by Justin Wong (September 2022)

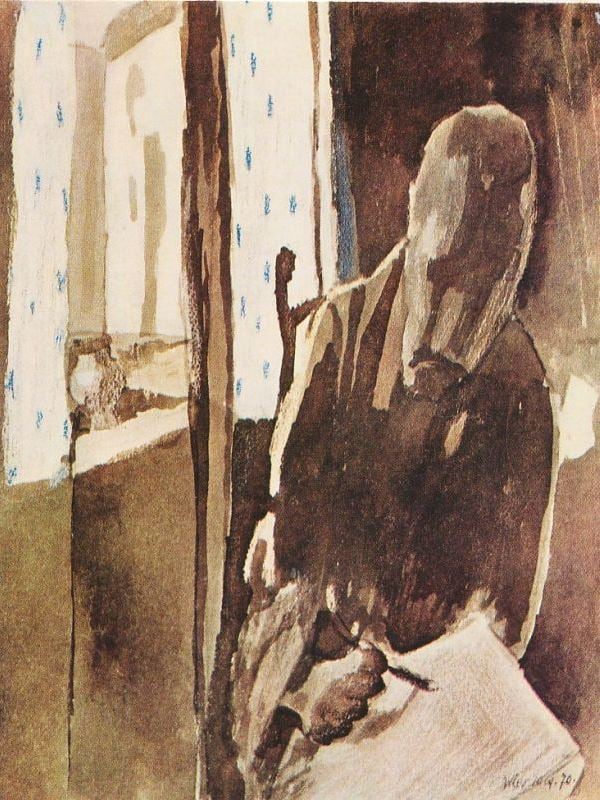

Artist at the Window, Paul Klee, 1909

I have spent a great deal of my life engaged in creative life, and it is something that I have desired to spend my time doing since I was a teenager. This hasn’t always included the writing of poetry and stories—when I was a teenager, I was deeply immersed in music. I thought for a while that I wanted to be a musician of some kind or another. I played the piano, the guitar, and produced music on the computer in my bedroom. There was something about all of this I found to be quite unsatisfying, even if I still have a deep appreciation for music. There is something about the music industry that seems to be incredibly corrupt. It was then as it is now, concerned with the creation of hype and fads that change from year to year. Often at times, a musician’s career is finished before there is a chance for it even to develop.

It was in my teenage years that I enflamed my love for literature. My parents weren’t big readers, although books were always around in my house when I was a child. My first experiences with books were more or less the usual fare, which included the Chronicles of Narnia, the Wind in the Willows, and the children’s novels of Roald Dahl. I didn’t spend a lot of my free time reading, because the act of reading wasn’t presented to me as something that you would spend your free time doing for pleasure, but as a form of punishment. The thought that reading could be enjoyable was something I discovered relatively later on in life.

When I was around the age of fifteen, I remembered reading To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee, and thought that it would be the most wonderful thing in the world to write the kind of book that touched so many people. Although this kind of popularity and critical acclaim, where the novel contributes a part of the cultural dialogue were rare at the time of its publication, and virtually non-existent now. The majority of the books that I have read in the interim of my reading life that I have found deeply moving, have not had this kind of popularity or adulation. One could also say that the majority of books that have been published to great success, or critical acclaim have more often than not, been trivial.

There used to be a distinction between the kinds of books that the public were immediately drawn to, and what a more discerning critical establishment thought were worthy of being read. Book critics once judged works on their aesthetic value, difficulty, and complexity, although they now seem to universally judge books on how much they parrot the dominant creed of political correctness. Publishers are not much different, and thy only publish works that conform to a particular worldview.

***

I continued on with my love of reading, consuming many classic and contemporary works. This also sparked an interest in other things, such as philosophy. Although the more philosophy I read, the more I thought that this field was a more inferior way of presenting truth to the world than literature.

After this came my first attempts at literature, which were more or less rudimentary, as all preliminary attempts at writing are. The more I plugged away at this, I eventually had bits and pieces published. This was not to the kind of fame and fortune that I desired, but nevertheless I didn’t stop. Many people would say that I was wasting my time being engaged in this kind of pursuit, and maybe they are right to think this. Writing is, to most people who do it, a vain and fruitless endeavour. But this is not the same thing as saying that it doesn’t have meaning.

I say this as the more I managed to write, the happier I managed to become. My working on a poem, a novel or a story was something that was more or less a pleasurable experience, but it was the kind of pleasure that transcended mere enjoyment and began to heal many of my neuroses, and the stresses that were known at times to plague me. In previous moments in my life, I went to counselling, and to the extent to which this helped me, it was marginal. When writing became a regular part of my life, I felt that it had a therapeutic benefit. Before I wrote certain things, I was one way, and after I wrote them, I was someone else.

***

If one were to ask what it was exactly, that I got out of reading or writing, the only answer I could give, was pleasure. This may make it seem trivial and fleeting, but most people assume pleasure to be a primarily base thing that stimulates the body as opposed to the mind, such as drugs and sex. Although John Stuart Mill described the pursuit of wellbeing as consisting of what he termed, higher pleasures, that is “pleasures of the intellect, of the feelings and imagination, and of the moral sentiments.”

The act of writing might have always begun in enjoyment, but it had the potential to lead to transformation, even if this rarely happened. This was far from leading me to fame and fortune, but it was scarcely insignificant either.

The fact that writing in general doesn’t form part of the cultural dialogue in ways it perhaps should in a healthy society, didn’t much matter. There were of course other benefits to it. The French composer Arthur Honegger once said, “The modern composer is a madman who persists in manufacturing an article which nobody wants.” He also said, “The public doesn’t want new music; the main thing it demands of a composer is that he be dead.” The great irony of artistic creativity is that the public realise the value of a work when it is too late to actually benefit the creator.

We are often told that if we work hard in life, that we will be rewarded for our efforts, but if anything, this law is inverted in the world of art. Apart from certain exceptions, the artist’s work benefits everyone aside from himself. James Joyce, considered by many to have created the finest novel of the 20th century, lived much of his life in poverty, although a letter of his was sold at auction in 2004 for £240,800, which did nothing to benefit Joyce and his family. A similar story could be told of his friend Samuel Beckett, whose manuscript of his first novel, Murphy, was rejected 40 times by publishers, before being taken up by Routledge. The manuscript for this novel went for £962,500 at auction in recent years.

To say that the field of literature, or art in general, operates through parasitism, is grossly unfair to parasites. Parasites feed off their hosts, whereas in artistic fields, they are far fatter than the people whom they feed off of. Artists tend to give far more to society than they receive, and in return are vilified in their day. This isn’t to say that all of them are memorable, and the majority of what is created falls to the wayside.

Although one only has to look at William Blake who was largely overlooked in his day and age, to see that he has suffered a kind of injustice. His Songs of innocence and Experience has been widely influential in the years after his death. It has been set to music by various composers and musicians, and has been studied widely in the field of academia. His art and poetry have formed an integral part of English culture, although his book Songs of Innocence and Experience only sold 20 copies in his lifetime. Why should this be so?

In Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, he says that the Owl of Minerva flies at dusk. This is the spirit of wisdom that makes itself known only after a finality. We are perhaps able to see the genius of an artist when their critiques and prophecies of their time have proved to have been right. Which coincidentally happens to be at the moment when it ceases to benefit them.

This is a law that is true not only in fields of creative endeavour, though in much of life. In the Bible, Moses dies before he sees the promised land, yet the people he led there did get to see it. The people who create great movements, very rarely get to see the fruits of the labours. This was also true of abolitionist William Wilberforce, who died three days after his twenty-year campaign to end slavery.

Art concerns itself with breaking demystifying many of the illusions of the age, in which many of the public are beholden to. With this understanding, it is not surprising that much bad art is glorified in its own time and forgotten later on. People like it, not because it has something contrary to say, but because it is able to reflect many of the lies and illusions that are common in its place and time.

Despite my realisation of this contradiction in literary fame, I carried on writing and immersing myself in this pursuit. The possibility that I should be famous in this field, would be slim to none. I felt this way, only because I had an abiding passion for literature, whether reading and writing.

There is also the notion that people write because they have something important to say. I always thought that this was the motivation for my wanting to write. Many people have been engaged in intellectual pursuits because they have something new to say to the world. I don’t think I have any new visions of how I desire the world to be, this is one thing that I find excruciating about intellectuals. Much death and destruction, famine and the spread of disease have been the result of people who want to remake the world in their image. The spirit in which I write is more critical, in the sense that it wishes to break through the lies and the illusions of the age. I don’t think I can necessarily plumb new depths of human potential or lead my fellow man into a glorious new world, as so many other writers and thinkers have sought to do before me. One only has to look at the twentieth century to know that the naïve desires that men have to create Utopia, more often than not bring about the opposite effect. Instead, my motivation was always to point people to what was already there.

One of my favourite movies is called Hallelujah, which was made in 1929, and tells the story of its main protagonist Zeke, a righteous man who gets seduced by the wrong kind of woman which leads to him to murder. The film could be classified as a comedy, seeing as it has a happy ending. Although the strange thing is that Zeke’s life is no more elevated at the end of the film then it is at the beginning. It is the same in every way except he is now able to see the value of what he had in a way that eluded him at the story’s opening. In this sense the film has the pattern of the Prodigal Son narrative, which is echoed throughout the Bible.

This is perhaps what I wish to achieve in writing, to make people see the value of the thing that they are so dead intent to run away from.

Justin Wong is originally from Wembley, though at the moment is based in the West Midlands. He has been passionate about the English language and literature since a young age. Previously, he lived in China working as an English teacher. His novel, Millie’s Dream, is available here.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

One Response

Well said. I’ve long felt that miracles erase themselves and that it is the duty of artists of all stripes to revivify our existence. There is so much of life to be revivified, that it is good there are so many of us. It’s a pleasure for the artist to just hammer and pound what we have into what matters.