by Hugh Fitzgerald

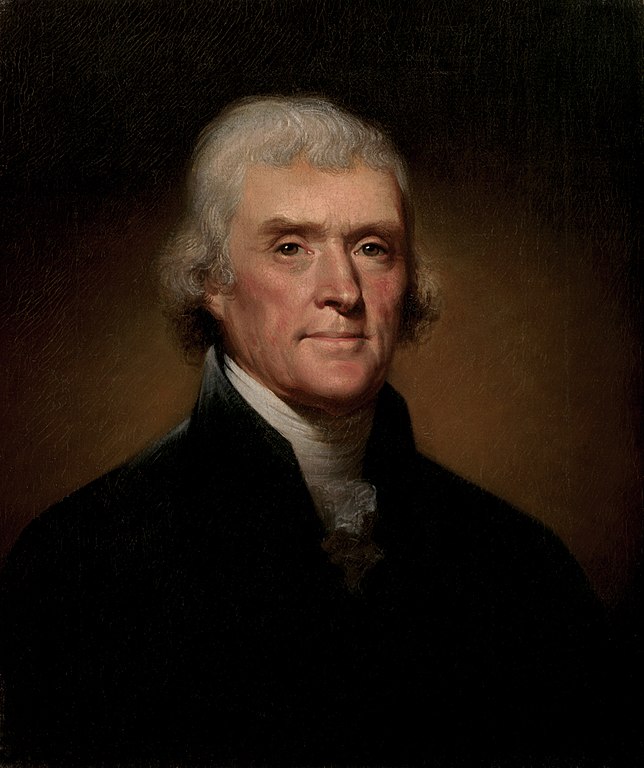

“America’s First Ramadan Break-Fast Was Hosted by Thomas Jefferson,” says Atlas Obscura, a site that says “our mission is to inspire wonder and curiosity about the incredible world we all share.” The article yesterday by Natasha Frost attempts to suggest that the “tradition” of the Iftar Dinner goes all the way back to Thomas Jefferson who, as is well known, was asked by a visiting Muslim envoy of the Bey of Tunis, one Sidi Soliman Mellimelli, to postpone the dinner to which Jefferson had invited him, along with others, until after sundown, which Jefferson, as a matter of courtesy, did.

Frost states:

Observing this holy month and its daily fasts in such a foreign environment must have been a challenge. Newspaper commentators at the time thought of him contemptuously, variously “depicting him as a sex-crazed barbarian, or associating Islam with licentiousness,” writes Jason Zeledon. But in Thomas Jefferson, he had an unexpected ally. Despite facing criticism for his hospitality from Federalists in Connecticut and Vermont, Jefferson looked after his Muslim visitor graciously, going so far as to rearrange a dinner party around Mellimelli’s fast. In doing so, America’s third president became the country’s first ever host of an iftar meal.

What actually happened is clear for those without an insensate need to make Islam, as Barack Obama repeatedly claimed it was, “always part of America’s story.” Jefferson was not putting on an Iftar dinner. A little history will help: Mellimelli came to Washington as the envoy of the Bey of Tunis. The Americans had blockaded the port of Tunis in order to force the Bey to halt his attacks on American shipping. Mellimelli was sent to make an agreement that would end the blockade. Invited by Jefferson to a dinner at the White House set for 3:30 (dinners were earlier in those pre-Edison days of our existence), he requested that it be held after sundown, in accordance with his Muslim practice, and Jefferson, a courteous man, obliged him. There is no hint that the dinner had changed in any way; no one then called it, or thought of it, as an “Iftar dinner.” Mellimelli himself did not describe it as an “Iftar dinner.” There is no record of it being anything other than the exact same dinner, the same menu, with wine (no removal of alcohol, as would have been necessary had it been a real Iftar dinner), the only change being that of the three-hour delay until sunset.

Frost continues:

It was, by no stretch, a traditional iftar, nor what Mellimelli would have been used to, without sweet dates to start the meal or the Tunisian dishes he was familiar with. But this gesture of hospitality must have seemed an outstretched hand at what was perhaps a very lonely time—a recognition that Jefferson and his peers respected and valued Mellimelli’s religious practice, and would do whatever they could to accommodate him, and it.

Yet nothing Jefferson said or did at the time, or in his later writings, indicates that he thought of that delayed dinner as an “Iftar dinner”; nor did he think he was in any way honoring or accommodating the practice of Islam.

In fact, Jefferson had a very dim view of Islam, which came out of his experience in dealing with the Barbary Pirates, that is, the North African Muslims (in Morocco, Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli), who attacked Christian shipping and seized ships and Christian sailors and then demanded ransom. The sums were not trivial; the American Republic found itself spending 20% of its national budget on such payments. These continued until Jefferson became President, stopped the practice of paying such tribute, and instead made war on the Barbary Pirates. And that worked.

In 1786, years before he became president, Jefferson, along with John Adams, met with the Tripolitanian envoy Sidi Haji Abdrahaman in London. Perhaps by then Jefferson had read the Qur’an he had purchased in 1765 out of curiosity (no one knows how much of that Qur’an Jefferson may have read, or when, though some Muslim apologists have baselessly claimed he must have bought his Qur’an out of sympathetic interest in Islam). If he did read it, it would have helped him to understand the motivations of the North African Muslims. Certainly by the time he became President in 1801, he was determined not to negotiate with the Barbary Pirates, but to implacably oppose with force these Muslims whom, he knew from his encounter with Abdrahaman in London, were permanently hostile to all non-Muslims.

In London, Jefferson and Adams had queried the Tripolitanian ambassador “concerning the ground of the pretensions to make war upon nations who had done them no injury,” for the Americans had done nothing to deserve being attacked, and the ambassador replied, as Jefferson reported:

“It was written in their Koran, that all nations which had not acknowledged the Prophet were sinners, whom it was the right and duty of the faithful to plunder and enslave; and that every mussulman who was slain in this warfare was sure to go to paradise.”

And later, Jefferson reported to Secretary of State John Jay and to Congress at greater length, with a nearly identical quote from the ambassador:

“The ambassador answered us that [the right] was founded on the Laws of the Prophet, that it was written in their Koran, that all nations who should not have answered their authority were sinners, that it was their right and duty to make war upon them wherever they could be found, and to make slaves of all they could take as prisoners, and that every Mussulman who should be slain in battle was sure to go to Paradise.”

These reports do not sound as if they came from someone who thought well of Islam. The more dealings Jefferson had with the representatives of the Barbary states, and the more he learned from them directly of the tenets of the faith, the more he began to understand the aggressive nature of Islam, the centrality of Jihad, the inculcation of permanent hostility toward non-Muslims, and the heavenly reward for Jihadis slain in battle.

The Iftar dinner “tradition” begins not with Jefferson in 1805, and that three-hour delay in a meal that was otherwise unchanged, but with our latter-day interfaith outreach presidents — Clinton, Bush, Obama — each of whom, in his own way, has managed to ignore or misinterpret the texts and teachings of Islam.

That “tradition” of Iftar dinners in the White House is less than 20 years old, as compared with the other “tradition,” ten times as long, that is, the 200 years of Iftar-less presidencies. That short-lived “tradition” has been ended, for now, by an administration that continues to exhibit a better sense of what Islam, foreign and domestic, is all about, than its predecessors. The interfaith outreach farce that the Iftar Dinner at the White house embodies, honoring Islam — while, all over the world, every day brings fresh news of Muslim atrocities against non-Muslims, more than 33,000 such attacks since 9/11/2001 alone, not to mention attacks as well against other Muslims deemed either of the wrong sect, or insufficient in the fervor of their faith — has now come to an end, if only for four years. That is certainly what Jefferson (and John Adams, and that most profound presidential student of Islam, John Quincy Adams), if not Atlas Oscura, would have wanted.

And since John Quincy Adams has been mentioned, why doesn’t Atlas Obscura take it upon itself to share with its readers what that most scholarly of our presidents wrote about Islam? It does not date. And it might prove most instructive.

First published in Jihad Watch.

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link