by Theodore Dalrymple (February 2018)

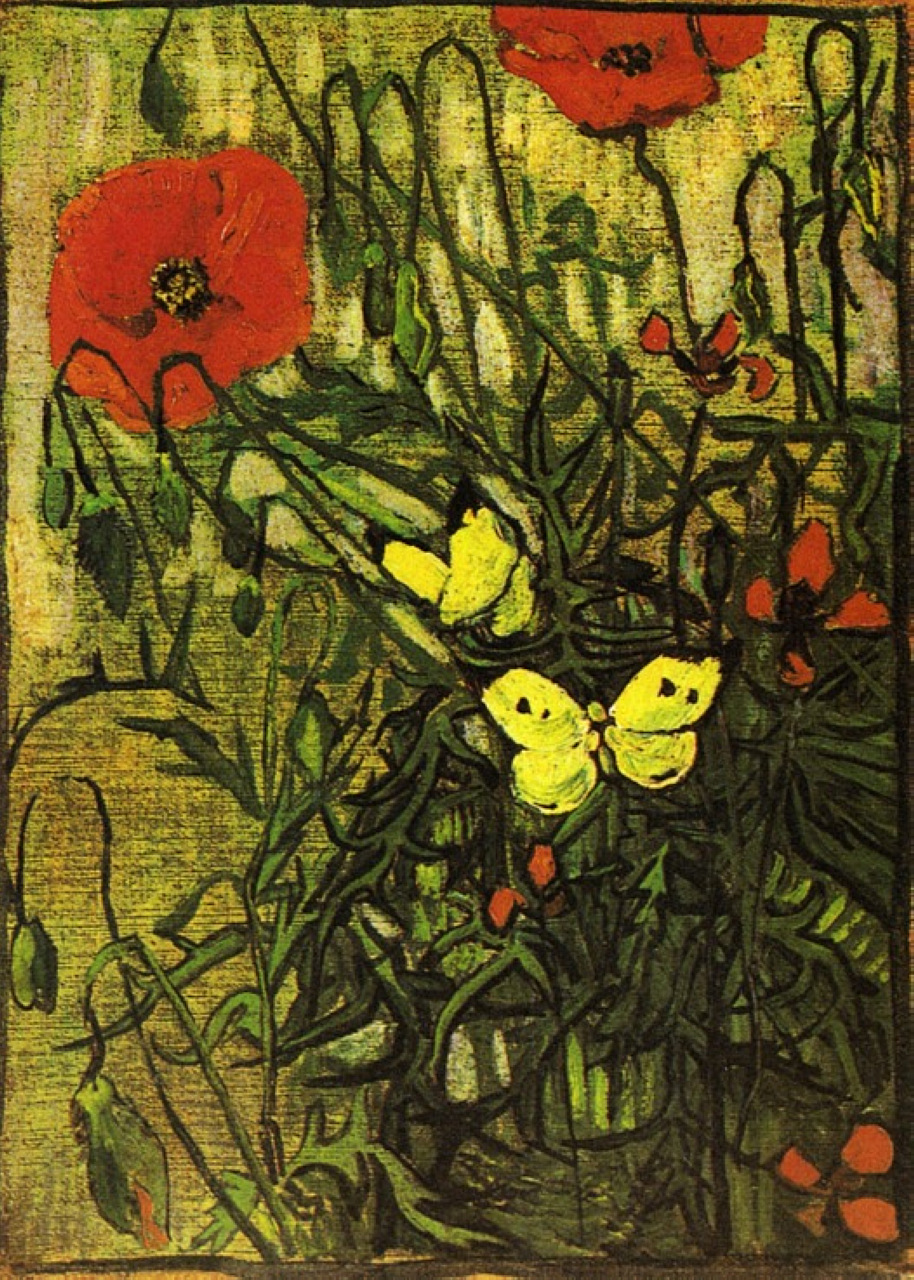

Poppies and Butterflies, Vincent Van Gogh, 1890

.jpg) ur lives are so impregnated with meaning, thought, intention, moral judgment and feeling, that we project them on to all animate nature. No matter how much we tell ourselves that we ought not to do so, that it is an intellectual error or mere sentimentality to do so, we do it all the same, we cannot help ourselves.

ur lives are so impregnated with meaning, thought, intention, moral judgment and feeling, that we project them on to all animate nature. No matter how much we tell ourselves that we ought not to do so, that it is an intellectual error or mere sentimentality to do so, we do it all the same, we cannot help ourselves.

No dog-owner can believe, as Descartes would have had us believe, that his beloved animal is just a more flexible and complex food-mixer, a food-mixer with more built-in programmes, maltreatment of which would be of no particular moral interest or significance. As flies to wanton boys are we to the gods, said Gloucester in King Lear: but note that the boys who pick the legs and wings off these unattractive insects are wanton, which is not a term of approbation. In this context, it means heedlessly or thoughtlessly cruel; and anyone who thought that this was not meant as a critical comment on the boys could hardly be said to understand our language. Theirs—the boys’—cruelty is not cruelty to be kind, but cruelty to be cruel; but, of course, you can be cruel only to the sentient. If one kicks a food-mixer, say because it does not work as well as expected, we might be called foolish, but hardly cruel.

Gloucester did not say As stones to wanton boys, as he might have done without ruining the rhythm of his language: for after all, wanton boys might throw stones at windows. But their wantonness would not then be cruelty to glass, it would be the heedless way in which they caused problems to others, and enjoyed doing so. The fun is in the pain caused.

But even those of us who are appalled at Descartes’ opinion of dogs as automata do not think that flies are capable of suffering very much, even if they do try to escape their tormentors if they have the opportunity. Our condemnation of the wanton boys is only to a very slight extent on the flies’ behalf: after all, few of us actually like flies, or do everything in our power to protect or preserve them. No one says, ‘He is a good butcher because he has many flies in his shop.’ If a fly could speak and told us that it had landed on our plate because, after all, it has to eat something, we should reply like Louis XIV, ‘I don’t see the necessity.’ Fly sprays do not cause us any moral qualms (apart from the destruction of the ozone layer, entry into the food chain, etc.) even if they cause agony to the flies, as does poisoning by strychnine to humans.

We are not just hypocrites, however. We decry the wanton boys because their intention is not to rid the world, or even their small corner of the world, of disease-spreading flies, it is to be cruel for its own sake. We apprehend that those who torture flies will, or rather may, one day torture the higher animals (if one is still permitted to speak of higher and lower in an evolutionary sense), just as Heine said that where books are burnt they will eventually burn people. This, of course, is a statistical regularity, not an invariable rule: not every wanton boy becomes a torturer, and probably the majority do not, in the same way that the majority of drunken drivers arrive home safely. But a high proportion of torturers (using the term loosely) started out on flies and birds and cats. No one, surely, thinks the better of a boy for having picked the legs and wings off flies. As for the gods, they really should know better.

Even if we know it to be absurd, we still ascribe moral qualities even to insects, which of course depend to a large extent on their aesthetic qualities. Bees are good and wasps are bad, a difference that is not wholly accounted for by the fact that bees accomplish humanly important ends, whereas wasps—as far as I know—do not. Bees are the teddy bears of the insect world whereas wasps are the snakes; one is furry and cuddly (notwithstanding its capacity to sting) and the other shiny and cold. Where the bee sucks, there suck I: no one would say where the wasp nests, there nest I.

Who does not love butterflies? Such peaceful, gay (in the old sense) creatures! I have met people who do not like dogs—whole religions have a dog-in-the-manger attitude to them, so to speak, regarding them as ritually unclean—but I have never met anyone who does not romanticise butterflies. They are harmless, they are like flowers that float on the wind. The fact that their numbers seem ever-declining bring no joy to anyone; in fact, we are all pained by it. ‘Even the butterflies are free,’ protested Harold Skimpole in Bleak House, to which we are inclined to respond, ‘Especially the butterflies are free.

Yes, what a wonderful life they have! In my garden in France, for example, they do nothing but flit from lavender flower to lavender flower all day, with no responsibilities at all. The swallowtails in particular seem to dance delightfully on unseen currents of air, and often chase each other playfully, with affection rather than aggression. They are children of the sun.

One disregards the dark side of their existence. There are birds (I imagine) that eat them, and for these they must perpetually be on the lookout, as for muggers in the slums. When the sun goes down, they disappear, presumably to their rest (do butterflies sleep?), during which they must be vulnerable indeed. Where do they go at night? No doubt lepidopterists know the answer, which they found at an expense of ingenuity and doggedness quite beyond most of us, who are content to know only what others have laboured to find, taking the knowledge for granted and assuming that, like the Kim dynasty in North Korea, it was always there and required no originator or discoverer.

Even for us, however, there is a dark side to butterflies, namely caterpillars. There are no butterflies without caterpillars, and recently my wife was upset to discover that some bushes that she had planted were killed almost overnight by the depredations of these larvae. They ate every leaf as if there were no tomorrow, which there wasn’t for these bushes, which were left mere stalks in the ground.

Caterpillars have never had a good reputation, necessary as they may be if there are to be butterflies to delight us on a summer’s day. Are not the corrupt courtiers of Richard II called the caterpillars of the commonwealth in Shakespeare’s play? There are types of caterpillar that devastate crops as comprehensively as a plague of locusts. I have myself seen in East Africa the so-called army worm, a huge column of caterpillars hundreds of yards long and twenty yards wide, marching (if caterpillars can be said to march) in perfectly disciplined fashion in search of new fields to devastate. Presumably they fanned out a little when they reached a suitable crop, otherwise only the front of the column would eat its fill; but for those who liked fascist rallies or military parades, it was a most impressive display. For me, it was an interesting biological phenomenon, one that occurred at intervals; for the local farmers, already on the margins of subsistence, it was a cause of despair.

Perhaps there is a lesson, or even more than one lesson, in our contradictory view of butterflies and caterpillars. The first is that with which I started: that we imbue animate nature with moral qualities. My wife, on discovering the depredations of the caterpillars overnight, was not only sad for the bushes (and her wasted labour) but morally outraged at the conduct of the caterpillars. Could they not have gone elsewhere? Had they been waiting to pounce on her bushes as a revenge on Man for having so reduced the habitat of their biological relatives in the world? Or did the bushes in some sense call them into being, their presence allowing them to become numerous enough to destroy them? No rational reflection, however, could entirely expunge the idea that they were malicious, that they were full of spite and resentment, like voters during an election campaign. Man prides himself on his intelligence, but insects on their power to destroy.

Our very different response to butterflies and caterpillars should remind us of the Buddhist lesson that there is no pleasure without pain, but also that we often disregard the necessary conditions of our own delight. Many are the people, for example, who delight in the artistic products of societies that they would be the first to denounce as unjust or reprehensible, though the great artistic achievements of those societies were possible only because of the injustice of them. Doctor Johnson said that all great achievement was the result of leisure, but it offends our contemporary sensibility that there should be many who labour that some should be at leisure, especially as most of those who are at leisure produce nothing themselves. When Thorstein Veblen identified the Leisure Class, he did not do so imagining that his description would attract widespread approbation of, or affection for, that class. And perhaps the resentment of that class is not entirely unjustified: for we have somehow succeeded in producing a leisured class that indeed has neither produced nor called forth works of transcendent value for future generations. A leisure class (whether by heredity or individual effort) may be a necessary condition for Johnson’s great achievement, but it is certainly not a sufficient one.

Behind every great fortune, said Balzac, lies a great crime. Whether or not this is true (it would be interesting to investigate it empirically, though those who believed it to be true would no doubt preserve their faith by claiming that those cases in which no great crime had been found had been insufficiently researched), one might say that behind every great man-made work of beauty their lies some ugliness. I have friends who look back on the ages on which the greatest works of Man—at least, the greatest artistic works of Man—were created as if they must have been great or wonderful in all other respects: though in fact, they would have been horrified by the dirt, the misery, the smells, the diseases, the vermin of those ages, and would at once have sought asylum in our hygienic and deodorised world without artistic grandeur. For modern man, comfort is the highest good, and perhaps it always would have been had it been a possibility. After all, modern man emerged gradually from his ancestors, not like an imago from a chrysalis. He underwent no metamorphosis.

When we take delight in butterflies, then, we have to disregard the conditions of their production, or else our delight would be vitiated. This is the sense of Wordsworth’s line that they murder to dissect. It is true that some dissectors claim that their dissections increase rather than detract from their aesthetic appreciation: who, after all, cannot but wonder at the marvellous contrivances of nature, irrespective of whether or not there was a contriver? Did not Darwin himself conclude his great work by saying that there was a grandeur in this (that is to say, his) conception of the living world?

Nevertheless, I suspect that those who take this view are not being quite true to their own psychology: that when they experience the beauty of butterflies, they do so in exactly the same way as everyone else, and that they dissociate their thoughts of butterflies from their thoughts of caterpillars: a willing suspension of knowledge, if you like. If they investigate caterpillars, it is for the sake of butterflies, not the other way around. As far as I am aware, no lepidopterist ever came to lepidoptery via caterpillars, and still, after a lifetime of study, it is the brilliant flash of the wings, the evanescent glimpse of heavenly beauty, that captivates them.

_____________________________

Theodore Dalrymple’s latest book is The Proper Procedure from New English Review Press.

Please help support New English Review.

More by Theodore Dalrymple here.

Theodore Dalymple is also a regular contributor to our blog, The Iconoclast. Please click here.

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link