by Brandon J. Weichert (October 2018)

Wir Daheim, Georg Baselitz, 1996

For many, the 1970s was a sad and dreary decade—the culmination of the failures and excesses of the previous two decades that came before it. If the 1960s was America’s high, then the 1970s were America’s  hangover. Yet, unfortunately, the 1970s made—or rather, unmade—the modern United States. While there were undoubtedly some great things that happened during this period, by-and-large, the 1970s destroyed the United States that was and replaced it with an irrevocably divided country (that was balkanizing itself even more) and helped to usher in a far more dangerous and chaotic world than the one that preceded it.

hangover. Yet, unfortunately, the 1970s made—or rather, unmade—the modern United States. While there were undoubtedly some great things that happened during this period, by-and-large, the 1970s destroyed the United States that was and replaced it with an irrevocably divided country (that was balkanizing itself even more) and helped to usher in a far more dangerous and chaotic world than the one that preceded it.

This pattern did not just occur in the United States, but throughout the world. It reordered our society in such ways that are only now, 40 years thereafter, beginning to be understood.

A Brief Prologue

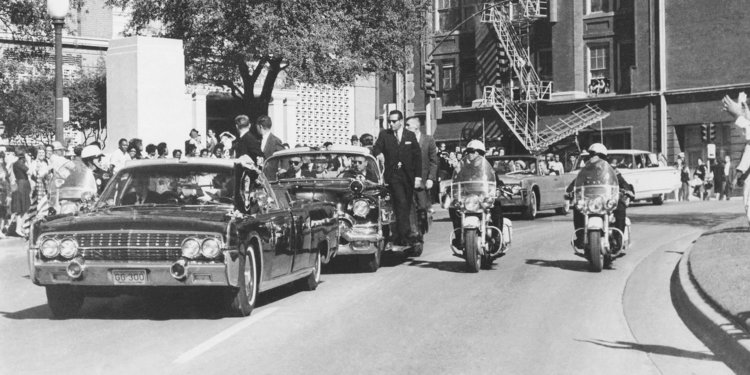

One cannot fully comprehend the doldrums of the 1970s unless it is properly contextualized in the manic changes that ripped the United States apart in the decade that preceded it. As James Piereson argues in his book, The Shattered Consensus: The Rise and Decline of America’s Postwar Political Order, the assassination of President John F. Kennedy was one of the most profoundly disruptive events for the  United States during that period. While President Kennedy was assassinated by a committed Communist, Lee Harvey Oswald, the country was told that Kennedy’s struggle for civil rights resulted in his death.

United States during that period. While President Kennedy was assassinated by a committed Communist, Lee Harvey Oswald, the country was told that Kennedy’s struggle for civil rights resulted in his death.

Just as with gun violence today, following the JFK assassination, the media blamed America’s gun culture and the Republican Party for the killing. Thus, the tragedy was converted—however unwittingly—into the biggest (improper) navel gaze in the history of the United States. Here was the birth of the self-loathing and endless moral preening that has since become the primary modus vivendi of the American Left began.

The bitter harvest planted in America’s culture, beginning with the murder of JFK—and fertilized by the chaos of the Vietnam War protests, the counterculture, as well as the development of new, incredible technologies in the 1960s—would not be fully harvested until a decade thereafter. From Kennedy’s death, though, everything was challenged.

The most important challenge of the 1960s was the Left’s major assault on traditional Judeo-Christian values. These values underpinned Western civilization generally, and specifically, American culture. Unsurprisingly, the uncertainty of the 1960s—coupled with the decreasing popularity of traditional religious mores—caused religious attendance to drastically decrease. I believe the Left’s effective challenge to these traditional Western religious and cultural values set the table for the unmooring of America (and the West) that eventuated in the bleak 1970s.

While not all people in the West were Christians, much of Western civilization had been influenced by the Christian faith. In the 1960s, the concerted attack upon that faith allowed for a more consistent assault to be conducted against many more long-held assumptions. Once religion was held in question, everything else could be challenged—and was, in short order.

The Silicon Revolution

Most people view the advent of silicon-based computing technology as a great boon for humanity. In a vacuum, the birth of the so-called “Information Age” was undoubtedly good for humanity. Unfortunately, the move into the information age did not happen in an isolated way. It impacted—disrupted, to use a favorite word today—the country (and Western society) in very serious ways.

It was during this period that the Intel Corporation’s processing chips became a ubiquitous component in American life. Meanwhile, Steve Jobs and Bill Gates both started to rise to early prominence in the 1970s—utterly disrupting the economy at the time, and creating an entirely new, all-important market that is a key driver of America’s economy today.

It was during this period that the Intel Corporation’s processing chips became a ubiquitous component in American life. Meanwhile, Steve Jobs and Bill Gates both started to rise to early prominence in the 1970s—utterly disrupting the economy at the time, and creating an entirely new, all-important market that is a key driver of America’s economy today.

While this technological progress not only led to the creation of the personal computer, it also precipitated the rapid decline in living standards, as well as stratification between the poor and rich, that everyone from Thomas Piketty to Rand Paul speaks of today. At present, only a small percentage of the American population financially benefits from jobs provided by this all-important sector.

It’s true that many more Americans benefit on the consumption side of the technology sector than on the production side. Unfortunately—no matter what many economists may say—an individual cannot be sustained by consumption alone. They must have gainful employment in order to consume products. Given the massive wealth stratification in Silicon Valley itself, it should be clear that this technological revolution was not the egalitarian event that so many technologists of yesteryear had hoped. This is doubly more evident in the fact that tech leaders, like Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk, have been calling for “universal basic income” to help those many Americans whose jobs either have been, or are about to be, replaced by technology.

The military also got in on this technological revolution. During this period, despite our stunning defeat in the Vietnam War, the U.S. military embraced the concepts undergirding fourth-generation, network-centric warfare. The digital revolution was coming to the Pentagon in the form of what became known as the Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA). This was coupled with the Nixon Administration’s decision to convert the U.S. Armed Forces from a mixed force of some volunteers and many civilian conscripts into an All-Volunteer Force (AVF).

After the chaos of the Vietnam War, the U.S. military—particularly the Army—was broken and was rebuilt from the bottom-up. The new computer technology was embraced, as a means of enhancing American combat capabilities. Things like precision-guided munitions, as well as satellite communications and imagery were defining features of the new military. Because the new American military was an AVF, it was going to need to operate with smaller numbers of troops. So, the RMA played heavily into increasing the lethality and speed of the smaller amount of troops.

The fruits of these reforms and revolutions in technology are visible in all aspects of American life today.

Economic Disruptions

The 1970s was the period in which the idea of a post-industrial “Knowledge-Based” economy came about. Under this belief, old, “dirty,” (mostly manufacturing) jobs would be replaced by jobs based on “information, technology, and learning,” according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Meanwhile, Agency Theory—the basis of what would become known as “Shareholder Capitalism”—was injected into the minds of America’s major business leaders. By the 1970s, this was the dominant theory undergirding most major business transactions. Shareholder Capitalism subordinated all interests of a corporation to what was in the best interests of a company’s shareholders. In turn, corporate CEOs became only concerned about their quarterly profits, as they were often paid exorbitantly for bringing their shareholders increasing profits at the end of each quarter.

Operating in tandem with the rise of the Silicon Dominion and Shareholder Capitalism, was the advent of the Salomon Brothers’ all-powerful “mortgage-backed securities” (MBS). These little gems were the basis of the 2008 market crash and subsequent Great Recession. They made the companies which traded in these products very wealthy, but they ultimately undermined the financial security of the American people by the 2000s.

As Selena Zito outlines in her magnum opus, The Great Revolt: Inside the Populist Coalition Reshaping American Politics, while American elites embraced a post-industrialized economy with a more globally-minded outlook, there was concomitant—and shockingly rapid—de-industrialization of the American heartland. What’s more, large corporations, began forming their “government relations” arms in Washington, D.C. These government relations departments would help to create powerful blocs of interests to lobby a pliant Congress into enacting legislation that would benefit the large corporations.

Thus, the combination of de-industrialization, the financialization of the economy, the explosion of the information age, and the rise of major lobbying in Washington, D.C. all led to the flattening of wages for most Americans. As George Packer argued in a 2013 article, “Banking and technology, concentrated on the coasts, turned into the engines of wealth, replacing the world of stuff with the world of bits, but without creating broad prosperity, while the heartland was hollowed out.”

The Political Impact

Not only were technological changes rapidly occurring, but so too were political changes. Throughout the Western world, the excesses (and failures) of Liberalism had been laid bare in the preceding decade. And, it wasn’t just in the United States or the West. Fundamental alterations to the basic political structures of the entire world were underway.

In the United States, despite the 1960s having been dominated by Democratic Party politics, neither John F. Kennedy nor his successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, were Left-wing radicals. They were programmatic Liberals in the FDR mold. Yet, the turbulent events of the 1960s—from the JFK assassination to Vietnam to the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert F. Kennedy—morphed the Democratic Party’s base into a radical, Leftist force agitating for outright revolution (rather than incremental reform).

The rise of the New Left in the 1960s was a far greater challenge to the Democratic Party than it ever was to the Republican Party or the conservatives. And, their often-violent antics in public had turned the great “silent majority” of Americans against the desires of the New Left. After the revolution never took hold in America, the revolutionaries did not abandon their ultimate goal. They simply engaged in a tactical retreat; the members of the New Left traded in their Birkenstocks for finely polished Ferragamos, and began their “long march through the institutions,” disrupting and warping American society in a slow-running, top-down, administrative coup.

As the New Left radicals went silent for a period of time, biding their time, a great conservative reaction took hold in most Western democracies. It was during this period that the Reagan Revolution began in earnest and when Thatcherism in Great Britain started to capture the hearts-and-minds.

The Conservatives of the Reagan Revolution and the Thatcherites championed individual liberty, strong foreign policy, and traditional moral values as vital antidotes to the communitarian excesses of the radical Left. Yet, even here the so-called “conservatives” fell short of their aims at truly reinvigorating and strengthening their countries. Yes, in the cases of Reagan and Thatcher, reducing taxes and increasing military spending (and exhibiting a willingness to use that force) was deeply therapeutic for their respective societies—which had been laid low by the twin evils of Leftist revolutionary politics and the dreariness of Liberal policies. However, Western Conservativism had bought into the economic theories that exacerbated the collapse of living standards and opportunities for most of the middle-class. These policies, in turn, may have benefited some. But, for the middle-class in particular, these radical changes only served to further reduce their numbers.

The Conservatives of the Reagan Revolution and the Thatcherites championed individual liberty, strong foreign policy, and traditional moral values as vital antidotes to the communitarian excesses of the radical Left. Yet, even here the so-called “conservatives” fell short of their aims at truly reinvigorating and strengthening their countries. Yes, in the cases of Reagan and Thatcher, reducing taxes and increasing military spending (and exhibiting a willingness to use that force) was deeply therapeutic for their respective societies—which had been laid low by the twin evils of Leftist revolutionary politics and the dreariness of Liberal policies. However, Western Conservativism had bought into the economic theories that exacerbated the collapse of living standards and opportunities for most of the middle-class. These policies, in turn, may have benefited some. But, for the middle-class in particular, these radical changes only served to further reduce their numbers.

The Culture Wars, Defined

If the 1960s saw the initial drawings of the cultural battle lines in today’s society, then the 1970s was the further definition of the battle space in the ongoing Culture Wars. The 1973 Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision, which set the precedent for legalizing abortion, was the most prominent example of this. Of course, there were other drastic cultural changes.

After the passage of Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society programs in 1964, a vast welfare state was birthed (on top of the one created by FDR with his New Deal programs). As Thomas Sowell illustrates, along with the expansion of the welfare state came the rise of fatherlessness—particularly in the African-American community—which remains a defining feature in American life (and contributed to poverty).

Speaking about fatherlessness in the African-American community, according to Thomas Sowell:

In 1960, which would be almost 100 years after the end of slavery, 22 percent of black kids grew up in homes with only one parent. 30 years later, after the Liberal welfare state, that number had more than tripled […] That was not due to the legacy of slavery. That was due to the legacy [of the welfare state].

Compounding all of this was the 1969 California law which created “No-Fault Divorce.” This removed the traditional cultural antipathy toward divorce and led to a major decline in healthy marriages. By the 1970s, No-Fault Divorces were all the rage.

During this period, radical feminism was in full swing (which empowered the supporters of the Roe decision and supported No-Fault Divorce). The advent of contraception had drastically changed not just male-female relations (women, like men, could now have sexual relations with the reduced risk of pregnancy), but it had also irrevocably altered the way families were formed: it effectively de-nuclearized the nuclear family by blurring the roles of husband and wife.

Reverberations of these decisions would be experienced for decades to come. As the notorious feminist, Hanna Rosin, argues in her 2012 work, The End of Men: And the Rise of Women, the feminist revolution of the last 50 years has effectively erased the role of men in our society today. Today, more women are graduating from college and finding gainful employment than their male counterparts. Divorce remains at an unfortunately high level. Of the families that are forming, American fertility rates are depressed (though, blessedly, they are not nearly as bad as the rest of the West—this is thanks largely to the traditionally higher fertility rates of immigrants, as well as the higher fertility of families in the rural United States).

Reacting to all of this came the rise of the religious Right, which overwhelmingly voted for Richard Nixon. This same group, which came to be known as the “Moral Majority,” would be instrumental to Ronald Reagan’s success in the 1980s. The 1973 abortion decision only hardened their resolve to take their country back.

In fact, the first major attacks on the traditional family began during the ‘70s, creating a positive feedback loop that furthered the rise of the Conservative Movement. The ceaseless divisions between the Left and Right had highly damaging effects for the unity—and politics—of the country, most of which remain today.

Mideast Mania

More importantly, America’s unhealthy obsession with what Andrew J. Bacevich refers to as the, “Greater Middle East” began during this period. Beginning with the infamous oil embargoes of the United States by the mostly-Arab members of the oil-producing cartel, known as The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in 1973 (ostensibly over America’s unceasing support for Israel), the United States came to believe that it needed uninterrupted access to Mideast oil. During his time in the Carter Administration, a young Paul Wolfowitz wrote the Limited Guidance Strategy for the Pentagon in which he outlined his belief that the United States needed to be willing to use its military to ensure the free flow of oil from the wider region.

Several prominent neoconservatives, such as Irving Kristol and Edward N. Luttwak (writing under a pseudonym at the time) concurred. When the Soviets invaded Afghanistan in 1979 and the Iranian Revolution overthrew the pro-American Shah in Iran (replacing with him with a radical, Shiite Muslim theocracy), the Carter Administration agreed with the hawks. The Carter Doctrine was birthed from these tumultuous days. President Jimmy Carter’s vow to use any-and-all means necessary to ensure the stable, free flow of oil out of the Mideast set the stage for America’s increasing involvement in the Mideast since the 1990s.

Meanwhile, the specter of radical Islam hung over the region.

It was in the 1970s that Islamist movements, came to the fore. The Muslim Brotherhood would create such violence and vituperation in Egypt that one of its members would eventually assassinate President Anwar al-Sadat in 1981, in an attempt to prevent Egypt from making peace with Israel. But, the immediate origins for that heinous act can be found in the instability of Egyptian politics throughout the 1970s.

In this era, the unstable, though somewhat democratic regime of Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was overthrown in a bloody, military coup in Pakistan. The man who replaced (and assassinated Prime Minister Bhutto), Zia-ul Haq, was not only a general in the Pakistani Army, but he was also a committed Islamist. During this period, Pakistani Colonel S.K. Malik wrote, The Quranic Concept of War, a treatise on Islamic warfare doctrine in the modern world that became required reading among the Pakistan military. Malik is viewed as the Pakistani Carl von Clausewitz.

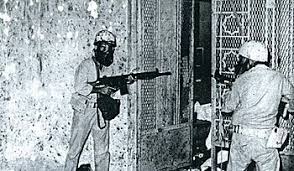

Further, the rise of Islamic extremism not only afflicted Pakistan in South Asia or the predominantly Shiite Iran, but it also swept over the majority Sunni Arab world in the form of the Grand Mosque seizure in 1979. During this event, elements of a radical Islamic sect, known as Wahhabism, took over Grand Mosque at Mecca and laid siege to it for weeks—insisting that the royal Saudi family abdicate and place True Believers in power (and evict the infidels they had aligned with). These Wahhabis were the direct precursors to Osama Bin Laden and al Qaeda.

Further, the rise of Islamic extremism not only afflicted Pakistan in South Asia or the predominantly Shiite Iran, but it also swept over the majority Sunni Arab world in the form of the Grand Mosque seizure in 1979. During this event, elements of a radical Islamic sect, known as Wahhabism, took over Grand Mosque at Mecca and laid siege to it for weeks—insisting that the royal Saudi family abdicate and place True Believers in power (and evict the infidels they had aligned with). These Wahhabis were the direct precursors to Osama Bin Laden and al Qaeda.

While the siege of Mecca ended in a bloodbath which saw most of the Wahhabis wiped out by a team of French commandos, the seeds for a violent, Islamic revival had been planted in the entire region—and fertilized by the blood of believers and so-called kuffar alike. Today, the growth of Islamism is in full bloom.

Asia Ascendant

The 1970s was also the period in which the United States and the People’s Republic of China became partners against the Soviet Union. While the move toward peace between Beijing and Washington, D.C. was an essential element in America’s ultimate victory over the Soviet Union in the Cold War, it was also the death knell for America’s global dominance.

Even former President Richard M. Nixon recognized the perils of blindly opening up the United States to China (many claim Nixon opened up China to the world. In fact, the process was begun by Mao Zedong and Nixon seized the moment to bring the world to China, not the other way around, unfortunately). When President Jimmy Carter endorsed the asinine “One-China Policy” which challenged Taiwan’s claims to legitimate sovereignty, Nixon was apoplectic.

Even former President Richard M. Nixon recognized the perils of blindly opening up the United States to China (many claim Nixon opened up China to the world. In fact, the process was begun by Mao Zedong and Nixon seized the moment to bring the world to China, not the other way around, unfortunately). When President Jimmy Carter endorsed the asinine “One-China Policy” which challenged Taiwan’s claims to legitimate sovereignty, Nixon was apoplectic.

While Nixon had shrewdly taken Mao’s opening, he never once intended to bring the United States fully over to China’s side when it came to the Sino-Taiwan dispute—not without having extracted considerable concessions from Beijing. Carter, on the other hand, had merely embraced the Chinese view without adequately setting parameters for such a major policy shift. Thanks to the Carter Shanghai Communique, which recognized the One-China Policy, the United States had lost one of its strongest elements of leverage over the Chinese.

Shortly thereafter, in combination with the aforementioned de-industrialization push in the United States, the country’s leading executives began pouring resources and funds into China’s burgeoning economic development. At precisely the same time American politicians and business leaders were killing the American middle-class by allowing the entry into the American economy of cheap Chinese goods, the Chinese middle-class was built up at the expense of Americans.

The money and knowledge that these policies conferred upon China rapidly translated not just into economic might but also significantly aided in China’s rapid rise to global military power.

On the Road to Ruin

From oil embargoes to the decline of the African-American family; from the first formations of the Islamist threat faced by the world today to Culture Wars that continue dividing us, the 1970s was one of the most transformative decades of the modern era. It was also one of the most ruinous—with its impact still being felt today.

The politics of America and the world today are more a reflection of the unfinished business began during this period than anything else. The 1970s unmade the United States (and, ultimately, the world). The last 38 years have been about trying to repair the damage. The next few years will determine how effective the repairs have been.

Going forward, the United States needs to recognize that the “energy crisis” of the 70s never really ended. In fact, America’s involvement in the Mideast and its dealings with both China and Russia, have largely focused on the competition for greater access to energy. The Trump Administration’s decision to fully allow for the development of American energy resources is a great step to mitigating some of the more destructive aspects of American foreign policy since the 1970s. However, that is a short-term fix. Trump and future presidents of both parties simply must invest in nuclear power; the president should embark upon a great expansion of America’s energy infrastructure; and federal research and development should go into realizing nuclear fusion.

From there, the United States must be more willing to protect its critical industries from foreign attack. Not all free trade is good, and American leaders must strenuously protect the country from bad deals. The creation of a thriving, easily-accessible middle class helped to make the United States into the superpower that it is today. The systematic withering of that middle class is directly responsible for the slow, relative decline of the United States. Therefore, any policies—regardless of whether they belong to the Democratic or Republican political playbooks—that protect and expand America’s ailing middle-class must be embraced.

From a values perspective, American culture must be defended from the excesses of the 1970s. Things like abortion should be challenged; our children should be taught from the earliest age to respect the customs and traditions of our forefathers; and a full-on restoration of America’s Judeo-Christian heritage must begin now. The damage of the 1970s is deep and will take more than one presidency to repair. But, the Trump presidency is the last, best chance to stop the erasure of traditional America.

A Slight Epilogue

As you can see, the selection of the 1970s as being the most destructive for the world was not a random choice. While the 1960s were certainly disruptive, that decade must be viewed in greater context of the succeeding three decades. You see, the 1960s began the revolution. But, the 1970s leveled American society to such a point that it made the inevitable, long-term decline of the United States all the more likely.

The 70s, as I elucidated above, also saw the coming of a serious counter to the Leftist revolution that the 1960s begat. Yet, unfortunately, that conservative reaction was fleeting at best. It would be easy to say that the 1980s was the antidote to the mania of the 60s and the destruction of the 1970s. Unfortunately, though, that was not the case. In fact, the major trends that started bearing poisonous fruit in the 1970s continued maturing in the 80s—and in many cases, it was the so-called Conservatives who perpetuated the negative trends.

While the Reagan tax cuts helped to goose the economy, the deficit spending activated a slow-ticking debt bomb that still threatens the American people today. And, the manic obsession with the Greater Middle East that plagues American foreign policy today was around then. In fact, elements of the failures of American Mideast foreign policy today can be found in the American involvement in the Soviet-Afghan War; the Iran-Iraq War; and the civil conflict in Lebanon (to say nothing of the American engagement against Muammar Gaddafi’s Libya).

Shareholder capitalism defined the 1980s. Gordon Gekko, the actual villain of the hit film, Wall Street, was idolized by many as a someone to emulate. Free trade continued tearing the heart out of the United States and shipping jobs and opportunities elsewhere. Drug use was rampant (and glorified by Pop Culture). Church attendance did increase, but general skepticism around traditional culture remained in full force, not only in the United States, but throughout the West.

The so-called “conservatives” during this time, while embracing the “Moral Majority” in the United States (and similar traditional movements in Europe), mostly refused to engage in the Culture War. Everything was focused on hardline foreign policy and supply-side economic programs. Thus, the deterioration and decline of America that began in the 70s was continued in full force during the 1980s. More of the assumptions made in the 70s were maintained and built upon in the 80s. Unless a clean break is made with the patterns imposed upon the West by the 1970s, the West will continue its seemingly inexorable decline, and the United States will collapse. Time is not on America’s side, though. Decline is a choice. We must choose to reinvigorate our country and culture with due haste. After all, no one else will.

_________________________

Brandon J. Weichert is a geopolitical analyst who manages The Weichert Report: World News Done Right and is a contributor at The American Spectator, as well as a contributing editor at American Greatness. He also travels the lecture circuit, where he talks about the concepts of space warfare. Brandon is a former Congressional staffer who holds an M.A. in Statecraft and National Security Affairs from the Institute of World Politics in Washington, D.C. and is currently working on his doctorate in international relations.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

One Response