by Marc Epstein (August 2019)

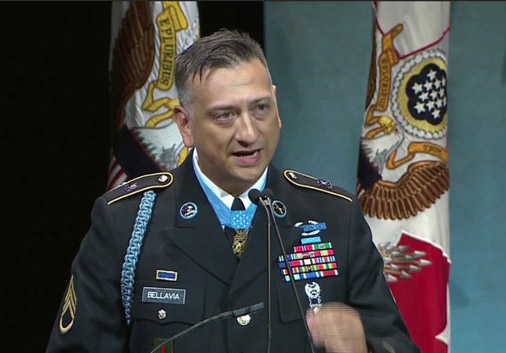

Hall of Heroes Speech, David Bellavia

This past June 25th, David Bellavia was awarded the Medal of Honor in the East Room of the White House by President Trump. It was in recognition of Bellavia’s heroism in Operation Phantom Fury, more commonly known as the Second Battle of Fallujah, on November 10, 2004.

In his recounting of the event, Bellavia remarked that it was his 29th birthday, and in the course of that night he thought it would also mark the day of his death, more than once.

This was the second time American troops had to fight for this ground, now a largely deserted city, except for the suicidal jihadis that they confronted. It was once home to one of the great academies of Jewish learning. Back in the 3rd century Fallujah was known as Pumbedita, or Pumbedisa in Aramaic “mouth of the river.” In the academy of Pumbedita and another academy in the city of Sura, scholars studied and crafted Judaism’s most rigorous and intellectually challenging series of exegesis now known as the Babylonian Talmud.

Read more in New English Review:

• All’s Well and Some Discontent

• From Jaws to Gums

• Branding: Fascist, ‘Folks,’ and Stalinoids

On November 10, 2004, nobody was studying Talmud in Fallujah, and even the awareness that this killing zone had once flourished in this capacity had been long forgotten. Ironically in the course of Bellavia’s single-handed encounter with a cell of drug-juiced jihadis, in a darkened house that had been transformed into a bunker/killing zone, they would taunt him with the epithet—misapplied in his case—“Jew.”

The combined U.S. armed forces, along with British and Iraqi allies, were attempting to restore some semblance of civilization to a war-ravaged urban landscape that had been subsumed by Islamic nihilism. There, they confronted an amalgam of the most hardcore Islamic jihadis numbering, by some estimates, about 3,000. It would turn out to be the bloodiest battle of the war.

This was the second war on Iraqi soil in which United States had engaged over the course of a dozen years. The 1991 Gulf War was precipitated by Saddam Hussein’s invasion and occupation of Kuwait in 1990. It was fought by a grand coalition of 39 countries assembled by George H. W. Bush. In all, 670,000 troops from 28 countries would be deployed, with the U.S. contributing the lion’s share, 425,000.

The war would be over in 6 weeks. The allied coalition suffered approximately 290 deaths, with America bearing the brunt of the casualties. Iraq is estimated to have suffered 25-30,000 in troop losses and between 100-200,000 civilian deaths. There were 1,000 deaths reported in Kuwait.

President Bush likened Hussein to the worst of the worst. He said Americans “are held in direct contravention of international law. Many of them reportedly staked out as human shields near possible military targets, brutality that I don’t believe Adolf Hitler ever participated in anything of that nature.” Nevertheless, the truce agreement essentially restored the status quo ante and left Saddam Hussein’s regime in place as the massive allied forces withdrew from the region. It was an outcome that Adolph Hitler couldn’t have imagined in his wildest dreams.

But the status quo as understood by the United States was not perceived the same way in the Islamic arc that extends from the Arabian Peninsula to Pakistan. So while we were enjoying a post-Gulf War leave and a sabbatical from world affairs precipitated by the collapse of the Soviet Union, a coalition of sinister forces was at work planning to return the favor by visiting an unprecedented wave of destruction on American soil.

It would be left to George W. Bush, son of George H. W., to address this catastrophe, just seven months after entering office in the wake of a historically contested election. The re-introduction of American military force into that region was precipitated by 9-11. Within a month of the attacks on New York and Washington, American troops invaded Afghanistan with the stated purpose of dismantling Al Qaeda and finding Osama bin Laden.

Iraq would become part of America’s focus once again when George Bush turned his attention to Saddam Hussein and the issue of weapons of mass destruction.

A coalition was assembled, albeit smaller than the first gulf war. Debates were held at the UN. Eventually a resolution passed that demanded a resumption of weapon inspections. The U.S. Congress debated the issue too and passed the Iraq Resolution authorizing the use of force. After Iraq’s refusal to abide by the UN resolution a second invasion of Iraq was launched in March of 2003.

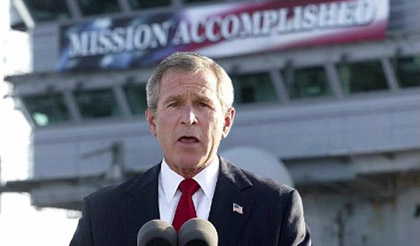

Once again, hostilities lasted about a month. But this time the regime was overthrown, Saddam Hussein was eventually captured in December of 2003, and America was left with a shattered state and an uneasy occupation. On May 1, 2003, President Bush announced the end of major combat in Iraq aboard the USS Abraham Lincoln. A “Mission Accomplished” banner in the background framed the scene.

Once again, hostilities lasted about a month. But this time the regime was overthrown, Saddam Hussein was eventually captured in December of 2003, and America was left with a shattered state and an uneasy occupation. On May 1, 2003, President Bush announced the end of major combat in Iraq aboard the USS Abraham Lincoln. A “Mission Accomplished” banner in the background framed the scene.

But when no significant caches of biological or chemical weapons were discovered, and a nasty insurgency erupted, the second Iraq war became a central issue in the 2004 Presidential election. The Bush administration’s honesty and motives were now openly questioned by the Democrats while Iraq devolved into something of a dystopian Islamist amusement park.

This was the Iraq that David Bellavia and his squad stepped into in Fallujah on the 10th of November, 2004.

Dave Bellavia & Me

According to his recollection, I first spoke with Dave Bellavia during a conference call in early November, 2012. I was asked to participate by a mutual friend who had established an organization designed to raise public and government awareness about the vulnerability and fragility of our electric grid. The participants were unknown to me at the time. I joined the group as a regular shortly thereafter.

Dave ran the organization out of the Buffalo area, right in the heart of the great Niagara power grid. I was told by my friend that he was a “great war hero,” but I paid no attention to it because my friend often described me as a “great historian and political analyst.” I thought that if Dave was a great war hero in the same way that I was a great historian/analyst, nothing further need be said.

Dave would run the weekly conference call. Each week I’d report on the latest defense-related developments regarding the EMP threat and foreign relations. A variety of experts would contribute to the conference call and Dave would report on the organization’s activities along the Niagara frontier. At some point we would talk to each other after the conference.

Despite the age gap, we discovered that we had a wide range of common interests and lots of shared attitudes. My academic training was in naval disarmament, so we often spoke about the Defense establishment. But we never touched on his personal wartime experience. We’d focus on the Bills, the Yankees, movies, theater, media, and the like. A phone friendship developed but my own medical issues prevented me from getting up to Buffalo and meeting him face to face.

When I’d regale him with anecdotes about the wide range of personalities who frequented my father’s business running the Luxor Baths and inhabited my childhood, he’d urge me to get it down on paper. Dave would say, “you don’t know this but you’re going to be a rich man one day.” I’m still not wealthy, but thanks to his encouragement, I put pen to paper and wrote an essay about it.

In the course of a conference call a few years later I heard someone else on the line mention that Dave had received the Silver Star. It was then that I decided that it was time to look him up. I read his Silver Star citation—his Medal of Honor citation is rather tame by comparison—did a double take, and then read it again. It seems my friend Henry’s description was accurate, at least when it came to Dave. I read about the veteran’s support organization he had founded and his primary run against Chris Collins. I streamed his radio show out of Buffalo when he asked me to come on as a guest.

Several guest appearances followed. Each time Dave would introduce me as “the smartest man I know,” and I’d have a good laugh for the day. We’d talk about current events, education, and America’s political miasma. While I was on the line, he’d send me texts like “the board is lighting up like crazy.” I had no idea if it was hyperbole, but it made feel good for a few minutes on those guest appearance days.

I ordered his book from Amazon, read through it rather quickly, and watched Michael Ware’s documentary about the war, Only The Dead, on NETFLIX. Ware, a Time/CNN reporter, was embedded in his squad, and trailed him into the ground floor of the house on November 10th. The footage in Only The Dead includes the run-up to the engagement and the aftermath. I viewed it several times and was struck by the ordinariness of the horror that was unfolding. It prompted me to reread the book—much more closely this time.

It dawned on me that the political polemics about our Iraq adventure aside, much of Dave Bellavia’s war passed over me and most of the American public like a stealth airplane in the night. To be sure, wounded warrior ads on TV, along with the obligatory 60 Minutes story about a veteran who either overcame or was destroyed by his horrific wounds, both physical and mental, became a fixture on the airwaves. The ritual closing of the evening news with a parent returning from deployment overseas and surprising his or her child in school has become de rigueur. I have to admit that the reality of Iraq was all pretty remote to me until a happenstance relationship readjusted my degree of separation.

I don’t think attending a Medal of Honor ceremony ever crossed my mind, but when Dave let me listen to the recording of the phone call from the White House, I told him I was going out to get a new suit. The President told him you can tell your family and friends, but the Pentagon walked that back and told him to keep it to himself. It turns out the logistics and planning for the ceremony is far more complicated than turning up at the White House on the day of the ceremony and pointing to your name on a guest list before you get scanned.

When Calvin Coolidge lived in the White House, any citizen could meet him and shake his hand on a Sunday, after church. Now, if you are going to be in the same room with President you have to go through extensive background checks just to get on the guest list. There was more to follow.

The invitees received a preliminary itinerary from Dave a few weeks before the ceremony with the caveat that it was subject to change. The bottom line was we were told that we would depart from one location and all attendees had to depart together. Transportation would be provided. We were also given a link that allowed us to make reservations at the hotel where a reception in Dave’s honor would be hosted by the Sargeant Major of the Army the night before. It would also be our departure and return destination.

I immediately booked a room. I wanted to get into the spirit of the moment so I booked a flight out of LaGuardia on Monday morning on the 24th of June. Navigating LaGuardia is my idea of doing something daring. I got lucky. My trip was seamless, and the hotel was just a short shuttle trip from the airport. The reception wasn’t until the evening so I made use of the gym, read, showered and dressed.

My first hint that the ambiance of the hotel was somewhat different from the other D.C. hostelries was when I entered the elevator to go to the reception. It was filled with soldiers, all female, in fatigues. When I got out at the 16th floor I encountered more generals than I had ever seen in my life—and that includes every war movie I had ever watched.

I met Dave Bellavia face to face for the first time too. We spoke, hugged briefly, and then I spent the rest of my time just taking it all in. I spoke with an armed forces media specialist about the whole undertaking and got a sense of the scope of what was to come. An Army band played contemporary music in the background. The host of the event, Sergeant Major of the U.S. Army Dailey, spoke briefly about Dave Bellavia and the forthcoming Medal of Honor ceremony the next day. Dave spoke briefly too and introduced his family. It was your basic army dress blue cocktail, hors d’oeuvres and pastry party-with lots of high-ranking brass, and members of Dave’s squad. It was a first for me. The atmosphere was pleasant and relaxed. It would set the tone for the next two days.

I met Dave Bellavia face to face for the first time too. We spoke, hugged briefly, and then I spent the rest of my time just taking it all in. I spoke with an armed forces media specialist about the whole undertaking and got a sense of the scope of what was to come. An Army band played contemporary music in the background. The host of the event, Sergeant Major of the U.S. Army Dailey, spoke briefly about Dave Bellavia and the forthcoming Medal of Honor ceremony the next day. Dave spoke briefly too and introduced his family. It was your basic army dress blue cocktail, hors d’oeuvres and pastry party-with lots of high-ranking brass, and members of Dave’s squad. It was a first for me. The atmosphere was pleasant and relaxed. It would set the tone for the next two days.

Medal of Honor Day

I’m an early riser and went down for a quick breakfast at the coffee bar. There was a hotel chef behind the counter who offered me a sampling of very fancy pastries. I introduced myself and he told me he was the hotel chef. When I told him I was here for the Medal of Honor ceremony, he told me the pastries were from last night’s reception.

He sat down with me while I ate my Total and he told me a bit about his job and the dignitaries who stay there. Sam Kaufman had worked in Buffalo too, so he had a bit of connection to the event. I told him that one of the army’s chief operation officers told me that the hotel had made a Medal of Honor confection sculpture that was in Dave’s suite along with an array of treats for his family. Sam told me he made it but didn’t have all his tools so he couldn’t get all the detail. He showed me a picture of it on his phone and sent it to me.

He sat down with me while I ate my Total and he told me a bit about his job and the dignitaries who stay there. Sam Kaufman had worked in Buffalo too, so he had a bit of connection to the event. I told him that one of the army’s chief operation officers told me that the hotel had made a Medal of Honor confection sculpture that was in Dave’s suite along with an array of treats for his family. Sam told me he made it but didn’t have all his tools so he couldn’t get all the detail. He showed me a picture of it on his phone and sent it to me.

I went back to my room and decided to get dressed and go down early just in case the schedule had been altered. When I put my new suit on I was surprised to find an American flag pin in my lapel courtesy of my salesman. I had told him I was going to the ceremony in the White House, and this was his contribution.

I never got to read more than a page of my Harry Bosch detective novel, always a good choice when you travel. A reporter for WBEN radio in Buffalo, the station where Dave works, was sitting next to me on the couch and asked me if I would allow him to interview me. He knew me from the show and now he could put a face to a voice. He wanted to know how I thought Dave would cope with the hoopla and the notoriety that goes along with it. I told him that since he had been a public figure in Buffalo so long and a professional in the communications business, I thought he could handle it.

.jpg) When the interview concluded I walked across the lobby and introduced myself to a friend of Dave’s and another Medal of Honor recipient. Gary Beikirch (standing at right) was a Green Beret medic, serving with the Montagnard tribesman when he was wounded and partially paralyzed during an attack. He continued to treat the wounded as he was carried to treat them, while he helped staunch the attack. He would receive two more serious wounds before he was evacuated.

When the interview concluded I walked across the lobby and introduced myself to a friend of Dave’s and another Medal of Honor recipient. Gary Beikirch (standing at right) was a Green Beret medic, serving with the Montagnard tribesman when he was wounded and partially paralyzed during an attack. He continued to treat the wounded as he was carried to treat them, while he helped staunch the attack. He would receive two more serious wounds before he was evacuated.

He was featured along with three other MOH recipients in a lengthy Wall Street Journal essay, ‘It’s a Lifelong Burden: The Mixed Blessing of the Medal of Honor,’ that appeared on Memorial Day weekend. I recognized him from his picture in the Journal.

When I said that my name is Marc Epstein and I’m a friend of Dave’s, Gary replied, “The radio Marc Epstein.?” I just burst out laughing. Gary lives in the Rochester area so he could listen to WBEN that broadcasts Dave’s show. We spoke about education and were in agreement that there’s big trouble in River City. Gary was a guidance counselor for 33 years and I was a high school Dean.

To the White House

The number of attendees continued to gather in the lobby, and we were instructed to form a queue and have our photo ID ready. It had to be either a driver’s license or government ID.

We were screened by the Secret Service. When the three buses were loaded up we proceeded with a full police car and motorcycle escort. It was a first for me, and I must admit I was impressed. We watched tourists snapping pictures on their phones as police and buses with opaque windows sped through the streets of the capitol. In the digital age when you don’t have to worry about wasting film it makes no difference. I wondered if they ever figured out who we were and where we were going. Us passengers found it amusing.

When we disembarked on the east side of the White House, we found that the Secret Service had set up an indirect path to the entrance to facilitate another series of security checks. We would be stopped, checked, and scanned three more times. I told the agent that I was a walking Home Depot aisle with lots of metal in my body. He was just concerned with explosives at his station, but he told me to tell them at my next stop. At my final stop I informed them, and when the agent wanded me, the wand went off like a Geiger counter. He laughed and said “You are a good walking ad.”

It was a hot day. Once inside we were greeted by a string quartet and glasses of water with lime. There were other quartets playing as I wandered through the rooms. We had access to the East Wing’s historic treasures. I took pictures and soaked it all in. There were military aides in all of them to answer any questions we might have. It was part museum, part catering hall, and of course part official events venue. It truly is the “People’s House.” You get the sense that no president can ever think that once the guests are gone these rooms will feel homey when he’s alone.

After about an hour of exploring and socializing we were ushered into the East Room for the ceremony. I sat about four rows behind the eight Medal of Honor recipients in the first row. Once we were all settled in the President was announced, we all stood, and the band struck ‘Ruffles and Flourishes’ followed by ‘Hail to the Chief’. Dave followed the President.

I thought President Trump to be a very adept master of ceremonies. His sincerity, humor, and timing were on full display. After he was awarded the medal, Dave asked if his squad members and Gold Star families could join him on the stage. It was a departure from protocol, but the President sensed the audience and the moment and ushered them all to join him. It was a very special act that embodied Dave’s relationship with the men he fought with, and it would be articulated in the speech he would give the next day.

I thought President Trump to be a very adept master of ceremonies. His sincerity, humor, and timing were on full display. After he was awarded the medal, Dave asked if his squad members and Gold Star families could join him on the stage. It was a departure from protocol, but the President sensed the audience and the moment and ushered them all to join him. It was a very special act that embodied Dave’s relationship with the men he fought with, and it would be articulated in the speech he would give the next day.

A reception followed. I was able to have a couple of pictures with Dave, chat with Michael Caputo of Buffalo, a Trump campaign advisor who found himself ensnared by the Mueller investigation. I asked him if he thought there would be any resolution that would please Trump supporters. He shrugged and said “Your guess is as good as mine.” After about a three-hour sojourn in the East Wing we returned to our buses and our police escort. Once inside the hotel lobby I could see the members of our police escort taking pictures with Dave and his family.

I had a full day and decided to skip a party that evening. I was wearing shoes for the first time after foot surgery in May, and ice packs were in order. Besides, there was Dave’s induction into the Hall of Heroes at the Pentagon the next day.

On Wednesday, we gathered in the lobby one more time for our trip to the Pentagon. We were all checked before boarding the bus, but a few layers of security were removed at our destination. The police escort led the way. The trip was much shorter, and the Pentagon is nothing to write home about. Just imagine the hallways of a school constructed in the 1970s and you’ll get the picture.

.jpg)

There was a twenty-minute ceremony inducting Dave into the Hall of Heroes. A sergeant from the Old Guard carried out the unveiling of the plaque and the presentation of the Medal of Honor flag with the same precision that is on display at the Tomb of the Unknown. After the introductory remarks given by the hosting officials, Dave delivered his speech. My hunch is that they expected perfunctory boilerplate thanking comrades, family, and the good old USA for our bountiful gifts. After all, the medal is awarded for valor in combat not for speaking skills.

What they got instead was a tour de force that placed his Iraq war alongside the other wars America has fought going back to the Revolution. It articulated the role of the citizen soldier where dissent is always part of the landscape. He elaborated on the skill, courage, and cooperation that his fellow soldiers displayed alongside him and why his medal embodied the Army’s recognition of what a fighting force was about.

Read more in New English Review:

• An Open Letter to the Democratic Presidential Candidates

• Dead Zones

• Reminiscences from the Music Scene in LA in the Early Eighties

This was no “win one for the Gipper” speech. It was an articulation of genuine American nationalism that has gone unheard for a long time because a hostile culture molded by a media establishment that abjures this message has by and large successfully silenced it. It was neither nativist or jingoistic, and that’s what made it so special . . . plus Dave’s delivery.

Back Home

The next day, when I was on the shuttle to the airport, I struck up a conversation with the other passenger, an officer dressed in his fatigues. It turns out that is was Dave’s chaplain in Iraq. He told me he never expected to attend the ceremony, but Dave got in touch with him and insisted that he participate. We spoke about the speech, and he told me was going to show it to his troops.

Once it went up on the internet I sent it to all my friends. They reacted the same way I did. So too the New York Post. On June 28th, they ran an editorial referencing the speech while urging him to run for Congress. I spoke with Dave about the editorial and the speech. It seems that the Secretary of the Army ordered all drill sergeants and recruiting sergeants to watch the speech along with troops being deployed overseas. I was told that it had about 1.5 million hits on the Pentagon website.

I was back in New York where dumping buckets of water on the heads of cops has become the new thing. Meanwhile, Dave has been touring the country for the Army getting a very different message from the people he’s been meeting and talking to. Despite the cacophony created by Colin Kaepernick’s rejection of Nike’s Betsy Ross flag design sneaker, the future of America rests with the Dave Bellavias of this country, not him.

Watch David Bellavia’s speech.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

______________________________

Marc Epstein is the author of ‘The Historians and the Geneva Naval Conference’ in Arms Limitation And Disarmament: Restraints On War, 1899-1939, edited B.J.C. McKercher, Praeger 1992. He has a PhD in Japanese diplomatic history, specializing in naval disarmament in the interwar years. His articles have appeared in Education Next, The American Educator, City Journal, the Washington Post, New York Post, and New York Sun.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link