by G. Murphy Donovan (February 2021)

Feast in the Garden, Corneille, 1971

I cook with wine. Sometimes I even add it to the food. —W. C. Fields

Umami is one of those words, like love, that seems to defy precise definition. Just as love is often confused with sex, umami is just as often confused with taste, worse still, good taste.

Indeed, taste itself is another one of those rabbit holes in the English language. You are apt to have a taste for football and a hot dog at the same time, one a sport and the other a savory snack. The agents of engagement couldn’t be more different, feet for the first, your cake hole for the latter. The ambiguity of English words is a testament to various flavors of language, a groaning board of meaning indeed.

Indeed, taste itself is another one of those rabbit holes in the English language. You are apt to have a taste for football and a hot dog at the same time, one a sport and the other a savory snack. The agents of engagement couldn’t be more different, feet for the first, your cake hole for the latter. The ambiguity of English words is a testament to various flavors of language, a groaning board of meaning indeed.

Reason or science dictates that you consult a dictionary for unambiguous clarity:

“Umami” is a pleasant savory taste imparted by glutamate, a type of amino acid, and ribonucleotides, including inosinate and guanylate, which occur naturally in many foods including meat, fish, vegetables and dairy products.”

Clear enough? Five obscure nouns followed a buffet of comestibles. If etymologists stopped with “pleasant savory taste,” the definition of umami might be clear yet still inadequate.

Surely, umami is a matter for the heart not the head.

Taste itself is arbitrary, a cultural preference or just one of five senses that include, in addition to taste, sight, sound, smell, and touch. Surely, at least three of the remaining four are as important to umami as taste is. What is sushi, or any presentation, without sight? How do we appreciate aroma without smell? How is al dente a thing without touch or bite?

We do a lot of fun things with our tongue, teeth, or lips where eating is not even the main event.

Sound might be an umami long-shot, but not if we include crunching, gnawing, lip smacking, and belching.

The most important, if not useful, sense excluded by science and etymology from the big five is usually common sense.

Indeed, all human sensory portholes are arbitrary and subjective. What you or I appreciate about the same dish or meal may not be the same experience.

And let’s not use savory as a synonym for umami. Savory is settled law in the culinary code, as in “not sweet.” By that definition, a fresh warm steaming meadow muffin is savory, but not necessarily umami.

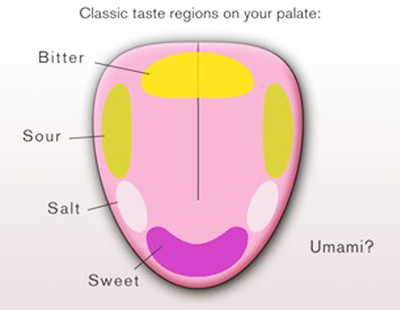

The rabbit hole gets deeper if we do some forensics on taste, as in your mouth; which for thorough analysis apparently requires a tongue map.

Sadly, palate maps don’t cover; hot, cold, jalapeno, disgusting, or gag-a-maggot either. Thus, a precise understanding of taste by mouth is elusive too.

Sadly, palate maps don’t cover; hot, cold, jalapeno, disgusting, or gag-a-maggot either. Thus, a precise understanding of taste by mouth is elusive too.

Tasty to you might be gross for me.

Take pearl onions, a culinary scar from my childhood. When the slipery mini balls appeared on my aunt’s holiday table, I asked my older sister what they were.

“Eyeballs,” she hissed without missing a bite. To this day, I cannot abide a plate of pearls.

Culinary emotions are a thing, especially as in love of or hate for.

A better example than onions might be had with beef, let’s say steak tartare (raw ground filet, raw egg, lemon, Worcestershire sauce, mustard, salt and pepper) compared to broiled Delmonico.

Both are quality cuts from the same critter.

Raw minced meat had its origins with the Crimean Tartars; so given to battle that they were loath to leave the saddle long enough to cook or dine unhorsed. For sustenance, Tartars carried a dollop of raw ground meat under their saddle; betwixt sweaty arse, leather, and wet horse.

Imagine the umami when doing lunch at a gallop.

Steak tartare was consumed raw then, just as it is at the French Laundry today, minus the horse sweat and saddle soap we pray.

Delmonico, a boneless center cut of rib-eye, appeared when tables and ovens made their debut in New York. Unlike steak tartare, a cut of marbled rib-eye is cooked, not minced, usually broiled with a minimum of condiment abuse.

Carmalized beef fat is the secret to a good burger as it is for a good Delmonico. When Jimmy Buffett claims that there will be cheeseburgers in paradise, he speaks to heavenly Umami, in this case a product of scorched dairy and animal fats.

Whilst we dwell on the rib-eye we should mention that umami apparently has a martial component too. Take the “tomahawk steak,” a beef medallion attached to 18 inches of rib bone.

Weaponized diner or dinner, your call.

For the moment, let’s agree that umami, like love, is an exotic, sometimes erotic, experience that only exists on the tounge, in the eyes, or in the heart of the beholder.

Indeed, at this point, some might argue that umami is purely an emotional experience, alas the deepest hole yet. The psychobabble of feelings is, alas, more black hole than rabbit warren.

Science and psychology argue that human emotions range from eight in number to infinity. Aristotle said there were only nine. UC Berkeley says there are 27. Bob Plutchik says there are eight basic emotions which subsume a host (24) of related lesser feelings.

Assaying the emotional components of umami, beyond love and hate, might be like trying to count fruit flies on a ripe melon. Plutchik’s pinwheel of sentiments might have, to be beleivable, included feelings like queasy.

.jpg) We may just have to accept that umami is, as an experience, lovely but not necessarily orgasmic. The Japanese sense of the word probably implies ingredient and flavor restraint, a variety of textures, a palate of color, and an artful arrangement; in short, a pleasant and wholesome bite or meal.

We may just have to accept that umami is, as an experience, lovely but not necessarily orgasmic. The Japanese sense of the word probably implies ingredient and flavor restraint, a variety of textures, a palate of color, and an artful arrangement; in short, a pleasant and wholesome bite or meal.

The quest for umami, like love, is very personal and not without a few bumps in the road.

You should be alarmed if your husband or wife puts ketchup on hot dogs. Odd and disturbing, yes, but not necessarily a reason to call your lawyer. Like drinking Merlot, inappropriate condiments or beverages might just be a residue of progressive potty training, Montessori, or public-school lunches.

Life, love, insight, and umami are all long journeys where all those miles are much shorter with two on the road.

__________________________________

G. Murphy Donovan is a veteran of the Bronx who worked his way through high school and college in kitchens and dining rooms—long before he set a table for the deep state.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link