by Geoffrey Clarfield (November 2022)

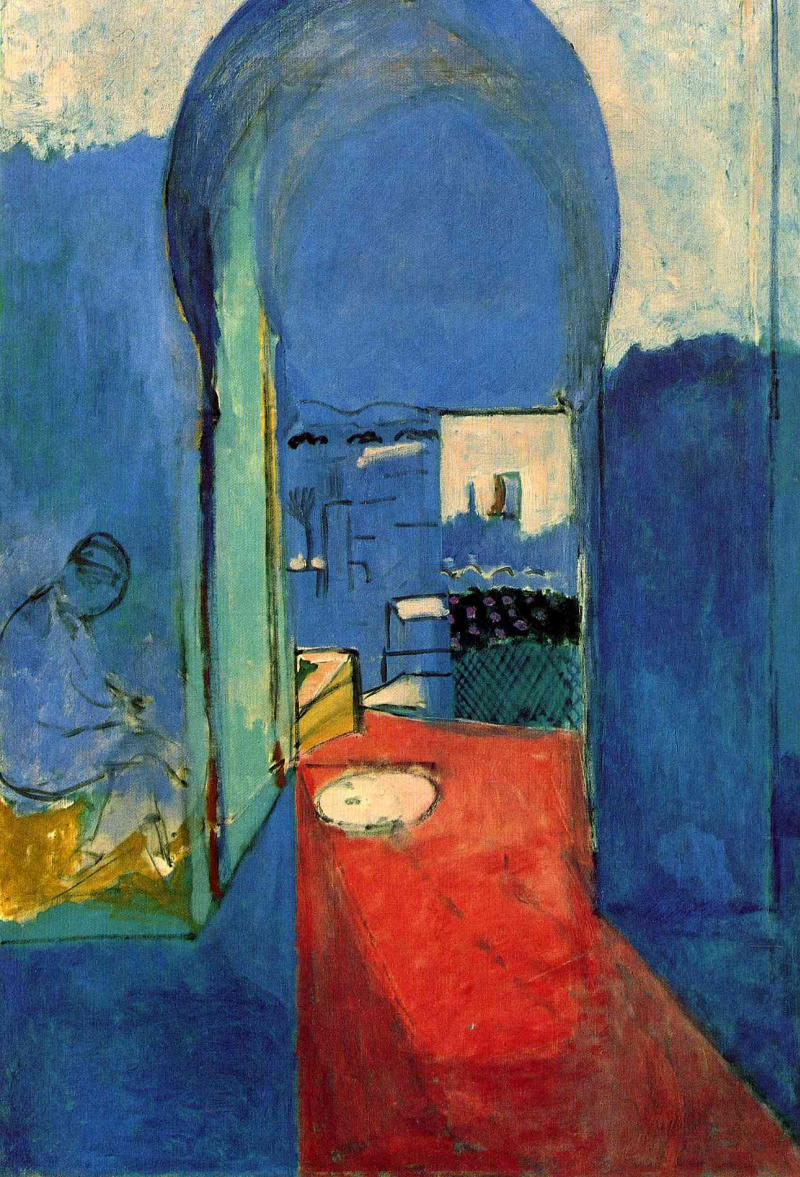

Entrance to the Kasbah, Henri Matisse, 1912

I am an early bird. Up before the sun. I go to the kitchen and boil water. I take out my Israeli coffee from my glass jar that I bought in the nearby market. I add sweetener and then I add milk which is delivered to me daily from a nearby farm by Hamza, my milk man.

I mix it all together and wait for the coffee grains to subside. I just “know” when it is ready. I got the taste for this kind of coffee one summer as a teenage volunteer on a kibbutz in the Valley of the Jezreel.

They call the concoction “botz,” which means dirt in Hebrew, and which is as a good an expression of the egalitarian ideals that were still popular when I grew up in an Israel that was slowly disengaging from decades of a strange residue of what was once called Marxist Zionism.

In those days it would have been unseemly to have called it “Luxury Turkish coffee” but that is more or less what it is, at least my boutique variety. And so, every morning I start my day in my house in Tangier with this coffee and my bittersweet memories of agricultural labor as a summer volunteer.

As I love all Moroccan music, I begin my day drinking my coffee and listening to the cacophony of early morning prayers broadcast (and with the smaller mosques sung) from the minarets near the old city where I live. It is wonderful and melismatic. I love it.

I imagine my more religious Moroccan Muslim colleagues and employees conducting their first of five daily prayers called Salat in Arabic and consisting of eight ritual sequences which can be done within twenty minutes: taqbir-raising of the hands and proclaiming God is Great, Qiyam, crossing the right hand over the left, Ruku-bowing towards Mecca, a second Qiyam and then Sujud when the worshippers all kneel, Tashahud -kneeling position, repeat of Sujud and Tashahudd. All the while the worshipper focuses on the collective outward forms of his religion in between moments of quiet self-reflection.

I have watched these prayers from a balcony above the grand mosque of Tangier and always marvel how this Jewish invention of belief in the one God, was transformed in Arabia in the 7th century AD, from where it then spread to the rest of the world including this once Phoenician and then Roman city of Africa, Tangier which is now my home. Not all Muslims pray five times a day, but all Moroccan Muslims know how to pray and at this level their monotheism is unquestioned.

Indeed, the great Rabbi, doctor, politician, philosopher and head of the Cairo Jewish community of the Middle Ages, Maimonedes (Moshe Ben Maimon), a man born in Muslim Cordova and who lived in Morocco on his way east, once wrote to his fellow Jews during the Middle Ages that Muslims are not pagans as they also believe in one God. Whereas with Catholic Europe … well for those interested I suggest they consult a university library.

Soraya is a cousin of my housekeeper Zainab, who had gone to visit her relatives in the mountains of the Rif for two weeks after the birth of a fourth girl to one of her cousins. They needed some help at home.

Soraya was young and unmarried. She was about twenty when we first met. She has high cheekbones, brown hair, brown eyes, a silver tooth and she wears traditional Moroccan clothes with a bit of a French designer’s panache. When she goes out in her female style djellaba (Moroccan cloak) she always carries a Luis Vuitton knock off purse that must have been made in China.

She can read and write but had to leave school after grade eight. Morocco is filled what I call these “half completed” men and women, who are literate but who never made it through high school or college. They can read and write but still look at the world through folkloric eyes.

They believe in Jnun (genies), baraka, the power of saints to cure and protect them along with black magic, sorcery and spirit possession. They are a new anthropological category and make no sense to the liberal and left leaning anthropologists who talk about “levels of modernization.” Soraya is one of them with a foot in the modern world and another in the land of sprites and fairies.

She quickly got to work making my breakfast, the Moroccan scrambled eggs called Shakshouka so beloved of my grandmother’s kitchen (She was born in Tangier before WWII). I was not busy that morning and had only to go to the office after lunch and a Consular cocktail party in the evening, which was a kind of cultural memorial to a recently deceased Israeli pop star named Zvika Pik.

He is not known in the West but was big in Israel. His daughter married the American film maker Quentin Tarantino. They live high profile lives in Tel Aviv, but I am told his wife keeps a Kosher household. Tarantino has offered his services as MC for a concert of Moroccan Jewish musicians that we plan for the coming summer tourist season here in Tangier.

I turned on the radio and was listening intently to the latest in Moroccan pop music which uses so many studio effects and electronic instruments that the rawness and creativity of this musical tradition can barely be heard amidst the noise of all the synthesizers. And then there will be a blessed half hour of musical relief, Hussein Slaoui, Sami El Maghribi, and El Hamdawiya who were all acoustic back in the day and then once again, I feel I am really living in Morocco.

After breakfast I sat and had tea with Soraya while she munched on a half loaf of Berber bread that had been delivered fresh from the local baker a half an hour earlier. She dipped the bread in the tea and said,

“Oh, Sidi (sir) … I have no money, my parents are illiterate, I fear my brother smuggles hashish from the Rif into Spain. I fear for his life, and I have been going to the shrine of Sidi Hosni el Wazzani here in Tangier in the hope that he will help me get money. It is not that I do not like working for you and other expatriates, but without money, no dowry, without dowry, no good marriage, without no good marriage, no children, without children, no baraka (blessing) without children who say prayers on your tomb after you die, without children …”

I stopped her just before she complained that without children, she may never enter paradise and summarized her predicament, “You need to find a way to make money, is that it?

“Le Hamdi Lilah! God be praised! Andaq el Haqq—you are right!” she said as if she had just thought of it.

I told her I would think about it and get back to her and then I had to leave. When I got to the office, I found that most of the staff had taken their holidays together and were lounging on the beach somewhere. And so, I spent the day pushing paper and writing other people’s reports.

In the late afternoon I went for a walk on the beach. The storks were out in great numbers. I could smell the fish in the salty sea water, and I watched from a polite distance as a group of turbaned and djellaba wearing Tangier fisherman brought in their catch of the day.

I struck up a conversation with the eldest and told him about the plight of people like Soraya. He said, “Yes, we have many children, the cost-of-living rises, we cannot afford further education for them, so we are going quickly from a third world country to a second world country. There is no honour in this.”

That evening I was invited to a gallery opening sponsored by the Alliance Francais. All the regulars of the Consular community were there, alone or with partners. The hip new Moroccan cultural elite of the city were also there. There was wine and bitings done in that fabulous Parisienne manner and the mixture of French, English and Moroccan Arabic spoken was enough to create a new creole for the city of Tangier.

The next day Soraya came to help in the house and after breakfast she told me that she had had a luminous dream in which she had visited the tomb of Sidi Hosni al Wazaani. She had dreamed about Solomon’s Ring, and that it had given her an invisible magical power which she understood would bring money from Jews and Christians, but not Muslims. She was perplexed and asked me if I knew what the dream might mean.

I had read about this ring in Westermarck’s remarkable compendium of Moroccan folklore which I believe is now over a century old. I thought this belief had died out decades ago, but apparently not. I pulled out the book from a shelf and slowly translated the following section into simple Moroccan Arabic,

Thus, Siyidna Suleiman had a wonderful ring … by means of which he ruled over the jnuun, as well as over all animals and birds in the world and the winds; it had been given him by Allah himself. Once however he lost this ring. A certain Afrita sent her servant an afrit, to watch for an opportunity to deprive him of it, and throw it into the sea and so the afrit did one day when Siyidna Suleiman had gone to the hot bath and their removed the ring from his finger…

The story went on with many twists and turns and ultimately, the king got his ring back. Soraya asked me once what the dream might mean, and I could not answer her until the following day.

After breakfast I said to her, “Once upon a time in Europe not too long ago, there were two doctors…” (She thought that I meant scholars of Islam, but that is not important.) “One was named Sigmund and the other was named Carl. Carl studied with Sigmund, and they asked people about their dreams so they could feel better about themselves. They eventually agreed that dreams are a combination of your fears and hopes and that they differ for different people.”

This was news to her, and she said she would visit the tomb again today.

The following day she told me that she had dreamed that she was the tea maker for King Solomon and that every day before he gave judgement, he read from a book with beautiful pictures. She would look at them from behind his shoulder for she explained that although the King had long legs, his body was very short. Where did she pick that one up from? I asked her if she thought she could draw these pictures. She said she would try.

Over the next few weeks, I gave Soraya the afternoons off to draw in my courtyard. She was a natural but a primitive, and drew portraits and characters from the Koran, especially the stories that are Biblically inspired like Joseph in Egypt. She produced thirty drawings, all charcoal on paper. She asked me to take them to show my expatriate friends. Perhaps they would pay her for them, just a few dirhams she added, “Inshallah” that is to say God Willing.

I took Soraya’s creations over to the Alliance Francaise which has a concert hall and an art gallery. My friend there Francois, who is their advisor for visual art and photography (what else can you do with a BA in fine arts from the Sorbonne?) and he liked them very much.

Two months later we had an exhibit of Soraya’s work, jointly sponsored by the Hebrew Language Institute (the King had spoken at our opening some time ago) the Israeli Consulate and the Alliance Francaise. I and Francois had coached Soraya on how to deal with the public and the press.

The press gobbled up her work and story and praised it to the skies. She also charmed the guests and drank no wine. She sold every one of the thirty paintings and within a week had accumulated more than enough money for a dowry that would land her a middle-class husband, at least someone with a high school diploma and prospects of making money. I had expected her to assertively grasp that bitch of a brass ring that we call success, and ring every dirham out of it, but no. So, no career for Soraya.

A British writer who lived here in the 1950s had this to say about Morocco and Moroccans and it explained to me at least why Soraya had as we say, “no ambition.” In her mind everything was contingent and in the hands of the almighty.

Inshallah is very important. I have known that for a long time. But having uttered the formula Inshallah -if God wills-it is the next step that troubles the Western mind…What actually happens?…The past is the past; the present is living evidence of God’s wishes but the future is in His hands. How can you fortell what He has in mind for you when you are making your plans. Anyone can see that the very fact of failure to carry out such plans shows that he never intended that you should.

Of course, I was invited to the wedding. I am now one of the few males allowed to visit Soraya and her children in her husband’s house while he is away at work. He trusts me completely and has thanked me many times, for Soraya has given him children and a happiness beyond words.

A long, long time later, one day, early in the morning there was a knock on my door. It was Soraya. I was making my coffee and invited her in. She told me the latest news about her husband and her three children all of whom were well and healthy. She told me that she did not have any reason to continue drawing.

She wanted to give me something as she explained that when she had gone to pray at the tomb of Sidi Wazzani’s she had found a ring there in the dirt that she had worn when drawing. When not drawing, she kept it on a string around her neck.

She told me, “I think this ring gave me the Baraka (blessing) to make those drawings and I do not need it anymore. I want to give it you in gratitude, for you are the cause of my happiness. She handed me a ring wrapped in a piece of newspaper.

When I took it out, I recognized it immediately. It was a 10th century Phoenician gold ring from Lebanon with an image of a serpent on its face. The Phoenicians had settled Tangier before the Romans, they merged with the local population, and it is thought that much Moroccan folk religion has Phoenician or Punic roots. It could have been the kind of gift that King Solomon gave King Hiram of Tyre, the Phoenician king who helped build the Temple in Jerusalem.

The folk religion of Morocco is based on a whole series of pre-Islamic pagan beliefs and rites, some indigenous to the Berbers, some were brought by the Arabs and much of it may be a residue of the Baal worship of the Phoenicians and Canaanites where every hill had its own version of Baal and his consort Ishtar. There may also be a pre Islamic Jewish stream to Moroccan Berber folklore that survives in many archaic customs and rituals.

The fact that the ring ended up in the Islamicized tomb of a saint who bestows blessings and fertility is one of the most lasting and enduring memes of middle eastern culture. Who knows how it got there, but its location is not accidental. It carries blessing, Baraka, power.

I asked Soraya how she came upon it.

She said, “The day after I visited the Saint’s tomb, I prayed that I would find Solomon’s Ring. And as God is my witness, I found this ring buried at the entrance to his shrine. I picked it up and I have told you about the dream. This is King Solomon’s Ring, I am sure, and I want you to have it. You do not have children yet and if your future wife has difficulty conceiving, then she should pray while she wears it. And perhaps one day if you face danger you will need to call on its power.”

As I walked through the old city of Tangier and admired the marvelous mosques of this Mediterranean town I recalled a verse from the Bible.

At Gibeon God appeared to Solomon during the night in a dream, and God said, “Ask for whatever you want me to give you.”Solomon answered, “You have shown great kindness to your servant, my father David, because he was faithful to you and righteous and upright in heart.”

Moroccans believe that the Ring of Solomon gives its owner extraordinary power for good or evil. I am now the bearer of the ring. I have no idea what I may do with it. Can I be righteous and upright in heart?

Geoffrey Clarfield is an anthropologist at large. For twenty years he lived in, worked among and explored the cultures and societies of Africa, the Middle East and Asia. As a development anthropologist he has worked for the following clients: the UN, the Rockefeller Foundation, the Norwegian, Canadian, Italian, Swiss and Kenyan governments as well international NGOs. His essays largely focus on the translation of cultures.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link