By Guido Mina di Sospiro (August 2019)

Musik, Gustav Klimt, 1895

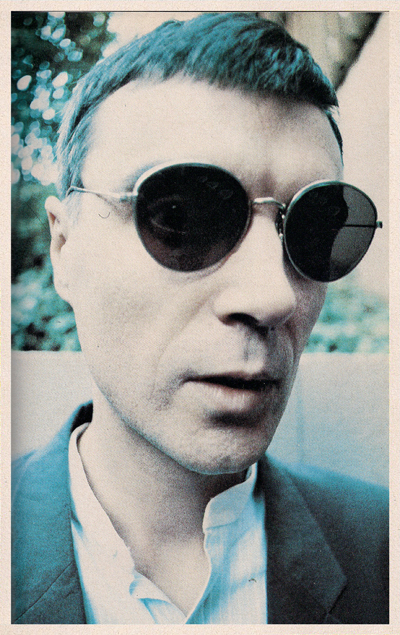

A few years ago I published The Forbidden Book, a novel co-written with Joscelyn Godwin, the noted scholar of western esotericism. Before publication, when our publisher was looking for blurbs, the name of Gary Lachman came up, himself a distinguished author in the field. He read the book and wrote a wonderful blurb. Then I noticed on Google that he went under another name, too: Gary Valentine, which opened the floodgates of memory. The Gary Valentine? The bass player for Blondie? We used to know and frequent each other in LA in what must be, for both of us, another life. I wrote to him to thank him for his blurb and refresh our friendship; he replied, “Dear Guido, my God it’s a small world! Yes, I remember meeting you and Stenie a few times back in the early 80’s with Lisa. You both dressed very well, I recall… ”

Stenie Gunn, then my girlfriend, now my wife, was the reason why I found myself in the midst of the punk/new wave scene in Los Angeles in the early Eighties. Although very young, she’d been intensely involved in music in her native New York, and of course was a regular at CBGB’s. When she moved to LA to attend UCLA, she still kept up with music. In fact her qualifications—she had had two successful college radio shows back East and had written for National RockStar, the English weekly newspaper—got us a gig with one of Italy’s best music and film magazines, the monthly Tutti Frutti, from Rome. We became their LA correspondents, and at times provided them with all the material they needed for the whole issue, texts (interviews, reviews, features, columns, news) and photos (our own and the ones given to us by record labels, as slides). In the pre-computer days, we relied on mail, notoriously terrible in Italy. In the hope of speeding things up, Tutti Frutti got a P.O. Box in the Vatican, which has its own mail (but I wonder, its own mail planes? Or did it rely on miracles?).

Back in Europe, after being immersed in it too intensely and for too long, I had overdosed on “high culture,” which eventually had led me (and the world) to the aleatory, abstract (non-)music of, among many others, Karlheinz Stockhausen and John Cage. As therapy against a surfeit of intellectualism, I was hungering for the exact opposite and the hardcore punk and New Wave scene in LA offered just that. I enjoyed the directness and crispness of that music, its raw energy, intensity and concision. Short, fast and snappy—and making a point, finally.

Read more in New English Review:

• The Upstairs/Downstairs Dilemma

• David Bellavia Steps Up Again: A Medal and a Speech

• Branding: Fascist, ‘Folks,’ and Stalinoids

The more memorable venue for punk concerts back then was Madam Wong’s. Esther Wong, the club owner, became somewhat of a legend. A no-nonsense businesswoman, she owned a restaurant in Chinatown that used to feature Polynesian bands, of all things, but didn’t attract a lot of aficionados. In 1978 she tried her luck with rock concerts, and it was an instant success. We saw there Black Flag, X, The Dead Kennedys, Circle Jerks and many more. But the music scene in LA was very eclectic, and the music industry had just been reenergized by a novelty: MTV, and the music videos it showed all day long. We were the first ones in the world to publish a feature about it. It seemed clear to us that this new medium was going to give a new lease of life to rock music.

Even as we lived through it we sensed that we were in the Silver Age of Rock, and that the Golden Age was already behind us. As for the difference between the Golden and Silver Age, it can easily be summed up to this: instead of eagerly anticipating the new LP by Led Zeppelin, or The Who, or Pink Floyd, or young David Bowie, we were now waiting for the new LP (or CD, for those who bought them) by The Talking Heads (David Byrne, R), or The Ramones, or the B-52’s, or sold out David Bowie. It bore no comparison, but even then we realized that it was still a good time for music. Why? Because there was a lot of money behind it. In his autobiography, Bill Bruford (the former drummer of Yes and King Crimson) explains how the music industry of the late Sixties and early Seventies in London reminded him of the dot-com craze of the late Nineties in America. Everybody wanted to invest in music, and very many investors did, which explains why so many bands were signed so quickly and so many genres were invented. The early Eighties got a boost from MTV, as mentioned, and from the experience that record labels had acquired in the meantime. Independent labels, like Sire Records, would make alliances with major ones to improve their distribution; there were larger and better in-house publicity departments; ever more college and/or commercial radios; more specialized press for all tastes; merchandise was beginning to be sold at concerts—and kids kept spending their money on LP’s. There were no technological distractions: no smart phones or Internet; the first rudimental PC’s were for dorks and the same went for early video games, which were played in arcades. Music was still the thing kids wanted/needed the most.

Even as we lived through it we sensed that we were in the Silver Age of Rock, and that the Golden Age was already behind us. As for the difference between the Golden and Silver Age, it can easily be summed up to this: instead of eagerly anticipating the new LP by Led Zeppelin, or The Who, or Pink Floyd, or young David Bowie, we were now waiting for the new LP (or CD, for those who bought them) by The Talking Heads (David Byrne, R), or The Ramones, or the B-52’s, or sold out David Bowie. It bore no comparison, but even then we realized that it was still a good time for music. Why? Because there was a lot of money behind it. In his autobiography, Bill Bruford (the former drummer of Yes and King Crimson) explains how the music industry of the late Sixties and early Seventies in London reminded him of the dot-com craze of the late Nineties in America. Everybody wanted to invest in music, and very many investors did, which explains why so many bands were signed so quickly and so many genres were invented. The early Eighties got a boost from MTV, as mentioned, and from the experience that record labels had acquired in the meantime. Independent labels, like Sire Records, would make alliances with major ones to improve their distribution; there were larger and better in-house publicity departments; ever more college and/or commercial radios; more specialized press for all tastes; merchandise was beginning to be sold at concerts—and kids kept spending their money on LP’s. There were no technological distractions: no smart phones or Internet; the first rudimental PC’s were for dorks and the same went for early video games, which were played in arcades. Music was still the thing kids wanted/needed the most.

We lived at walking distance from the Sunset Strip. You could walk from a huge Tower Records store (now defunct) to the Roxy and then to the Whisky a Go Go. The list of the groups that we saw in these two small clubs is sensational, from The Police to Fred Frith’s Massacre, from X to The Replacements to the greatest local New Wave band that should always have made it big but never did: The Plimsouls (but their leader Peter Case has blossomed into a minstrel and is still active). Publicity departments began to like us—and Tutti Frutti, of which we would give them issues featuring their artists—so they kept inviting us to concerts and asking us to interview their acts, big and small. The label I.R.S. introduced us to a new band which was, according to their A&R man (“A&R” stands for Artists and Repertoire) “Weird, but weird good”—R.E.M. We were hooked up for an interview with Mark Mothersbaugh, from Devo. He had just begun composing soundtracks for films and the legendary producer Dino De Laurentiis had commissioned one. While Mark wanted to give him electronics, Dino wanted, “Violins, violins, passion!”

Our publisher from Rome, one of the greatest experts on Frank Zappa and a dear friend of his, told us to go interview him at his studio, the legendary Utility Muffin Research Kitchen (UMRK), at his estate off of Laurel Canyon, and forewarned us: “Remember what Frank says: ‘Most rock journalism is people who can’t write, interviewing people who can’t talk, for people who can’t read.’”

Frank Zappa turned out to cordial, and highly opinionated, but with good reason: it was apparent to us that we were sitting across from what my USC professor from India would have called “a higher level of consciousness.” He was then composing formal music, and we knew that he was equally at home with Pierre Schaeffer’s musique concrète as with Pachuco music. We also knew of his vis polemica, and stoked it with the question, “Do you think people in the music business really love music?” He replied,  incensed: “Absolutely not! I’ve never seen anybody in an executive position in a record company who gave a fuck about music. They all hate music, and worse than that they hate the people who make the music. No matter what they tell you or how they treat you at a party, they hate you!”

incensed: “Absolutely not! I’ve never seen anybody in an executive position in a record company who gave a fuck about music. They all hate music, and worse than that they hate the people who make the music. No matter what they tell you or how they treat you at a party, they hate you!”

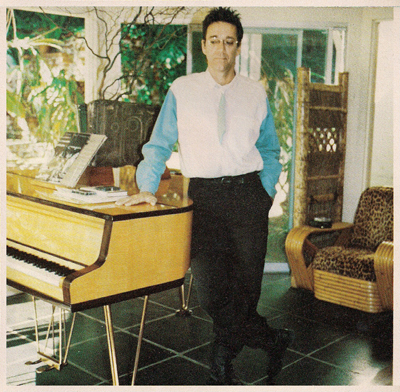

Ray Manzarek (R), of The Doors, welcomed us to his home in the Hollywood Hills, with a beautiful blonde piano in the living room. He was working on a solo album of Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana. While I don’t remember the content of the interview with him (though I could easily dig it up, having kept the all Tutti Frutti issues), I do remember something else: he welcomed us to his home with grace. Someone who had been at the heart of Rock’s Golden Age was now taking these young pups under his wing and talking to them about the good old days, but not at all in a patronizing way. The warmth and wisdom of his deportment have stayed with me all these years. I remember Paul Westerberg, of The Replacements, fuming right after an awkward interview with some French journalist; but Stenie made him feel at ease, and got a very interesting conversation going. He was not only a brilliant songwriter but a charming man. His band, of all the ones we heard then and since, has another distinction—it was by far the loudest! We were asked  to interview the lead singer of a brand new group: Anthony Kiedis (R), of The Red Hot Chili Peppers. When Stenie mentioned that she owned an old Alfa Romeo Duetto, he got so excited that he wanted to take a look at it and for her to take a picture of his sitting at its wheel. And the list goes on and on.

to interview the lead singer of a brand new group: Anthony Kiedis (R), of The Red Hot Chili Peppers. When Stenie mentioned that she owned an old Alfa Romeo Duetto, he got so excited that he wanted to take a look at it and for her to take a picture of his sitting at its wheel. And the list goes on and on.

An aspect of those days was the lack of information. In the pre-Internet age, info was hard to come by. We, as insiders, could ring up people at the various publicity departments as well as A&R men and women to find out what so-and-so was up to, but the regular record-buyer had to rely on what the clerk at Tower Records would tell them, or their friends, or music magazines. There was a lot of hearsay, and plenty of misinformation. The LA music scene went from neopsychedelic to metal, both hair and not; from punk and New Wave to girl groups and everything in between. The unofficial high priest officiating over it all was Rodney Bingenheimer, a radio deejay who had a knack for discovering and then promoting “edgy new bands.” His intuition was almost uncannily infallible, and in an age of disproportionate earnings for so many involved in the music industry he represents an exception. A soft-spoken, sweet-natured man, it seems to us that he promoted music for the sake of music itself rather than for personal advancement.

We received promotional albums daily; in their inner sleeves were photos of the artists; their bios; clips from the press—a whole package. Many music journalists took the promo albums they didn’t care for to record stores for quick cash, but we never did. And that’s why, going through our collection now, and finding the LP’s filled with (excessive) promotional material, we look back and think of a period of opulence. We were eventually invited to the after-concert parties, too. If record labels wanted us to interview some new act, to entice us they’d send a chauffeur to pick us up. Kids were buying records by the millions, and Duran Duran were causing the same mass hysteria of the Beatles. Touring then was a money-losing proposition, but bands did it anyway to support their albums, whose sales were the money-makers. Nowadays, it’s exactly the opposite, as even legendary producer and sonic visionaire Brian Eno has recently remarked.

Read more in New English Review:

• Defending the Indefensible: Why Holocaust Denial Should be Legal

• Trippin’ with Tim

• Rag & Bone

We interviewed David Lee Roth, the lead singer from Van Halen, shortly before the release of “1984,” their greatest commercial success which went on to sell 12 million copies in the US alone. Not exactly our cup of tea, as both Stenie and I much preferred offerings from the New Wave, but a lot of fun anyway: a bigger-than-life character, hyperactive, hilarious and genuinely personable. He liked us and invited us to their general rehearsal before they went on tour. They had rented a huge warehouse; in attendance were a few fellow members of the press, and hundreds upon hundreds of groupies dressed to kill. There was no way that somebody like David Lee Roth would sit as judge in a televised singing contest; that would have been simply inconceivable.

It seems another lifetime: the record industry—created by technology, with FM radios, LP’s and hi-fi, and then boosted by MTV and music videos—has now succumbed to technology. But more than that, the energy seems to have migrated elsewhere. Troubadours of global reach and consequence are now gone; music no longer dominates the life of young people—it’s smartphones and tablets and videogames. The (perhaps disproportionate) excitement is not in music any longer, but elsewhere. And yet, in a way, those three-minute songs of the 1980s were perhaps the precursors to the social media of today. For sure, without them, youth would never have developed such a strong sense of its own identity as distinct from its parents. And now, there is no need for the music in the same way, because all sorts of other stuff that exists in all those electronic and virtual formats would seem to do the same job.

There may well also be intrinsic reasons: the number of things that can be done with the same instruments and chords is great, but not infinite, and one has the impression of having heard it all before. Post-rock has shown the way to a nonrock use of traditional rock instruments, but contemporary creative (i.e., non-derivative) music is a lively but marginal niche market. Great periods do come to an end. It’s happened to, say, church-building; and to sculpture, and painting. Think of the Vienna of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert and many more composers and musicians—nothing of that artistic magnitude has happened since.

Madame Wong’s downtown closed up in 1985, and Madame Wong’s West in Santa Monica, in 1991. The “godmother of punk” had realized that music trends had changed, and that kids were no longer living on burgers and music. In 1988, on the other side of the Atlantic, a synth-pop group that had been called the poor person’s Duran Duran, Talk Talk, committed commercial suicide by recording Spirit of Eden, which in retrospect many see as the first album of post-rock, or at least proto-post-rock. And in my view, that’s just about when rock ceased to be young and innovative. But in fairness, the period between, say, Buddy Holly’s That’ll Be The Day, released in 1957, and 1988 must be considered a very good run—31 years. Despite its many incarnations, rock music could not realistically hope to remain forever young.

All photos by Stenie Mina di Sospiro.

«Previous Article Home Page Next Article»

__________________________________

Guido Mina di Sospiro was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, into an ancient Italian family. He was raised in Milan, Italy and was educated at the University of Pavia as well as the USC School of Cinema-Television, now known as USC School of Cinematic Arts. He has been living in the United States since the 1980s, currently near Washington, D.C. He is the author of several books including, The Story of Yew, The Forbidden Book, and The Metaphysics of Ping Pong.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast