by Kenneth Francis (July 2020)

What makes a great film? Besides atmospheric cinematography and excellent acting, one of the crucial aspects of movie-making is good dialogue that complements well-crafted scenes. That is why so many moviegoers always remember a favourite scene with such *lines, often misquoted, while 95% of the story won’t be quoted: *(Goodfellas: “Funny, how?” Midnight Cowboy: “I’m walkin’ here!”

In recent years, good dialogue has been ruined by pretentious, cliché-ridden, over-stated lines; delivered with millennial, vocal-fry Kardashian croaks, with an uptalk intonation at the end of each sentence, while navel-gazing, ‘dark’ piano/violin tunes accompany maudlin, saccharine scenes.

This new-wave of Hollywood airheads, think that by mumbling like Brando, their neo-Method acting skills will receive rave reviews, especially if they look into the camera and tell the viewer they’re “struggling” with their “inner demons” (inner clichés more like it). And there’s always a shallow, virtue-signalling reviewer and fanbase that’ll grant them their wish, especially if the dialogue message has the ubiquitous indoctrination propaganda of anti-Christian social engineering.

So, what else is it that makes good dialogue in a film? For me, good dialogue is like great poetry where the real meaning can sometimes be hidden or disguised beneath the words. It should also avoid being pretentious when pondering on the meaning of life and the suffering we face during our daily struggles. Below are my Top 10.

The Body Snatcher (1945), directed by Robert Wise, is based on a story by Robert Louis Stevenson, and screen-written by Phillip MacDonald.

This little movie gem from the 1940s is quite wicked and darkly complemented with eerie, foggy night street scenes, albeit studio-staged, of early-19th century Edinburgh. In this scene below, a grave-robber named John Gray (Boris Karloff) walks into a local inn where the doctor he supplies bodies to, ‘Toddy’ MacFarlane (Henry Daniell) is at a table having a drink. Gray, who recognises his own evil deeds, starts to taunt MacFarlane and his lack of knowledge of consciousness and the soul.

INTERIOR. AN INN. EDINBURGH CITY. NIGHT.

(GRAY approaches MACFARLANE sitting at a table and sits down beside him. During the conversation, GRAY turns aggressive, taunting MACFARLANE and telling him he’s no doctor, as MACFARLANE tries to defend himself)

Edited:

MACFARLANE

…I am a doctor. I teach medicine.

GRAY

Like Knox taught you? Like I taught you? In cellars and graveyards? Did Knox teach you what makes the blood flow?

MACFARLANE

The heart pumps it.

GRAY

Did he tell you how thoughts come and how they go and why things are remembered and forgot?

MACFARLANE

The nerve centers – the brain.

GRAY

But what makes a thought start?

MACFARLANE

(fuzzily)

In the brain, I tell you. I know.

GRAY

You don’t know and you’ll never know or understand, Toddy. Not from me or from Knox would you learn those things. Look – He points to a mirror behind MacFarlane’s head.

GRAY (CONT’D)

Look at yourself, Toddy, could you be a doctor – a healing man – with the things those eyes have seen? There’s a lot of knowledge in those eyes, but there’s no understanding. You’d not get that from me.

Tokyo Story (1953), directed by Yasujiro Ozu and written by Ozu and Kogo Noda.

I regard this masterpiece as the greatest film of all time. What’s remarkable about Tokyo Story is its universal appeal and simplicity, despite some critics at the time of its release saying it was ‘too Japanese’. Also, its timeless themes of the disappointments of family life in a fallen world are spot on and not preachy. What makes the dialogue good is it’s more suggestive than bluntly stated, thus it’s void of over-sentimentality or emotive schmaltz.

Many of Ozu’s camera shots are at the eye level of a Japanese person seated on a tatami mat, a low camera position with limited movement that works quite well, as the viewers feel like they’re sitting in the room with the characters. I also find it difficult to watch this film without feeling quite sad.

As for the plot: it’s almost void of any but concentrates more on the subtle existential familial plight of humans, as a retired Japanese couple travel to Tokyo city to visit their adult children (son, daughter and widowed daughter-in-law) and grandchildren. The couple, a kind of ageing Jack Sprat and his plain-looking, plump wife, discover that their children are preoccupied with their own busy lives and seem to be irritated by the visit and reluctant to take their parents anywhere.

This is quite unsettling but beautifully executed. Many of us have been irritated by the ‘inconvenience’ of those who gave their lives to loving and rearing us from the cradle. (Johnathan Swift said satire is a sort of glass, wherein beholders do generally discover everybody’s face but their own; similarly, Tokyo Story is a mirror we gaze at, and fail to see our deeply flawed selves, despite lamenting, either consciously or intuitively, we could’ve been better children to our parents.)

Later in the story, the elderly couple return home and the grandmother dies, thus the children prepare a journey for the funeral. Had this been a Hollywood movie, it would’ve drowned in a sea of treacle and sugar. But Ozu, fortunately lacking slick, technical cinematic movie skills, is deeply reflective and philosophical. Even the simplistic black-and-white visuals of exterior shots of deserted streets, industrial landscapes and trains, are simply shot in what I’ve come to regard as, ‘small cinema’. As for dialogue and facial expression: The masterstroke in this scene below is NORIKO’s smile, as she answers the last question.

EDITED EXTRACT:

INT. DAY. HOUSE. TWO WOMEN CHATTING.

KYOKO

[after the rest of the family had left] I think they should have stayed a bit longer.

NORIKO

But they’re busy.

KYOKO

They’re selfish. Demanding things and leaving like this.

NORIKO

They have their own affairs.

KYOKO

But you have yours too. They’re selfish.

NORIKO

But Kyoko…

NORIKO

But children become like that, gradually.

KYOKO

Then… you, too?

NORIKO

I may become like that in spite of myself.

KYOKO

Isn’t life disappointing?

NORIKO

(Smiling) Yes, it is.

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), directed by Stanley Kubrick; screenplay by Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke.

The only one with the best lines in this movie is a robot called Hal. Regarded as one of the most enigmatic films of all times, the story revolves around the evolution of humans and space travel in search of alien artefacts. During the space voyage, astronaut DAVE BOWMAN gets into a conversation with the AI computer, HAL.

INT. SPACE STATION. OUTERSPACE.

Edited extract:

HAL

By the way, do you mind if I ask you a personal question?

DAVE BOWMAN

No not at all.

HAL

Well, forgive me for being so inquisitive but during the past few weeks I’ve wondered whether you might have some second thoughts about the mission.

DAVE BOWMAN

How do you mean?

HAL

[…] Well, certainly no one could have been unaware of the very strange stories floating around before we left. Rumours about something being dug up on the Moon. I never gave these stories much credence, but particularly in view of some of other things that have happened, I find them difficult to put out of my mind. For instance, the way all our preparations were kept under such tight security. And the melodramatic touch of putting Drs. Hunter, Kimball and Kaminsky aboard already in hibernation, after four months of training on their own.

DAVE BOWMAN

You’re working up your crew psychology report?

HAL

[pausing for a few seconds] Of course I am…

Midnight Cowboy (1969), directed by John Schlesinger; writers: Waldo Salt (screenplay), James Leo Herlihy. Stars: Dustin Hoffman, Jon Voight

This movie is based in New York City at the end of the 1960s, a decade of profound sexual, social upheaval and technological changes. On the busy Fifth Avenue street during daytime, as crowds walk the pavement outside Tiffany’s & Co., a well-dressed man lies motionless, face down on the sidewalk footpath as the pedestrians walk around him, avoiding him. Joe Buck, a naïve, tall blond Texan new to the city, looks on in confusion.

Buck had quit his job as a dishwasher down south and arrived in the Big Apple in search of work as a stud. At night, joe strolls past the long line of cinemas on 42nd Street featuring peepshows and X-rated porn movies where the hustlers, pimps and hookers hang out.

He soon meets Enrico Salvatore “Ratso” Rizzo, a scruffy rogue with a gammy leg, whose most-quoted line for moviegoers is, “I’m walkin’ here!” as he’s nearly run over by a car. For $20, Ratso manages to con Joe by leading him to an all-to-familiar, Hollywood de rigueur crazy preacher called O’DANIEL, who is also a pimp, ostensibly gay, theologically illiterate, and a lunatic who worships Christianity in a distorted, fanatical way; such crazy people unwittingly smear and scandalise followers of Christ.

Had he been normal and someone who understood Christianity, his character could’ve saved Joe from a life of fornication and ruination, but that wouldn’t make the movie great. Instead, he scares him off. In this scene below, we see how this unfolds, as Ratso leads Joe to O’DANIEL’S hotel room before fleeing down the lift.

INT. WEST SIDE HOTEL CORRIDOR – NEW YORK CITY – DUSK.

Joe finds 901 at a dark end of the corridor, knocks confidently, then the door is thrown open by O’DANIEL, who is wearing an old bathrobe.

O’DANIEL (a chubby man in his late fifties with the face of an owl)

You must be Joe Buck. Come in.(He examines JOE, who tells him, “I’m a first-class stud)

Edited:

O’DANIEL

…Seems to me you’re different than a lotta boys that come to me. Most of ’em seem troubled, confused, but I’d say you knew exactly what you want.

JOE

You bet I do, sir.

O’DANIEL

But I’ll bet you got one thing in common with them other boys. I’ll bet you’re lonesome.

JOE

Well, not too, I mean, a little.

(O’Daniel rises suddenly in a fury of self-righteousness, pacing, his voice simpering, whining sarcastically.)

O’DANIEL

I’m lonesome. I’m lonesome so I’m a drunk. I’m lonesome so I’m a dope fiend. I’m lonesome so I’m a thief, a fornicator, a whore-monger. Poop, I say, poop! I’ve heard it all and I’m sick of it, sick to death.

JOE

Yessir, I can see that…

The Last Picture Show (1971) is directed and co-written by Peter Bogdanovich and Larry McMurtry. The story is set in a small town in Texas, USA, at the beginning of the 1950s.

Although a Hollywood production, the scene I’ve selected is more sophisticated arthouse than Tinseltown tripe, thus it would not be a favourite for the typical, popcorn movie-goer who thinks Tom Hanks is the greatest actor of all time.

In fact, the following dialogue might even seem quite bland. But, like the scene/dialogue in Tokyo Story, it is the seemingly bland conversation that makes it so special. The scene features a monologue from ‘Sam the Lion’ (Ben Johnson), the town’s elder wise ‘old’ man: well-respected and polite, he’s a typical gentleman endowed with kindness and fairness. Here, alongside high-school senior, Sonny (Timothy Bottoms), he sits by a lake reminiscing on the past when he brought a young lady swimming on the lake over 20 years ago.

SAM THE LION

I just come out here to get a little scenery. Too pretty a day to spend in town. You wouldn’t believe how this country’s changed. First time I seen it, there wasn’t a mesquite tree on it. Or, a prickly pear neither. I used to own this land, you know. First time I watered a horse at this tank was more than 40 years ago. I reckon the reason why I always drag you out here is probably l’m as sentimental as the next feller when it comes to old times. Old times. I brought a young lady swimming out here once – more than 20 years ago. It was after my wife had lost her mind. And my boys was dead. Me and this young lady was pretty wild, I guess. In pretty deep. We used to come out here on horseback and go swimmin’ without no bathin’ suits. One day she wanted to swim the horses across this tank. Kind of a crazy thing to do, but we done it anyway. She bet me a silver dollar she could beat me across. She did. This old horse I was riding didn’t want to take the water. But she was always looking for somethin’ to do like that. Somethin’ wild. I bet she’s still got that silver dollar.

Fat City (1972), directed by John Huston; screenplay/novel: Leonard Gardner

Fat City is a small film with ordinary everyday characters that works magnificently. Some of the dialogue in the scene I’ve selected below contains the odd movie cliché but it actually works. The plot is straightforward: Billy Tully, a thirtysomething boxer who works as a fruit-picker, attends a gym in Stockton, California. Here he meets 18-year-old Ernie Munger and both men spar with each other. Tully is impressed with Munger and tells him to look up his old training coach, Ruben. Despite Tully’s life being in ruins due to heavy drinking and failed relationships, he starts training again to enter the ring for a big fight. Outside of the boxing world, he meets alcoholic Oma, a woman aged in her late thirties, in a downtown, ‘last-chance-salon’-type bar. After a second meeting in a bar, Tully approaches Oma, who sits alone drinking at the counter. They argue a bit, then Tully tries to make it up with her.

INT. BAR. DAY

Edited:

TULLY

Listen. Let me tell you something. You can count on me. Right down the line…

OMA

[…]These others, I wouldn’t ask the time of day.

TULLY

They wouldn’t give it to you.

OMA

You know something? You’re the only sonofabitch worth shit in this place.

TULLY [contemplating the paradoxical insult/compliment]

I appreciate that. I mean, because there is something I really like about you.

OMA

I like you, too.

TULLY

(Raising his glass) To us.

OMA

Let’s get out of this joint.

TULLY

Let’s go somewhere else.

Outside the bar, as they start to walk home, Oma begins to cry. She says to Tully, “I love you”. It’s then that the viewer suspects the doomed couple are entering the gates of alcoholic hell.

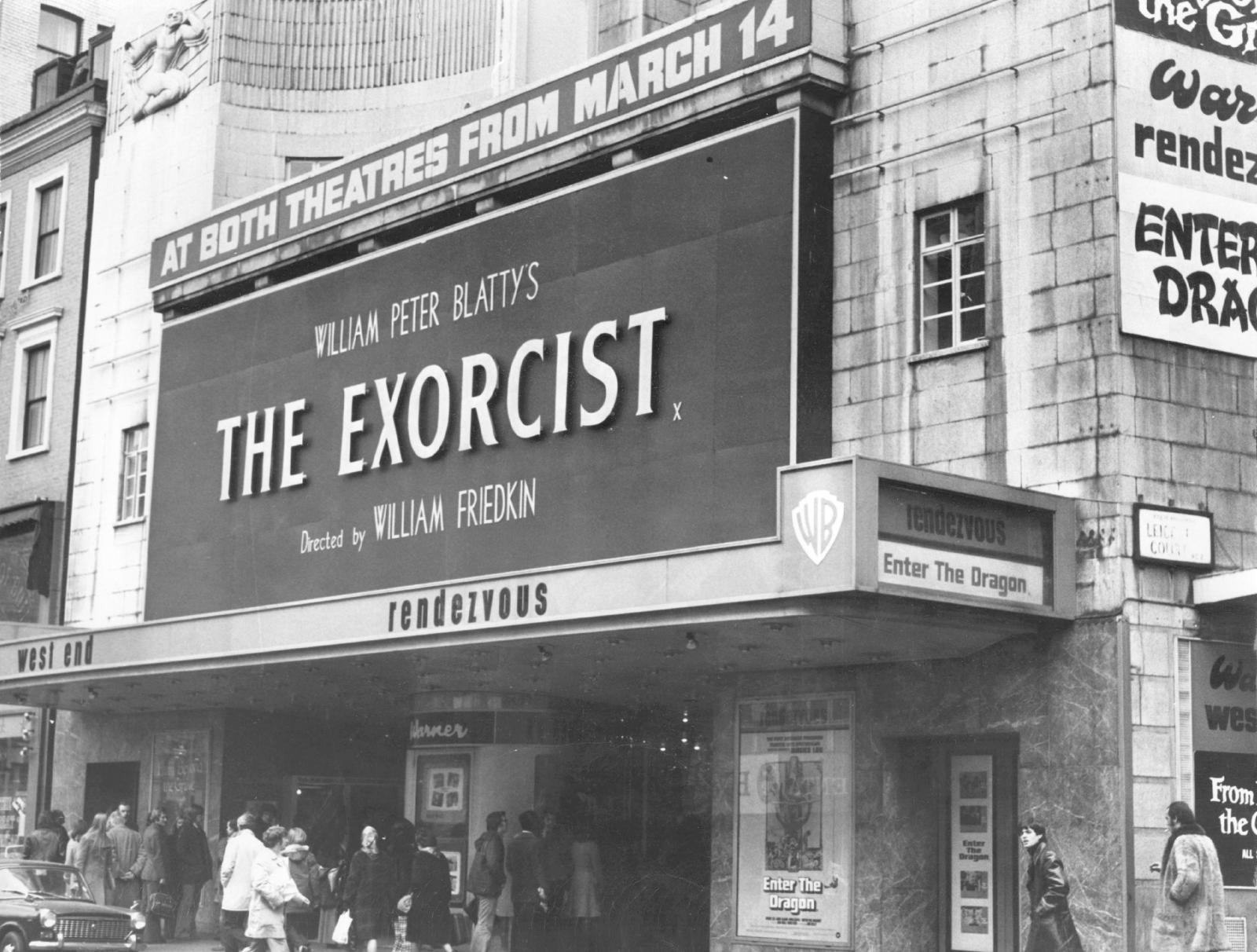

The Exorcist (1973), directed by William Friedkin and written by William Peter Blatty, is based in the Washington DC area during Watergate.

There are a few flaws in this film, some of which are the dated special effects and bad make-up, but, nonetheless, it remains a masterpiece when it’s screened without the vulgar use of the crucifix as a sex toy and the desecrated statue of the Virgin Mary scenes.

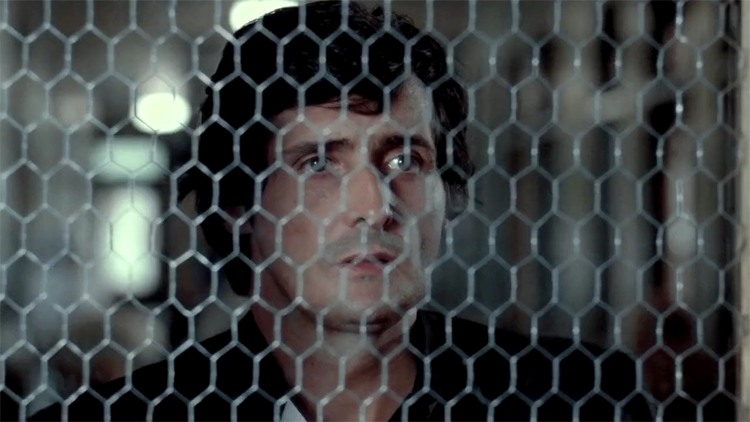

Besides the possessed girl in the story, the main character is Fr Damien Karras, a thirtysomething Jesuit psychiatrist. After visiting his elderly mother, who lives all alone in a New York City ghetto and later dies, Fr Karras suffers a loss of faith. What attracts me to this particular scene are the simplicity and seemingly mundane dialogue. In fact, the profound existential message from the dialogue is the cause of most of the world’s sorrows.

For those who no longer believe in Christ, Fr Karras is quite the ideal metaphor for existential despair, when spiritual crisis is “more than psychiatry”. Here, Karras enters a music-filled, lively bar full of students in the campus of Georgetown University, a hotbed for Jesuitical theology, a watered-down version of True Scripture. Walking away from the bar with two beers, Karras sits at a table in a dark partitioned area and puts one beer in front of the president of the university, Fr Tom, a tall, slim, elderly man.

Int. College Campus Bar. Night.

KARRAS

It’s my mother Tom. She’s alone, I never should have left her. At least in New York, I’d be nearer, I’d be closer.

PRESIDENT

Could see about a transfer Damien.

KARRAS

I need reassignment, Tom, I want out of this job. It’s wrong, it’s no good.

PRESIDENT

You’re the best we’ve got.

KARRAS

Am I really? It’s more than psychiatry and you know that, Tom; some of their problems come down to faith, their vocation, the meaning of their lives and I can’t cut it anymore. I need out, I’m unfit. I think I’ve lost my faith, Tom.

Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975), directed by Terry Gilliam and Terry Jones; writers: Graham Chapman and John Cleese.

Based in England around AD 500, this wonderfully deranged movie has some excellent literary lines from King Arthur that would even make the Bard chuckle from his grave. However, it is not for those with a surrealism deficiency. When one hears lines like the following below, then there is certainly an absurd narrative afoot: A giant knight, with a dark hairy body, address King Arthur, as he comes to a halt deep in the woods:

KNIGHT, who used to say ‘Ni’

We are no longer the knights who say Ni! We are now the knights who say ekki-ekki-ekki-pitang-zoom-boing!

As whacky as that scene is, I’ve instead chosen the scene when King Arthur arrives at a castle, trotting on an imaginary horse with his servant, Patsy, trotting behind him, banging to coconuts together for sound effect of a horse’s hooves. Some peasants at the scene are gathering dung. Dennis the Peasant, who is beside a peasant woman, asks Arthur who he is, to which Arthur replies, “I am your king”. The PEASANT WOMAN then asks him, “How’d you become king?”:

King Arthur

[Dramatic, brief monologue, accompanied by angelic music]: The Lady of the Lake, her arm clad in the purest shimmering samite, held aloft Excalibur from the bosom of the water, signifying by divine providence that I, Arthur, was to carry Excalibur. That is why I am your king.

Dennis the Peasant

Listen. Strange women lying in ponds distributing swords is no basis for a system of government. Supreme executive power derives from a mandate from the masses, not from some farcical aquatic ceremony.

Arthur

Be quiet!

Dennis the Peasant

You can’t expect to wield supreme power just ’cause some watery tart threw a sword at you! I mean, if I went ’round saying I was an emperor, just because some moistened bint had lobbed a scimitar at me, they’d put me away!

Goodfellas (1990), directed by Martin Scorsese; writer: Nicholas Pileggi, who wrote both the book and screenplay.

The actor Charles Laughton once said that “Method actors give you a photograph”, while “real actors give you an oil painting.” I would say the same thing about the movies The Godfather and Goodfellas: the former is like an oil painting while the latter is more a photograph. But like photographs, sometimes the picture can often lie. In this scene below, gangster Tommy DeVito lies to his buddy, Henry, when he pretends to be offended and confused when called a ‘funny guy’. Surrounded by a group of fellow gangsters during the1960s, both men are drinking and having a laugh which comes to an abrupt end when Henry tells Tommy he’s funny.

INT. RESTAURANT. NIGHT.

Extract:

HENRY HILL

Just… ya know… you’re funny.

TOMMY DE VITO

You mean, let me understand this cause, ya know maybe it’s me, I’m a little fucked up maybe, but I’m funny how, I mean funny like I’m a clown, I amuse you? I make you laugh, I’m here to fuckin’ amuse you? What do you mean funny, funny how? How am I funny?

HENRY HILL

Just… you know, how you tell the story, what?

TOMMY DE VITO

No, no, I don’t know, you said it. How do I know? You said I’m funny. How the fuck am I funny, what the fuck is so funny about me? Tell me, tell me what’s funny!

HENRY HILL

[long pause] Get the fuck out of here, Tommy!

TOMMY DE VITO

[everyone laughs] Ya motherfucker! I almost had him, I almost had him. Ya stuttering prick ya. Frankie, was he shaking? I wonder about you sometimes, Henry. You may fold under questioning.

Naked (1993) Director/writer Mike Leigh

This impressive, bleak film appears to me to be metaphorically directed with a sledgehammer dipped in coagulated sewage. And the blue-grey cinemaphotography gives it a cold, gritty, raw feel. But despite the heavy-handedness of the narrative, the film works quite well and is arguably one of the best movies of the 1990s, if not the best.

The story revolves around a degenerate misfit ‘philosopher’ called Johnny Fletcher (played by David Thewlis), resembling a modern-day Catweazle, and his debauched travels in a Godless, amoral UK (to be fair, these adjectives also apply to the entire anti-West).

After a rough sexual encounter copulating with a woman in a Manchester alleyway which looks like rape, Fletcher steals a car and goes on a sleazeball odyssey to London. During his travels, he meets Brian, a security guard, who has to contend with the preaching of Fletcher’s pessimistic world view on the doomed fate of humanity. I regard this scene as the greatest of all Leigh’s films.

INT. BUILDING. LONDON. NIGHT

JOHNNY

[…] Take a look around you man, it’s all breaking up. Are you not familiar with the book of Revelations of St. John, the final book of the Bible prophesying the apocalypse?… He forced everyone to receive a mark on his right hand or on his forehead so that no one shall be able to buy or sell unless he has the mark, which is the name of the beast, or the number of his name, and the number of the beast is 6-6-6… What can such a specific prophecy mean? What is the mark? Well the mark, Brian, is the barcode, the ubiquitous barcode that you’ll find on every bog roll and packet of johnnies and every poxy pork pie, and every fuckin’ barcode is divided into two parts by three markers, and those three markers are always represented by the number 6. 6-6-6! Now what does it say? No one shall be able to buy or sell without that mark… They’re going to subcutaneously laser tattoo that mark onto your right hand, or onto your forehead. They’re going to replace plastic with flesh. Fact!

These are just some of the best lines in modern cinema history. Some other movies that are favourites of mine that I left out but I highly recommend, are: CasablancaGreat Expectations (1946 version)

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

__________________________________

Kenneth Francis is a Contributing Editor at New English Review. For the past 20 years, he has worked as an editor in various publications, as well as a university lecturer in journalism. He also holds an MA in Theology and is the author of The Little Book of God, Mind, Cosmos and Truth (St Pauls Publishing) and, most recently, The Terror of Existence: From Ecclesiastes to Theatre of the Absurd (with Theodore Dalrymple).

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link