Wisdom of the Ancients

by Peter Dreyer (September 2023)

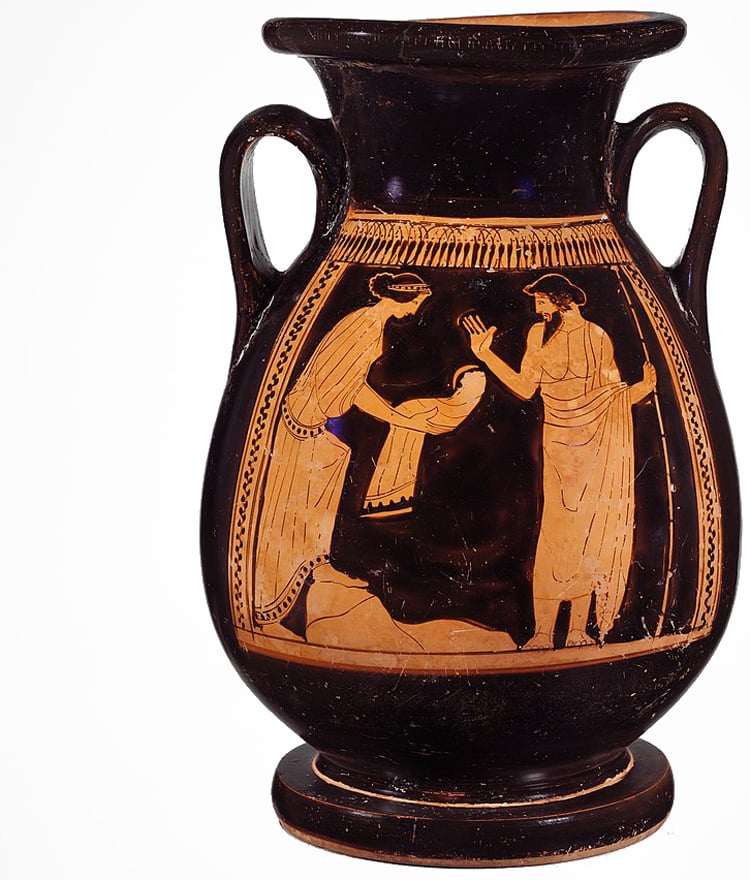

As a substitute for the newborn Zeus, Rhea offers Kronos the Omphalos stone wrapped in a cloth, Attic red figure pelikē attributed to the Nausicaa Painter, 460–450 BCE.

The boy stood on the burning deck,

his back was to the mast.

He would not move an inch, he said,

till Oscar Wilde had passed.

But Oscar Wilde, that wily bird,

he rolled the boy a plum,

and as he stooped to pick it up

[ta-tum, ta-tum, ta-tum … ] —Anon., after Felicia Hemans

Inscribed by an unknown hand on a wall in the lavatory of a Shaftesbury Avenue pub, where I found them, these lines are surely the finest parody of Hemans’s much-parodied poem “Casabianca” (1826), and they offer striking metaphors: the deck = the world; the boy = us; “Oscar Wilde” = civilization/culture; the plum = art, music, poetry …

Felicia Hemans (1793–1835) captured an important image, however. The “deck,” which is almost everywhere bursting into flames today, it seems, was already shedding sparks in the Napoleonic era, and it had been flickering since antiquity, when forests in Greece, Anatolia, North Africa, and the Levant were hacked down to build the warships in which men sailed to far-off places (like Troy) to murder, rape, and enslave their fellow human beings. A Greek city-state, Corinth, invented the trireme—called “the guided missile of the day”—as early as the seventh century BCE (Thucydides 1.12.4–13.2), and much bigger warships—quadriremes and quinqueremes—came into use in the Hellenistic era. The Romans copied these, using a shipwrecked Carthaginian polyreme as a model.

Although regarded throughout the long history of Hemans’s poem as the epitome of British courage, the original boy on the burning deck was actually the son of the captain of the French republican warship L’Orient, blown up in the 1798 Battle of the Nile by Horatio Nelson’s British Royal Navy. It took thousands of trees to make such a ship—around 6,000 reportedly went into building Nelson’s flagship, HMS Victory. England’s oak forests had been exhausted, and timber suitable for to building battleships had to be obtained from the Baltic and North America. Decks were burning all over the world.

In the early 1600s, around the time Queen Elizabeth I died, Francis Bacon (1561–1626), a lawyer struggling for political patronage in the dog-eat-dog world of Tudor/Jacobean privilege, produced a work he titled De sapientia veterum, explicating thirty-one Greco-Roman myths. Translated into English by Arthur Gorges, it was published in 1609 as The Wisdom of the Ancients.

“Upon deliberate consideration. my judgment is, that a concealed instruction and allegory was originally intended in many of the ancient fables,” Bacon writes—if not, he objects, they are simply ridiculous! The myths are poetry, however, and Bacon admits: “I profess not to be a poet.” The opposite of a poet, Yeats supposes, is an opinionated man, and Solicitor General, Attorney General, and, finally, Lord Chancellor of England Francis Bacon, Lord Verulam, Viscount St. Albans, may have been one of the most opinionated men in English history. His opinions are evidently still cited in London’s Inns of Court. A contemporary, Dr. William Harvey (who discovered that blood circulates), put it bluntly, saying: “He writes philosophy like a Lord Chancellor.”

Composed by unknown poets millennia ago to lampoon the injustices and absurdities of a world in which sickness, death, war, and slavery were ever-present realities, these fables were meant not only to entertain but, by satirizing them, to help people confront and endure horrors they could not avoid. Kafka would have understood. Bacon just didn’t get it, however, and his interpretations are what one might expect from a rising lawyer (king’s counsel in 1604, solicitor general in 1607). Quite possibly, Bacon didn’t even write the explanations himself. He is known to have employed others to work up his ideas, Thomas Hobbes, the future author of Leviathan (1651), among them—and perhaps men like Ben Jonson, Kit Marlowe, and Shakespeare.

The myths come down to us from antiquity in multiple, contradictory versions. I have condensed them into anachronizing sonnets, borrowing only a few words here and there from the Bacon/Gorges text (in quotes if I’ve remembered). To make a round number of myths, I’ve added one of my own, “Bacon, or, A Legend,” no. 32. Since they were never the creations of a single author, they should not “be read first as a sequence, one voice running through many personalities,” as Lowell asks for his Imitations, but rather as a plurality. Each stands or falls on its own, and they can be browsed. Some, I confess, are still a bit too Baconian for my liking (e.g., no. 16, “Zeus Suitor, or, A Cuckoo”), but what you gonna do!

“Cassandra, or, Prediction” is first in Bacon’s sequence—presumably because it was Cicero’s epigram on Cato the Younger, which he quotes in it, that prompted him to write the book in the first place. That position is counterintuitive, however, and I have put my version, “Cato and Cassandra, or, Talking Heads,” in twelfth place (in part 2). “Ouranos [Bacon uses the Latin “Cœlum”], or, Beginnings” more logically comes first.

As epigraphs to parts 2, 3, and 4, I use “risqué” limericks by the British poet Christopher Logue, CBE (1926–2011),[1] which (like the Shaftesbury Avenue parody of Hemans’s “Casabianca”) seem to me latter-day equivalents, in their way, of the screwball, hellzapoppin fantasies of our ancestral Indo-European bards. Logue’s unfinished epic War Music, composed for a BBC Radio program, modernizes and anachronizes parts of Homer’s Iliad, and although our approaches differ substantially, his foreshadows my own in places, viz.: ”Achilles speaks as if I found you on a vase. / So leave his stone-age values to the sky,” Logue’s Agamemnon admonishes the Greek warriors on the beach at Troy, where they have been summoned for a pep talk by “Ajax / Grim underneath his tan as Rommel after ‘Alamein.”[2]

Part I

1. Ouranos, or, Beginnings

That dome of brass Sky, Heaven, Ouranos,

and girly Gaia, Earth, a goddess of grass,

having at it in their enormous bed,

parented a brood of sons, the Titans.

She being—she still is!—a world-class MILF,

their youngest, Kronos (aka Time), gelded

Sky with Leo’s sickle of stars, the pup!

Screwing Mother Earth himself henceforth, Time

swallowed the kids that happened to show up,

and absent Leo’s adamantine tool,

mislaid in the mulch pile or potting shed,

Auntie Rhea rescued Zeus when he was born,

by fooling Kronos with a diapered rock.

Forever over, such was the strange start of things!

2. Pan, or, Nature

A shaggy, goat-footed flautist with horns

that reached up to heaven, human above,

half-beast below, Hubris was his mother

and the Destinies his sisters. Beaten

by Cupid at wrestling, he met his end,

a scholiast reports, in the reign

of Tiberius, when a voice from the shore

troubled passing mariners saying so.

His wife was Echo, and their only child,

Iambē, or Banter, famous teller of tales,

was the paramour of Pentameter,

duke of Ellington, who promulgated

the first rule for poets on Parnassus,

“It don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing!”

3. Typhonia, or, Rebellion

Zeus birthed Pallas Athena from his brain,

and Mom, captivated by her armored

mien, seeking similarly to concoct

offspring without a tarse’s intervention,

got pregnant with the help of mudlark Gaia,

a python’s egg, and Time’s chronic semen,

bunning the oven with me, Typhonia,

a rebel girl, just born to game the game.

Ripping the cables from His hands and feet,

I stashed them in my Hermès Welkin bag

(the rule of the Cognoscenti’s so neat!!),

but that mean wing-footed boy stole them back

and shitty Zeus dumped Mount Ætna on my head.

I’m down there yet—still cool, but good as dead!

4. The Cyclops, or, Ministers of Terror

Deafened by that hammering, blinded by

their conflagrations’ smoke, Zeus first consigned

the wheel-eyed wall builders to Tartarus,

or Hell. Then musing that they might as well

be put to understrap Health Care’s pious

work or contrive new thunderbolt matériel,

he had them slay for quackery some quack.

Even Mousie Apollo took a crack!

You may suppose them miscreant ministers,

bad in their nature, whetted by disgrace

and diligence done in official spite

at “private nods” and orders of the boss.

Condemned at last to confront retaliation’s

rage, they’ll meet their deserts one nasty night.

5. Narcissus, or, Self-Love

This stuck-up parvenu, contemptuous

of his fellows, comes with an adjective,

“narcissistic.” And with groupies—Echo

being the most faithful. Glimpsing himself

in a mirror, he fell madly in love,

so wild about his emergent icon

that just being there was a sensation

consecrated to self-admiration.

Loose cannon on any deck, Narcissus

rejects the huddled masses’ right to roam

to the beamish banks of “Here.” He’s Tory!

That was to be expected, no?

But the Supremish Court of Erewhon

(“Home of the Okay”) may deny certiorari.

6. The River Styx, or, Promises, Promises

The gods witness their oaths by the River Styx,

which meanders round the demon court of Dis.

For this form alone, none other but this,

is regarded as obligatory

and inviolable—cheaters are booted

from the pantheon of Olympus—

those risk the joys of Helicon’s table

who don’t swear as honestly as able.

Necessity, whose stand-in is the Styx,

a lethal stream that cannot be crossed back,

is bell, book, and candle to the mighty,

so moguls’ pledges are best ratified

by Stygian oaths engaged in on its banks,

whose breeching even bullshit artists can’t abide.

7. Perseus, or, War

Perseus was commanded by Athena

to behead the Gorgon Medusa, who

petrified the West, turning to stone all

who gazed on her. Her half-sisters the Greæ

sold her out, lending him their single tooth

and eye. Thus armed, he aimed at her image

in a mirror, severed her neck, and got

sharp-winged Pegasus from the gushing blood.

A hatchet man must demand from treason

an eye for information, and a tooth

to rumor, bite, and nibble at the truth.

Pegasus is fame, perish the reason!

Medusa’s head is history’s sigil,

the colophon to the stuff the victors scribble.

8. Endymion, or, Those Special Someones

“Pride in their port, defiance in their eye,

I see the lords of humankind pass by.” —Oliver Goldsmith

Enamored of the shepherd Endymion,

the goddess Luna got it on with him

secretly (as always wise!), descending

to nigh[3] her nitwit sweetie in his sleep,

in a cozy condominium—complete

with swimming pool—in Erewhon. Woozy

and his woolly quadrupeds multiplying,

the herding gang all were green with envy!

The stellar few depend on hoi polloi,

who greatly enjoy them in REM slumber.

A yokel’s fondest dream’s to be the buoy

of some superstar that’s got their number.

Glad to be had—if not, in fact, eager,

your land is their land, according to Pete Seeger.

Part II

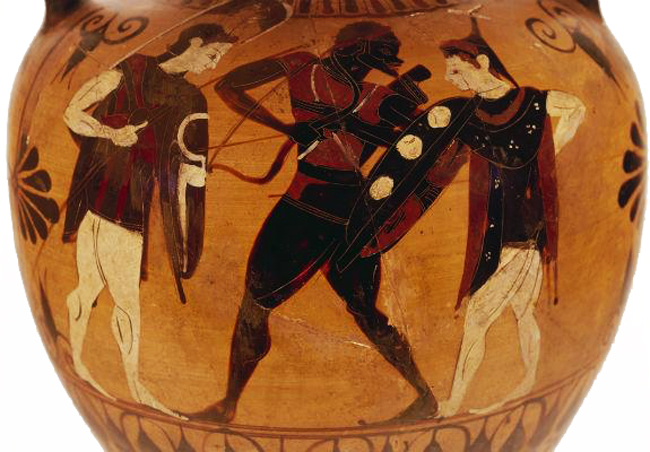

The Departure of Memnon for Troy, Black-figure vase, 550-525 BCE.

An avant-garde bard named McNamiter

Had a tool of enormous diameter;

But it wasn’t the size bought tears to her eyes.

’Twas the rhythm–dactylic hexameter![4] —Christopher Logue (Count Palmiro Vicarion, pseud.)

9. The Giants’ Little Sister, or, Fame

The Giants, seeded in Gaia by the garum

spilled when Kronos gelded his father Sky

(whose groans outraged the ocean, lust springing

from the foam), assailed the immortal gods

with red-hot trash bins and flaming barbells,

but were repelled with thunderbolts and slain.

To commemorate the death of these bums,

Earth fêted their fetid little sister, Fame.

Fame’s offspring, an insolvent lot, increase,

rebellious, wanting change, now only checked

by flashing lights and noise, their sole recourse

inventing seditious lies and slanders,

branded “fake news,” to libel, cheat, and rob

those called upon to civilize the mob.

10. Actaeon and Pentheus, or, Voyeurs

Actaeon, it’s said, saw Diana bare,

and she made a stag of him, whereupon

his own gang of hounds ripped him to bites.

Pentheus peeped at Bacchus’s sacred rites

from a treetop, whence the maddened women

dragged him down. Thinking him an animal,

they tore him bodily apart. His head

impaled, his mother paraded it home.

Did Actaeon profane Diana by chance?

Not true, they’d gone hunting together, pals—

he’d just hoped to know her better! Pentheus?

The tale’s been bowdlerized .The facts are wrong.

He’d importuned an ungendered party,

it seems, and “they” ripped off the poor chap’s …

11. Orpheus, or, Enlightenment

Delightful music calms the brutish breast,

it soften rocks and unbends the knotted

oak (not what Congreve mandates, you find

—but close). Orpheus pursues his bride to Hell

and wins her back with singing, but then quits,

loses her again, and sorry raves

to trees and rocks, annoying humankind,

who want him deconstructed, chopped to bits.

But what if Bacchus and those stonèd scolders

were the lusts and appetites, Orpheus.

Philosophy, his Eurydice maybe

its Stuff? Turned off by such detumescent

metaphors, that mob of maddened maenads,

like politicians and sausage makers, chose scraps.

12. Cato and Cassandra, or Talking Heads

Foretelling the Roman Republic’s

ruin, Cato Minor tempted cruel Fate

“as though he lived in Plato’s Republic

and not Romulus’s shit.”[5] Cassandra, too,

addressed the future. Some say serpents’ tongues

licked a sense of Troy’s fall into her ears.

Others, that it was a bribe, Apollo’s

randy tit for tat, on which he reneged

when she shrank from “doing” a god: predict

though she might, she’d no longer be believed!

Locrian Ajax had her when Troy collapsed,

his snickersnee whipping Apollo’s lyre—

for a bare bodkin may its quietus make

more ways than one—and doomscrolling’s no fun!

13. Proteus, or, Matter

Poseidon’s herdsman, Proteus knows secrets

of all kinds, but to learn them you must bind

him. Fettered, and seeking to free himself,

he shapeshifts to innumerable

forms and happenings. (Another Proteus

was a king in Egypt, and Helen’s host

when Paris took her phantom twin to Troy,

Hesiod says, but that’s different “matter.”)

Poseidon’s weapon’s the trident, symbol

of the big shebang—for he’s none other

than that sweetie Satan, cast out by Zeus

into the daily world that light reveals.

At noon, old Proteus counts his sea-calf herd;

then sleeps. So, then . . . Shut up and calculate!

14. Memnon, or, Presumption

Memnon, king of Ethiopia, Tithonus

and Aurora’s son, came from Africa

to aid Troy, his father’s city. Thirsting

for glory—only the best good enough

for him!— he fought Achilles one-on-one,

and thus, need it be said, died. Zeus sent birds

to grace his obsequies, and morning’s light

from his statue evokes a mournful hum.

Pausanias, who heard it, attests the noise

but in his day the statue was broken

in half—the myth says by the King of Kings,

Thingamajig. This sorry story tells

us little, beyond the usual end

of glory. Fame’s such a pathetic gig!

15. Tithonus, or, Too Much!

The immortal gods despised old age, but

Tennyson gives to Tithonus these lines:

The woods decay, the woods decay and fall,

The vapours weep their burthen to the ground,

Man comes and tills the field and lies beneath,

And after many a summer dies the swan.

As imitator, I clearly plead fair use—

no one could ever hope to say better!

Tithonus, seeking immortality,

forgets he will grow old, while his bride, Dawn,

remains forever young. “And all I was,

in ashes. Can thy love, / . . . make amends . . . ?” Yes!

Dawn does not reject him, Propertius says.[6]

Well, dear reader, how does that sound? Okay?

16. Zeus Suitor, or, A Cuckoo

Zeus as lover took many different

forms—in turn, a bull, eagle, swan, and a

shower of gold, but when he sought to get

it on with Hera, his predestined spouse,

transmogrified into a wet, weather-

beaten, affrighted, trembling, starveling

cuckoo bird: “a wise fable,” from, it’s said,

the “entrails of morality”—its guts.

The moral is this: in romance it’s wise

to avoid boastful tricks, which, to succeed,

call for dumb impressionability

in your beloved. S/he, if true-hearted,

is not to be won by conceited lies,

but rather by the tactics of inspired pity.

[1] Christopher Logue, Count Palmiro Vicarion’s Book of Limericks (Paris: Olympia Press, 1956), nos. 43, 163, 181.

[2] Christopher Logue, War Music: An Account of Books 1–4 and 16–19 of Homer’s “Iliad” (1981; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997, 24, 11. Logue died before he could finish this—War Music was his working title.

[3] Although naai (stich, or sew) is slang for “fuck” in Afrikaans, the homophonic verb “nigh” here is meant simply to convey the poetic sense of “to approach, or come near to.”

[4] Of dactylic hexameter it may be said that it works well in Ancient Greek, Latin, Hungarian, and Lithuanian, but not in English. Still, some have tried it, notably Arthur Hugh Clough in his 1848 tour de force The Bothie of Toper-na-fuosich, from part 1 of which this is a sample:

Bid me not, grammar defying, repeat from grammar-defiers

Long constructions strange and plusquam-thucydidëan,

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Crossing from this to that, with one leg here, one yonder,

So, less skilful, but equally bold, and wild as the torrent,

All through sentences six at a time, unsuspecting of syntax,

which explains the lachrymosity of McNamiter’s SO.

[5] “ . . . loquitur enim tanquam Republica Platonis, non tanquam in fæce Romuli,” Cicero writes in a letter to a friend of the Stoic Marcus Porcius Cato (95–46 BCE), called Cato the Younger (Cato Minor in Latin).

[6] See Sextus Propertius, Elegies 2.18A: 5–22: “Aurora didn’t allow him to lie there lonely in the House of Dawn. . . . Climbing into her chariot she spoke of the gods’ injustice” (www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/Latin/PropertiusBkTwo.php#anchor_Toc201112269).

Table of Contents

Peter Richard Dreyer is a South African American writer. He is the author of A Beast in View (London: André Deutsch), The Future of Treason (New York: Ballantine), A Gardener Touched with Genius: The Life of Luther Burbank (New York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan; rev. ed., Berkeley: University of California Press; new, expanded ed., Santa Rosa, CA: Luther Burbank Home & Gardens), Martyrs and Fanatics: South Africa and Human Destiny (New York: Simon & Schuster; London: Secker & Warburg), and most recently the novel Isacq (Charlottesville, VA: Hardware River Press, 2017).

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

3 Responses

Thanks for the titillating wit.

But what do you mean by “risqué” limerick? Ian that a tautology?:

The limerick is an art form complex

Whose subject runs chiefly to sex

It favors virgins

And masculine urging

And vulgar erotic effects

Not necessarily! Rico Leffanta writes, e.g.,

I’m stuck on this sidewalk alone

I can’t contact god with no phone

Confusing religion

No carrier pigeon

Why doesn’t god send down a drone?

The first known limerick was apparently chastely written by none other than Saint Thomas Aquinas in Latin (of course):

Sit vitiorum meorum evacuatio

Concupiscentae et libidinis exterminatio,

Caritatis et patientiae,

Humilitatis et obedientiae,

Omniumque virtutum augmentatio.