by Guido Mina di Sospiro (June 2023)

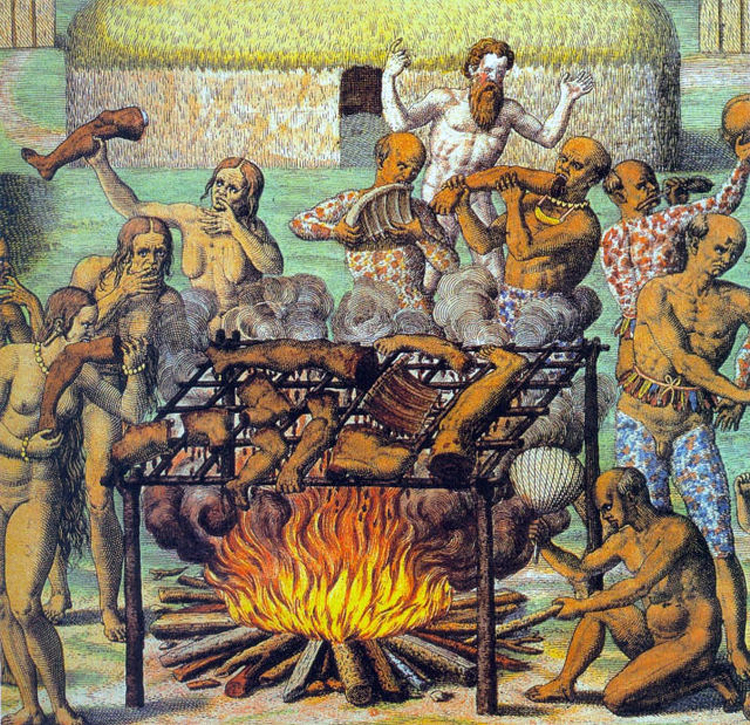

Canibais (for Volume 3 of Hans Staden’s Collected Travels in the East Indies and West Indies, depicting cannibalism in Brazil), Theodor de Bry, 1594

The “wheel of fortune” is a better analogy for history than the “evolution of humanity.”—Nicolás Gómez Dávila

In the 1980s, I used to go often to West and East Germany, essentially but not only in order to reach, by car, West Berlin. The contrast between West and East Germany was self-evident: in the former, BMW and Mercedes sedans cruised at vertiginous speeds along perfectly smooth three-lane autobahns; in the latter, smoke-belching, two-stroke, two-door Trabant mini-cars struggled along shabbily built roads reminiscent of third-world airport runways well below the low speed limit of 100 kilometers per hour (62 mph), when there was no limit in West Germany. In the German West, all cities had been rebuilt and by then expanded; in the German East, one could clearly see the scars and in some cases the wounds of WWII. And yet I had a few discussions with casual debaters in East Berlin; they were all persuaded that their Country, East Germany, was better off than their capitalist counterpart, and tried their hardest to persuade me too. In a court of law denying evidence is a crime, but for a Communist it is a desirable and time-honored policy. As the historian Robert Conquest stated in an interview: “Karl Marx said that he had discovered the science of society, how to predict the future, how everything will evolve, ‘if you do it my way.’ If it’s the only way, the scientific way, and if you reject it, you are acting against reason, you are acting against knowledge, you have to be suppressed. And then we got it, communism.” Clearly the Marxist scientific prediction could not be wrong: East Germany had to be better than West Germany. I was a young man with very little patience in general and even less for nonsense. But one night, I remember, I debated an East German young Communist almost until dawn. By then, he finally conceded: “OK, we may not be quite yet as well off as West Germany, but capitalism has had centuries to develop, whereas Communism in East Germany but a few decades. Give us time, and we’ll show the world how much better Communism is. Science can’t be wrong.”

When it comes to predictions, by pretending to be a “science” (which, as such, is supposed to make accurate predictions), Marxism cannot but be infallible. Although it has failed everywhere it was adopted and may fittingly be described as a man-made calamity, every new Marxist regime believes that this time they’ll get it right, since they have science on their side. Never mind if Cuba went from being one of the most prosperous Countries in the Americas to one of the poorest; never mind if exactly the same happened to Venezuela a few decades later. With the future being an unknown variable, every Communist regime tends to paint a rosy picture: “You’ll see: we’ll create the utopian classless society predicted by Marx in which every individual will flourish.”

And that for what concerns the future; never mind what happened to similar social experiments before; “We,” the latest Communist regime states with complete certainty, “will get it right.”

But what about the past? How does the Left deal with the past? By painting a picture that, once more, does not correspond to reality—and, it must be acknowledged, they are matchless at that.

A few examples are in order. Where to begin? Take the much maligned Spanish Conquistadors: among many other dreadful things they did to the natives, they infected them with smallpox and influenza, thus causing tens of thousands to die. How many times have we read it in history books? However, we seldom if ever have read, in the same context, about the origin of syphilis. Arriving in Europe shortly after the discovery of America, the syphilis epidemic raged across the continent, killing up to five million people—far more than the native population in all of the Americas combined. And where did syphilis originate? There follows a colorful excerpt from the book The Rivers Ran East (published in 1953 though the adventures therein date back to 1949), by the explorer Leonard Clark: “It has been established that prior to the discovery of America and the ancient Incas, syphilis was unknown in Europe. Nearby pre-Colombian Incan graves were at the moment producing—under the spades of a Lima scientist—the bones of syphilitics, due, he believed, to the Andean Indians’ working with llamas and the ancient instinct for sodomy. Very likely humanity owes this curse to Pizarro and the Andean llama. There was a national law which forbade any male Indian from traveling with a herd of llamas on a trip exceeding twenty-four hours, unless a woman went along. And since all available women were working shifts in the mines, the llama trains were stalled indefinitely.”

Another instance of rewriting of history has to do with Hernán Cortés’s conquest. In his book Los Invencibles de América, Jesús Á. Rojo Pinilla maintains that, far from committing genocide against the Aztecs (or, more correctly, the Mexica) in what is today Mexico, Cortés and his Conquistadores saved them from a self-inflicted holocaust. The Mexica had fattening pens in which children and young virgins were kept, there to be fattened and eventually eaten. If you thought the witch imagined by the Brothers Grimm in Hansel and Gretel was nasty beyond belief, the Mexica carried out that nightmare on an industrial scale. Animal husbandry (much like the concept of the wheel, or a metallurgy capable of producing steel) never occurred to the Mexica: it was more expedient to eat people. This was not limited to the occasional sacrifice to their bloodthirsty gods; it was an ongoing, all-pervading phenomenon. This slightly disturbing gastronomy characterizes the Americas: with the exception of contemporary USA and Canada, from contemporary Mexico all the way down to Chile anthropophagy was a way of life (?), or rather, of gradual self-annihilation.

The contemporary western canon, in the face of historical and archeological evidence, teaches us the opposite: that pre-Columbian Mexico was the Garden of Earthly Delights and that the Conquistadors proceeded to exterminate everyone. However, DNA testing on contemporary Mexican population reveals that 30% of them are of pure Aztec or Maya descent; 60%, mestizo; if such extermination had really occurred, wouldn’t the DNA of the contemporary Mexican population reveal that most of them are of Caucasian descent?

In the twentieth as well as in the current century we have been blessed with promulgators of great truths, such as Hollywood, which has lately annexed the field of TV series. A recent instance of rewriting history is to be found in the series The Queen’s Gambit. Based on the 1983 novel by Walter Tevis,[1] from the mid-1950s into the 1960s, we are shown the life of Beth Harmon, a self-taught American chess prodigy who rises to the top of the chess world by eventually defeating a Russian grandmaster. This is pure fiction, or retrograde wishful thinking. The naked truth is that there are no women in the top one hundred chess players in the world.[2] As for a self-taught female chess player from rural America in the 1950s and 60s defeating a Soviet grandmaster (who was trained by the best schools and players then in the world), that was/is not just unrealistic but outright impossible.

Disclosure: I am a chess aficionado and am conversant with the history of the glorious game, as well as with its main exponents, many openings, some of the more famous games, etc. Nowadays anyone from anywhere in the world, provided (s)he has a reliable internet connection and time at disposal, can learn the basics all the way to the most sophisticated nuances of the game; view historical matches, with move-by-move comments; learn openings; try to solve quizzes; get one-on-one tutorials from accredited masters; participate in tournaments—all thanks to chess.com. Despite all that, there continues to be a lack of world-class female chess players. With chess being widely perceived as the ultimate intellectual activity, overwhelming male dominance is routinely cited as an example of manifest male intellectual superiority.

So, what does pop progressive culture decide to do to fix that? First of all, presumably without realizing it, it decides to accept tacitly the two postulates: A) chess is the ultimate intellectual activity (which is, in fact, highly debatable), and B) overwhelming male dominance in chess is a clear indication of male intellectual superiority (also highly debatable). Granted, the IQ of these purveyors of progressive pop culture is in all likelihood in double digits (alarmingly [or not surprisingly?] that of half of the population), but still, I would be hard-pressed in coming up with a more staggeringly imbecilic answer to women’s inferiority in chess than reprising a fabrication in which a self-taught orphaned girl from rural America in the 1950s with drug abuse problems manages to defeat the best grandmasters from the Soviet Union. It is too sublimely stupid to be true: the makers of The Queen’s Gambit acknowledge and accept that chess is the brainiest pursuit and that women suck at it; the answer, they figure out with a stroke of genius, is to exhume a novel of the early 1980s from oblivion and pretend that, instead, one woman rose to the very top of the chess world, and seventy years ago. If they were possessed of high culture and an IQ in triple digits, they might have realized the following:

A consummate chess player is both a homo ludens and a homo belligerans. Homo ludens means playing man, or, a man who plays. Dutch philosopher of life Johan Huizinga wrote an inspired book just by that title. In it, it becomes apparent that man, far more than woman, yearns to play, at all times of his life. Women have many other pastimes; men are hell-bent on playing, just about any game—and not for money: playing for the sake of playing is the point; it is a yearning as instinctual as libido. As for homo belligerans, i.e., warring man, Italian philosopher Filippo Valenza wrote: “Homo belligerans is the eternal man. The warrior suspends the (homo) faber (maker) and the (homo) sapiens (knowing) to remain only belligerans, a hard yet elastic and ductile instrument of war. He suspends man in himself, shuts him up momentarily in a parenthesis to assert his right to be man.” Recorded history eloquently testifies to both realities: immensely more than woman, man is attracted by war, and just about any pretext is good enough to start one; the same applies to playing games. And since chess is both things at once, and that is, a game that emulates war, how keen on it can a woman really be compared to a man? Is a woman going to spend her whole life obsessing over how to weaken the Sicilian Defense?[3] Some male chess players have done just that …

Another exquisite exercise in rewriting history, and/or in describing an utterly implausible reality, is to be found in action movies and TV series, featuring female leads. Ana de Armas in Ghosted; Jennifer Lawrence in Red Sparrow; Charlize Theron in Atomic Blonde—a few examples of a great number of movies in which secret agents, usually gorgeous and petite women, manage to wrestle with trained male assassins one or two heads taller than they are and, say, a hundred pounds heavier, and invariably win. They are female James Bonds, except a lot better, faster, more athletic and cunning. If we were asked to believe that female secret agents outsmart men, I would have no problem with that; but asking us to believe that a 5 feet 5 inches tall woman of 115 pounds can fight and defeat a 6 feet 4 inches tall male trained assassin of 230 pounds, mostly muscles, is asking for a major dose of suspension of disbelief. The only way I could enjoy such movies would be by considering them camp, at which point, anything goes.

Conversely, the Colombian TV series Undercover Law (La ley secreta) tells the stories, based on real-life facts, of four women who are undercover agents of a special police force headquartered in Bogotá. Their roles are far from glamorous: one is water-boarded almost to death by her objective, with whom she has nevertheless fallen in love (a major faux pas), thus, incidentally, ending her own marriage; another one is forced to join the guerrillas in the jungle, risks her life many a time, is wounded, raped and impregnated by the leader of the guerrillas, a most appalling brute if there ever was one, and yet she carries on, as all her colleagues do, for “God and Country” (Dios y Patria); another one, after innumerable tribulations, loses her husband by the hands of the cartel they both had managed to infiltrate; and the fourth one is abducted and shot at, both many times, and nearly killed, while her niece, to whom she acts as a mother since her sister is a heroin-addict, is also kidnapped—the reality is millions of miles away from the farcical Hollywood female secret agents invariably succeeding in their herculean tasks. But the Colombian secret agents, enduring all that, truly come off as unsung heroines, which they are. The viewer is moved by their vicissitudes and their indomitable resolve in the face of all abominations and dangers. On the other hand, the rank nonsense that Hollywood inflicts on us can only result in involuntary comedy.

There are countless other examples of this curious yearning for rewriting history, whether past or future; finding verisimilitude in what we read, see or hear from whatever source has become increasingly difficult, but I trust that readers of NER know just how to keep away from inauthenticity.

[1] Back in the Reagan Era, eleven years after the 1972 World Chess Championship in which Bobby Fischer of the US challenged Boris Spassky of the Soviet Union in the “Match of the Century,” and ended up winning, a novel in which a US female player of humble origins, indeed an orphan, defeats a Soviet grandmaster was a further slight to the Soviet Union or, as Regan called it, the “Evil Empire.” That specific rewriting of history may well be interpreted as a provocation against Communist Russia. The rewriting of history of a TV series of thirty-seven years later has an entirely different meaning.

[2] A very, very few outstanding female chess players, above all the Hungarian Judit Polgár, have left their mark in world chess, but they have been the exception, not the norm.

[3] For example, the Rossolimo Variation by Nicolas Rossolimo, and the main reason why he is remembered.

Table of Contents

Guido Mina di Sospiro was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, into an ancient Italian family. He was raised in Milan, Italy and was educated at the University of Pavia as well as the USC School of Cinema-Television, now known as USC School of Cinematic Arts. He has been living in the United States since the 1980s, currently near Washington, D.C. He is the author of several books including, The Story of Yew, The Forbidden Book, The Metaphysics of Ping Pong, and Forbidden Fruits.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

3 Responses

There are so many other examples of the mutilation of history that di Sospiro should have cited.

This was not supposed to be an anthology: an impressionistic presentation renders the picture. But yes, when choosing examples I was confronted by an embarrassment of riches: dozens and dozens came to mind. In the end I opted for Marxism, the greatest prevaricator; anthropophagy in the Americas on a very vast scale, and how it has been officially concealed and denied; and the war of the sexes, and the way Hollywood turned it into a camp spectacle.

Very good, and very interesting. I had no idea llamas were so implicated. 🙂