By John Broening (July 2021)

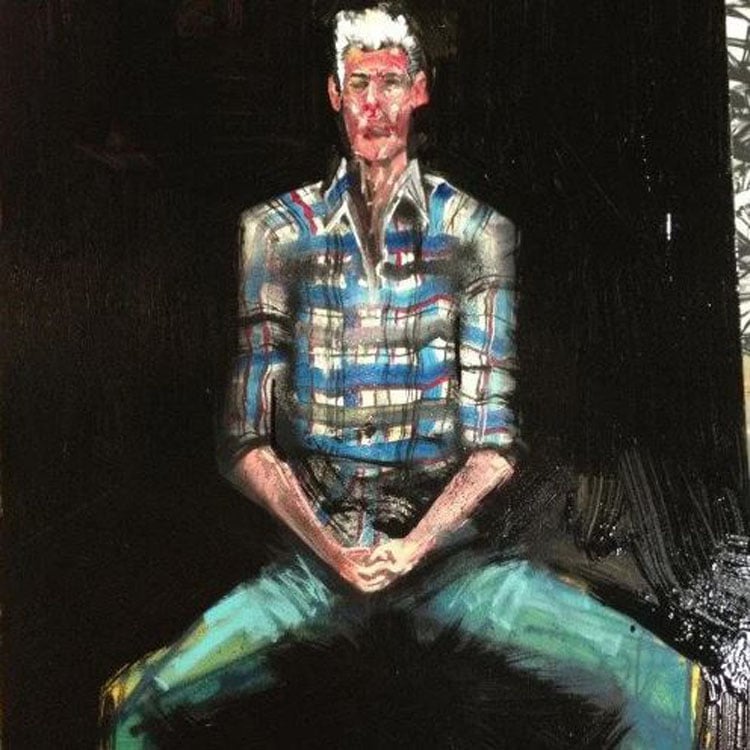

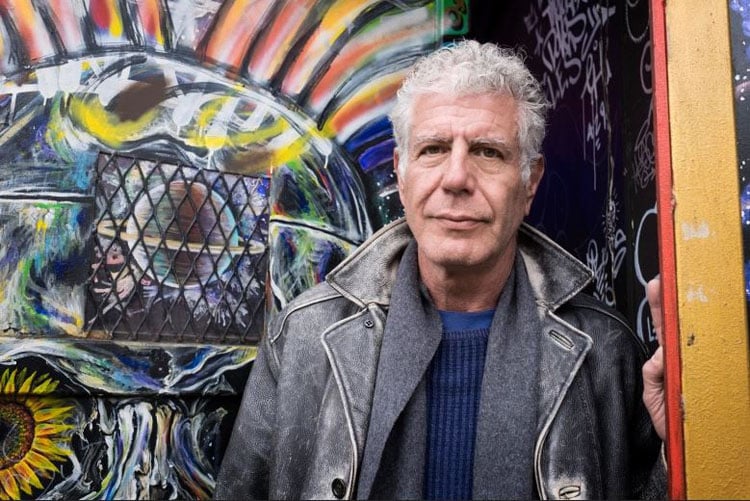

Anthony Bourdain, by David Choe

About a month after Anthony Bourdain hanged himself in a hotel room in France, I found myself at a party talking to two people who, like me, were in the food business. It transpired that all three of us had some connection to the late chef, writer, entrepreneur, and TV personality. I knew that one of the guests, a biker-turned-repo-man-turned-hot-dog-stand-operator, had been featured on a segment of Bourdain’s travel/food show, No Reservations. Bourdain’s touch, like Oprah’s, changed lives, made fortunes and reconfigured the culture. After that segment aired, the hot dog stand had grown into several restaurants and a stadium concession. With all this, for the biker, came a whole new set of headaches—he seemed to yearn for the simpler days when he was his only employee.

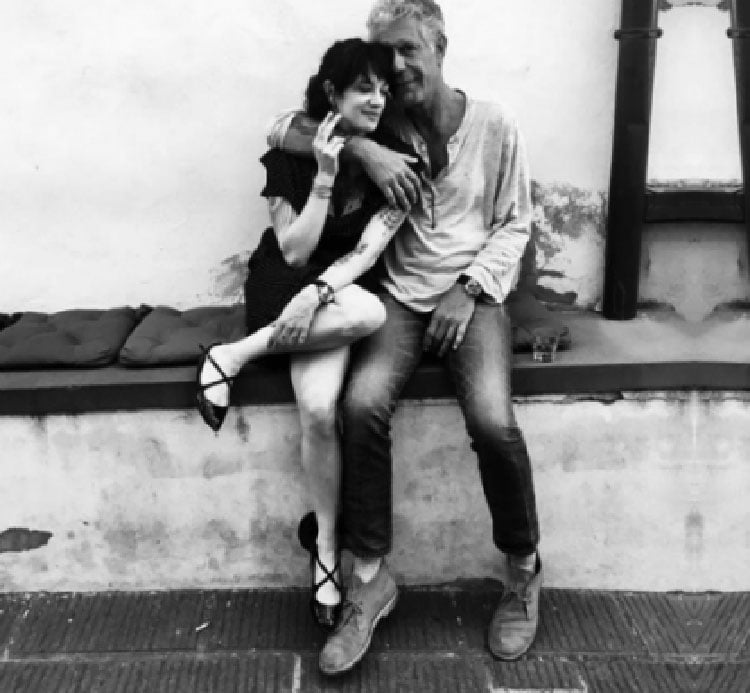

The other guest, a restaurant publicist, had met Bourdain after one of his wildly popular speaking tours (made up of what he called “war stories and dick jokes”). After she met him, she had, for a little while, posted on her Facebook page a shot of herself in his arms: her face is radiant with ecstatic embarrassment; he is smiling unguardedly, happy to make her happy. After his death, the photo was back up on her Facebook page.

We were all three of us still deeply shaken by his suicide, and puzzled why someone who was not only successful, and—we assumed very rich, but also universally beloved—why someone whose every thought and published word was pored over; whose every joke was laughed at; who had his own publishing imprint, a food hall in the works, a series dedicated to the creative processes of chefs, a line of comic books, a line of curated goods; who hosted a popular television show which gave him complete creative freedom to travel around the world, say what he wants, hang out with his cultural heroes and eat the best food there was—why had he killed himself and left behind a young daughter as well?

You couldn’t point to the usual reasons offered for the suicide of artists: a decline in the quality of their work and writer’s block (Hemingway, Brautigan), physical inability to practice their art (Keith Emerson), or a lack of recognition (Van Gogh, John Kennedy Toole).

Bourdain seemed at the time of his suicide to be at the absolute peak of his powers and had become, like Dave Chappelle, one of those rare cultural figures who are so esteemed that they are free to color outside the lines.

Often when someone who has been part of our culture dies, their death confirms what has been a long decline in renown. There are the usual thoughtful reevaluations and heartfelt remembrances and after that the reputation and the work disappear down a memory hole. This is what happened, for example, with Norman Mailer after he died in 2007.

But Bourdain is, three years after his death, bigger than ever. There have been a number of tributes, many right after his death, and then a few on the anniversary of his suicide. There is a documentary about his life, several biographies in the works, as well as a touching collection of tributes from both celebrities and ordinary people. The tributes are of the heartfelt ‘you-changed-my-life’ variety more commonly elicited by a spiritual figure than a profane ex-junkie:

He has made me a better person-gentler, more accepting, and a thoughtful listener.

Anthony gave every guy in America who’s trapped in a dead-end job hope that life gives us second chances.

He made us [cooks] heroes to ourselves.

He was far more than just the host of a popular TV show. He was a singular force in the universe for good and for good times.

He was one of those rare figures equally mourned on both ends of the political spectrum. In National Review he was remembered as a “model of generosity and curiosity.” In The Root, their most talented and militant writer, Damon Young (“Whiteness is a Pandemic”), wrote:

He was a rich and powerful (and white) man who used the privilege that his riches, his power, his whiteness and his maleness provided to him to shed a spotlighton those without it. He was a tourist of the world who still treated people and cultures like people and cultures and not pamphlets.

There is an Anthony Bourdain Day, an Anthony Bourdain scholarship, even an Anthony Bourdain trail. On eBay you can buy a framed setting of Bourdain’s best-known quote (“Your body is not a temple. It’s an amusement park. Enjoy the ride.”), like one of those pious samplers found in 19th century homes.

Bourdain seemed to represent the best of 21st century America, our tolerance, our openness, our bespoke attitude towards self-expression and self-fashioning, and our YOLO desire to draw the most of experience, to suck the marrow out of life.

Bourdain was also beloved because he was one of those rare celebrities with little apparent sense of entitlement. It’s hard to imagine him throwing a fit about the size of the fruit basket in his hotel room or the placement of his table at an awards banquet, except perhaps as some kind of Chris Elliott-like schtick. Bourdain seemed to do everything out of a real, rather than a performative, sense of humility. Recollections of him describe a kind of anti-Streisand, someone who would rarely say no to an interview request, who would show up for his appointments not on time but early. No one was more generous in the promotion of little-known talent, or in the writing of blurbs, an unpaid chore that requires you to boil down a two-hundred-page book to a handful of memorable words.

His story, was, he knew, one that people loved when they saw it on the screen just as they saw Stripes, Caddyshack, Happy Gilmore, My Cousin Vinny or Animal House but all-too-rare in real life. It was the story of The Triumph of the Fuckup. What Bourdain believed to be his own unbelievable good fortune accounted for both his posture of eternal gratitude and humility and a large portion of his public adoration.

One of the many tragic things about Bourdain was that this deep humility, profligate generosity, and respect for and liking of people as they are, seemed in his inner landscape to exist uncomfortably close to an inextinguishable self-hatred, and a heedlessness about self-preservation. After he signed away his prime apartment in Columbus Circle to his estranged wife, he shrugged, “I was always meant to be a renter.” He insisted that the size of his fortune was vastly overestimated because of his cavalier attitude towards money and this was borne out after his death by the shockingly small size of his estate.

Gabrielle Hamilton, the chef and writer, said after his death:

That’s the thing about friendship with Tony. Tony lavishes you with love and friendship and generosity and kindness, and then he disappears in the night and you don’t get to reciprocate. It wasn’t mutual. But it was breathtaking to be loved by him.

The heedlessness about self-preservation included a deeply-felt jemenfoutisme that underlay Bourdain’s singular approach to his chosen medium. He said:

. . . everyone on television . . . by and large, lives in fear. And what they’re afraid of is that someday they won’t be on television. So they’re not gonna try anything new, because, well, they’ll say they want something new, but what they really mean is the same thing that worked last year . . . Which is exactly the opposite of what interests me, which is to never repeat what I did last week, whether people liked it or not. But I’m kind of a freak in the business, in that a) I’m not interested in doing the same thing, even if it worked, and b) you know, it wouldn’t be the worst thing in the world to not be on television anymore.

I’ve done just enough food television—mostly segments on local morning shows—to appreciate the difficulty and uniqueness of what Bourdain accomplished. The high point of my brief television career was following Deepak Chopra on an ABC affiliate talk show.

I chatted with Chopra beforehand, but was too mesmerized by his jewel-encrusted wristwatch to say much, or to remember anything he said. I observed him do his thing on camera: Utterly relaxed and cashmere-smooth, he was self-deprecating (“I’m a prophet. P-R-O-F-I-T’’); he was funny (“If Oprah and I had a child, it would be called Oprah Chopra’’); he was quick on his feet (asked to give the secret to happiness in 20 seconds, he said “Avoid toxicity: Toxic substances. Toxic emotions. Toxic situations.’’) But it was still the same—albeit Indian-flavored—combination of Laws of Attraction with Gospel of Success that you saw everywhere on television in those days.

After I watched the man singlehandedly responsible for Demi Moore’s spiritual renewal float out of the studio, I set up to do my bit, something for Colorado Lamb Month. I executed my stand-and-stir segment, sprinkled in my rehearsed bonmots, and finished as the cameraman cued for a commercial. I had gotten skillful enough to snuggly fit my seven-minute segments into their seven-minute slots. But it never occurred to me to do anything different from what I’d seen other chefs do on TV, because my ambition was nothing greater than to not screw up so I would get invited back.

Bourdain, by contrast, could bend the medium to his will not just because he didn’t give a fuck, but because his powerful dream of what food television could be originated from outside food television. His work was so singular because it wasn’t inspired by Bobby Flay or Martha Stewart. It was inspired by Hendrix shredding Star Spangled Banner at Woodstock, and by Rebecca West in the Balkans and Coppola in Vietnam.

This meant that, until he found a safe home at CNN, his career in TV resembled a cartoon character frantically ascending a ladder as its lower rungs disintegrate beneath his feet.

In Medium Raw, Bourdain describes his final meeting at the Food Network with Brooke Johnson, for decades the most powerful executive in food television:

Ms. Johnson was clearly not delighted to meet me or my partners

. . . There was a limp handshake, as cabin pressure changed . . . all possibility was sucked into the vortex of this hunched and scowling apparition. The indifference bordering on naked hostility was palpable.

Bourdain goes on to describe with pained honesty, the extraordinary success of the Food Network after his departure:

[Food Network succeeded because it] was about likable personalities, nonthreatening images and making people feel better about themselves . . . This, I have come to understand, is the way of the world. To resist is to stand against the hurricane.

Bourdain is thought of as an artist— “the talent” as they say in show business—but he doesn’t get enough credit for being an extraordinary leader as well. The quality of his TV work owed a lot to his gift for what my chef-mentor used to call “the motivation-slash-manipulation” of people.

In a posthumous “Behind the Scenes” episode of No Reservations, his old crew describe, with great warmth and wistfulness, what an impossible boss he was—unconcerned with budgets, impatient, incredibly demanding, prickly about being “directed” in any way.

His management technique, copiously illustrated with “outtake” footage, was to expertly wield a kind of stage irascibility, an irascibility that was opaque enough to engender the nervousness and uncertainty that produces good work, but transparent enough that it could never be mistaken for cruelty.

In his last few years, Bourdain, who had long been interested in Gracie Brothers Jiu Jitsu and was separated from a woman who had become a full-time MMA fighter, renewed his interest in the discipline and devoted hours of his day to practicing. This regimen, which would have exhausted even a much younger man, coexisted with Bourdain’s hectic schedule, his hard drinking, pot-smoking and prodigious eating, his punishing travel itinerary. Because Bourdain came to fame and success late, it’s possible that he considered his years of struggle and obscurity to be a  kind of parenthesis to his real life, in the manner of Tennessee Williams, who took four years off his true age because that period where he worked in the shoe factory didn’t count.

kind of parenthesis to his real life, in the manner of Tennessee Williams, who took four years off his true age because that period where he worked in the shoe factory didn’t count.

The images from Bourdain’s final years show someone who has gone from being a handsome, well-fed middle-aged man to a strange, almost cadaverous figure whose face has lost its subcutaneous fat and whose appearance, like one of Giacometti’s attenuated, suffering creatures (R), seems to betray the evidence of a harrowing inner struggle. To view your body as an amusement park is a risky thing, especially if it is held in place by the carpet-bombed synapses of a former chef, former junkie and current alcoholic, of a lifelong New Yorker, of a constant world traveler.

Additionally, and perhaps not coincidentally, Bourdain took up with a much younger woman, a troubled Italian actress named Asia Argento. Bourdain loved tough women. Argento was pretty, she was covered in tattoos, she was an artist, a survivor, and best of all, she had serious underground cachet—she was the daughter of the grillo horror film director Dario Argento.

In the Rome episode of Parts Unknown (unavailable on most platforms for reasons that will become clear), you can see a stricken Bourdain falling in love with Argento as she whistles her approval at a boxing match by sticking her pinkies in the corners of her mouth, ragazzo-style, or twerks with a group of transvestite prostitutes they encounter in a seedy supermarket.

.jpg)

I interviewed Bourdain at the time his breakthrough book Kitchen Confidential: Adventures in the Culinary Underbelly came out in 2000. The interview, conducted by telephone, was a sidebar for my review of the book.

In the review, I had observed:

In the review, I had observed:

Written for the Gracious Living industry, most chefs’ books portray restaurants as clean, organized, sane places to work; the typical chef’s memoir, usually in the form of a preface to his cookbook, relates a few early food epiphanies followed by an account of a career with an unbroken upward trajectory.

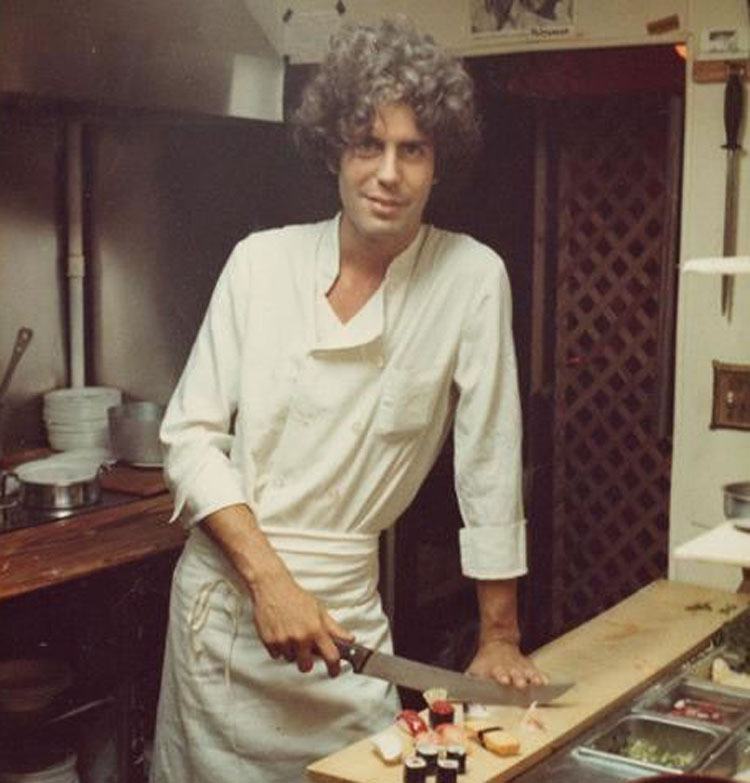

Bourdain’s book, which alternates memoir with accounts of typical, often disconcerting, kitchen practices and reportage about other chefs and other food cultures, portrays a career warped by arrogance, paranoia and constant drug use. A well-born misfit, he came up in the ’70s, a time of genuine anarchy in the restaurant business. Hunter S. Thompson was an early role model, and Bourdain recounts his own excesses with real Gonzo verve:

When the restaurant opened, we’d begin every shift with a solemn invocation of the first moments of Apocalypse Now, our favorite movie. Emulating the title sequence, we’d play the soundtrack album, choppers coming in low and fast, the whirr of the blades getting louder and more unearthly, and just before Jim Morrison kicked in with the first few words, “This is the end . . . my brand-new friend . . . the end,” we’d soak the entire range-top with brandy and ignite it, causing a huge, napalm-like fireball to rush up into the hoods . . . just like in the movie.

I have been hesitant to retrieve the recording of my interview with Anthony Bourdain for a number of reasons. My garage is a disaster area. It’s been difficult to locate a tape player—that’s how long ago it was. There’s the feeling of not wanting to hear the voice of someone recently dead. And, worst of all, I‘m embarrassed.

When my editor handed me a review copy of Kitchen Confidential with a “you’re gonna love this” twinkle in her eye, I was of course reluctant to read it and buried the book in an obscure corner of my apartment until the last minute. I read it at first with a dutiful sense of urgency which quickly became delighted absorption.

When I finished it, I was moved. I’d laughed a lot, I was impressed by the painful honesty and even more impressed by the effortless way Bourdain had mastered the difficulty about writing about food and restaurants in a fresh, energetic, and clear way. A restaurant is an institution where a thousand things go on at once and each individual thing has its individual thingness. Describing the whole picture with a combination of vividness and concision takes the skill of master caricaturist. As for the hazards of writing about food, Bourdain once put it in a characteristic way, using what was probably the first comparison that came to mind:

Trying to conjure a descriptive for salad must be like one’s tenth year writing ”Penthouse Letters”: the words ’crunch,’ ’zing,’ ‘tart,’ and ‘rich’ are as bad as ‘poon,’ ‘cooter,’ ‘cooz,’ and ‘snatch’ when scrolling across the brain in predictable, dreary procession.

I was blown away, but I was also—and here is where the cavalcade of embarrassment begins—I was jealous and a little angry. I, after all, spent my days in the same milieu as Bourdain, with a deep fryer to my left and a gas grill to my right, with a thick, greasy rubber mat beneath my feet and fissured ceiling tiles and fluorescent lights above my head. I worked with the same type of colorful sociopaths as Bourdain. As a matter of fact, I had just fired my sniffling, cocaine-dealing pantry cook for chronically oversleeping—and he had to be at work at 3 in the afternoon! Why, I wondered, had Bourdain, this Columbus of the near-at-hand, and not me written the book? Wasn’t I talented and perceptive as well?

When the time came for the phone interview, I had unconsciously resolved to make the interviewer’s cardinal mistake—a mistake that Bourdain, always an excellent listener even after he became world-famous, never made—I turned myself into the star of the conversation.

The phone call started off fine—Bourdain mentioned Orwell as an inspiration and insisted that he was nothing but a journeyman chef competently executing someone else’s menu. He singled out the then-new French Laundry Cookbook as “pure food porn,” which he explained (I had not heard the term before) was the “highest praise you could give.” He recounted with pride that he’d recruited a cook out of a Texas prison and said he planned to beat the odds and keep cooking, even into old age. Media-savvy already, he even gave me a great sendoff soundbite— “You never see young pigeons or old chefs.”

This was, of course, the perfect moment to wrap up the interview, which we both knew would end up as two-hundred-word sidebar in a third-tier independent newspaper. But I couldn’t stop talking. What did he think of (obscure French chef) or (English chef only known to insiders)?

At this point on the tape, you can hear a certain amount of background noise emerge on Bourdain’s end. He has moved, probably from the dining room of his restaurant in its between-service lull to what sounds like the kitchen. You can hear muffled shouts and what I imagine is the clang of aluminum sauté pans being slapped onto cast-iron burners, hot sheet pans sizzling into soapy water, the telegraphic click of a ticket machine.

And something changes in Bourdain’s voice. Though he’s far too polite to tell me to wrap this up because isn’t it clear to a fellow chef that it’s Saturday at 4 and obviously I have to get back to work, right now, a certain spring goes out of his voice and his sentences become more clipped. But I still can’t stop myself. What about (obscure British culinary writer)—wasn’t he in fact an inspiration for the book? And (forgotten underground writer), didn’t he influence Hunter Thompson, who in turn influenced Bourdain?

This goes on for quite a while.

Ten years after Kitchen Confidential was published, Bourdain wrote another book, Medium Raw, that reflected on the phenomenon of his breakthrough book, Kitchen Confidential, and his subsequent books and TV series. He changed first food writing and then food TV and then travel television in the transformational way Brando changed acting or Dylan changed popular music or Hemingway changed American fiction and journalism.

Kitchen Confidential’s impact was like The Wild One’s or The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test’s: it described a small subculture, but so vividly and so seductively that it managed to turn that subculture into a much larger phenomenon.

Kitchen Confidential was the work of a first-rate writer. Bourdain had solved the fundamental problem of any writer, the problem of voice. As Saul Bellow once wrote: “A writer should be able to express himself easily, naturally, copiously in a form that frees his mind, his energies. Why should he hobble himself with formalities? With a borrowed sensibility? With the desire to be ‘correct?'”

Bourdain’s voice owed a lot to Hunter Thompson; Bourdain learned from him how to deploy the high/low style: Thompson would go on for pages in lurid detail about his massive drug and alcohol intake and then he would sneak in a piece of sesquipedalia like “atavistic” (to describe his love of shotguns).

Bourdain also learned from Thompson an approach that favored the “back” rather than the “front.” Theodore White could vaporize about the brief majestic Camelot-like promise of the Kennedy administration, but in Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’ 72, Thompson wrote less about the candidates’ high-minded hopes for the Republic than about the poetry-writing egghead Eugene McCarthy standing outside a shoe factory at quitting time, his outstretched hand ignored by the working stiffs walking briskly to their vehicles, or Thompson nearly blowing up a campaign plane with his lit cigarette, or being privileged a long car ride with the tightly wound Nixon because the candidate wants to relax by talking about football.

The “front” is the officially approved version of the story. The “back” is the story behind the story—the “real” story.

But “front” and “back” also have another sense. In their book The Rebel Sell, Joseph Heath and Andrew Potter write of the distinction between front and back in restaurants and theaters:

The front is the place for customers, hosts, clients, service staff and members of the audience, while in the back we find kitchens, toilets, boiler rooms, dressing rooms and so on, Customers have access only to the front, while performers and waitstaff have access to both the front and the back.

The existence of the back implies a certain mystification, a place where there are secrets, props or activities that might undermine the ‘reality‘ of what is going on out front. Inevitably, the mere possibility that there might be a ‘back’ gives rise to a sense that the ‘front’ is manufactured and artificial, that the back is where the real or authentic is to be found.

The high/low style worked differently on the screen than it did in print. On the page, it was the profanity and demotic speech that shocked, but on television, when Bourdain spoke the words he had written for himself in his resonant and well-modulated actor’s baritone, it was the lapidary phrases and elevated speech that stuck out in a new and strange way.

Bourdain was a huge fan of The Simpsons and Letterman and little that he said was delivered without a raised eyebrow. Born in 1958, he had grown up, like the rest of his Boomer generation, watching a few too many episodes of The Waltons and Wild Kingdom, absorbing a few too many perorations, too many closing bits of orotund narrative delivered as the sun sets over Walton’s Mountain or on the African Savannah. This meant, to the delight of his audience, that he could never “do” the voiceover entirely straight.

Bourdain had something else that was rare on television and even rarer in a writer: charisma. He was both Cyrano and Christian—he had the carved, asymmetrical good looks of a veteran character actor and that actor’s mobile voice. He had a screen actor’s ability to broadcast small changes of emotion. From certain angles, Bourdain looked strikingly like Bogart—and, like Bogart, he could effortlessly become the conscience of the audience.

Bourdain’s epigrammatic, streetwise, and iconoclastic voice was likewise perfectly suited to social media, which distrusted the established and credentialed and elevated the marginal and self-promoting. Bourdain’s status as an outsider and a fuckup and his instinctive populism dovetailed with the natural anarchy of the digital universe. As he had found in his writing and on television, and as his enormous social media following attested, he continued to grow in fame and esteem because he had the knack for finding the right tone for the right medium at the right time:

Stuck in traffic in Bali. I think the EAT PRAY LOVE bus tour might have broken down.

Yeah yeah yeah, I know. I’m a crank. But the word ‘royals’ just…will never go down easy. Only person I ever felt comfortable referring to as ‘Prince’ came from Minneapolis.

When Harvey Weinstein was indicted for rape, Bourdain helpfully tweeted the weekly menu for the New York State Department of Corrections.

.jpg)

Beginning with the opening of the restaurant Chez Panisse in 1971, America had undergone a food revolution—although that food revolution was, at the time Kitchen Confidential was published, stuck with an antiquated mode of expression. At the time Bourdain appeared on the scene, most food writing and food television seemed cut off from the rest of the culture. Many food editors, food writers, and restaurant critics, like Maria Guarneschelli, Barbara Kafka, Gail Greene, and Mimi Sheraton, had been at their posts since the early Seventies. The reigning style was the “gourmet’’ style—at once arch and breezy, folksy, and Francophilic.

Beginning with the opening of the restaurant Chez Panisse in 1971, America had undergone a food revolution—although that food revolution was, at the time Kitchen Confidential was published, stuck with an antiquated mode of expression. At the time Bourdain appeared on the scene, most food writing and food television seemed cut off from the rest of the culture. Many food editors, food writers, and restaurant critics, like Maria Guarneschelli, Barbara Kafka, Gail Greene, and Mimi Sheraton, had been at their posts since the early Seventies. The reigning style was the “gourmet’’ style—at once arch and breezy, folksy, and Francophilic.

A critic might disparage the service at a restaurant by saying that the staff was “insufficiently acquainted with the pleasures of the table,” as a reviewer for Gourmet wrote in the early 90s. The best food writer of the time, Jeffrey Steingarten, was a Harvard-educated lawyer who researched and wrote his articles like legal briefs-his overriding message was that he knew more about his subject than you ever could.

If there was a pantheon of American food writers, it seemed to exist by default, because more robust talents had stayed away from the subject; the pantheon always managed to include the British transplant M.F.K. Fisher (above, R), who wrote in a twee, periphrastic style, closer to the 18th century than the 20th:

He may have heard that oysters or a glass of port work aphrodisiacal wonders, more on himself than on the Little Woman, or in an unusual attempt at subtlety augmented by something he vaguely remembers from an old movie he may provide a glass or two of champagne, but in general his gastronomical as well as alcoholic approach to the delights of love is an uncomplicated one which has almost nothing to do with the pleasurable preparation of his companion.

In food television, the standard was the long-running Great Chefs series, which stuck to an unvarying template: moldy Big Band music on the soundtrack, B-roll of whatever landmark denoted the city of choice (Golden Gate Bridge for San Francisco, Empire State Building for New York), a few shots of a well -appointed dining room with its chandeliers, crystal, and elaborately folded napkins, followed by a stand-and-stir segment in which a chef cooked and assembled one of his best- known dishes.

Bourdain instinctively understood that for a form of expression to be quintessentially American, it needed to have a reckoning with populism, with the way Americans actually spoke, consumed, and moved. This had also been true of Pauline Kael’s approach to criticism or Dylan’s to music or Bellow’s to the novel of ideas.

Sometimes this meant attacking a straw man—or attacking the establishment which had once—but no longer—represented mass taste. On his debut recording, Bob Dylan disparaged the songs nowadays that are being written uptown in Tin Pan Alley, but the truth was these songs had once been America’s music. Craig Claiborne had been the quintessential gourmet, but his typical reader wore a suit and tie not just at work but at home and at his church and listened to Andre Kostelanetz and read the Book of the Month.

Bourdain wrote for an American who barely existed in the pages of the food press: someone who was intelligent but who had demotic tastes, who was direct in her expressions, who probably had a few tattoos, listened to rock, hip-hop, and punk and who would get the chef’s frequent pop cultural references. This reader cared about where her food came from and who made it. Bourdain’s quarrel with the food media establishment was that they represented the vanishing breed of food writer and “gourmet,” who claims to love food yet secretly loathes the people who actually cook it.

Bourdain was not alone in challenging the food writing establishment. Ruth Reichl, an “old hippie” as she called herself, became editor of Gourmet in 1999. As restaurant critic for the New York Times, she had made her mark with a famous review that broke down the traditional barrier between “front” and “back”: she wrote a review of Le Cirque, at the time the society table in New York, which was actually two reviews: one of her experience when she wasn’t recognized as a Times reviewer and one when she was.

In L.A., Jonathan Gold, a gentle, brilliant, deeply introverted writer who, like Bourdain, came out of a milieu of punk and avant garde music, wrote about the city as what David Rieff called it—the Capital of the Third World. Gold was as likely to review a Fukenese restaurant in an Orange County strip mall as he was Wolfgang Puck’s latest venture. He put food trucks on the map, and once described being transfixed by a spit of pork on a taco truck as if he were watching the last few minutes of the World Cup.

Bourdain also benefited from another shift in society from the “front” to the “back”: the craze for what came to be called Misery Lit or autopathography.

Where memoirs had once been the domain of the ancient and distinguished, now they accommodated stories of teenage self-harm (Marissa Hornbacher’s anorexia/bulimia memoir Wasted), bipolar illness (Prozac Nation), and incest (The Kiss). Though where Kitchen Confidential differed from every other Misery-Lit chronicle was in Bourdain’s defiant refusal of self-pity.

Reality TV, with its emphasis on “keeping it real” —which meant revealing painful personal secrets to the world and constantly stoking any potential source of conflict—began to take over television with the debut of The Real World in 1992. Although it had its roots in political engaged, spontaneous cinema verité, reality TV soon began to seem as spontaneous as a Busby Berkeley musical.

The combustible assumption that coursed through all of these new energies was that where we are at our lowest is truest to our nature.

Bourdain, for example, always insisted that, despite all his success, he was an ex-junkie at heart. He believed that this gave him a superpower that was indispensable in the counterfeit world of show biz:

Well, particularly in the world of television, but it’s also true I think in any media: there are a lot of people out there who are full of shit . . . There are the type of people who say they’re going to do something tomorrow and they actually do it, and then there’s everybody else. And having been a heroin addict you too develop some skills as far as judging which type of person that it might be you’re dealing with, or you end up dead.

In the first few episodes of A Cooks Tour, Bourdain looks like someone who has escaped from late-night public access TV, and the show’s production values are somewhere between an ad for a local furniture warehouse and a DIY New Wave video. In an oral history published in GQ after Bourdain died, Lydia Tenaglia, who ran Bourdain’s production company and oversaw all of his TV shows, remembers how, after a shaky beginning, his style began to emerge:

Part of us thought that he may never come back. (He did.) Then we flew to Vietnam. Suddenly he looked around and he had this instant cultural touchstone. His idea of Vietnam, Japan, and Hong Kong all emanated out of literary and film references. And of course he was a voracious reader, one of those just preternaturally gifted people that could absorb what he had read and retain it. He wanted to connect what he had read with actual experience of that in a very romantic way . . .

He came alive, because those frames of reference were starting to pop. His sudden inclination was to turn and share that with us. You could sense this excitement, like, “Holy crap, I’m actually on the ground in a location that I have studied, that I know, that I have references to.” You know, Apocalypse Now, Heart of Darkness, Graham Greene, the Vietnam War. He was percolating with an excitement that was very genuine.

Bourdain was also a true cineaste and had grown up during what could be called (to borrow a phrase of Philip Lopate’s) “The Heroic Age of Moviegoing.” As he became more confident, and more established, and seemingly a little bored with the limits of describing and filming food and restaurants, these things receded and the movies, books and music he loved became even more prominent.

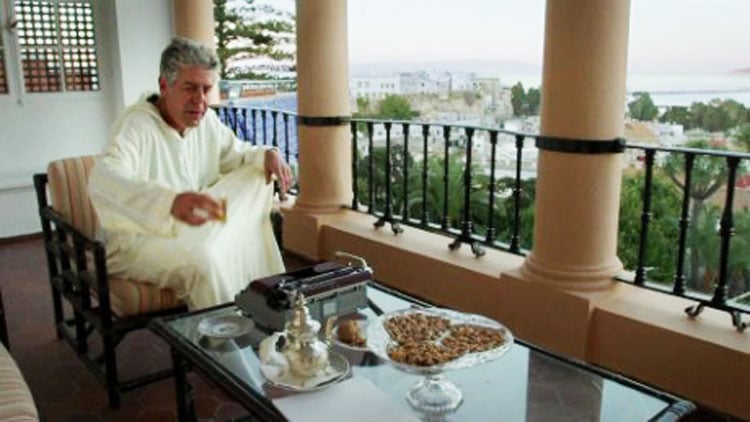

Of all the precredit sequences on No Reservations or Parts Unknown, the best is the one that opens the Tangiers episode of No Reservations.

It begins with an out-of-focus shot of a figure in white. Synthesized rumblings of indigenous music on the soundtrack. A glass of mint tea being poured in slow motion so its texture resembles boiling oil. The tea dissolving into a flock of gulls, so the gulls seem to be emerging from the tea. The white-clad figure comes into focus: Bourdain, wearing the native dress, a collection of local snacks before him on a veranda, an unmistakable smirk on his face, a smirk edging upwards into a sneer. The birds head towards sea, flying over a collection of minarets. The sun sets. The cry of the muezzin is heard. Bourdain in voice over: “I’ve always wanted to get as far away as possible from the place I was born. Far both geographically and spiritually. To leave it behind.”

The screen turns to black, with a doorway-sized space cut into it, showing Bourdain’s ungainly figure ambling down a cobblestone alleyway, lit by that unmistakable yellow-green light of the Mediterranean nighttime street. The screen goes completely black, superimposed with Paul Bowles’s birth and death dates.

The Tangiers sequence is essential Bourdain: sensual, exotic, cinematic, musical, wistful, literary, autobiographical and ironic (that smirk, probably impatiently directed towards his crew who have asked for yet another take). Retrospectively, the choice of the Bowles quote seems especially resonant, and the self-hatred at its core unavoidable.

Bowles, an American who expatriated himself to Morocco, understood as well as anyone that travel could be an intoxicating escape but also a pathway to the scariest and most disorienting truths about oneself and the world. In the Tangier episode, Bourdain mentions Bowles’s greatest work, The Sheltering Sky.

In that novel, the main characters, Kit and Port Moresby, travel to Morocco to rekindle their failing marriage. They make love, ecstatically, on a promontory overlooking the desert. Things seem better. But then, in a devastating postscript to the scene, Port borrows a bicycle at night and returns to the promontory by himself. The unmistakable implication of this little gesture is that he discovers that he is so alienated that he can only truly enjoy experiences in solitude.

The revelation of his own internal hollowness is too much. Shortly afterwards, as they journey into the interior, Port allows his passport to be stolen and lets himself contract a fatal dose of TB. His wife is then kidnapped by Bedouins, repeatedly raped, and driven mad.

In the underrated Bertolucci film of the novel, the theme of the disorienting effects of travel is beautifully suggested by the opening sequence, an extreme closeup of humanoid features, a shot which slowly pivots 180 degrees to reveal the right-side up face of a perfectly cast John Malkovich.

In the underrated Bertolucci film of the novel, the theme of the disorienting effects of travel is beautifully suggested by the opening sequence, an extreme closeup of humanoid features, a shot which slowly pivots 180 degrees to reveal the right-side up face of a perfectly cast John Malkovich.

Bowles was the coldest and most pitiless of writers, and his characters, with their sentimental ideas about exotic cultures and their dreams of unlimited freedom and bottomless pleasure, generally do not end up well.

Starting with the Tangiers episode, an increasingly despairing, disoriented and world-weary note begins to predominate in Bourdain’s work.

And a preoccupation with death: the death of civilizations, planetary death, ceremonial death.

Writing about food and drink means entering into a negotiation with pleasure. Without something transcendent underlying it, the act of expression becomes nothing but a testimony to animal satiation, to gluttony and drunkenness.

There is something a little off about people who dedicate their lives to pleasure. The Greeks, after all, created satyrs, those ambassadors of pleasure, as half-human, half-horse.

In old-school culinary writing, eating and drinking too much are merely venial sins—the payoff is connoisseurship, the pursuit of an occult knowledge that opens onto truths that are wider and deeper than food.

In a famous passage in Brideshead Revisited, Charles Ryder takes the parvenu Rex Mottram to a great Parisian restaurant. Because they are on Rex’s dime, Charles orders the best and most expensive bottles—a Montrachet and a Clos- de- Beze. Rex is unimpressed by the wine and chatters on as Charles is overwhelmed by the red, which “seemed a reminder that the world was an older and better place than Rex knew, that mankind in its long passion had learned another wisdom than his.”

This is, depending on your perspective, either a stirring defense of Western Civilization or insufferable snobbery.

Bourdain, in his food writing and television, appeared to be animated by two impulses that seemed to justify his pursuit of pleasure: the first was an instinctive populism, a fellow-feeling that at first glance appeared to have originated in his professional contact with the poor and mobile of Mexico, El Salvador, Ecuador, and China.

This populism led him to champion, sometimes truculently, street food sellers, line cooks, and dishwashers. On his TV shows, Bourdain would share food with the people who could be regarded as his historical antagonists: with Muslims, with Vietnamese, with black folk in the inner city and the Deep South. He would break bread, in the most profound sense of the term, to share and acknowledge a common humanity.

These scenes coexist on his shows with bacchanalia of food, drink, porn, weed and hash, almost as if they are a kind of penance for his excess.

There are books, articles, and shows about street food, bbq cooks, wok slingers everywhere now. But before Bourdain did a segment of A Cook’s Tour on the small town where his Mexican sous chef came from, it’s safe to say that not only had no one ever done anything like that—it’s quite possible that no one in the food media (with the possible exception of Jonathan Gold) had ever even thought of it.

Bourdain’s second impulse was a transgressive hedonism. Defying traditional beliefs about the pursuit of pleasure, which hold that that the search for constant sensory gratification leads to dissipation and ruin, he saw it as a pathway to authenticity and liberation.

A true product of the counterculture, Bourdain believed, in the William Blake by-way-of Jim Morrison tenet that “the road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom.”

In the opening paragraph of “Don’t Eat Out Before Reading This,” the New Yorker article that brought him instant notoriety, Bourdain expressed a transgressive impulse that his literary hero William Burroughs would have instantly recognized:

Good food, good eating, is all about blood and organs, cruelty and decay. It’s about sodium-loaded pork fat, stinky triple-cream cheeses, the tender thymus glands and distended livers of young animals. It’s about danger—risking the dark, bacterial forces of beef, chicken, cheese, and shellfish. Your first two hundred and seven Wellfleet oysters may transport you to a state of rapture, but your two hundred and eighth may send you to bed with the sweats, chills, and vomits.

And of course, bad mussels would leave him—in a phrase he liked so much that he reused it many times— “shitting like a mink.” The perils of digestion, which hitherto had been taboo in food writing, were a constant. “The inside of my head feels like Andrew Zimmern’s toilet,” he wrote after a rough night in Nicaragua.

Embracing the transgressive meant, like many other globe-trotting food celebrities (Andrew Zimmern above all), eating disgusting food—warthog anus, fermented shark fin, Hundred-Year-Old egg—and describing the consequences. But this was the least distinctive part of Bourdain’s project.

There was the constant use of porn as a, well, a touchstone. When E.M. Forster wanted to illustrate differences in national character, he described the very apposite reactions of Spaniards and English to a near-fatal carriage accident. For Bourdain, nothing illuminated a country’s temperament better than the porn he could command in hotel rooms around the world:

Japanese porn is ugly, violent and disturbing. German porn is ugly, fetishistic, and disturbing. American porn is stupid, slick and produced in multiple versions (how explicit depends on what major hotel chain you’re staying at). Brit porn, however, is the absolute bottom of the barrel.

One of the most notorious episodes of No Reservations was the “Food Porn” segment, painstakingly made to look like VCR-era smut and emceed by 80s porn superstar Ron Jeremy, wearing what looks like a prom tux and, bizarrely, playing a harmonica.

The transgressive was a constant in Bourdain’s search for a rule-free utopia, a place with “a high tolerance for bad behavior,” the phrase he used to describe the postwar Tangiers immortalized by Burroughs as the Interzone. He sought this utopia again and again, in Provincetown, San Francisco, South Beach, Key West, Vegas, Berlin.

There are good arguments to be made against creating the kind of society with no rules that Bourdain was always seeking; one is that such a society, no matter how well-intentioned and utopian it is meant to be, will be helpless against the sociopaths that are inevitably drawn to it.

This argument is also true of art: a culture that is not accountable to taboo or censorship will as a matter of course attract the genuinely subversive. Though the word “subversive” is nowadays used almost exclusively as a term of praise, to designate art that rightfully attacks the bourgeois or the conventional or the canon or whiteness it still retains vestigial pejorative sense. There are things that most of us can all agree are worth not subverting.

In the Tangiers episode of Parts Unknown, there is a portentous reenactment of Williams S Burroughs pounding out Naked Lunch on an old Underwood, as if we were watching Goethe in Weimar or Joyce in Trieste. Burroughs, Bourdain tells us, was “one of my heroes” and by far the greatest of the Beats. Naked Lunch is “a non-linear, dry- humored, searingly critical, profane masterpiece.”

In Naked Lunch, as in all Burroughs’s work, there is the overpowering presence of a hypnotic, levelling, deeply anti-humanist vision. His work is, like de Sade’s, an extreme manifestation of the nihilism and amorality inherent in the pursuit of pleasure. As a sensual experience, a cigarette has no more or less importance than a decapitation. You always encounter certain tropes: heroin, the deformed and the freakish, vast government/corporate conspiracies and concomitant paranoia, ephebophilia, and above all, the unsavory combination of hanging and sexual release:

My body was raw, twitching, tumescent, the junk-frozen flesh in agonizing thaw . . . I pitched forward and the rounded edge of the bench, polished smooth by the friction of cloth, slide along my crotch. Sparks exploded behind my eyes; my legs twitched—the orgasm of a hanged man when the neck snaps.

The best arguments against the pursuit of pleasure are to be found in the works of the most hedonistic writers. In the works of the Marquis de Sade (Burroughs was his true heir), pleasure is literally exhausting: the sexual experimentation always increases in elaborateness and perversity to the point where it destroys the body.

There is sensual despair caused by deprivation and there is sensual despair caused by excess. Burrough’s work is the soundtrack for the second of these—for a life characterized by non-stop transgression.

Burrough’s rallying cry, “In the US you have to be a deviant or die of boredom,” gives legitimacy to not just adolescent pursuit of pleasure but to adolescent self-destruction. It gives an energy and rebellious authority to your darkest and most self-destructive passing thoughts. Sometimes this comes out in Bourdain’s writing in the form of sick humor. He wrote, in 2006, about life on the road:

It doesn’t take a lot for us to laugh, not after we’ve been softened up by countless “hang-yourself-in-the shower-stall” hotel rooms.

Two weeks before his death, he wrote in reply to a Twitter troll:

Laughing about your demise by auto-erotic asphyxia in a public lavatory?

Let’s say that after each death, that particular life begins to shape itself into something like a coherent narrative. If that death is a suicide, the life transforms itself into a tragedy, with every incident appearing to lead inevitably to the act of self-murder. This may seem tendentious, but there is a lot of truth to it, especially in the case of the suicide of older people. Though suicide can be an impulsive act, particularly among teenagers and young adults; for older people, it is most often an act carried out only after long inner struggle and deliberation—the impulse towards self-preservation and away from irreversible self-harm is an enormously strong human instinct. Psychologists say that a suicide is overdetermined; in other words, that you need an overabundance of reasons to kill yourself.

One of the many things that made Bourdain’s death tragic was that he was so keenly aware of what was at stake in his own life.

In 2010, he wrote in “I’m Dancing” an essay about the uncool pleasures of being a father:

Norman Mailer described the desire to be cool as a “decision to encourage the psychopath in oneself . . . “

I encouraged the psychopath in myself for most of my life. In fact, that’s a rather elegant description of whatever it was I was doing. But I figure I put in my time.

The essence of cool, after all, is not giving a fuck.

And let’s face it: I most definitely give a fuck . . . There will be no more Dead Boys T-shirts. Whom would I be kidding? Their charmingly nihilistic worldview in no way mirrors my own.

Two years before his death, Bourdain wrote, in the introduction to his cookbook Appetites:

Tolstoy clearly never spent any time with my happy family.

My eight-year-old daughter does a terrific imitation of my wife threatening to choke a taxi driver. It’s something she’s seen enough to get dead right—my wife’s Italian accent, her anger, her exasperation as the driver takes yet another wrong turn on his way to my daughter’s school, and finally the kicker: “I’m going to keel you with my bare-a hands.”

Bourdain added:

From the second I saw my daughter’s head corkscrewing out of the womb, I began to make some major changes in my life. I was no longer the star of my own movie- or any movie. From that point on I, it was all about the girl. Like, most people who write books or appear on television, who think anyone would or should care about their story, I am a monster of self-regard. Fatherhood has been an enormous relief, as I am now genetically, instinctually compelled to care more about someone other than myself. I like being a father. No, I love being a father. Everything about it.

Sometimes a writer will write something because he believes it to be true. But sometimes a writer will write something—and more importantly, publish it—as a kind of promissory note to himself, in the hope that putting it out there will leave him no choice but to make it come true.

In the footage shot in 2001 for a documentary on Bourdain’s life, there is one incongruous figure: Bourdain’s mother (R). Sturdy where Bourdain was bone-thin, sporting penciled eyebrows and an elaborately folded scarf, using language to say exactly what she means rather than to charm and seduce, deeply skeptical of her son’s newfound success, Gladys Bourdain radiates old-fashioned propriety. She remembers what her son was like as a teenager using the phrase thought or uttered by so many long-suffering Depression-born parents about so many recalcitrant Boomer children: that she loved him but didn’t like him very much.

In the footage shot in 2001 for a documentary on Bourdain’s life, there is one incongruous figure: Bourdain’s mother (R). Sturdy where Bourdain was bone-thin, sporting penciled eyebrows and an elaborately folded scarf, using language to say exactly what she means rather than to charm and seduce, deeply skeptical of her son’s newfound success, Gladys Bourdain radiates old-fashioned propriety. She remembers what her son was like as a teenager using the phrase thought or uttered by so many long-suffering Depression-born parents about so many recalcitrant Boomer children: that she loved him but didn’t like him very much.

Bourdain revealed many embarrassing details about his life, but one he didn’t choose to share was that it had been his mother who was responsible for his big break: a copy editor at the New York Times, she had used her industry contacts to get the manuscript of “Don’t Eat Out Before Reading This” to New Yorker editor David Remnick.

You might be inclined to think that Bourdain was in permanent rebellion against his mother, but you’d be only half-right. Bourdain had his mother’s excellent manners and strong sense of propriety. To watch the many scenes on his various shows where he dines at someone’s home is to understand this and to appreciate that Bourdain was always more than a talented loudmouth, that he had so many noble and generous qualities.

He never makes himself too much at home. He chews with his mouth closed and knows how to use a knife and fork.

He asks question about and lavishly praises the food. He eats seconds and thirds. He draws people out. Though the focus is naturally on him, he doesn’t talk too much about himself. He’s grateful to be there.

And people respond—even in places where suspicion and animosity are still bone-deep, you see facial muscles relax and smiles spread as they lose their self-consciousness.

In 2001, while he was still a working chef, Bourdain published a brief biography of Mary Mallon (R). Typhoid Mary: An Urban Historical is a very weird book. It is a celebration of the cook who, through a combination of ignorance, doggedness and deviousness, managed to infect scores of people with typhus and kill at least three. Bourdain’s take on Mary is “the story of a proud cook—a reasonably capable one by all accounts, who at the outset, at least, found herself utterly screwed by forces she neither understood nor had the ability to control.” She adheres to the code of the proud cook, which is that “No one calls in sick.” Mary is demonized because she works in a despised profession, because she is a woman and an immigrant.

In 2001, while he was still a working chef, Bourdain published a brief biography of Mary Mallon (R). Typhoid Mary: An Urban Historical is a very weird book. It is a celebration of the cook who, through a combination of ignorance, doggedness and deviousness, managed to infect scores of people with typhus and kill at least three. Bourdain’s take on Mary is “the story of a proud cook—a reasonably capable one by all accounts, who at the outset, at least, found herself utterly screwed by forces she neither understood nor had the ability to control.” She adheres to the code of the proud cook, which is that “No one calls in sick.” Mary is demonized because she works in a despised profession, because she is a woman and an immigrant.

It’s hard to tell where Bourdain’s rage at Mary’s treatment ends and his own rage begins, the rage of a downwardly mobile middle-aged man who as a young man fell into cooking as a lark and for whom that lark has now turned into a life sentence:

Like Mary, I’ve worked for private clients. Briefly. Had I stayed on, had my boss asked me one more time for ‘an egg-white omelette—and no butter or oil in the pan,’ I would surely have grabbed hold of his skull, squeezed until his eyeballs popped out of his head like pachinko balls. Had I worked in the homes of the rich and silly circa 1906? I would have murdered them in their beds with the nearest available blunt object.

At the end of the book, Bourdain makes a pilgrimage to Mary’s grave in the Bronx and buries his prized carbon-steel knife in the earth beneath her headstone.

It’s as if a fellow doctor had written a monograph praising Dr. Crippen or Conrad Murray. Typhoid Mary is the ultimate celebration of the cadre over the civilians it purports to serve, like that famous bit from Full Metal Jacket in which the drill sergeant praises the achievements of Charles Whitman and Lee Harvey Oswald as “an example of what one Marine with a rifle can do!”

The book is also, in its populism and its spite and sick humor, a very Punk gesture, and a clue to Bourdain’s deepest impulses and most cherished values.

A few contradictory statements about Punk, all of them true:

It’s quintessentially English. It’s American in origin.

It’s primitive in both execution and expressive content. It’s the highly self-conscious, sophisticated product of art school graduates.

It’s inconceivable apart from drugs, especially heroin and glue. It’s about the straight-edge life-living an authentic existence without drugs.

It’s apolitical. It’s nothing but political.

Punk is about nothing but fashion. Punk is anti-fashion.

It’s Year Zero art. It’s the latest flowering of a topos you can trace back to Paris in the 1850s.

It is about the gesture of solitary defiance and spite and self-degradation—the term ‘Punk’ comes from prison slang: a punk is a hapless sexual plaything passed around to other inmates. No, the point of the term ‘Punk’ is not that you are degraded but that you are no better than anyone else—it’s about the gesture of solidarity.

The Symbolist poets would have saluted the Punks as kindred spirits. Nerval, who walked a pet lobster around Paris, would have understood their outrageous personal conduct; Lautreamont, whose hero, Maldoror, fornicates with a shark, would have enjoyed the sexually extreme band The Leather Nun; Rimbaud, who wrote a “Sonnet to an Asshole” and spoke of the “systematic derangement of the senses” would have appreciated their transgressive spirit. And Baudelaire would have fit right in; Baudelaire, who rhapsodized about the liberating power of opium in Les Nouriturres Terrestres, celebrated the beauty of decay in his famous paean to a rotting female corpse, and gave the nineteenth century its most powerful expression of nostalgie de boue in Les Fleurs du Mal.

Indeed, the Punks were huge fans of the Symbolists and saw them as spiritual ancestors.

Ronald Sukenick’s Down and In (1987) is at once a memoir and a history of what has been variously called Bohemia or the Underground or the Counterculture.

Sukenick was like Bourdain, a nice Jewish boy from the tri-state area drawn to the hipper parts of downtown Manhattan. What makes Down and In valuable is that, like an issue of New Masses from 1937, it gives as pure a statement as you are likely to find of its ideology’s core principles. Sukenick traces these principles to mid-19th century Paris, where they were incubated and exported more or less intact into mid-century Manhattan:

Much of the attraction of the underground derives from the circumstance that it pursues the tiger of pleasure instead of yoking itself to the oxen of duty.

Bohemians do what they feel like. Desire becomes a positive force rather than one to struggle with.

Ultimately a democracy can be based only on people doing what they want to do. That is a fact that lawyers may not like but artists can understand.

Subterraneans . . . are among other things researchers in the risky discipline of living in contact with the deepest impulses.

A shmuck [here you could substitute less pungent words like square, straight or suit] is somebody with a certain way of thinking, a combination of caution, conformity and mercenary values.

I would come to understand the flagrant self-destructiveness of the underground of Bleecker Street is an expression of its total contempt for the cautious pragmatism of the middle class.

And finally, there’s this, borrowed from the critic Anatole Broyard, a description of the habitues of the Remo bar, a phrase that, if you dusted off its midcentury Freudianism, could serve as an epitaph for Bourdain:

Hovering halfway between the pleasure principle and the death instinct.

The values of Bohemia—failure as success, self-destructiveness as self-discovery, contempt for the squares, and a commitment to the search for what one of Baudelaire’s first champions called “a new frisson” —were those of Punk as well. Punk added a soundtrack inspired by the crudest and most energetic expressions of rock and roll. It also repainted the bohemian template with its own lurid color scheme, a palette that was inseparable from Punk’s base inspirations: rockabilly pink, Stormtrooper black, nuclear waste green, pus yellow, straightjacket white, heroin red.

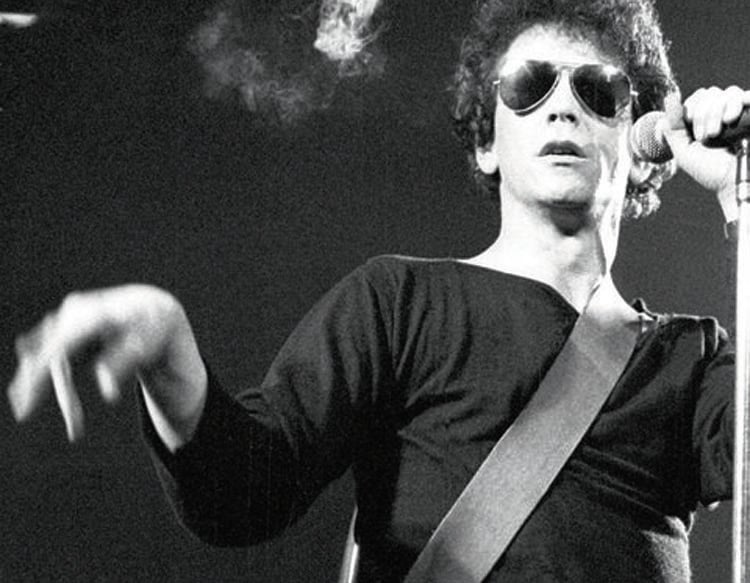

Heroin was indispensable to the Punk cultural apparatus. Lou Reed sang about it in his most famous song (“It’s my wife and it’s my life”) and mimed shooting up onstage; Sid Vicious died from a self-administered overdose of it while awaiting trial for murdering his girlfriend; Dee Dee Ramone hustled for his habit and wrote a famous song about hustling (“53rd & 3rd”); Jim Carroll sold his body for his own habit and wrote a famous song about the grisly deaths of his friends, including from heroin use (“People Who Died”); Johnny Thunders was such a notoriously self-destructive heroin addict that the Replacements wrote a song about him (“Johnny’s Gonna Die”). Johnny hung on for a while, but he did die.

Heroin was dangerous, it was transgressive, and it put its users in a milieu where they had no choice but to indulge their own nostalgie de boue. The sleazier and more degrading the better. Luc Sante, who was an addict in New York at the same time as Bourdain, described the dirty glamor of the Walk on the Wild Side:

But lately you have surprised yourself outside a slot in a door in some ruin a couple of blocks over in the empty quarter and handing over cash in exchange for bags. You tell yourself you will never be one of those people who stand for hours in the rain being toyed with by the lookouts, shuffled from one side of the street to the other, made to show track marks at the base of the steps, suffered having the slot slap shut definitively, just as you are finally stepping up to it.

Punk was a combination of the same impulses that fueled Bourdain’s approach to pleasure: transgression and populism.

Here, from a 1978 article by Peter Silverton, is a vivid account of a kid who has wandered onstage during a Clash show, one which gives an understated description of punk’s democratic ethos:

Benignly ignored by band, stage crew, and security alike, he wanders around the stage a little drunkenly, uncertain quite what to do now that he’s made it up onto the hallow, sacrosanct boards and is not making quite the impression he thought. Decision flickers across his face, lit by the giant spots, and he grabs hold of the singer’s mike and prepares to join in on the harmonies.

When the singer wants his mike back, the kid’s frozen to the stand in fear-drenched exhilaration so the singer has to shout his lines over the kid’s shoulder while the kid pumps in the response lines on perfect cue.

Punk was also the product of a city and era synonymous with decay, sleaze and anarchy: New York in the 70s.

The “Lower East Side” (LES) episode of Parts Unknown, filmed two months before Bourdain’s death and completed after it, is not easy to watch. The subject matter is dark and depressing. The New York portrayed is a battered Troy of the mind, haunted by its vanished multiple pasts.

Bourdain looks, well, like a ravaged old man who is returning to the scene of his youthful ruin, animated by an eerie and unmistakable nostalgia. In his poem on A.E. Houseman, Auden uses the striking phrase “the money of his feelings” to describe Houseman’s bruised retreat into the safe world of antiquity. After his death, it’s hard not to think that the core of Bourdain’s emotional investment—the money of his feelings—had always been here, in the unbearable excitement and the unbearable trauma of his youth—in this sensorium of killer music, extreme behavior, bombed-out buildings, and industrial-strength drugs.

New York in the 70s was dangerous, anarchic, and thrilling. For the very last time, the city became what it has always promised to be for young artistic types: not just an affordable milieu in which to practice their art, but a place where you could be guaranteed a privileged view of the new modes of human expression that would one day take over the world. As the LES episode shows, New York in the 70s birthed not just punk but hip-hop, graffiti art and break dancing. New York’s mix of punk, heroin, and graffiti art also nurtured the last great painter the city has produced—Jean-Michel Basquiat.

The LES episode, the final Parts Unknown ever completed, is a loving tribute to Bourdain from the people he left behind. It is assembled into a kind of overcrowded frenzy, like a spontaneous memorial wall—the film distressed to resemble an old VCR tape, with little sequences repeated in a rhythmic staccato way as if the editing apparatus were attached to a hip hop turntable. The screen is painted over like an action painting. Image and music do furious battle. The opening voice over, written by Bourdain, could be taken from Baudelaire:

New York City during the 1970s was a beautiful, ravaged slag. Impoverished and neglected after suffering from decades of abuse and battering, she stunk of sewage, sex, rotting fish and day-old diapers . . . she leaked from every pore.

Bourdain interviews Blondie’s Debbie Harry and Chris Stein, hip-hop pioneer Fab Five Freddy and Richard Meyers, better known as Richard Hell (the “Hell” is a nod to the Rimbaud prose poem). Here is Richard Hell, funny and low-key, still living on the LES after all these years, a Slave of New York chained to his rent-controlled apartment. Bourdain credits Hell with originating the world-famous punk look of spiked hair, safety pin and ripped t-shirt. The look was immediately appropriated, according to Bourdain, by Malcolm McLaren, manager of the British Punk band The Sex Pistols (“they were like a boy band—he told them where to go and what to wear.”)

Some of the old footage is hilarious. Here is James White and the Blacks (“Bands are forming of people who have never picked up a musical instrument and aren’t sure what end to put in their mouth” —Luc Sante): A mercifully brief clip of the band curb-stomping James Brown’s funk classic “I Can’t Stand Myself” with the musicians playing whatever the opposite of a groove is.

“If Stiv Bators were still alive and put his filthy hands anywhere near my baby, I’d snap his neck—then thoroughly cleanse the area with baby wipes,” Bourdain had written. But here are the Dead Boys, led by the snot-nosed Stiv Bators in all his septic glory.

Bourdain recalls the bombed-out squats where he used to score. He’s always been, it seems, a true Romantic, a lover of ruin and decay. (In the Detroit episode of No Reservations, he wanders through a block-long former Pontiac factory, now open to the elements, with its windows bashed out, overgrown with weeds and graffiti. He makes a dutiful comment to his guide about what a loss of livelihood this represents, but he can’t contain himself: it’s just so beautiful.)

He visits a character who collects old dope bags, those little see-through plastic envelopes used to sell heroin. Dope has always had a brand name—this is a running joke on The Wire, where the moniker— “Pandemic” or “WMD” —is something that might attract addicts but would make the rest of humanity steer clear.

For Bourdain, the dope bag museum is a trip down Memory Lane. Here are “DOA” and “Poison.” Here is “Toilet,” with a cartoon of a toilet on it. Bourdain says, with an unmistakable note of wistfulness in his voice, “You knew you were doing something bad when you bought a product called ‘Toilet,’ and, you know, shot it in your arm. Oh man, memories.”

“Lower East Side” closes with a montage of the episode’s images, with a soundtrack of what sounds like a ringer doing a credible imitation of Johnny Thunders’ curdled baritone on “You Can’t Put Your Arms Around a Memory.” The song, like Lou Reed’s “Coney Island Baby,” bares the soft doo-wop heart of Punk.

The backing vocals are sung by Bourdain’s 12-year-old daughter.

In Medium Raw, Bourdain wrote, in an essay about Food Network:

But my low opinion of the Food Network actually went back a little further in time. Back to when they were a relatively tiny, sad-sack startup . . . You know the stuff: happy ’customers’ awkwardly chawing on surf and turf, followed by’ Chef Lou’s cheesecake . . . with a flavor that says’ Ooh la-la!…

I was invited to cook salmon . . . I arrived to find a large and utterly septic/kitchen prep area, its sinks heaped with dirty pots and pans, refrigerators jammed with plastic-wrapped mystery packages that no one would ever open. Every surface was covered with neglected food from on-camera demonstrations from who knows how long ago, a panorama of graying, oxidizing, and actively decaying food beset with fruit flies . . . Once in the studio, cooking on camera was invariably over a single electric burner, which stank of the encrusted spills left by previous victims.

Something has nagged at me for years about this passage. And then it occurred to me—that scene in The Catcher in The Rye in which Holden watches the budding date rapist Stradlater shave:

Stradlater was more of a secret slob. He always looked all right, Stradlater, but, for instance, you should’ve seen the razor he shaved himself with. It was always rusty as hell and full of lather and hairs and crap. He never cleaned it or anything. He always looked good when he was finished fixing himself up, but he was a secret slob anyway, if you knew him like I did.

Bourdain’s fastidiousness, like Holden’s, had always been one the few qualities he could hold on to keep from completely falling apart, and in the Food Network kitchen, the combination of the trite and insincere onscreen content (Chef Lou’s cheesecake…with a flavor that says’ Ooh la-la!”) with the filth behind the scenes amounts to a moral betrayal— failure of authenticity.

Bourdain, like Holden, was hypersensitive to the counterfeit: he hated anything that was “staged” for the camera; in the Sicily episode of Parts Unknown, his local fixer arranges a scuba diving episode and throws obviously dead calamari in the water for Bourdain to “catch.” Bourdain responds by becoming apoplectically furious (This is Sicily-what did he expect!) and pounding a dozen Negronis on camera.

The Catcher in the Rye, even more than On The Road or Growing Up Absurd or Bringing It All Back Home, launched countless American authenticity projects, probably including Bourdain’s. It’s even clearer after his death that Bourdain’s virtues, like Holden’s, were adolescent virtues: the relentless honesty, the charming combination of egalitarianism and snobbery, the need for constant stimulation, the endless energy, the desire to shock and the love for the transgressive, the mortar of cynicism holding up the lofty romanticism, to use Boris Johnson’s phrase.

All of this would have been survivable, but Bourdain was also the worst kind of fanboy. The best interpretation of this would be to say that he was as loyal to the enthusiasms of his youth as he was to his old friends.

When he called William S. Burroughs, or Iggy Pop or Hunter S. Thompson or Keith Richards his heroes, he meant just that—the role model, the idol whose life is the exemplum. You could, after all, enjoy the art, marvel at the charisma but deplore the conduct and the beliefs that underwrote the conduct. Or you could be indifferent to the art and celebrate the conduct. But Bourdain went all in.

The connection between Bourdain’s relationship with Asia Argento and his eventual suicide would remain a matter of idle conjecture and intramural gossip if it weren’t for a couple of media postings.

In June 2018, a few days before Bourdain’s suicide, TMZ posted a few photographs taken by a paparazzo showing Asia Argento embracing and holding hands with a handsome man closer to own age.

Bourdain had met Argento in 2016. She had revealed to him that she had been raped by Harvey Weinstein and he encouraged her to come forward with the story. She had been one of the first prominent actresses to allow her name to be used in the Weinstein investigation. She had spoken to journalist Ronan Farrow and he had used her story in a massive article on Weinstein the New Yorker published in November 2017.

She had said Weinstein had raped her in 1999, while he was producing a movie she was starring in. She added that, after the rape, they continued to have a sexual relationship for five years, this time consensual. He had even introduced her to his mother. She had said that she was afraid he would ruin her career if she stopped sleeping with him.

It was hard to know what to make of this story. The media in America were initially sympathetic towards Argento. But the Italian tabloid press reacted with gleeful, braying skepticism and painted her as a slatternly opportunist. She found the treatment hostile and threatening and said that it forced to her leave the country. Additionally, Argento later accused the Pulitzer Prize-winning Farrow of writing a “simplification that ruined my life.”

At his 2020 trial in New York for sexual crimes, witnesses described Weinstein as being genitally malformed, as subjecting them to the foulest verbal abuse, even as smelling of excrement.

Weinstein was evil, but not stupid. As a rapist, he understood that if he administered a multitude of humiliations and degradations on top of the shock of violation, his victims would be less likely to speak out. As a source of patronage in the famously narcissistic and ruthless field of show business, he believed that most actors and actresses have no real sense of self and will do anything to get famous. They can even be persuaded to think of their own violation as a kind of investment in their career.

Bourdain became, by Argento’s own admission, her protector, her champion, a second or third father to her two children. Photographs of the couple show them to be deeply in love. He gave her work on Parts Unknown. He became an ardent champion of #MeToo, as it turned its attention to the restaurant industry. One casualty of this inquiry was Bourdain’s longtime friendship with Mario Batali, who was accused of, among other things, drugging and raping several women. “Any admiration I have expressed in the past for Mario Batali . . . is, in light of these charges, irrelevant.” Bourdain admitted also to being sickened and feeling guilty for his own complicity in the restaurant business’s “meathead culture.”

In August 2018, a month after Bourdain’s suicide, the New York Times ran an article titled “Asia Argento, a #MeToo Leader, Made a Deal With Her Own Accuser.” According to the article, Argento had arranged a payment of $380,000 to an actor named Jimmy Bennett. Bennett had claimed that he and Argento had had sex when he was 17, in a hotel room in the state of California, where the age of consent is 18. Furthermore, she had taken several postcoital selfies, which he had offered to return on condition that she pay him the money.

The Times also revealed that Argento and Bennett had first met when he was 8 and he played her son in a movie. After the movie ended, they had continued to keep in touch, and had a quasi-mother-son relationship, calling each other ‘‘Momma” and ‘‘Son.”

The next day, Argento admitted that it been Bourdain, through a lawyer, who had paid Bennett the money.

Victim, opportunist, malefactor, hero—it was difficult to know what to think of Asia Argento; the Times didn’t quite know what to make of this story, but the Italian tabloids responded with the inevitable headline, “Asia Weinstein.’’

Ronald Sukenick would have understood Argento right away: she was a familiar type of Bohemian Bad Girl, one who delights in deliberately breaking taboos.

It’s hard not to conclude that in Argento, Bourdain had gotten exactly what he thought he wanted.

There are two main fears that an older, successful man has about a relationship with a younger woman: the first is that he will be made to look publicly foolish; the second is that she will use him in a mercenary way. The TMZ photographs, appearing seven months after he had made the massive payment to her blackmailer, seemed to confirm both of these fears.

“In fame, there is injury to one’s sense of rebellion,” wrote John Berryman. But here, in the whole Argento affair, was an existential assault on Bourdain’s dignity as well.

$380,000 is a lot of money, even for someone who is supposed to be rich. It’s enough to pay for a daughter’s college, a daughter’s wedding and a daughter’s honeymoon.

It’s also possible that Bourdain, whom most of his crew described at the time as wearying of the job that he once described as the best in the world and wanting only to “get the shot” so he could go back to the hotel, now felt trapped. And realized that he was out of reach of all except the most extreme and irreversible forms of self-soothing.

Bourdain was his mother’s boy—far too decent to encourage the psychopath in himself to harm the people around him, but not grounded enough to discourage that psychopath from turning his energies against himself.

After he died, Rose McGowan, who had been a friend to both Argento and Bourdain, described them as having a “free relationship, they loved without borders of traditional relationships . . .” The trouble with a free relationship, practically speaking, was that it meant you were faithful when you felt like it and inconstant when you didn’t.

A few weeks after Bourdain died, Argento posted a sad-looking picture of herself, with the caption, “Life’s a Bitch. Then You Die.” It was near-autistic in its emotional tone-deafness.

The glamour of death or the banality of survival: Which is it going to be? —Rachel Kushner

Let’s say that suicide is a hate crime inflicted upon the self. It is motivated by hate because it aims to destroy something—the self—that cannot be abided. And it is a crime because . . . why is it a crime? Nowadays, the idea that suicide is a crime would attract a lot of furious pushback, but if you had asked a random sampling of Americans in say, 1950, they might have said, “Because your life does not belong to you alone. It belongs to God or your fellow congregants or your country or your family.”

As prohibitions, legal and moral, have receded, the medicalized explanation for suicide has grown in prominence, and rates of suicide have risen dramatically.

Perhaps there is a reason for this: suicide is the ultimate expression of our cult of the individual. Maybe the ultimate expression of individualism is not to get a Maori face tattoo, or to change your name from Katherine to Clover or even Keith, or to do an interpretive dance in the middle of a supermarket just because you feel like it. Maybe it is to kill yourself. Could it be that suicide is, as Chesterton suggested, the consummate act of Luciferian arrogance:

Not only is suicide a sin, it is the sin. It is the ultimate and absolute evil, the refusal to take an interest in existence; the refusal to take the oath of loyalty to life. The man who kills a man, kills a man. The man who kills himself, kills all men; as far as he is concerned he wipes out the world.

An eloquent statement of the old-school view of suicide was on display from an unlikely figure, in an episode of the Joe Rogan Podcast made shortly after Bourdain’s death.

Bourdain had so many friends that you need classify them by type to keep them straight. There were chef friends and writer friends and TV friends and movie friends and MMA friends and regular-guy friends and musician friends and graphic artist friends. David Choe was a graphic artist friend, responsible for a striking Francis Bacon-influenced portrait of Bourdain. After Bourdain killed himself, Choe posted on Twitter: ‘‘RIP tony I love you…fuck you’’

Choe’s rise-to-success story was one that every creative figure dreamed about. He had painted a series of murals for an upstart company called Facebook and had received stock in lieu of a cash payment. He had sold the stock for hundreds of millions of dollars. And then had fallen prey to the contemporary malady: too much freedom. He had developed, by his own admission, a drug problem, an alcohol problem, a prostitute problem, even an eating disorder.