by Matthew Walther (September 2012)

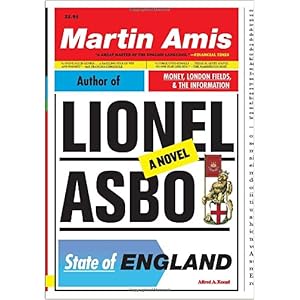

Lionel Asbo: State of England

by Martin Amis

Alfred A. Knopf. 255 pp.

In his thirteenth novel, Lionel Asbo: State of England, Martin Amis’s fiction appears to have reached what Henry James, in reference to Dickens’s Our Mutual Friend, calls “permanent exhaustion.” The author, apparently bored of “computer fugues, Japanese jam sessions, didgeridoos,” has tried his “long-practiced hand” (to employ another Jamesism) at broad comedy. The result? A novel that resembles nothing so much as a sitcom version of Theodore Dalrymple’s Life at the Bottom run to its eighth or ninth season. What has happened to the author of Money and Time’s Arrow, a critic who has produced some of the most incisive and entertaining essays, articles, and reviews of the last half century? Run out of steam? Juice?

Lionel Asbo (whom Jess Walter of Publisher’s Weekly identifies with Abel Magwitch, much to that good man’s detriment) is a tattooed bruiser who lives with his nephew Desmond in a council estate. While Lionel takes drugs, commits burglaries, and trains a pair of “psychopathic pitbulls” to assist him with the goon work, Desmond pursues schemes of intellectual improvement, e.g., learning words from the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary by rote. In the first of the novel’s four sections, the only situation resembling a crisis occurs when Desmond begins sleeping with his grandmother. Lionel rightly suspects that his mother (who is only 39) has taken a lover, and, with the toneless thundering of a typical underclass Othello, vows to revenge himself upon her companion (“‘My mum some GILF? No. My mum some bonking biddy? No.’”). But nothing ever comes of it. It turns out that Gran, unbeknownst to Desmond, has begun offering herself to one of his classmates, Rory Nightingale, whom Lionel promptly murders. Incest and murder are two partners that no novelist can afford to dance with idly. Yet Amis treats them with zero gravity, less than zero, so unseriously, with such complete nonchalance that my brain refuses to process whole stretches of Lionel Asbo. I say this not because Amis approaches these sordid incidents with unbecoming levity: levity, as opposed to indifferent reporting, would be welcome. Words on a page: nothing more.

Now about Lionel’s surname: he chose it, you see, at age 18, as a kind of loving tribute to the Anti-Social Behaviour Order that he received at age three. Fair enough, and I’m sure stranger things have been done at registry offices. But there is a problem here, namely, that even if little Lionel were issued his very own ASBO the first year they were introduced as an alternative to criminal prosecution by the Blair government, that is, in 1998, then he must have been born no earlier than 1995, making him, in 2008, at most aged 13 years. Yet, according to Amis, he is 21. Why do I mention this? Because it suggests that, contra most critical received wisdom, Amis has little time for details. (Compare this with his father Kingsley Amis’s precise choice of Leicester as Dixon’s alma mater in Lucky Jim: the university was established in 1921, giving Jim 33 years, plenty of time, to have earned his degree, served in the War, and begun teaching.) Such imprecision is also evidenced by Amis’s use of free indirect speech, which he sometimes choses to indicate via italics, but which elsewhere appears in Roman type. Hoping to uncover some kind of Faulknerian logic behind Amis’s apparently erratic typographical decisions, I noted every instance of free indirect speech in Lionel Asbo: to no avail.

It is in the second part of Lionel Asbo that Amis’s title character wins £140 million, enabling him to drink champagne from pint glasses, eat caviar with ketchup, hire a talent agent, and get kicked out of London’s plus cher hotels. The grotesque episodes that follow are sometimes amusing (though rarely for more than two or three pages at a time), as in the following in which Lionel, a chain cigarette smoker, starts in on one of his first havanas: “Lionel lit a fresh cigar (and proceeded to smoke it as he would a Marlboro Hundred, with long drags and emphatic inhalations).” In this section it becomes clear that the ratio between Lionel’s comic potential and what Amis manages to achieve with him is maximally high. (I imagined Lionel being made, by some absurd vicissitude, a Life Peer and becoming the first person to sit in the House of Lords for the British National Party. From a hypothetical Question Time appearance: “I fink Peat-uh Itchins ees a noice chap. But uh-bout drugs, ees dead wrong. Sat simple, mate.”)

In the second section of Lionel Asbo we are also introduced to Desmond’s girlfriend and eventual wife Dawn. In a scene in which Amis makes a fairly dull go of portraying him as a half-witted bigot (cf. the cab driver in Money), Dawn’s father disowns her. (Desmond, we learn halfway through the novel, is half Trinidadian.) If Lionel is a “mere bundle of eccentricities, animated by no principle of nature whatever” (James again!), a mess of blottings and smudges that, examined none too carefully, in no way resembles a human being, then Dawn, his polar opposite, is an unfinished pencil sketch, a collection of thin grey lines. Amis does not describe her. She has no interesting dialogue, thoughts, or actions. Compared with Dawn, Ayn Rand’s Lillian Rearden is Rosalind or Anna Karenina. Amis has never been quite comfortable with his female characters, and for good reason: they are almost invariably harpies, porno-type molls, or women asking men to murder them. Asking him to imagine women more worthy of the reader’s sympathy than, say, Selina in Money or Cora in Yellow Dog and more intriguing than Dawn is not exactly a squaring-the-circle sort of request.

I have written more than 1000 words about Lionel Asbo without saying anything about Amis’s prose style. Nothing about the novel is stylistically remarkable. Mostly gone are the lists, the asyndeton, the slang (save in dialogue), and the other well-known Amis tics. The “terrible compulsive vividness,” about which Amis’s father complained but which, for good or ill, has always been Martin’s sole claim upon his readers’ attention, is nowhere evident. Some prose samples: “Minutes later Des reeled down the infinite staircase with Jeff and Joe.” “Dawn woke him—no, not his wife. Eos—Eos woke him: daylight woke him.” “As he was finishing off with Dylis, he happened to glance sideways at the closet mirror.” “The room was the colour of beetroot, thickly dark but with a shade of mauve in it.” Here is prose that is virtually colorless: unoriginal but not quite bromidic; too spiritless to invite underlining, but too twee to be called plain; far from flashy, but not, never, casual.

All of the above would almost be excusable, even for Martin Amis, if Lionel Asbo were not flawed in so many other ways. On the other hand, had Amis managed some of that old black prose magic—the post-human magic!—that made even Night Train worth reading slowly, perhaps one could forgive him for having said nothing insightful or edifying. But sans the chichi prose, Money and Yellow Dog offer the reader—what? Feculence and amorality? What about life, human life, humanity?

Once more, James: “The word humanity strikes us as strangely discordant, in the midst of these pages; for, let us boldly declare it, there is no humanity here.”

Matthew Walther is an American writer.

To comment on this book review, please click here.

To help New English Review continue to publish interesting and timely articles such as this one, please click here.

If you enjoyed this article and want to read more by Matthew Walther, please click here.

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link