The Great Gatsby

by James Como

Once a contrarian, always . . . Later on, though, with nothing much to do but to be contrary, vexations mount up, ‘de-contextualized’, as they say, so that mostly vexations. These may have to do with appetites, but in my case they are intellectual. For example, the consensus (always, always dangerous) about The Great Gatsby.

Sure, there is window dressing that points to amorous loss, and the realization that material goods do not make for enduring happiness, or that one’s origin is one’s destiny (inviting pretense and, eventually, exposure, if only to one’s self). These make for an insightful and deeply-felt character study, but they do not make for character.

These losses are not – consensus to the contrary notwithstanding – what Gatsby, or Gatsby, is about. They – their worthlessness, or transience, or unreliability – are not really the morbidities that Fitzgerald, in the midst of a fittingly exuberant age (at some age any age can seem exuberant) would display.

No. These are elements in what C. S. Lewis has called “the dialectic of desire,” a tracing (or, as the CIA puts it, a “chasing back the cat”) of objects of desire – sex, fame, creature comfort – until one realizes that, in fact, these were not the real objects of desire at all, that the sehnsucht, the longing, persists no matter the winning of love, money, fame, self-improvement or social ascent.

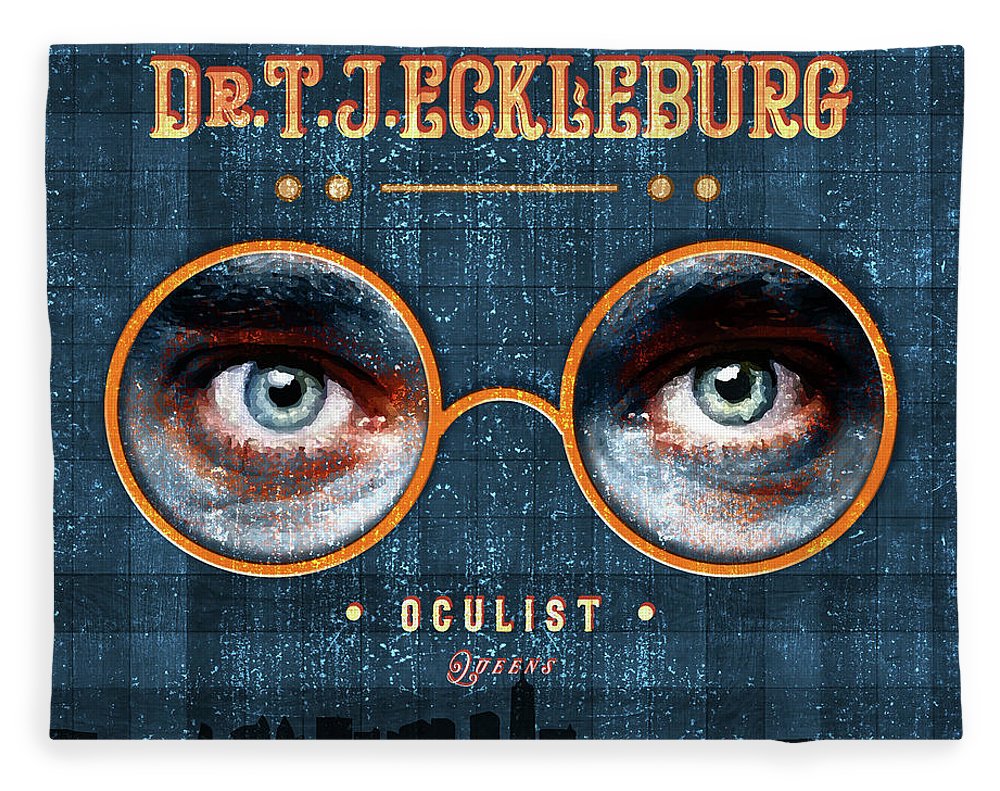

Why is that? Lewis has wondered. Because, he concludes, the object of our deepest desire is not of this world; nor was Gatsby’s. Those large billboard eyes are watching, disinterestedly, to see if Gatsby will make it or not, that is, will discover in himself our genuine object of desire.

Of course, he does not. He is murdered, his dialectic aborted, and Fitzgerald leaves his reader believing that his book is about the perils of one’s reach exceeding one’s grasp. Now, there is nothing false and much useful in knowing of such perils, of their varying manifestations: psycho-social diagnostics, especially when so elegantly and movingly arrayed, are compelling.

But they are incomplete. At the end of the day, Fitzgerald had more in his soul than he realized, and so stopped just short. He seems to have believed that psycho-social dysfunction is an affliction whereas it is actually a symptom of despair. We gaze at that green light at the end of the dock as road sign pointing to our home: “For Thou hast made us for Thyself and our hearts are restless till they rest in Thee,” the genuine object of our desire. That’s what The Great Gatsby is about.

Not only the reader but sometimes the writer, too, is the last to know.

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link