by Ralph Berry (August 2020)

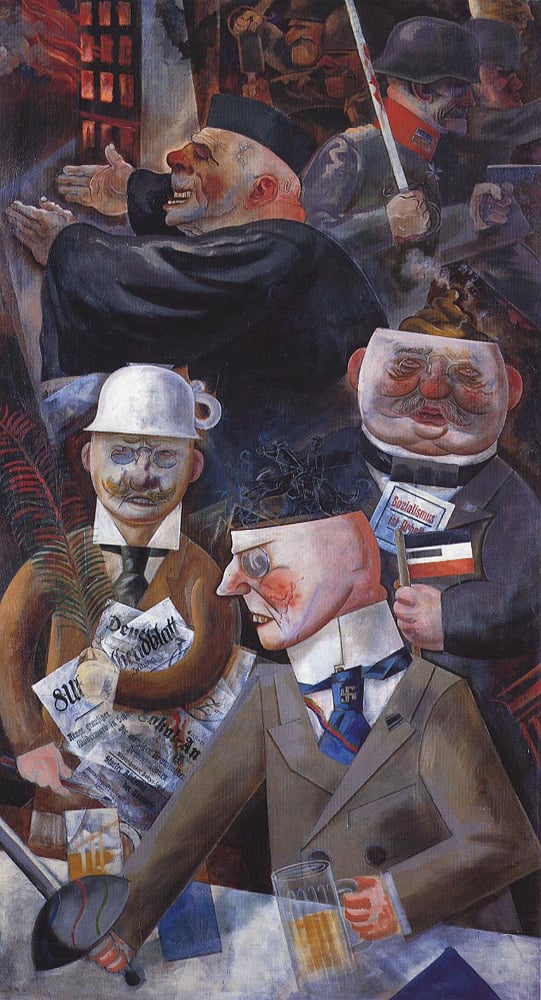

The Pillars of Society, George Grosz, 1926

Hitler was no Shakespearean. His only known reference came on the evening of 4 February 1942, when Hitler was entertaining Himmler at the Berghof and the conversation got round to Shakespeare. He was probably referring to Hamlet and King Lear when he said that it was a

misfortune that none of our great writers took his subject from German Imperial history. Our Schiller found nothing better to do than to glorify a Swiss crossbowman! The English, for their part, had a Shakespeare, but the history of his country has supplied Shakespeare, as far as heroes are concerned, only with imbeciles and madmen. —Andrew Roberts, The Storm of War, p. 608, quoting from Trevor-Roper’s Hitler’s Table Talk

From which it is clear that Hitler was no acute or attentive student of Shakespeare. Even so, Unser Shakespeare remained a top Aryan. Goering had visited Kronborg Castle, Helsingor (Elsinore) in August 1938 for Hamlet performed by a German actor. It was sandwiched between Laurence Olivier’s Hamlet in Kronborg (1937) and John Gielgud’s Hamlet there (1939). Shakespeare had given Hitler, if he knew it, the template for his own rise to power. Richard III stands apart from the other history plays, and indeed from English history. Henry VIII can only be rooted in the life of that monarch, and on stage he can only be portrayed in the costume that Holbein painted him in. Henry V leads up to the specifically English–or rather, British–victory of Agincourt. But all nations know what a tyrant looks like, for all have experienced one—or more. Richard III is the archetypal rise and downfall of a tyrant.

The broad pattern of Hitler’s life offers many Shakespearean parallels, but I want to concentrate here on a particular episode: the liquidation of Ernst Roehm, commander of the SA (Sturmabteilung) in June 1934. In it, Hitler follows, no doubt unconsciously, the method laid down in Richard’s handling of the Hastings problem. I follow the story set out in Ian Kershaw’s magisterial biography Hitler.

Roehm was the leader and Chief of Staff of a paramilitary force numbering 4 and a half million. Proclaiming total loyalty to Hitler, Roehm’s thuggish followers, the Brownshirts, had intimidated the voting public and were a great factor in the success of Hitler’s Nazi Party, the NSDAP at the polls. But they were getting out of hand, and Roehm’s ‘politics of hooliganism’ were disrupting the State. And this threatened Hitler’s own prospects in 1934, for the coming death of President Hindenburg meant the SA pretensions could lead to a Presidential successor determined by the military. So Roehm had not only to be kept on a leash, but quelled. In good time.

Now consider Richard’s position. During his own succession crisis, he was not King, but Lord Protector. The elder son of the late King Edward IV was the heir to the throne. Richard had therefore to fuse temporarily the roles of Lord Protector, which is provisional, and King, which is for life. So the young Princes and their key supporters would have to be eliminated for him to become King. In the same way, Hitler, as President Hindenburg approached his end, was not the unchallengeable ruler of Germany. He was only Reich Chancellor. So he had his ministers sign a law that on Hindenburg’s death (which took place on August 2, 1934) the office of Reich President would be combined with that Reich Chancellor. The parallel is exact.

Meantime, the Roehm problem had to be dealt with. Hitler was told by Viktor Lutze, a highly-placed SA officer, of ‘treasonable remarks’ by Roehm. They were indeed. ‘Hitler has at least to be sent on leave. If not with, then we’ll manage the thing without Hitler.’ This corresponds to Hastings and his frank avowal of loyalty:

But that I’ll give my voice on Richard’s side, To bar my master’s heirs in true descent, God knows I will not do it, to the death. (3.2.52-4)

Catesby, the Lutze figure, reports this back to Richard, and the die is cast. Lord Hastings must go. Similarly, Hitler had decided to make his move against Roehm. First, he instigated inquiries through the security services of the SS (Schutzstaffel). They worked overtime to concoct alarmist reports of an imminent SA putsch. ‘An SA putsch was now thought likely in summer or autumn.’ The stage was now set.

Hitler summoned the SA leaders to a conference in Bad Wiessee (call it ‘a separated Council,’ as in Richard III, 3.2; the real Council had taken place in Berlin). Enraged by reports of SA disturbances there, he flew down to Munich and arrived there as dawn was breaking.

Hastings: What is’t o’clock?

Messenger: Upon the stroke of four.

That was Hastings’s last chance to take flight. Roehm had no such chance. Hitler with his entourage pulled up at 6.30 am outside the Hotel Hanselbauer, where Roehm and other SA leaders were sleeping off an evening’s drinking. Hitler, followed by members of his entourage and a number of policemen, stormed up to Roehm’s room and, pistol in hand, denounced him as a traitor. He was placed under immediate arrest. On July 1st, he was told to take his own life and given a pistol. After ten minutes, no shot had been heard, and the two official executioners, Eicke, Commandant of Dachau, and his deputy, Lippert, re-entered the cell and shot him dead. A month later Hindenburg died, and the way was clear for the ‘coronation’ of Hitler.

All this follows the plot-line laid down in Richard III. The Council scene (3.4), which is formally about Coronation arrangements, pre-figures Hitler’s tactics. The scene begins with Richard, all smiles, coming late to the meeting—the Chairman often does—and then making an excuse to leave the room. He is briefed by Buckingham on Catesby’s report, and returns with a terrible denunciation: ‘Thou art a traitor! Off with his head.’ And his aides carry out his orders. Again, just two suffice, Ratcliffe and Lovell.

That is not the end of the matter, for the public has to be squared. Richard and Buckingham put on a show for the Lord Mayor, the representative opinion-former. He is told that there was a Security Alert! A Plot to murder Richard and Buckingham! Hastings was the ring-leader! Fortunately the Plot was discovered in time by the ever-vigilant security forces, and the villain put to death! Sometimes the security people do act precipitately, through an excess of zeal. But was not this action culpable?

No, for ‘the extreme peril of the case,/The peace of England, and our persons’ safety/Enforced us to this execution.’ Hitler used a nautical image to justify the event:

he likened his actions to those of the captain of a ship putting down a mutiny, where immediate action to smash a revolt was necessary, and a formal trial was impossible. He asked the cabinet to accept the draft law for the Emergency Defence of the State (pp. 313-14)

The method is universal. There is actually a filmed record of Saddam Hussein being challenged in a council meeting, ordering the miscreant out of the room where he was immediately executed, off-stage.

More remained to be done, after the killings (some twenty of the SA leaders were executed right away; they corresponded to the earlier executions of Rivers, Grey and Vaughan). The smear campaign was used to vilify posthumously the plotters of the putsch (which did not exist). Sex did the job. Roehm was a notorious homosexual, as were a number of his fellows. Heines, the Breslau SA leader, had taken large advantage of his conference opportunities and was found in bed with a young man—a scene that Goebbels’s propaganda later made much of to heap moral opprobrium on the SA.’

It is all in Shakespeare. The sex smear covered ‘that harlot, strumpet Shore,’ mistress of the late King Edward, and then of Hastings. ‘I never look’d for better at his hands, After he once fell in with Mistress Shore,’ says Buckingham sadly, that Goebbels-like figure and guardian of middle-class morality. Jane Shore was open evidence of Hastings’s ‘apparent open guilt . . . I mean, his conversation with Shore’s wife!’ The sheer chutzpah is breathtaking. The public meeting with the Citizens had to be fixed—there were doubters—but the resourceful Buckingham pulled off his PR coup with the focus group. It still works, this one. The coronation of Richard went ahead, without the young Princes.

In sum, Shakespeare’s plot-line is the pattern for Hitler. Just as Richard III is a two-part structure, so is Hitler’s career. In the full version of Kershaw’s epic biography, the first volume is titled Hubris, and the second volume Nemesis. The two lives are extraordinarily parallel. But Hitler’s body will not be re-interred.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

__________________________________

Ralph Berry has spent his career in Canadian universities, ending with the University of Ottawa. After that he took a Visiting Professorship in Kuwait University, followed by the University of Malaya. In recent years he has written for Chronicles magazine. His hinterland is Shakespeare, but not as a figure of Tudor history. Shakespeare for him is a mirror to today’s issues and themes, through whom we can reach at the politics of today.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast