by Justin Wong (April 2022)

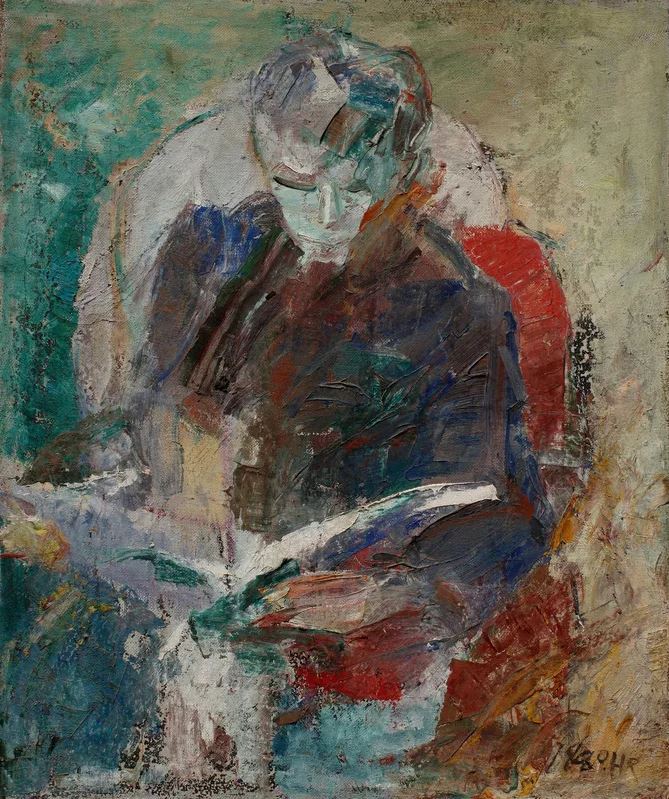

Man Reading, Huang Rui, 1980

Henry was a pastor of a church in a small village neighbouring a thriving city. He had few duties in regards to his job, he went to meetings with Church bodies, prepared his sermons, and preached on Sunday mornings to a meagre congregation, only a few disciples made-up his ministry. The town being a relatively small place, there were few in his community, he had much free time to deal with matters that weren’t duties of the church. He had been married for some thirty years, to someone who stuck beside him through better and worse. Their marriage would have been blissful, except for their being childless. Despite their being more than genial, there was a void in their lives that would’ve been filled if they had children.

This being so – the hand they were dealt – there was no animosity between the two. They learnt not resent the other for not being blessed to raise children. This gave them free time for activities other than the rearing and raising of infants. Their void was filled with a closeness they developed with their nephew, Rory. He was near and dear to Henry; spending time with his uncle and aunt, the child slept over at theirs, usually for weekend length stays in his youth.

The child was his wife’s sisters. Henry could see more than a likeness with his wife, and the boy. In relation to the boy’s father and mother, there was a resemblance handed down by the two of them.

What joyed Henry about his seeing his nephew, was that he was getting through to him, this was particularly true of Rory’s younger years. In that period, Rory got a great deal of joy in going to church, Sunday School, hearing the sermons Henry delivered, attending prayer meetings. He took to Henry’s religion, holding its precepts and claims as self-evident. Henry thought this was through his sermonising, the way he taught, the substance of the gospel.

Henry was right to assume that he provided him a faith in the almighty, something that if true, would last him till the grave, – the blessed state of salvation. Entering into adolescence, questions began to seep into Rory’s mind in regards to Christianity. Doubts plagued him as a wasting disease. This was due to him being older, and transforming into a man. There was likely much discussion about these things at school. In this setting, he doubtless knew older boys whom he desired to impress. Embracing ideas to do with unbelief was the way to go about it. One’s teenage years are a period in life when people are liable to swallow preposterous claims about the world. In this time of life, the young fall victim to political idealism, anti-establishment ideas rooted in moral superiority. This railing against the system, one’s inherited institutions, has nothing to do with politics as it has to do with religion. It’s a way in which the young, on the cusp of their independence, wish to form an identity.

Henry suspected this when Rory questioned him about things that he took as gospel beforehand. One day he came up to him saying: “There are so many religions in the world, almost all of them conflict one another, how do we know that we have the right religion?”

It wasn’t an original criticism. It was a sophomoric question, so he gave a sophomoric answer:

“Well, there are many claims about many things. Once people assumed the sun went around the earth, and the Hindu’s believe the earth is placed on top of two elephants, who themselves are placed on top of an infinity of turtles. One doesn’t say that because there are all these claims about the shape and position of the Universe, that there is no way of knowing the truth. One rather uses their God-given gifts of reason to deduce the truth of things.”

Throughout his teenage years, a spirit of conflict arose in Rory’s breast. Henry was still fond of his nephew, they peaceably conversed, but there now was an enmity between them, there was confrontation where it once was complimentary. Rory brought up flaws with the Bible, with Christendom’s long past. Henry answered these questions as best as he could. He wasn’t sure his nephew was an avowed sceptic as yet, although he possessed many of the questioning traits, the contempt for tradition, the sanctimoniousness. Rory believed the Judeo-Christian tradition hindered man throughout the six or so Millenia since its inception.

This was until Rory read a novel, which he touted as opening his eyes. All his doubts now transformed to certainties.

Rory was so convinced that what he read was so true that it was a dangerous document, one that was liable, if read by the whole of humanity, to put a nail in the coffin of Religion. If all the clerics of the Island read it, this country would transform into a Secularist Utopia. From what Rory knew about the volume before him, the one he had in hand, was that it was published at the start of the nineteenth century. It was considered so contrary to the West, that it was banned temporarily, the church authorities denounced its author as a heretic. Rory’s reaction to the book probably said more about him, than about the book he claimed was so powerful as to wipe every veil of illusion from his eyes. For if everyone who read it was convinced of its ideas, if its arguments were so solid as to be irrefutable, why were men as his uncle in the world?

One day Rory went over to their house in the village on a Friday night. The surroundings were silent and still, seeing as they were stuck at the tail end of winter, darkness descended upon them at an earlier hour. People were winding down to a halt, from the contents of the hectic week. When Henry peered out of his window, he could spot cars zoom intermittently past, or he would catch the sight of people making their way to the village pub for a few drinks, through the now lamplit streets.

Henry wasn’t expecting to see his nephew that night, not that it was unusual for him to pop by announced, to talk, watch television, to stay the night. Although he arrived around their place that night without warning, and when Henry glimpsed him stood there, he had on his face, a look of devilish glee.

“Come in,” said Henry, figuring that he might catch a cold if he stood outside.

“I have something to show you,” said Rory, as if something happened to him, from which he couldn’t contain his joy, This concerned something characterising their relationship as of recent, argumentations as to the existence of God. “I recently read this novel, “The Adventures of Samuel Dunstable.””

“Oh, really,” said Henry, “I take it you enjoyed it, if you went all this way to tell me about it.”

“Yes, it is amazing, I am convinced that you would find it as enlightening as I did. I brought you my copy. It contains in it, terrific arguments against the existence of God. If you read it, you will come to the same conclusion as myself. Although this may make you hesitant to consume it.”

“Oh really, my faith is not so easily shaken. Reading a book is not going to change much.”

“Well read it then.”

“Ok, I will, anyway sit down, I’ll make for you a cup of tea, your aunt is going to prepare supper soon, I’ll tell her you’re here and to make extra.”

They spent the evening together, talking around the dinner table amongst themselves. After this, they retired to the living room and watched television. A gameshow came on, something they all enjoyed. He stayed the night in the guest room, a place reserved almost exclusively for him, as they rarely entertained others, aside from Rory. In the morning, Henry drove him back to the city, this worked out well, for he needed to go there for a few hours, to pick up some things from the shops.

He found his nephew infuriating, who although well-meaning, was growing more obnoxious as the years went forth. He put this drastic change to his adolescence, the teenage years, when one is liable to think that they know everything. Henry could hardly be too harsh on him, for he was once a teenager with all of the smugness this entails.

It didn’t much surprise him that if he was beginning to have doubts about the religion that Henry taught him, that he would read the novel, Samuel Dunstable. Although Henry had never read the novel, it was notorious in its free-thinking, and skepticism. These arguments weren’t as bothersome to Henry as his nephew assumed. He thought much like Jonathan Swift before him, one of the best arguments for the existence of religion, was atheism. If there was no religiosity and religious institutions, what else would skeptics turn their critical faculties towards? One can only be a vocal and avowed sceptic in Christian countries. Other cultures that aren’t Christian in make-up, don’t have the luxury of free-speech. Freedom of conscience is derived from Biblical exegesis. A culture that permitted a vocal substratum of atheist thought happened was an unintended consequence of Christianity. Although this kind of freedom was firmly rooted in the old faith.

He had a busy weekend set out for him, preaching his sermon on the Sunday, as well as evening prayers. He thought that he should keep his promise, and read the novel that so captivated his heart, and so convinced him of these vague doubts that began to creep, slowly in.

When Monday rolled around, Henry started the book. It was something he enjoyed reading in his free time, which were novels, particularly those of a specific time period – the nineteenth century.

The book starts with the titular character Samuel Dunstable who is born into relative prosperity and a strong unshakeable faith of the puritan variety. He finishes school and from there, makes his way in the world. In his early manhood we meet Samuel Dunstable as he is planning to go on journeys across England and Europe with his man Friday, Humphrey, where they get into a number of unfortunate scrapes along the way.

He and his friend are travelling through France, and when they happen to stay in a hostel, they are robbed by someone who takes all of their money. This infuriates them both, and interrupts their travels, leaving them penniless in the process. They try begging for bits of loose change from the locals, this was to little avail. They decided their best bet is to find work, at least to recuperate their losses. They find work on a vineyard, where they are expected to toil for twelve hours a day, picking grapes and doing other duties around the farm. This goes without saying, is hard and grueling labour. Samuel Dunstable manages to write to his loved ones, telling them of his predicament. It was in this instance, that he received a reply back from his beloved, she told him that she wished to call off their engagement, and that she is to marry another. This made the hero of the story overcome with melancholia.

The two friends soon realised they were being held captive on the vineyard by the vile owner, they found out that it was difficult for them to leave. The vineyard owner didn’t wish to lose any of his workers, who were difficult to come by. In the hush of night, when all was quiet, and no one was suspecting of it, they escaped the place of their imprisonment. They brought along all of the money they made, which wasn’t enough to allow them to sail back to England.

They eventually manage to leave France, and venture over to Spain. Samuel Dunstable is still love-sick, and starts drinking to get over his broken heart. In one of the bars, he meets a local girl named Maria, someone whom he gets close to, that he can see marrying, that would be an apt replacement for his duplicitous beau. She uses getting to know him, as a way of robbing him. She is working for a local gang of thieves that win the confidence of young men travelling through, with the promise of love, in order to rob their money. Coming out of a bar, Samuel and Humphrey are confronted with a group of slit throats, and from there, Maria reveals who she truly is, telling the bandits where their money is kept.

This leaves them back where they started, and they have to beg for money once again. They have nowhere to sleep, and spend their nights out under the stars, or if the weather was particularly unpleasant, in a stable, resting amongst sheep, cows, and goats.

This section of the book seemed to Henry to be concerned with the idea of Theodicy. Why a benevolent God lets bad things happen to seemingly good people. This may be a legitimate question, it has baffled the minds of many people. But there may be good reasons for things not panning out as one wishes. For Henry knew that a well-lived life is not one where all of one’s desires are fulfilled. Suffering may provide people with character, with wisdom, with empathy towards the oppressed. Although the novel then takes a surprising turn and from there, the narrative switches.

Samuel and Humphrey are desperate for money, they could decide to get another job working the fields, although they were not fond of having a repetition of their previous events, where they were captives to their employer. Humphrey thinks of a plan that would make them money quickly, and this was to go out into the town square of whatever village he was in, and get on top of a soapbox, and preach about an impending apocalypse. He makes up a threatening scenario, one that is caused by the greed and licentiousness of the populous. Humphrey said God was mad with them, and if they didn’t give up their ways and wealth, they were soon to meet a natural disaster. He said an earthquake would destroy their town, or that God will send locusts to blight their crop, so a famine will be upon them. Crowds were taken in by these talks, their preaching of fatalistic things. After these talks, Samuel passed around a collection plate, and begun to hoard the proceeds, which was a substantial amount of money. It was more than they could gain, merely begging, or being worked as mules in the fields. They made their way through different towns, and in each and every one, told the same stories, of the world soon coming to an end, of God angered with their sin as in days of Sodom. That they will reap their retribution if they didn’t mend their ways.

Going through with this scenario on multiple occasions they collected enough money to purchase their ride back home. This story has a bittersweet ending, both protagonists return to England. Although the implications were startling, both of the men going from devout Christians to non-believers in the process.

The tale is intended to show that religion is a ploy and made up to fill the pockets of those in positions of power. Samuel and Humphrey recuperate their losses by making up a story, that they used to dupe people with, to extract wealth from unsuspecting rubes. There is of course a history of this throughout the world, and in Christianity, but this says nothing about Christianity as much as the bombing of Dresden says about Britain. If everyone brought up the flaws of a particular entity, there would be no worthy people, institutions or nations.

Although there was another problem that Henry found with the book, something that his nephew probably didn’t pick up on.

Part 2

Henry thought that he would see his nephew at the weekend, this for nothing more than to see if he read the book, if he found a convincing rationale for a secularist worldview, within its pages.

He came around that evening, and when they saw each other, they commenced in small talk. He asked his nephew how his week was, what he learnt at school. Rory was hasty in his answers, blurting out brief utterances, answering Henry’s questions with least the syllables mustered from his lips. Rory wished to carry on his discussion from the previous week, the one concerning the novel he lent him, that he found so profound as to be life-transforming.

“So did you read it?” asked Rory, wishing to know his opinion, if it was a simulacrum of his own, if he was steadfast to his old beliefs.

“Yes, as it happens, I did,” said the vicar.

“So, what did you think about it?” asked his nephew eager to know.

“I found it to be incredibly convincing,” he said in a nonchalant way.

“What, so you agreed with what it says?” said his nephew wishing to know.

“Absolutely not,” said Henry, although he understood that he was perhaps being a little bit coy and playing a game with his nephew.

“But I thought you said that you found it to be convincing.”

“Oh yes, very. Let me put it like this, what is this?” said his Uncle as he pointed to a painting that was hung on the wall.

“Well, it is of a field, and there are trees, and there are flowers in the left-hand side, and what appears to be a group of children that are walking in the distance.”

“Perhaps that is one way of looking at it, but another way might be that it is a piece of wood around some paper, that is behind glass. You have described what it represents, and I have described its form.”

“I don’t understand what you’re saying.”

“I said I found the book to be convincing, though not of your ideas, the ideas that it is trying to convey, but rather of my own.”

“Really, I mean you just read that novel, and you found a rationale for Christianity.”

“Yes, I’ll explain, in the novel you have this idea that religion is something that is made up by people. That it can’t be true as it is something that is derived from the imagination.”

“Yes, that’s one of the points that it makes.”

“Well, that is a self-contradictory assertion. Either something that is of the imagination is by its nature false, which discredits itself in the process; Or things that are of the imagination can be true which credits its existence, but also gives credence to religion. Just as the moral relativist, wants you to not take seriously, any of his claims, then this novel wants me not to believe what it is saying. Such beliefs as you have begun to espouse are by their nature self-refuting. They are a form of intellectual self-mutilation. For if all made up things are untrue, then you will lose language, mathematics, culture along with the faith you despise. This is made of a desire to construct knowledge from out of an imperceptible world of truth, one inseparable from the divine, that is one and the same with God.”

“Are you saying that all imagined things are true, even when they are in direct contradiction.”

“No, it is in knowing the distinction between the imaginative and the imaginary, reality and unreality, truth as distinct from falsehood.”

Justin Wong is originally from Wembley, though at the moment is based in the West Midlands. He has been passionate about the English language and Literature since a young age. Previously, he lived in China working as an English teacher. His novel Millie’s Dream is available here.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link