by Albert Norton, Jr. (April 2023)

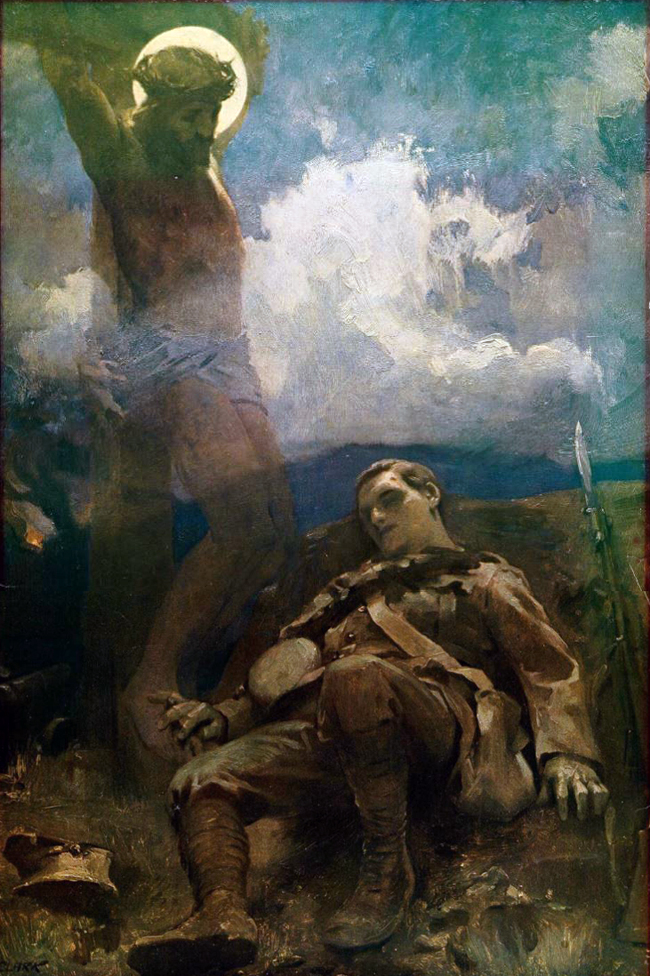

The Great Sacrifice, James Clark, 1914

Long ago I read an article having to do with prison reform which suggested the term “time horizon” to mean the degree of one’s subjective ability to connect today’s conduct to tomorrow’s outcome. Some people spend their days smoking dope on the corner with their buddies. Some spend their years studying medicine to help their neighbors. The difference is explained in part by “time horizon”: sacrifice today for a better tomorrow.

We think of Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice Isaac as paradigmatic, though it ended in a substitute sacrifice. It is a counterpoise to the standard human blood sacrifice of the pagans. An announcement that henceforth we don’t sacrifice our children. Not to the end of killing them, anyway. Instead we sacrifice them, in a manner of speaking, to build a better life.

Parents have a window of opportunity with their children, which begins to close almost from the moment of birth. You have to sacrifice your child during that window of opportunity, the earlier the better. This sounds brutal, but stay with me. You sacrifice your child to his own better future. The child you sacrifice is the selfish whiny little brat who would, without the sacrifice, grow up to be dependent, lazy, impulsive, addictive, and generally toxic. You sacrifice that child to discipline, and you sacrifice peer companionship with him. They’re not playmates or playthings or a hobby, cute as they may be. They’re a sacred charge.

When we cultivate a long time horizon, we do so as a matter of internal self-discipline, in which we sacrifice goof-off time today to get homework done for a better tomorrow. Or dessert today to have the body in better shape tomorrow, or expressions of love today when we don’t feel like it, for a better world tomorrow. We can do those sacrifices today because we see the benefits in the future, and we see if our time horizon is not inches from our face.

I should add that this is not a one-way street. What I mean is that our choice is not to just say yes or no to the proposition that we should sacrifice today for a better tomorrow. That’s not the choice. The choice is between sacrifice now and self-consumption. By failing to sacrifice we don’t leave our future statically unchanged. We leave it horribly burned up in waste and destruction. This means sin like selfishness, but also suicide, nihilism, despair, euthanasia, mass murder, sodomy, cannibalism. Very likely, hell is not merely symbolic but is a necessary antipode to heaven. It’s all one way, or all the other. There is no nice beige tepid middle ground. “Because you are lukewarm—neither hot nor cold—I am about to spit you out of my mouth.” Auschwitz was a shadow to glory, or all is Auschwitz.

The self-discipline that enables us in this way comes from somewhere, we weren’t raised by wolves and taught “that which does not kill us makes us stronger,” like Nietzsche wrote, one of the more absurd aphorisms prevalent in our absurd culture, featured in the absurd movie Conan the Barbarian featuring absurd bodybuilders. The self-discipline originates outside ourselves, ideally from family instilling it in our earliest years when it is still possible. Children don’t acquire it from the ether but we sometimes think they do, because after all they figure out how to eat and walk and talk with minimal coaching and that seems to come from somewhere. It does come from an inward drive, but the drive is not trained. It is powerful but undisciplined. We don’t pick up a gun and say “ready, shoot, aim.” We aim first, or else the gun is not merely useless, but murderously dangerous.

At Passover, the lamb was slain so that the angel of death would pass over. This should sound familiar to Christians, or anyone steeped in a post-Christian culture still charged with Judeo-Christian principles. The Hebrews sacrificed the lamb today, for their salvation tomorrow. The sacrifice of today for tomorrow is relatively easy to describe and apply for an individual; less so for a society. But the central idea of sacrifice for a better tomorrow radiates out into society at large and over history in its eons, expressed in social institutions and culture.

If this were the whole meaning of sacrifice, it would still be enough to begin to make sense of the world and to make us human beings rather than animals. But there’s much more. Consider the concept of atonement. One atones for guilt. Where does guilt come from? Why would you ever feel guilty about anything? It’s because you violate your conscience, unless you allow your conscience to become so scarified and cauterized that you lose sensitivity to violations of it and live from impulse to impulse, not caring that you’re a burden to others. Whence the conscience? I say it’s God-given. The only alternative generally on offer is that it is naturalistically evolved. So we just feel it. But if so it has no authority over us, and that means we can easily reason our way out of obeying it.

In the Abraham/Isaac story there is no particular sin for which we’re to understand Abraham must atone. Rather, guilt and the sin that produces it is endemic to mankind; it is a signal feature of human existence. It’s why the paradigm-setting stories of Genesis relate the story of the fall, and why it is reiterated countless times, as with Cain and Abel, the Tower of Babel, the betrayal of Joseph, the resentment of the freed slaves, and the sundering of boundaries in devolution of value hierarchies, told and retold all through the history of the Jews. The validity of the “sense of sin” used to be quite an obvious thing, but it no longer is, in this strange new world. We abandon the God who “hovers over the waters” of chaotic potentiality and relax into its undisciplined flow. The sense of sin, or guilt, is an anachronism, we’re told, imposed on us by religion or tradition or outdated conceptions of what it means to be a human being.

Or else it’s real because we actually do have a sin nature, and it goes all the way down to the soles of our feet and into the dust from which we were formed, and we can demonstrate our understanding of it by atoning. This means sacrifice. And maybe not just the sacrifice of one more cookie and all the cookies it represents in favor of better stewardship of the body and more energy and better ability to continue the striving for a better tomorrow. Maybe it means also sacrifice when we don’t see the benefit of the sacrifice. A sacrifice just to acknowledge God’s ultimate sovereignty. The “pleasing aroma” the prophets were always going on about.

We sacrifice to atone, but the sacrifice always redounds to our own benefit. This is the awesome beauty of the whole thing. We give and by giving we get. Your small child offers you the best he has. So sweet. How do you respond? With “good measure, pressed down, shaken together, running over.” A picture of how our meagerest offerings of gratitude return to us many-fold. Abraham was allowed to sacrifice a substitute, and not only kept his son but founded a nation. The Jews in Egypt were allowed to sacrifice a substitute, and not only kept their lives but gained their freedom. Remember the short story by O. Henry, The Gift of the Magi? A young husband and wife each give the other something they treasure, but in doing so are unable to use the gift they receive. So it’s a one-way gift, you might say; a sacrifice, but in exchange they receive something far more precious, the other’s loving motivation for the sacrificial gift.

This is why the concept of sacrifice is so confusing. We do it feeling that we’re giving up something transactionally. But everything is inverted in the whole Jewish and Christian story. God gives us something infinitely, incalculably precious. What do we sacrifice, to get it? Only the worst about ourselves. Our addictions, our adulteries, our disloyalties, our cruelties, our nihilism, our hopelessness, our disappointments, our despair. We give up our outhouse and get a palace in exchange. God is not fair.

Sacrifice is related to the “mimetic desire” René Girard wrote about. It takes some effort to begin to see the world through Girardian lens, so to speak, but it’s worth the sacrifice. Here’s the basic idea: we form our desires through imitation of others. “Mimetic desire” summarizes this phenomenon. Apart from physical needs like food and shelter, we basically want what we see others want. Let’s say you’re wearing a coat I admire. I covet it. I’d like to have your coat. But my desire for the coat doesn’t just arise from my own admiration of it. It arises from your admiration of it. I want what you want. The tenth commandment doesn’t just mean you shall not desire your neighbor’s wife or things. It means you shall not desire what your neighbor desires just because he desires it. The concept of mimetic desire seems to be built into the commandment.

We’re to break the cycle of mimetic desire, not continue to feed it. “Thou shall not covet” is foundational to how we’re to relate to one another. Can you imagine a world in which we cease forming our desires around what society tells us we should want? Maybe the planned obsolescence of fashion would dry up and blow away. Maybe we’d stop making judgments about each other on the basis of how much useless junk we own. We could for once stop sizing each other up over possessions: whether we drive a cool car; whether we have a hot wife; whether our kid got into Prestige U. And look, this goes all the way down, we all fall into this. Maybe your point of pride is driving a 20-year-old pick-up truck and shopping at Goodwill. Reverse snobbery is still snobbery.

How I finally began to grasp the significance of Girard’s mimetic desire was to understand the mediated element of our desire-formation. A point-to-point linear desire would be like thirsting for water. There’s you; there’s water, the desire is immediate. But imagine less immediate bodily desires, and instead of two points on a line, imagine a triangle. There’s you and there’s the object of your desire, but it’s not direct. Between you and the object is a third point, a mediating influence on what your desire is. That mediating influence is another person, and that person’s desire.

But it’s not just one other person, it’s society at large. We have mutual self-awareness; sometimes referred to as metacognition in regard to other people. “Intersubjectivity” is the means by which we not only are self-aware (or meta-cognizant) but we are mutually aware of others’ self-awareness, and that mutual self-awareness means a society is formed, and that society is an entity distinct from each of us. Intersubjectivity enables the mediating effect of mimetic desire through all of society.

My family moved to Germany when I was in the 10th grade. Everyone in the American school there seemed to be wearing the same thing. Straight-leg Levi’s blue jeans (when bell-bottoms were in fashion in the States), converse tennis shoes, and athletic socks with the brand name “Pro-77.” We referred to our footwear as “pro’s and cons.” I didn’t realize it right away, but this was largely because nearly everyone there was a military brat like me, so like me they got their clothes at the PX, the post exchange, which had very little selection. But that didn’t matter, what mattered was that we desire what others desire, especially in high school, a time when you would give anything to conform to whatever everyone else is doing, saying, and wearing. Even thinking, I’m embarrassed to say. Thought conformity is really important in understanding the significance of mimetic desire. I couldn’t wait to get pro’s, cons, and Levi’s.

You think of Levi’s or whatever as being the “in” thing not because your friend Ralph likes them, but because it’s what society approves. Thoughts, too, can be an “in” thing, as when we as a society approve of (indeed, insist on) anti-bigotry, but tolerate ideological exclusion.

Intersubjectivity means the desire-producing function is elevated from the desires of your immediate neighbor or neighborhood, to a larger society. Now think what that means when mass media is made technologically possible. Now we can instantly see across an entire society what strains of thought are fashionable and approved; and what strains are disfavored and explicitly disapproved. And this across an entire culture. And remember, this is especially important for young people. My Dad didn’t suddenly develop a hankering for Levi’s.

Now let’s go another step. Now we take the temperature of the culture around us by means other than just turning on the tv, or by intensely watching our high school friends to see what kind of music is cool, or by absorbing the bohemian chic the cool culture mavens present for our delectation. Now, God help us, we have social media. Our children are being sucked in by their eyeballs, ears, and brains, thence to be digested and regurgitated in a form acceptable to the collective, to an extreme unimaginable to their parents, let alone their grand or great-grandparents.

What we have is not individuality but the leveraging of automation on a massive scale. Our technologies, especially social media, are a solvent for all things worthwhile in life. People used to go to their computers (including their phones) to escape from reality. We need instead to seek refuge in reality in order to escape computers. The hyperreality of social awareness, amped beyond measure by social media, replaces directly, this-for-that, our conception of heavenly reality, even as the physical earth below our feet dissolves in favor of the back-lit screen. Nothing is real. All is hyperreal. This is an element of dystopia, a satiety of meaninglessness. You must scramble if you would preserve the inviolable, irreproducible child of God that you are.

Table of Contents

Albert Norton, Jr is a writer and attorney working in the American South. His most recent book is Dangerous God: A Defense of Transcendent Truth (2021) concerning formation of truth and values in a postmodern age; and Intuition of Significance, a 2020 work weighing the merits of theism against materialism. He is also the author of several award-winning short stories, and two novels: Another Like Me (2015) and Rough Water Baptism (2017), on themes of navigating reality in a post-Christian world.

NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link