By John Broening (May 2018)

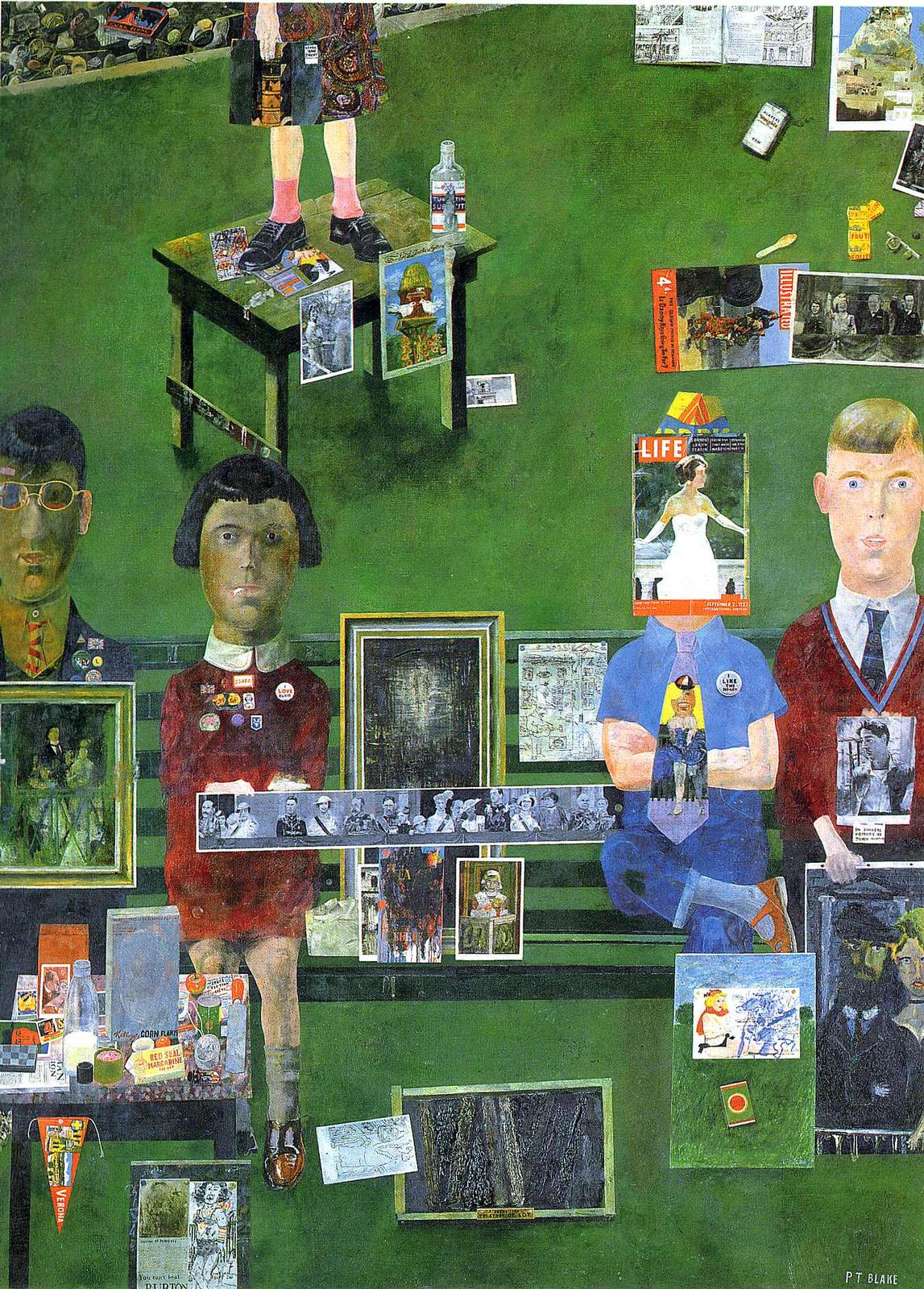

On the Balcony, Peter Blake, 1957

.jpg) an you create a work of art with little or no empathy? That’s easy. The answer is yes. The novels of Evelyn Waugh come to mind, in which there are few likeable or even vaguely sympathetic characters, in which death is a farce, filial love is an illusion, and romances are transactional unions between two dim, inattentive, and narcissistic people.

an you create a work of art with little or no empathy? That’s easy. The answer is yes. The novels of Evelyn Waugh come to mind, in which there are few likeable or even vaguely sympathetic characters, in which death is a farce, filial love is an illusion, and romances are transactional unions between two dim, inattentive, and narcissistic people.

Nietzsche wrote that a joke is an epigraph written upon the death of a feeling. He could have been thinking of a whole genre of dark comedy that includes Bierce, Mencken, Swift, Nathanael West’s The Day of the Locust. And any works by misanthropes like O’Neill, Goya, and Grosz.

To turn the question around, is there such a thing as an excess of empathy, and can it be a hindrance to the creation of a work of art? The writings of the journalist and essayist John Jeremiah Sullivan beg the question.

Sullivan is the most gifted disciple of David Foster Wallace. The tormented, cerebrotonic Wallace, who committed suicide in 2008, is probably the most influential American writer of the last twenty years. He once said in an interview:

Since an ineluctable part of being a human self is suffering, part of what we humans come to art for is an experience of suffering, necessarily a vicarious experience, more like a sort of “generalization” of suffering. Does this make sense? We all suffer alone in the real world: true empathy’s impossible. But if a piece of fiction can allow us imaginatively to identify with a character’s pain, we might then also more easily conceive of others identifying with our own. This is nourishing, redemptive; we become less alone inside. It might just be that simple.

After Wallace’s suicide, Sullivan published a tribute to the writer, an eerie work because, in its combination of earnestness and irony, of the grandly Latinate and the cozily slangy, it reads almost as if were written by the ghost of Wallace himself:

He didn’t want to be a total bummer, though; plus, it gave him something to say in interviews. In his books, so fluffy an idea would never survive the withering storm of panoptical analysis.

About his own writing, Sullivan said:

A source of energy and inspiration to me in my writing is empathy. I want to stay in touch with what I have in common with my subjects, with the places where are equally implicated with whatever is wrong with the culture. I feel more legitimate as an observer when I am in that place so I seek it out. I seek out subjects that plug into my own weaknesses and my own past.

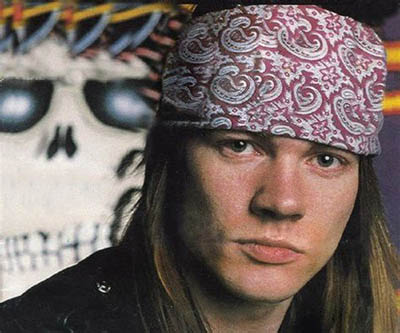

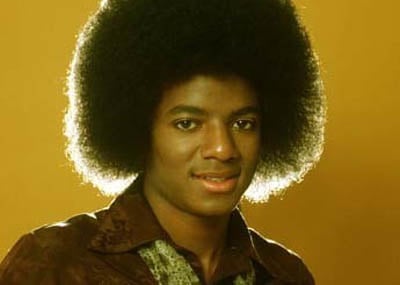

Here are some of the subjects Sullivan has tried to find common ground with: Christian Rockers; former reality TV stars; Tea Partiers (Sullivan is a liberal); the late emo rapper Lil Peep; animals, insofar as they have a consciousness; trash music mogul Simon Cowell; collectors of obscure blues records; fellow Indianian Axl Rose; fellow Indianan Michael Jackson; Venus and Serena Williams.

Wallace’s style, like Wordsworth’s, was a moral style that was concerned above all with honesty. Wordsworth rejected the Latinate conventions and formalisms of 18th century poetry in favor of common speech. Like a doorman checking for fake IDs, Wallace aggressively held up every word to extended scrutiny before letting it pass.

Wallace’s prolix style, full of qualifications, parentheses upon parentheses, footnotes, aphorisms as well as mumbling self-doubt, was meant to be true to the torrential, but also provisional and constantly self-emending, nature of thought.

The weakness of his work, though, was not stylistic but formal. Wallace never lost the showoff tone of the brilliant graduate student holding forth and his writing is full of paragraph-length sentences, chapter-length paragraphs. One of his novels, Infinite Jest, is the size of a small encyclopedia.

What Wallace has in common with many other geniuses—Faulkner and Joyce come to mind—is that he is more concerned with his vision than you-the reader’s-pleasure. Sullivan’s accomplishment is to take Wallace’s talents—his knack for finding unlikely but illuminating subjects, his extraordinary eye, his sedulous and creative research, his endless curiosity, his sly wielding of the common touch, his metaphorical nimbleness, his effortless ability to change and combine registers, and, yes, his empathy—and shape and discipline them. Sullivan’s writing is an example of the paradox that talent can be more satisfying than genius.

Why is he the way he is? That is the central question in most of Sullivan’s profiles. In “The Final Comeback of Axl Rose,” Sullivan goes to Lafayette, Indiana—the forlorn rustbelt childhood home of the notorious lead singer of Guns N Roses. Why, he asks, did Rose become not just the rebel singer of his generation but the star notorious for tearing up security guards, reporters, girlfriends, hotel rooms? The man who transformed himself from an androgynous youth to a creature of indeterminate age who looks like ”someone wearing an Axl Rose mask?” The unspoken but evident theme of the article is that Rose simultaneously imagines himself as the greatest rock star who ever lived and the most worthless piece of garbage who ever lived as well. Even after twenty years of stardom, he still can’t believe it. Like every avatar of cool, he carries his solitude with him in everything he does:

. . . he is doing ‘prance sideways with mike stand like an attacking staff-wielding ritual warrior’ between-verses dance. And after each line he is gazing at the crowd with those strangely startled yet fearless eyes, as though we had just surprised him in his den, tearing into some carrion.

Sullivan has the good fortune to find a thick cache of Rose’s old police reports, and every one of them is a Dirty Realist poem. A kid on a skateboard makes wheel marks all over his neighbor’s sidewalk. The neighbor and his mom get into it with the kid. The kid’s friend, Axl Rose—then Bill Bailey—shows up and begins beating the mom with his arm, which is in a splint. The splint, it turns out, came from holding onto an M-80 too long. You can’t make this stuff up.

Sullivan tracks down the kid, Dana Gregory who, after Guns N Roses made it big, had an unfortunate stint as Axl’s personal assistant, which meant “fixing shit that he broke.” Like a novelist would, Sullivan gets inside Gregory’s head for one of those bewildered how-did-I-end-up-here? midlife interior monologues:

The metamorphosis of Bill, the friend of his youth, in whose mother’s kitchen he ate breakfast every morning, his Cub Scout buddy (a coin was tossed: Bill would be Raggedy Ann in the parade; Dana, Raggedy Andy), into-for a while the biggest rock star on the planet, a man who started riots in more than one country and dumped a supermodel and duetted with Mick Jagger and then did even stranger shite like telling Rolling Stone he’d recovered memories of being sodomized by his stepfather at the age of two, a man who took as his legal name and made into a household word the name of a band (Axl) that Gregory was in, on bass, and that Bill was never even in, man . . . This event had appeared in Gregory’s life like a supernova to a prescientific culture. What was he supposed to do with it?

Sullivan, who grew up in Indiana, in that shabby-genteel class that has produced so many good writers (his father was a failed sportswriter), recounts his own experience with boys of Axl’s background, childhood playmates he grew apart from.

Like Lilian Ross’s famous profile of Hemingway, or Truman Capote’s The Duke in His Domain, it is a portrait of a trauma in motion and uses the techniques of the novelist to make the subject come to life. But, unlike either of these, “The Final Comeback of Axl Rose” is not a takedown. It gives Rose the benefit of every doubt, musically and otherwise (to my mind his voice, which once had that tight, controlled vibrato and incomparably powerful high end, has declined alarmingly and has long been propped up with engineering effects). It is a profile that the subject would probably approve of.

In “Michael,” written shortly after Michael Jackson’s death, Sullivan proposes, tortuously, ”of all the things that make Michael unknowable, thinking we knew him is maybe the most deceptive. Let’s suspend it.” In other words, Sullivan offers a kind of revisionist biography. Michael, as he calls him throughout, might not have been the creepy, weird person we imagined him to be, the prototypical self-destructive, self-hating former child star. Sullivan listens to the homemade demos of what would become world-famous songs; he reads Michael’s interviews in Ebony and Jet; he traces Michael’s ancestry back to the days of slavery; he takes a very close look at signature performances. What he sees—and to his credit he doesn’t push any of his suggestions too far and hedges his bets with perhapses and maybes and could have beens—is a much more self-aware artist and man than we are used to imagining.

Sullivan describes the growth of Michael as an artist in the free, indirect style that a novelist would use:

His eldest brothers had at one time been children who dreamed of child stardom. Michael never knows this sensation. By the time he achieves something like self-awareness, he is a child star. The child star dreams of being an artist.

The albums he and his brothers make have a few nice tunes, to sell records, then a lot consciously second-rate numbers, to satisfy the format. Whereas Tchaikovsky and people like that, they didn’t handle slack material. But you had to write your own songs.

When he’s seventeen, he asks Stevie Wonder to let him spy while “Songs in the Key of Life” gets made. There’s Michael, self-consciously shy and deferential, flattening himself moth-like against the Motown studio wall. Somehow Stevie’s blindness becomes moving in this context. No doubt he is for long stretches unaware of Michael’s presence. Never asks him to play a shaker or anything. Never mentions Michael. But Michael hears him.

Sullivan reexamines interviews with Michael in old issues of Ebony and Jet:

The articles make me realize that about the only Michael Jackson I’ve ever known, personality-wise, is a Michael Jackson who’s defending himself against white people who are passive-aggressively accusing him of child molestation. He spoke differently to black people, was more at ease. The language and grain of detail are different. Not that the scenario was any more journalistically pure. The John H. Johnson publishing family, which puts out Jet and Ebony, had Michael’s back, faithfully repairing and maintaining his complicated relations with the community, assuring readers that, in the presence of Michael, “you quickly look past the enigmatic icon’s light, almost translucent skin and realize that this African-American legend is more than just skin deep.”

In hushed tones, Sullivan looks at the famous “moonwalk” video from the Motown 25th TV show:

I won’t cloud the uniqueness of what goes next with words except to mention one potentially missable I because it’s so obvious) aspect: that he does it entirely alone.

About Michael’s pedophilia, multiple settlements, arrest, trial and vilification, he writes in provisional, thickly qualified language:

But when you put on the not-so glasses and watch, and see Michael protesting his innocence, asking “What’s wrong with sharing love?” as he holds hands with that twelve-year-old survivor . . . There appears to exist a nondismissable chance that Michael was some kind of martyr.

Sullivan’s conclusion, part rant, part eulogistic peroration:

We can’t pity him. That he embraced his own destiny, knowing beforehand how fame would warp him, is precisely what frees us to revere him.

We have, in any case, a pathology of pathologization in this country. It’s a bourgeois disease, and we ought to call bullshit on it. We moan that Michael changed his face out of self-loathing. He may have loved what he became.

Ebony caught up with him in Africa in the 90s. He had just been crowned king of Sani by villagers in the Ivory Coast. “You know I don’t give interviews,” he tells Robert E. Johnson there in the village. “You’re the only person I trust to give interviews to”:

Deep inside I feel that this world we live in is really a big, huge, monumental symphonic orchestra. I believe that in its primordial form, all of creation is sound and that it’s not just random sound, that it’s music.

May they have been his last thoughts.

It’s hard to know what to think of this. It’s tempting to call bullshit on it right away, but the roots of its egregiousness are so tangled that maybe we should look at those first. Michael’s tragedy may be a racial tragedy, but its outlines are more recognizable as a show biz story, or a show biz tragedy.

It is a racial tragedy not just in that Michael was committed to destroying his perfectly pleasant and attractive negroid features. It is also a racial tragedy in that more than a few of the agents of his oppression were themselves African-American: Berry Gordy, the former pimp turned record mogul; and many of the members of Jackson’s own family—who both envied and bullied him and saw him as a meal ticket, most of all his father, Joe.

Joe Jackson makes me think of an anecdote that A.J. Liebling tells, about an old vaudevillian, a clown, who raises his son to be a clown, but first breaks his legs so he will naturally walk funny.

Like his friends—all of them at one point child stars—Liza Minnelli, Liz Taylor, Emmanuel Lewis, Macaulay Culkin, and Brooke Shields, Michael Jackson’s deepest wish was to be a member of the rarefied domain of Pure Show Business. In America, race tends to trump everything, but in the world of Pure Show Business, nothing is more important than fame and pedigree.

The world of Pure Show Business values eccentric artifice above naturalness and authenticity. Its hallmark is not just natural talent but the expression of a free-floating kind of individuality.

Look at this video of Anthony Newley performing ‘Who Can I Turn To?’

The first thing you notice is Newley’s rich, agile, well-trained baritone. Newley was, like Jackson was, a trouper from an early age, a skilled singer, dancer, and actor. The next thing you notice is those weird Chaplin-like gestures and the highly mannered phrasing and diction (especially in his vowel sounds). Then watch at 4:19 when, after the performance, Newley’s boss David Merrick shows up in the audience. Watch Newley’s fulsome Pierrot like reaction.

Now watch these two videos of the song “Shake Your Body (Down to the Ground).” The first, from the late Seventies, is a live performance with the Jacksons, lip-synched to the Jacksons’ record. What you notice it that it has an irresistible piano-based mid-tempo-to-fast groove. You hear those characteristic high grunts and percussive whoops that Michael borrowed from Jackie Wilson. You also get a sense that Michael is pantomiming the pleasure and delight in dance and movement that is what the song is about.

Now watch this solo Michael Jackson performance from the late 80s.

The tempo is furious, frantic and undanceable. If you didn’t know better, you would think that everyone, including Michael, was coked-up. But what’s clear in this performance, and every Michael track from the early 80s onwards, is that there is a disconnect between the expressive content of the song and the singer’s performance. There is a kind of mannered feral intensity in all of Jackson’s performances and recording that is Pure Show Business.

Even in the famous Motown 25th performance of ‘Billie Jean’, the same thing is at work.

In the singing, the grunting and whooping is more insistent but the delivery is only tenuously related to the emotional content of the song. As for the famous dance, it is justly celebrity for its inventiveness, explosiveness and athleticism but, like the Jacksons’ singing, it has little to do with the song. Does this matter? If you look at Fred Astaire’ s dancing (and Jackson was often compared to Astaire), it’s always in service to the song. Astaire dances ballads elegantly and romantically, he does plucky tunes like ‘Pick Yourself Up’ with a combination of beautifully feigned clumsiness and mock-determination, he does ‘blackface‘ tributes like ‘Bojangles of Harlem’ with appropriate swagger and a unique independence between the top and bottom halves of his body.

The good fortune that Michael had was that his empty intensity coincided with a change in the culture. The eighties were all about the big hollow gesture-think of those big echoey drums in every pop song of the decade and Michael, more than anyone, profited from his skillful deployment of this new manner.

But back to Pure Show Business. If you look at some of the actions Sullivan praises as examples of Michael’s courage, clear-sightedness and unknowability, if you scrutinize them through a kind of show-biz derived Occam’s Razor, they start to look different.

If, as Sullivan breathlessly writes about the Motown 25th performance, “he does it entirely alone,” well, this is not an exactly a courageous act for a born performer; it is the state of affairs. They always strive to be entirely alone, without having to share stage with anyone.

As for those candid interviews in which ”the language and the grain of detail is different,” from the perspective of Pure Show Business, they read like the tailored expressions of a veteran who has been doing meet-and-greets since he was six years old, telling his fans what they want to hear.

The scandals that clouded Michael’s last years. It’s hard to know what to say about them. Except that the sad question is not whether Jackson was a pedophile, but whether he was a practicing one.

The serious question at the heart of Sullivan‘s writing has to with the limits of empathy. It’s serious because it is a question that touches not only writing but political philosophy. In every political philosophy there is a core sentimentality. In conservatism, it is the belief that things were better in the past, and that this Golden Age more often than not coincided with the childhood of the conservative thinker. In liberalism, the core sentimentality is the belief in the supremacy of empathy, and its corollary, that the oppressed and the suffering have not just a certain moral authority (something that even some conservatives might agree with) but that they have an innate moral superiority.

But do they? And should they? As B.R. Myers noted in a review of Toni Morrison’s Mercy:

Perhaps this tendency to idealize the exploited is part of our literary tradition as a whole. Where the European writer condemns poverty for bringing out the worst in people, the American condemns it for oppressing such fine and decent folk; compare Germinal, say, with The Grapes of Wrath. Morrison, too, is so busy showcasing her characters’ nobility that we get little sense of what hardship can really do to the human spirit.

Behind the elevation of empathy is something like a mother’s special pleading, a request for the suspension of universal principles and moral laws. And who can resist a mother’s entreaties?

_________________________________

John Broening is a freelance writer based in Denver, Colorado. His writing has appeared in Gastronomica, Departures, The Baltimore Sun, The City Paper, The Faster Times and The Outlet and his article on the Noble Swine Supper Club was featured in Best Food Writing 2012.

More by John Broening.

Please support New English Review.

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link