Excerpt from the forthcoming Stones of Contention on New English Review Press.

by Timothy H. Ives

It may be helpful to understand the key assumptions that guide my writing and analysis, the first of which is my unsophisticated approach toward history. History aims to reconstruct events, trends, and patterns that occurred in a past that are real and irrevocable, regardless of whether that past is four centuries, years, or minutes old. And I see the rhetorical question “Who owns the past?” so frequently used by humanities and social science professors to provoke classroom discussions as needlessly and erroneously planting the idea that a living group of people could “own the past.” Surely, any such claim should be taken no more seriously than the cast of Sesame Street should they claim to “own the alphabet.” Nobody “owns” history either, though individuals may hold copyrights to the versions they produce. History is a fact-based system of knowledge that is of great interest to humanity at large, the lessons and meanings of which are conveyed through interpretive contexts that rank probabilities, even boring or ugly ones, above possibilities.

But the theoretical impossibility of getting history completely right does not justify abandoning all attempts. Nobody is entitled to a history that makes them feel good about themselves or the groups to which they belong. History is too important to sacrifice on the altar of identity because it offers an extensive record of how people succeeded or failed in the past, how some ideas light the way to prosperity and growth, and how others usher in oppression and societal collapse. History matters because the human story is complicated and full of suffering—it always has been—and we could use reliable information to mitigate this condition as best we can, to identify past mistakes and avoid their repetition.

But the prevailing vision of history, as an egalitarian pageant of equally valid, self-authenticating “perspectives” on the past representing the “voices” of particular groups, is dangerous to society at large. It reserves a special place for everyone, which is exciting news for political extremists, con-artists, and megalomaniacs eager to register their self-interested propaganda as legitimate contributions to a ”broader perspective” of history. The mainstreaming of postmodern relativist thought and the advent of internet culture have proven a perilous combination, expanding space for any number of disconcerting ”historical perspectives” to flourish, including Holocaust denialism among young, far-right activists on an international scale (Busby 2019; Muhall 2018) and neo-Confederate Civil War revisionism among Americans (Hadavas 2020). Information about the past, recent or distant, needs to be handled responsibly because it is in the collective interest.

In writing this book, I have not conducted a single interview, and presume that I missed out on some useful information. But, ultimately, I saw relatively limited value in discovering what people choose to say about a racially charged topic, knowing that it might end up in a book, and was turned off by the prospect of engaging potentially hostile informants. I decided that my time on this topic would be more efficiently invested drawing upon the already ample public record of people’s words and deeds. Surely, that I have not consulted contemporary Indians in writing this will raise eyebrows among scholars who intimate that studying Indian pasts without formally affording some group of descendants some measure of control over the process is passé, if not unethical. Though a local collaborative archaeologist’s rhetoric of pursuing archaeology “with, for, of, and by Indigenous people” (Silliman 2020) may sound “progressive,” I prefer to emphasize that any individual, regardless of their race or ancestry, is capable of independently studying the pasts and presents of groups to which they do not belong and producing useful insights.

I also presume there are no solutions to complex social issues such as racial conflict, which is a major focus area of this book. Any serious student of American history learns that race relations are never “resolved.” They are negotiated though tradeoffs among and between a diversity of rational, self-interested actors within ever-shifting fields of opportunities and constraints, from one generation to the next. Those flirting with the idea that our generation might be the one to end racism have a tremendous hubris, an ignorance of the complexities involved, and a tragically flawed imagination of the phenomenon as a metaphysical substance to be “stamped out” rather than an ever-present complex of observable behaviors throughout multicultural societies that inflates or deflates according to circumstances.

Also, I insist that far too many New Englanders, both white and Indian, are clinging to some backward notions about Indians that run counter to social progress. Foremost is the popular tendency to romanticize Indians, which undermines their histories and deprives them of their full humanity in the present. This romanticism, a direct and ongoing legacy of colonialism—a projection of Indians that is only available through the settler colonial lens—lends buoyancy to their presumed innocence, moral integrity, and wisdom. As flatteringly attractive as this projection may appear, it is socially pathological because it “isolates them from rational thought, giving an unrealistic assessment of their abilities and place in the world” (Widdowson and Howard 2008:47). As one archaeologist soberly noted, assuming that “Native peoples are unencumbered by convenience, circumstance, political expediency, or gain” is not realistic (Starna 2017:133). While most Indian identity bearers claiming to seek ”peace, balance, and harmony” probably mean it, anyone who doubts that a few actually mean “wealth, territory, and power” suffers from a denial of basic human tendencies.

Fancying Indians as eternal victims of Western society not only denies them equal measures of agency in the past and social responsibility in the present, it also serves as a distraction from (and, by extension, an enabling mechanism for) painful aspects of life in Indian Country. For example, Indians are just as capable of, and often much better positioned for, victimizing fellow Indians than are cultural outsiders. To cite some comparatively benign examples, the temptation to illegally appropriate tribal funds has proven irresistible to a former Sachem (Norwich Bulletin 2016), a former Tribal Director of Housing (Mulvaney 2013), and a former Tribal Chairman (Contreras 2009). I do not air these facts to demonize these individuals. I do so to drive home the point that Indians fully qualify as ordinary people, burdened with all of the familiar shortcomings, temptations, and weaknesses that challenge humanity at large. But their ordinariness goes even further. They drive cars, speak English, own smartphones, go shopping, take out the trash, and pay taxes. And though some change into deer hide and ribbon shirts for certain events, this does not qualify them as any less modern, or any more ancient, than anybody else.

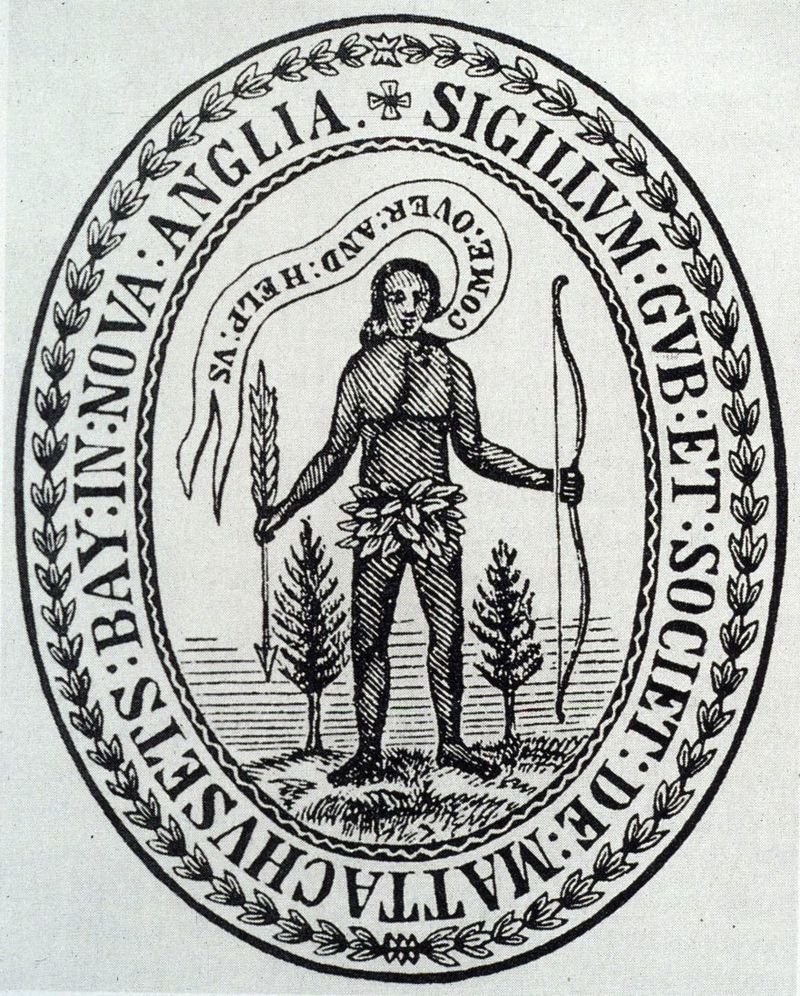

For some readers, a difficult pill to swallow will be my insistence that the centuries-old belief that New England’s Indians need intervention from deep-thinking, well-intentioned outsiders in order to thrive is as antithetical to their well-being now as it was when Puritan missionaries first arrived. Today, white New Englanders who see themselves as advocates for local Indians seem as uninterested as ever in considering just how messy and complicated their advocacy might be, or how easily negative effects can spread in the wake of good intentions. The remarkable idea of a privileged socioracial group benevolently lifting a less privileged one should always be met with remarkable skepticism. If this were so, when the Massachusetts Bay Colony put the words “Come Over and Help Us” in an Indian’s mouth (above), perhaps things would be different today.

In short, I am skeptical of individuals who go out of their way to broadcast their good intentions toward other groups of people at large. Self-concern would seem to be a universal human interest that is chronically under-disclosed though rarely underemployed. In regard to this apparent reality, I am aware of no racial or ethnic exceptions. So to any readers intending to brand this book anti-Indian, by all means enjoy your freedom to do so, but do not neglect to brand it as anti-white in equal measure to reflect my steadfast lack of racial preference.

As you must have already gathered, I am acutely tuned to the frequency of identity politics and am eager to lay bare its chronic ironies, hypocrisies, and absurdities, if only to leaven otherwise disheartening material. And though my prevailing “voice” may sound neo-conservative, know that I am a registered Democrat who has never voted for a Republican and never plans to, a member of the Unitarian Universalist Church, and a daytime fan of National Public Radio who unwinds to the commentaries of Trevor Noah and Stephen Colbert at night. I feel more inclined to criticize the political left than the right because I identify with the former as my tribe of origin, and have never stopped seeing its constituents as kinfolk with whom I can be bluntly honest. To me, the political right appears as a largely unexplored country inhabited by a pantheon of brilliant black scholars whose works do not “matter” to a left-leaning academy that chooses racial hypocrisy over intellectual diversity. Today, I tentatively identify as a radical centrist freshly committed to listening to the ideas of folks staked out on the political extremes without joining their crusades. Valuable ideas are routinely generated by people from across the entire political spectrum, and those ideas should be judged solely according to their own merits. And while certain ideas tend to fall into the orbits of certain identities, they are not bound to one another, nor are individuals bound to either. Internalizing this truth may unlock original, productive, and refreshingly unpredictable discourse that has become alien to the ideologically policed spheres of mainstream media and academia.

Regarding my modestly provocative writing style, I urge one demographic to be especially careful about how they respond—those readers who feel that my arguments are compelling. Resist any impulse toward uncritical embrace, especially if you are the type who is excited by the vision of a person strolling over a hornet’s nest wearing nothing but flip-flops. Read this book skeptically, appraise any or all of my sources, and question, challenge, or reject my conclusions as you see fit. You need not be an archaeologist, historian, or one of this book’s many featured self-declared stone structure experts to do this. You need only be a free and independent thinker. As someone who has spent a good deal of his adult life seeking and sharing knowledge within classrooms, I have always found the most practical, valuable, and liberating educational experiences without them. And I have tossed the bedazzled straightjacket of cultural relativism into the academic lost-and-found box so that I may more effectively leverage the most “disruptive” force known to our aspiring leftist shepherds—common sense. Common sense is that underappreciated little something that most New Englanders use to get by in their daily lives, that makes it possible for our multicultural society to function as a relatively integrated and navigable whole.

Walking a politically contentious line, I have taken care not to break explicit personal confidences or disclose restricted data, including tribal information that is protected under Section 304 of the National Historic Preservation Act. And though I take the liberty of sharing an assortment of anecdotes and stories drawn from my personal interactions with various people over the years, I have, in accordance with the conventions of personal memoir, stripped them of identities and omit key circumstantial details to ensure adequate protection for the guilty. Regardless of whether or not the COVID-19 pandemic has abated by the time this book is published, I imagine that I will enjoy a special envelope of social distancing in many settings for years to come. I suppose I would rather have my reputation flogged by people who never actually read this book than feel complicit in a silence with far-reaching negative implications for society at large.

And, ultimately, that is why I wrote this book. I felt compelled by a deep-seated fear of loss, the kind many Americans experience whenever they read the news or engage social media. I fear that when enough people rally to the identitarian visions of their choice, and when enough of the remaining population becomes too afraid to openly engage them with honesty and reason, the democracy which otherwise maintains a space for both, will collapse. Lloyd Wilcox, the late Medicine Man of the Narragansett Indian Tribe, once said: “Representative democracy is the finest thing I have ever examined as far as the government’s concerned” (Burns et al. 1979). I agree with his statement and will stand behind it to the last.

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link