been published or is forthcoming in Academy of the Heart and Mind, Adelaide Literary Journal, Amarillo Bay, Belle Ombre, Blue Lake Review, Broad River Review, and many other journals.

She is Managing Editor of The Writer’s Workshop Review. Her novel, Making It Work, and new short story collection, Where Do Stories Come From?, are now both available. For more information, please see kathleenglassburn.com

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link