by Michael Curtis

In the midst of protests and violence in the streets stemming from BLM issues in the U.S. it is befitting to welcome this week the centennial birthday of an archetypical character, the influential black alto saxophone musician, Charlie Parker, born on August 29, 1920 in Kansas City, who died on March 12, 1955 in New York. A troubled man, a user of heroin, an addiction that first developed as a result of a car crash that led him to take morphine, who then became an alcoholic, leading to erratic behavior, he died at age 34 of lobar pneumonia, bleeding ulcer and long- term substance abuse. The doctor examining him thought he was 20 year older than he was. Parker died in the suite of the Baroness Pannonica de Koenigwerter, Kathleen Rothschild. Usually known as “Nica.” the Baroness was so affected by the ballad Round Midnight, that she left her diplomat husband and five children in France to become the patron of New York jazz musicians, of whom the best known is Thelonious Monk.

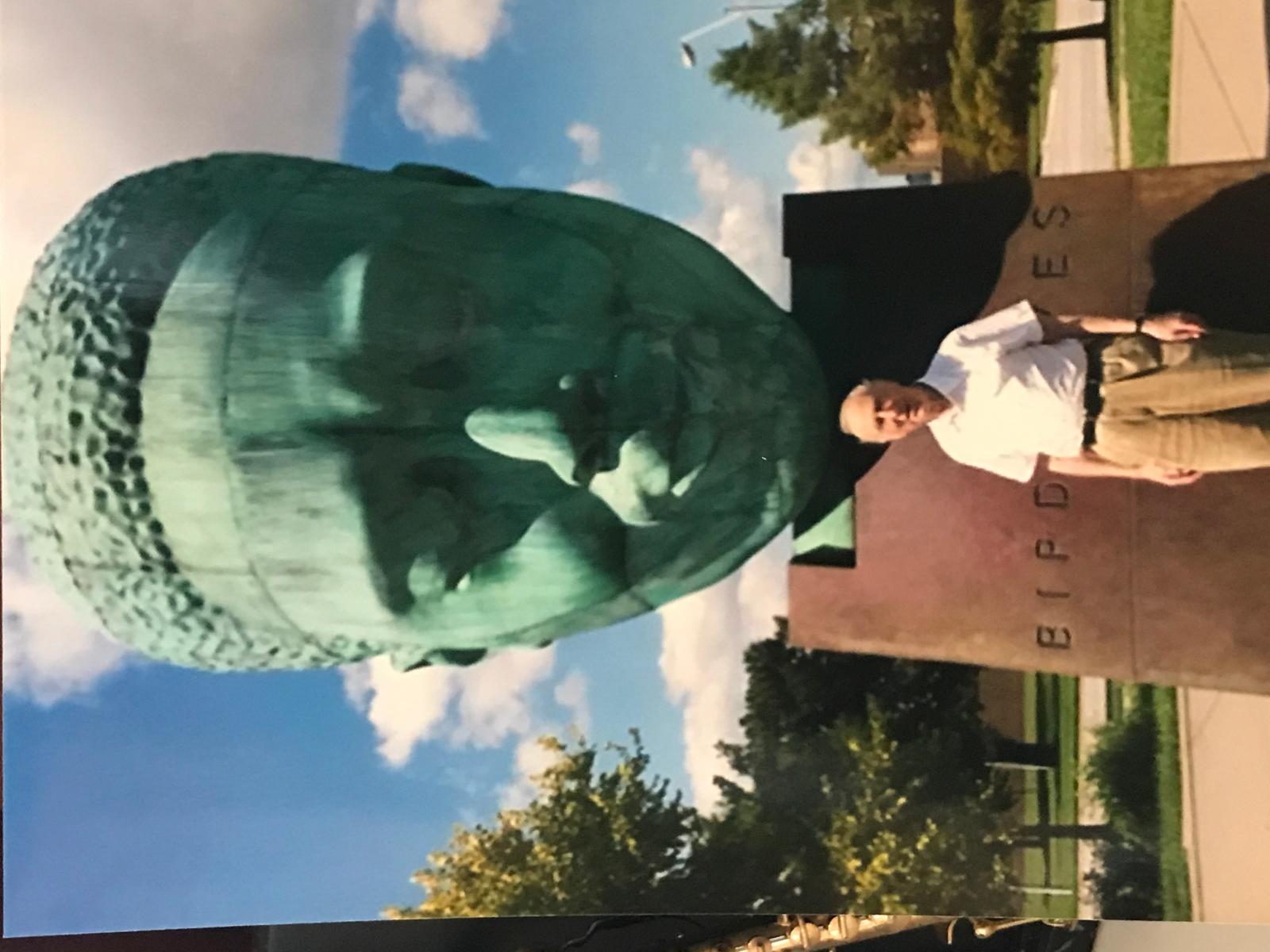

Yet for all the turbulence in his life and career, Parker with his distinctive musical style was a revolutionary pioneer with fresh ideas and virtuosity who changed the course of music, creating a bridge between the swing big band era and the later cool, modern jazz. He was honored by having a music club in New York, Birdland, named after him; he was the subject of paintings by Jean-Michel Basquiat, and of a film Bird directed by Clint Eastwood.

In the film La La Land the jazz pianist hero comments on jazz, “It’s conflict and it’s compromises. It’s new every time, and it’s dying.” The life of Charlie Parker illustrates the statement in two ways. One is the nature and extent of black participation in America’s contribution to music; the other, more generally, is the vitality, the diversity, and the ever-changing nature of jazz.

Jazz is an American musical form, recognizing and using the musical past but always adding a new vocabulary. Jazz originated in African-American communities and in brothels in New Orleans in the early 20th century. Its history is one of an art form of different styles, a wide range of music, from early brass band marches through ragtime, blues to swing, to bebop, cool, modal jazz, abandoning chord progressions to use scales as the basis of musical structure, free jazz, jazz-rock fusion, and Afro-Cuban. It is made distinctive by spontaneity, improvisation, changing of melodic lines, harmonics and time signatures. It can be viewed as a mixture of classical music with African and slave songs from West African culture and musical expression.

For a long time, the question has arisen of whether jazz is black music, implicitly suggesting or alluding to a cultural civil war among ethnic groups. Certainly, its roots are black, but did this mean that whites appropriated the sound and style of black musicians? As a minimum, one can agree that white musicians played jazz and were admired but they didn’t fundamentally change the course of jazz as blacks did. Some of those changes can be illustrated, starting with Scott Joplin with his Maple Leaf Rag, W.C. Handy and St. Louis Blues, Louis Armstrong in the red-light district of Storyville in New Orleans, through Kansas City with Count Basie and Lester Young, Duke Ellington, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, and John Coltrane.

But the contribution of white musicians cannot be ignored, from the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, Bix Beiderbecke, Frank Trumbauer and his C melody sax, Jack Teagarden, Chicago style Jazz, Eddie Condon and Bud Freeman, the big bands of the swing era , Benny Goodman, Glenn Miller, and Artie Shaw, Bill Evans, Stan Getz, and cool jazz. In fact, Lester Young said that Frank Trumbauer was his idol; “I tried to get the sound of the C melody sax on the tenor. That’s why I don’t sound like other people.” Louis Armstrong said he admired Beiderbecke. Remarkedly, the song, Livery Stable Blues, recorded by the white group, the Original Dixieland Jass (sic) band in February 1917 was the first jazz recording.

The reasonable thing is to say that jazz, deeply intertwined with concepts of race in the U.S., stretched across the racial divide, as well as being an outlet for black musicians, for whom it also provided upward mobility even if social discrimination affected their lives. It encouraged contacts and a certain integration between whites and blacks, with blacks often regarded as more musically advanced. Disregarding any fantasy of “systemic racism,” jazz led to major breakthroughs in racial integration among the players as with Benny Goodman who hired and played with Teddy Wilson, Lionel Hampton, and Charlie Christian.

One of the styles in the ever changing jazz world was bebop or bop in the 1940s, a genre extremely different and indeed opposite from the swing music of the big dance bands. Its music was meant to be listened to seriously, not as a background for dancing. It was different with its new vocabulary of passing chords, substitute chords, altered chords, flattened fifths, tritones, musical intervals composed of three adjacent whole tones, and adding extra notes to chord changes. Again, some have argued bop was a deliberate expression of a black subculture, to differentiate it from white culture, but two factors are relevant. One is the fact there is no evidence that bop performers, primarily black, were not expressing any form of black nationalism or reverse racism; the other is that whites, such as Stan Levey, Shelly Manne, Al Haig, Joe Albany, and Red Rodney, were almost immediately involved in the style.

The main founder of bop was Charlie Parker, who was nicknamed Yardbird or Bird, possibly to indicate he was as free as a bird, or because in an accident his vehicle killed a chicken, or simply because he was a voracious eater of chicken. Bird was outstanding for his extraordinary alto sax playing with his fast tempos, advanced harmonies, rapid passing chords, chord substitutions. Born of working-class parents, one black, one Choctaw, Parker came out of Kansas City, a significant and relevantly affluent black metropolis though dominated by political boss Tom Pendergast. He started played in KC night clubs soaked in the blues and with Jay McShann, the last important KC swing band, and then left to join the black musicians in the Savoy Ballroom in Harlem in New York, playing with Earl Hines and Billy Eckstine bands, and becoming linked in 1940 to Dizzy Gillespie, his co -founder of bop, and to pianist Bud Powell and drummer Max Roach.

Parker confessed he practiced 15 hours a day, sometimes in a park, for a number of years to master his instrument, the alto sax, and adopt his rapid, angular melodic lines. To practice, he memorized Lester Young’s solos in the Count Basie recordings. Parker was a brilliant improviser; his solos were spontaneous but full of new melodic ideas. His playing tried to exemplify his maxim that “I thought that music should be clean, very precise.” He hit on a finding, that 12 semitones on the chromatic scale can lead methodically to any key.

Bird was interested in classical music, particularly in Igor Stravinsky, and delighted in being accompanied by strings. He exemplified the reality that jazz, developed by blacks, was influenced by European harmonic structure as well as by African rhythmic intricacy. In his playing Bird used devices such as triplets and pickup notes that precede the dominant in a bar to lead into choral tones, and used passing tones, melodic embellishments that occur between two stable tones.

Some of Bird’s compositions, such as Confirmation, with rapid chord changes, an extended cycle of fifths, and intricate harmonic rhythm, are original constructions However, many of his compositions are examples of the contrafact, a composition of melody overlaid on a familiar harmonic structure or use of borrowed chord progressions. These compositions with long complex melodic lines are borrowed from familiar standards of the Great American Songbook or from the 12 bar blues pattern. Some compositions are based on George Gershwin’s “I got rhythm,” such as Anthropology, Moose the Mooche, and Chasin’ the Bird. Others are Bird of Paradise, based on Jerome Kern’s “All the things you are,” or Dewey Square based on Gershwin’s “Lady be Good,” or Ornithology based on “How high the moon.”

Charlie Parker was a complex figure, a genius who made a great contribution to jazz, extending it and moving it out of the dance floor. He was the master of melodies without vibrato or tonal coloration, of advanced harmonics and polyrhythms. The best way to celebrate Bird is to listen to his recordings, to their beauty and power. In addition, one of Parker’s aphorisms is appropriate in the present day political divisions in the U.S., “Study is absolutely necessary in all its forms.”

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link