by Pedro Blas González (March 2022)

The Ruger art collection, now boasting more than 215 paintings and about two dozen drawings, rivals that of most museums. Concentrating primarily on American artists, the range is wide, although the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: Winslow Homer, Alexander Pope, Frederic Remington, Charles Marion Russll, Christian Schussele, Oscar E. Berlinghaus, Alfred Jacob Miller…and more.

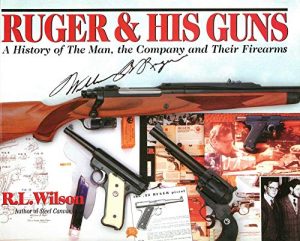

– Ruger & His Guns: A History of the Man, the Company and Their Firearms.

William B. Ruger was an American industrialist and industrial designer, a man with a penchant for precision craftmanship, who along with Alexander McCormick Sturm, created Sturm, Ruger & Company in 1949. At that time, Colt, Winchester, Smith & Wesson, Remington, and Browning dominated the firearms industry. William B. Ruger was born on June 21, 1916, in Brooklyn, N.Y. Ruger received his first firearm, a Remington .22 pump action rifle from his grandfather.

Sturm, Ruger & Company

While the focus of this essay is William B. Ruger’s impressive art collection, a measure of attention must be paid to Sturm, Ruger & Company.

Sturm, Ruger & Company created and developed some of the most iconic and reliable firearms in the world during the second half of the twentieth century. This is significant because Sturm, Ruger & Company had to compete with companies that had been established many decades before.

While there are many high points that must be mentioned about Sturm, Ruger & Company, a few highlights are essential to showcase the fine reputation of this solid American company.

Sturm, Ruger & Company was founded on the creation of its now classic .22 caliber Mark I pistol. This was the first pistol in which the bolt moved inside a tubular receiver. Sturm, Ruger & Company developed sights that remained stationary when firing; the first firearms to use pressed and welded steel grip frame components; pistols equipped with an integral laser sight housing.

Some of Sturm, Ruger & Company’s classic firearms include the .22 caliber Mark series pistols, Blackhawk .357(Maximum, Magnum caliber), Super Blackhawk .44 Magnum caliber, GP100 double-action revolver, .44 Carbine centerfire rifle and the Red Label 20-gauge shotgun.

Art Collecting

William B. Ruger’s art collection is exquisitely displayed in After the Hunt: The Art Collection of William B. Ruger by his granddaughter, Adrienne Ruger Conzelman. To a lesser extent, this is also true of R. L. Wilson’s impressive and picturesque biography of William B. Ruger: Ruger & His Guns: A History of the Man, the Company and their Firearms.

What makes Ruger’s art collection exquisite is that it reflects the taste of the cultivated man behind the collection, not market forces and the timely fashions that the art world is so willing to embrace and promote. Tom Wolfe best describes this fake world and affectation in Radical Chic & Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers.

As an avid art collector, Ruger had a heightened aesthetic sensibility. This cannot be said of many art collectors. Ruger’s collection totals more than 200 works of American and European art. While the Ruger art collection represents works that are catalogued as Western art, it is not limited to American artists and works of art.

It is difficult to focus on just a few of Ruger’s paintings that appear in After the Hunt. I will emphasize four: After the Hunt (1879), Two Hunters & Canoe (1911), Sentinel of the Plains (1906) and Maynard Dixon’s Cloud World (1925).

William B. Ruger was a collector who had a keen eye for aesthetic merit and life-affirming subject matter. The paintings in his collection are uplifting, aesthetically and in their subject matter. Most important, Ruger acquired paintings that he liked. It is evident in his collection that Ruger eschewed the fashion-seeking route to art collecting, which more often than not, is a road paved with artificiality.

The art world, whether through artists or art collectors, comes replete with fakers, afficionados of the trendy – people who can’t see beyond the fashionable. The temptation to collect works by artists who are trendy is detrimental to genuine artistic and aesthetic sentiment because it reduces the potential expression of the sublime and transcendence that art can bring to light to the banal and mundane. This has never been truer than in postmodern art.

Today, the greatest offenders are the alleged art collectors – who ordinarily – are people who have more acquisitive power than sense and aesthetic sensibility.

After The Hunt

After The Hunt is a painting by the American artist Levi Wells Prentice (1851-1935). The subject matter of the painting is five men huddled around a campfire in their camp by a lake. They are hunters. Their rifles and animal furs are on display. After the Hunt likely takes place in the Adirondack mountains. When Prentice painted After the Hunt he lived in Syracuse.

Prentice’s acute attention to detail is a testament to working directly in nature. While the five hunters who appear on the right side of the canvass are the subject of the painting, a closer inspection reveals that it is the unspoiled woods that take center stage.

The campfire lights up the men’s faces and their makeshift shelter, thus directing the attention of the viewer to the right side of the work. High on the left side of the painting, the moon illuminates the rest of the canvass, which is comprised of the lake and mountains in the fore and background. This creates the vista that the five hunters take in, during their twilight moment of contemplation that the painting captures. The latter is a consistent theme that informs Ruger’s art collection.

Newell Convers Wyeth’s Two Hunters and Canoe

Newell Convers Wyeth’s Two Hunters and Canoe is a splendid painting that floods the canvass with golden color. A dazzling orange-yellow sunset, in what can only be interpreted as a moment of reflection by two hunters, dominates the canvass. The two men look out into a vivid sunset that illuminates the entire canvass, giving the work a strong sense of place and time.

Two Hunters and Canoe bespeaks of serenity. More importantly, the painting depicts the camaraderie between the two hunters, another prominent theme found in many of Ruger’s paintings.

Two Hunters and Canoe entices one’s imagination to join the two hunters; we appreciate the ability of representational art to capture and appropriate a moment in time of the lived experience.

The contour of the two hunters appears photographic, as if the rest of the canvass was painted around them. The two men are in agreement that the sunset they are witnessing is truly spectacular in its radiance. The soft glow of sunlight on their faces acts as a suspended animation of a moment in time that is recorded for posterity. Moreso, enlightening representational art, as is the case in Two Hunters and Canoe, can remove us momentarily from the sensual and fleeting by granting us a vision of the sublime and enable us to intuit transcendence.

Having been conditioned by the sterility and banality of abstract art and its many variants for what now seems an eternity, the aesthetic sensibility of people in postmodernity has all but been castrated.

The idea that the two hunters in the painting take time to experience the stillness and splendor of a radiant sunset will scandalize people who have been conditioned by the Internet and social media.

William Herbert Dunton, Sentinel of the Plains

The American painter, William Herbert Dunton (1878-1936), an easterner, was dazzled by the bright sun and vivid colors of New Mexico. After several trips to that state, Dunton moved to New Mexico, eventually becoming one of the originators of the Taos art movement.

Dunton was one of the founders of the Taos Society of Artists. Even though he was born in Maine, Dunton worked as a ranch hand, thus came to know the American West from firsthand experience.

As a young boy, Dunton became enamored with the outdoors. Going on fishing and hunting trips with his grandfather, young William often took a sketchbook with him.

Sentinel of the Plains may have originated as a painting to illustrate the cover of a novel. The idea of the cowboy as a rugged

individualist, who lived far away from urban centers, had gained traction by the time Dunton was a mature painter.

Because cowboys faced many of life’s contingencies alone and with full understanding that no one would come to their rescue, their image as genuine pioneers began to take on heroic proportions.

Sentinel of the Plains has a solitary cowboy sitting on his horse, on a rocky outcrop, overlooking a vast rocky terrain. He is reflective, taking a moment to contemplate his route through the mountains.

The painting is loyal in its realism: the landscape, color, sheen and musculature of the horse, the cowboy leaning back on his saddle in a posture that depicts confidence and self-reliance. The boulders and rocks on the ground and sparse desert vegetation reflect bright light, while clouds cast a large shadow over the lower right quadrant of the painting.

Unlike Dunton’s Return of the Grizzly Hunters, another of the painting’s that appear in After the Hunt, the light in Sentinel of the Plains is luminous but soft. This is a sharp contrast to Return of the Grizzly Hunters, where the land is covered in snow and darkness has descended on the hunters who, presumably, return to camp at dusk. Dunton’s use of blue pigment dominates Return of the Grizzly Hunters. Working its way from the background through the middle and foreground of the painting, the intense dark blue color gradually turns into lighter shades of blue. This work offers hints of tonalism.

Cloud World

Cloud World is considered to be Maynard Dixon’s most iconic painting. It is likely his most recognized work. Cloud World was recently loaned to the Tucson Museum of Art for a Dixon exhibit that included over 200 paintings.

Cloud World is a unique aesthetic take on the Western landscape; Dixon’s formal expression is reminiscent of Art Deco. Art Deco and the American Southwest desert? Modernism, perhaps? Dixon explains: Artist “must beware of schools, cults, dogmas, isms, must learn from all and give obedience to none.”1

Cloud World is a difficult work to classify. One reason for this is the easily recognizable subject matter of the painting. Dixon loved the American Southwest, the seemingly endless expanse of land, sky, and clouds that, casting shadows, constantly change the color of the terrain.

Looking across the vast expanse of desert to a mesa that takes up almost the entire bottom of the painting, the blue sky and quasi-cubist rendition of clouds make up a large portion of the canvass. The formation of the clouds, in what Dixon refers to as “space division,” delivers the eye the linear base of the clouds. Dixon’s aesthetic imagination pays allegiance to the flat base of cumulus clouds.

While Dixon does overlap clouds in order to show perspective in distance, his use of linear spacing creates the illusion of altitude and distance. The illusion of linearity is achieved by enabling pockets of blue sky to frame the base of the clouds. Pockets of blue sky that pop out between clouds delineate the clouds from each other.

One significant aspect of Cloud World that grounds the painting in the American Southwest is the inclusion of two minuscule, almost unnoticeable figures on horseback. Without them, the painting can be interpreted as a Daliesque dreamscape that borders on the surreal.

1 Adrienne Ruger Conzelman, After the Hunt: The Art Collection of William B. Ruger. (Stackpole Books: Mechanicsburg, PA., 2002), 114.

________________________

Pedro Blas González is Professor of Philosophy at Barry University, Miami Shores, Florida. He earned his doctoral degree in Philosophy at DePaul University in 1995. Dr. González has published extensively on leading Spanish philosophers, such as Ortega y Gasset and Unamuno. His books have included Unamuno: A Lyrical Essay, Ortega’s ‘Revolt of the Masses’ and the Triumph of the New Man, Fragments: Essays in Subjectivity, Individuality and Autonomy and Human Existence as Radical Reality: Ortega’s Philosophy of Subjectivity. He also published a translation and introduction of José Ortega y Gasset’s last work to appear in English, “Medio siglo de Filosofia” (1951) in Philosophy Today Vol. 42 Issue 2 (Summer 1998).

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link