by Esmerelda Weatherwax (February 2011)

We went to the Tate Modern gallery on the Southbank a few weeks ago. I was a frequent visitor to the first Tate Gallery, now known as Tate Britain in Millbank when I worked nearby but this was the first time I had set foot in the new site in the former Bankside Power Station. The Bankside Power station is not the famous one with a chimney at each corner to which an inflatable pig was tethered for the cover of Pink Floyd’s album Animals; that is the former Battersea Power Station further upstream.

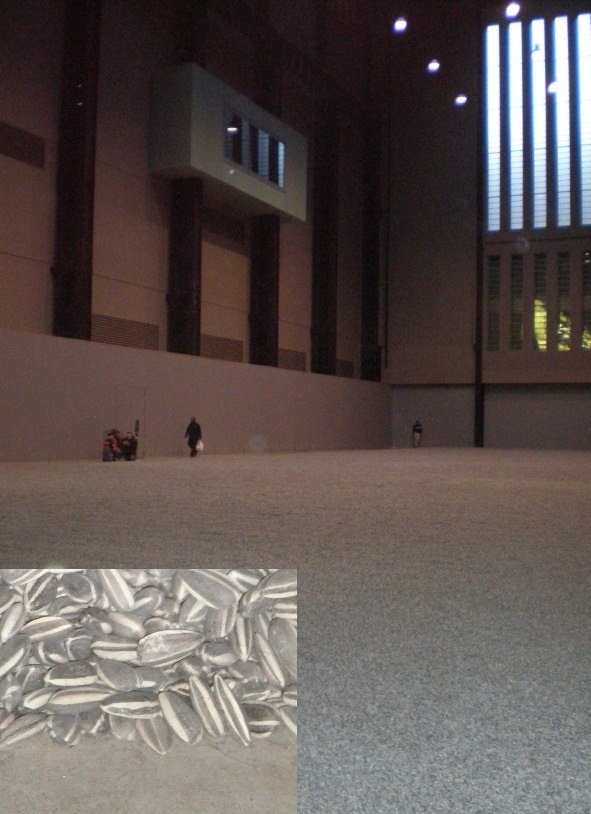

Bankside has the one central chimney and the huge internal space of the Turbine Hall (now minus the turbines) which are worth a look on their own architectural (20th Century industrial school) merits.

The big exhibition at the moment is Ai Weiwei’s Sunflower Seeds. 100 million ceramic sunflower seeds spread across the vast floor of the Turbine room. At first the visitors were allowed to walk across them, and play in them. For 48 hours the public scooped them up and trickled them through their fingers, built sandcastles and left footprints. Then the Health and Safety officers decided that with constant use particles of ceramic dust would be produced which could constitute a health hazard. The seeds were roped off to protect the public, and protect the seeds from theft. Which is how I viewed them last month.

Photograph below, the length of the Turbine Hall with detail of the seeds inset.

I was sceptical at first as to me, philistine that I am, art is the likes of Vermeer or Van Gogh, producing with their own hands skilful works of genius that no one else could have made. Works that move and inspire. Works that I, who cannot draw a straight line, could never have made.

I knew that Ai Weiwei did not make 100 million ceramic reproductions of sunflower seeds himself but commissioned their manufacture. I have heard reports of terrible conditions in many of China’s factories, stories like that of workers locked in the workshops who died when they could not escape a factory fire. So my first glance at these 100 million seeds made me think of labouring proles who are not only downtrodden but through whose cheap labour bosses are undercutting what is left of British manufacturing industry. All the seeds look the same. All the seeds are grey.

The nearby video put a different light on the installation. Sunflower seeds are a popular snack in China. Chairman Mao liked to show himself surrounded by sunflowers (bright yellow and enormously cheerful) and by implication the seeds were the adoring population of China, paying him homage. The piece is intended to provoke thought on the nature of population, China post Mao, individuality compared with conformity for the common good, and suchlike.

The seeds were manufactured in the city of Jingdezhen which has a long and illustrious history of making ceramics. The project gave over a thousand workers a living for several years. The conditions in the china clay mines didn’t look too comfortable but the rest of the process took place in small workshops all over the town. Everybody knew someone who was working on the seeds. The painting was done by women who reminded me of the paintresses described by Arnold Bennet in his stories of The Five Towns, centred on England’s ceramic industry (much of which is now outsourced to China) in Stoke and Burslem. So each one, although looking the same, was actually unique, being made by hand.

Many of the women, who were skilled and deft, worked at home, in between their household duties. My mother was an outdoor worker for a London factory when I was a child, and I used to help her, so I know all about outdoor work. Ai Weiwei talked to them as they painted. Some took six strokes of the brush to finish a seed; the most skillful could do it with three. One older woman spoke of working during Mao’s time, but that she had never been assigned to paint him on any of the pottery made to commemorate him.

I could now understand a little of what Ai Wei Wei wanted to say with his installation but I was still left wondering what value it had as art if nothing about it could be understood without his explanation.

A picture like The Census at Bethlehem by Pieter Brugel the Elder is immediately a winter scene with a lot of activity to look at. If you knew nothing else about it you can appreciate the people skating and riding horses. If you already know, as everyone who viewed it would have known until recently, that in the centre Joseph and Mary have arrived in Bethlehem and are about to find that there is no room at the inn the level of understanding is immediately deeper. It deepens still further to know from the history of the artist that the town meant to be Bethlehem under Roman occupation is actually Holland suffering under the occupation of the Hapsburg empire, and then to notice tiny details of how they lived then.

No one seeing sunflower seeds in an art exhibition could fail to be reminded of Van Gogh’s sunflowers which he painted more than once. And again, they stand alone as beautiful flowers, but enhanced if you know that while he painted such cheerful beauty Vincent was frequently a tormented and unhappy man.

While pondering the subjects of colour, the difference between art and craft, the demise of British manufacturing industry, and some of the other themes that exercise my mind I came up with my own small version of Sunflower Seeds.

I like colour and I sew and knit, at the level of craft not art. I would submit that embroidery and weaving can produce art to rank with painting, like the Bayeux tapestry or the tapestry of Christ the King in Coventry cathedral. There are still factories in England manufacturing buttons and I have a button box. I also have a digital camera and I’m not afraid to use it.

So I present Weatherwax’s British Button Box.

As you can see they are all shades and colours.

Buttons from macs and buttons from slacks.

Buttons off shirts and buttons off skirts.

Some are purely functional; others designed to be decorative as well. They are plastic, shell, mother of pearl, wood, metal, covered in silk or velvet, round, long, and shaped like animals. Across them all flows a rainbow string, representing either secular ‘diversity’ or God’s promise made to us after The Flood. All different, but all created to fasten or embellish our clothing.

Some are purely functional; others designed to be decorative as well. They are plastic, shell, mother of pearl, wood, metal, covered in silk or velvet, round, long, and shaped like animals. Across them all flows a rainbow string, representing either secular ‘diversity’ or God’s promise made to us after The Flood. All different, but all created to fasten or embellish our clothing.

If any arty billionaire wants to give British manufacturing a boost by commissioning this at a size to fill the Turbine Hall next year I can be contacted via the NER home page.

Left is a photograph of a London Pearly King. They were originally families of costermongers who decorated their suits with rows of mother of pearl buttons. The idea has spread out of London and out of the vegetable trade and these days the Pearlies main activity is charity work. The Pearly King of Upminster was helping fundraise for an Essex hospice that day. Do foreign museums examine with interest the folk art of the Cockney artisan?

As I left the Tate Modern I stepped across what had been Doris Salcedo's crack, about which my colleagues Hugh and Mary commented here and here. It has been filled in very neatly, in a fine example of the maintenance team’s craft. I didn’t photograph it; even a nerd has her limits.

Today (28th Jan) comes the news that there is another health concern around the seeds. The paint used may contain lead. While this is unlikely to be a danger to visitors to The Tate it could be a concern for all those paintresses in Jingdezhen who practised their craft so diligently.

To comment on this article, please click here.

If you enjoyed this piece and would like to read more by Esmerelda Weatherwax, please click here.

To help New English Review continue to publish articles such as this one, please click here.

Esmerelda Weatherwax is a regular contributor to the Iconoclast, our community blog. To view her entries please click here.